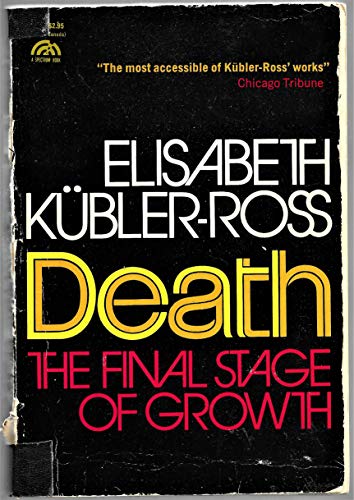

Death: The Final Stage of Growth (Human Development Books) - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Why Is It So Hard to Die?

Dying is an integral part of life, as natural and predictable as being born. But whereas birth is cause for celebration, death has become a dreaded and unspeakable issue to be avoided by every means possible in our modern society. Perhaps it is that death reminds us of our human vulnerability in spite of all our technological advances. We may be able to delay it, but we cannot escape it. We, no less than other, nonrational animals, are destined to die at the end of our lives. And death strikes indiscriminately -- it cares not at all for the status or position of the ones it chooses; everyone must die, whether rich or poor, famous or unknown. Even good deeds will not excuse their doers from the sentence of death; the good die as often as the bad. It is perhaps this inevitable and unpredictable quality that makes death so frightening to many people. Especially those who put a high value on being in control of their own existence are offended by the thought that they, too, are subject to the forces of death.

But other societies have learned to cope better with the reality of death than we seem to have done. It is unlikely that any group has ever welcomed death's intrusion on life, but there are others who have successfully integrated the expectation of death into their understanding of life. Why is it so hard for us to do this? The answer may lie in the question. It is difficult to accept death in this society because it is unfamiliar. In spite of the fact that it happens all the time, we never see it. When a person dies in a hospital, he is quickly whisked away; a magical disappearing act does away with the evidence before it could upset anyone. But, as you will read later in various contexts, being part of the dying process, the death, and the burial, including seeing and perhaps interacting with the body, is an important part of coming to grips with death -- that of the person who has died and your own.

We routinely shelter children from death and dying, thinking we are protecting them from harm. But it is clear that we do them a disservice by depriving them of the experience. By making death and dying a taboo subject and keeping children away from people who are dying or who have died, we create fear that need not be there. When a person dies, we "help" their loved ones by doing things for them, being cheerful, and fixing up the body so it looks "natural." Again, our "help" is not helpful; it is destructive. When someone dies, it is important that those close to him participate in the process; it will help them in their grief, and it will help them face their own death more easily.

It is hard to die, and it will always be so, even when we have learned to accept death as an integral part of life, because dying means giving up life on this earth. But if we can learn to view death from a different perspective, to reintroduce it into our lives so that it comes not as a dreaded stranger but as an expected companion to our life, then we can also learn to live our lives with meaning -- with full appreciation of our finiteness, of the limits on our time here. I hope that this book will help you understand death and dying better and will make it a little less hard for you to die and a little easier for you to live.

Most people in our society die in a hospital. This, in itself, is one of the primary reasons that dying is so hard. The first selection of this chapter explores, from a sociological point of view, the hospital ?as a depersonalizing institution which is not, by definition, set up to meet the human needs of people whose physiological condition is beyond the hospital's capability for successful intervention; these patients represent a failure of the institution in its life-sustaining role, and there is nothing in the system that provides for human nurturance to the soul when the body is beyond repair. The other selection is a moving poem by a young student-nurse who is dying. Having spent time in the hospital as a practitioner and now as a patient, she issues a plea to those who minister to the sick and dying to step away from their professional roles and reach out as human beings to those who need them.

The Organizational Context of Dying

Hans O. Mauksch, Ph.D.

In our modern technological society, dying is something you do in a hospital. But hospitals art efficient, impersonalized institutions where it is very difficult to live with dignity -- where there is no time and place in the routine to deal with the human needs of sick human beings. In the following selection, Dr. Mauksch explains why it is that hospitals, by definition, are rarely responsive to the special needs of people who are dying. Hospitals are institutions committed to the healing process, and dying patients are a threat to that defined role. The professionals in hospitals have specified expectations and routines to carry out; these simply don't these simply don't work with dying patients. This is a threat to the professionals' roles and creates feelings of inadequacy which are inconsistent with their defines roles as people who can deal effectively with disease. There is no room in the prescribed roles of professionals for them to behave as human beings in response to their dying patients. The history and reasons for the kinds of constraints that exist in the hospital organization are explored by Dr. Mauksch, and he proposes that this need not be so. I think you will find this perspective on the hospital setting (for all people, whether they are dying or not) a very valuable one.

The predominant number of deaths these days occur within the hospital, the institution created by society to support the healing services. Actually, to be historically correct, there was a period in the early phases of the development of this institution when the hospital, indeed, was the institution for people who were either poor and indigent or who were dying. As the science and technology of medicine and of the other health professions have experienced the dramatic growth and development which characterizes the health field in the twentieth century, the whole flavor, aura, culture, and social organization of the hospital has shifted from an institution devoted to charity and to those who die to an institution which is fundamentally committed to healing, to curing, to restoring, and to the recovery process.

In a differentiated society like our modern, highly complex one, we tend to endow the occupants of social roles and institutions with mandates which denotate their purpose, their function, and their values. The current roles of the health professions have emerged through their own achievements and through the growth of social expectations. In the midst of the current technological emphasis on the success story of healing, the patient whose disease cannot be cured, the human being who is dying is inexorably perceived to be a failure to the health professions -- a failure of the mandate given to the professionals and to the institutions. The organizational context of dying within the hospital must be understood as an institutional response to an event which today is identified as a failure, although it also remains a reminder of the limits of medical knowledge and capabilities.

A second, more subtle dimension of the organizational context of dying is the different focus required by the needs of the dying patient compared to the needs of the patient whose illness is about to be cured. As a social scientist within the medical setting, I seek to remind physicians and other health professionals that the human being who happens to be ill is indeed an integral part of the disease process and that his or her interactions are crucial to the cure, the care, and the future life of the patient. In the case of the dying patient, the current culture of the hospital, which emphasizes the disease process and the diseased organ, is counterproductive to the needs of the dying patient. Dying is a total experience, and at the point of dying, the diseased organ ceases to be the primary issue.

There is a third dimension to the climate of dying. In his book Passing On: The Social Organization of Dying, David Sudnow suggests that physicians and nurses, in their behavior and in their attitudes, demonstrate a sense of discomfort and a sense of guilt when facing human beings who, entrusted to their care, terminate their lives in the face of all efforts. Those of us who are committed to recovery, to healing, to cure cannot avoid, within the context of the hospital culture, sensing that we have failed when one of our patients dies. There are several ways in which this sense of guilt, this sense of failure can be understood. It suggests the search for whether everything had been done, whether there were other kinds of resources that could have been invoked, whether all diagnostic and therapeutic means had been employed.

There is a second way in which one can look at this particular issue. There is a mixture of reality and myth in the belief in the continuous growth and expansion of medical knowledge. I have interviewed a number of physicians who, in the face of the death of a patient, raised the question, "Is there someone else, somewhere, who has new knowledge that could have made the difference?" The sense in which every physician feels responsible for the total state of current medical knowledge apparently varies from physician to physician and hospital setting to hospital setting, but it is an important potential cause for the discomfort of the physician and for possible blocks in the relationship between physician and patient.

There is the third haunting possibility that I, the physician, or I, the nurse, may have made a mistake, may have committed an error which contributed to the patient's death. Somewhere within the hospital culture lurks the awesome expectation that, while all other human beings are permitted to make mistakes and to commit errors, physician's and nurses must not. Indeed, the facts suggest that these clouds of possible errors have only limit...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPrentice Hall Press

- Publication date1975

- ISBN 10 0131969986

- ISBN 13 9780131969988

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages181

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Death: The Final Stage of Growth (Human Development Books)

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0131969986xvz189zvxnew

Death: The Final Stage of Growth (Human Development Books)

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0131969986-new

Death: The Final Stage of Growth (Human Development Books)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0131969986

Death: The Final Stage of Growth (Human Development Books)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0131969986

Death: The Final Stage of Growth (Human Development Books)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0131969986

DEATH: THE FINAL STAGE OF GROWTH

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.45. Seller Inventory # Q-0131969986