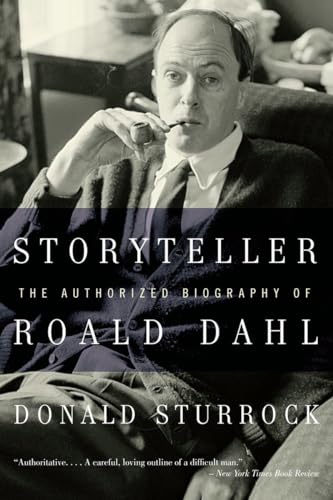

Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl - Softcover

Anyone who ever wished as a child to meet Willy Wonka or hang out with the BFG will be fascinated to learn in this engrossing, authorized biography of the late Roald Dahl that his own life was far, far more strange than even his fiction.

Twenty years after his death, Roald Dahl's bestselling stories continue to inspire and entertain children around the globe. But the man behind the stories remains an enigma. Despite his astonishing life as a Norwegian growing up in Wales, whose father died when he was just five, and as an ace fighter pilot, British intelligence agent, and husband for a while to one of Hollywood's top stars, Dahl nonetheless persistently embroidered the truth about himself, rewrote history, ignored reality, and defended his deep vulnerabilities with outlandish and wilfully provocative remarks. Facts bored him.

As his authorized biographer, Donald Sturrock, a wonderful writer and careful researcher, has drawn on Dahl's many previously unexamined files and a vast body of unpublished letters for this nuanced and engrossing narrative of the storyteller's long, adventurous life.

From the Hardcover edition.

Twenty years after his death, Roald Dahl's bestselling stories continue to inspire and entertain children around the globe. But the man behind the stories remains an enigma. Despite his astonishing life as a Norwegian growing up in Wales, whose father died when he was just five, and as an ace fighter pilot, British intelligence agent, and husband for a while to one of Hollywood's top stars, Dahl nonetheless persistently embroidered the truth about himself, rewrote history, ignored reality, and defended his deep vulnerabilities with outlandish and wilfully provocative remarks. Facts bored him.

As his authorized biographer, Donald Sturrock, a wonderful writer and careful researcher, has drawn on Dahl's many previously unexamined files and a vast body of unpublished letters for this nuanced and engrossing narrative of the storyteller's long, adventurous life.

From the Hardcover edition.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

DONALD STURROCK is an award-winning TV film producer and a librettist who has been the artistic director of the Roald Dahl Foundation since 1992. He grew up in England and South America, attended Oxford University, and joined BBC Television's Music and Arts Department in 1983. In 1995 Sturrock directed an acclaimed BBC television version of his own adaptation of Roald Dahl's Little Red Riding Hood with Danny DeVito, Ian Holm, and Julie Walters. In 1998, at the Los Angeles Opera, Sturrock also directed the world premiere of Fantastic Mr. Fox, an opera based on Dahl's book, adapted by Sturrock, and with designs by Gerald Scarfe. His children's opera Keepers of the Night premiered in Los Angeles in 2007. Storyteller is his first book.

From the Hardcover edition.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

From the Hardcover edition.

CHAPTER ONE

The Outsider

IN JULY 1822, The Gentleman’s Magazine of Parliament Street, Westminster, reported a terrible accident. Its correspondent described how a few weeks earlier, in the tiny Norwegian hamlet of Grue, close to the border with Sweden, the local church had burned down. It was Whit Sunday and the building was packed with worshippers. As the young pastor warmed to the themes of his Pentecostal sermon, the aged sexton, tucked away in an unseen corner under the gallery, had felt his eyelids becoming heavy. By his side, in a shallow grate, glowed the fire he used for lighting the church candles. Gently its warmth spread over him and very soon he was fast asleep. Before long, a smell of burning was drifting through the airless building. The congregation stirred, but obediently remained seated as the priest continued to explain why the Holy Spirit had appeared to Christ’s apostles as countless tongues of fire. The smell got stronger. Smoke started to drift into one of the aisles. The sexton meanwhile snoozed on oblivious. By the time he awoke, an entire wall of the ancient church was ablaze. He ran out into the congregation, shouting at the worshippers to save themselves. Suffocating in the thick smoke, they pressed against the church’s sturdy wooden doors in a desperate attempt to escape the flames. But the doors opened inwards and the pressure of the terrified crowd simply forced them ever more tightly shut. Within ten minutes, the entire church, which was constructed almost entirely out of wood and pine tar, became an inferno. That day over one hundred people met, as the magazine described it, “a most melancholy end,” burning to death in what is still the most catastrophic fire in Norwegian history.

Only a few people survived. They did so by following the example of their preacher. For Pastor Iver Hesselberg did not join the rush toward the closed church doors. Instead, he jumped swiftly down from his pulpit and, with great practical purpose, began piling up Bibles under one of the high windows by the altar. Then, after scrambling up them to the relative security of the window ledge, he hurled himself through the leaded glass and out of the burning edifice to safety. Some might have called his actions selfish, but all over Europe newspapers praised the cool logic of the enterprising priest, who thought his way out of a crisis and did not succumb to the group stampede. Here was a man of his time, they wrote, a thinker: an individual who stood outside his flock. Grateful for his second chance in life, Pastor Hesselberg evolved into a philanthropist and public figure. A contemporary remembered him as “a strict man who preached fine sermons,” a staunch Lutheran who was also a liberal idealist, visiting the poor and teaching them arithmetic, as well as how to read and write. He even founded a parish library.

Hesselberg ended his days as a distinguished theologian and eventually a member of the Norwegian parliament, where he helped to ensure that all public buildings in Norway would in future be built with doors that opened outwards. His son, Hans Theodor, attempted to follow in his footsteps. He trained for the priesthood and married into one of Norway’s most distinguished families. His wife was a descendant of Peter Wessel, a Norwegian naval hero, who had been killed in a duel in 1720. They settled at Vaernes,* a large farm not far from Trondheim, the ancient capital of Norway, whose magnificent Romanesque cathedral, built on the shrine of Norway’s patron saint, St. Olave, almost a millennium ago, evokes a virtually forgotten age when Scandinavia was a key spiritual center of Christian Europe.

*Most of the Vaernes farmlands have now been subsumed into Trondheim Airport, but the actual building Hans Theodor owned is still standing. He is buried nearby in the cemetery of Vaernes Church.

In Vaernes, Hans Theodor raised eleven children, but he lacked his father’s shrewd judgment and talent for hard work. He drank excessively, managed his estates incompetently, and never practiced as a priest. He was also an incorrigible—and unsuccessful—gambler. Bit by bit, he was forced to sell off his lands to pay his gaming debts. One evening he went too far. He staked the village storehouse in a game of cards and lost. Outraged at this disregard for his responsibilities to his flock, the local community forced him to sell what remained of the farm. Hans Theodor moved to Trondheim, where he died a pauper in 1898. But his children went out into the world and prospered—many entering the burgeoning Norwegian middle classes. Two became merchants, one became an apothecary, another a meteorologist. Yet another, Karl Laurits, trained as a scientist, then studied law and eventually went to work in Christiania, now Oslo, as an administrator in the Norwegian Public Service Pension Fund. In 1884 he married Ellen Wallace, and the following year, his first daughter, Sofie Magdalene, was born in Kristiania.* Thirty-one years later, on a crisp autumn day in South Wales, she would give birth to her only son, Roald.

*Confusingly, the capital of Norway has undergone several changes of name. Ancient Norse Oslo was renamed Christiania in 1624 after King Christian IV of Norway rebuilt it following a disastrous fire. In 1878, Christiania was refashioned as Kristiania, and in 1925, the city became Oslo once again.

Roald Dahl himself was not that interested in his ancestry or in historical detail. Though proud of his Norwegian roots, archives and public records were not his domain, and when, in his late sixties, he wrote his own two volumes of memoirs, Boy and Going Solo, he seems to have known nothing of his great-great-grandfather Hesselberg’s extraordinary escape from the church fire or of the streak of reckless gambling and alcohol addiction that had emerged in his descendants. Yet Pastor Hesselberg’s story would almost certainly have fascinated Roald. He would have admired his ancestor’s resourceful ingenuity, as well as his ability to think both laterally and practically in the face of a crisis. These were qualities he admired in others and they were attributes he gave to the heroes and heroines of many of his children’s books. In his own life, too, Dahl would face many moments of crisis and struggle, and seldom were his resources of tenacity or inventiveness found wanting. His psychology and philosophy was always positive. “Get on with it,” was one of his favorite phrases, recommended to family, friends and colleagues alike, and one that he put into practice many times in his life when dealing with adversity—whether that was accident, war, injury, illness, depression or death. Like Pastor Hesselberg, he seldom looked behind him. He infinitely preferred to look forward.

Yet this was only one side of the man. His daughter Ophelia once described her father to me as “a pessimist by nature,” and a depressive streak ran through both sides of his family. Many of his adult stories revealed a jaundiced and sometimes bleak view of human behavior, which drew repeatedly on man’s capacity for cruelty and insensitivity. His children’s writing is sunnier, more positive—though even there, early critics complained of tastelessness and brutality. It was a charge against which he always energetically defended himself, for underneath the exterior of the humorist and entertainer lurked a fierce moralist. But he found it hard because, like many writers, he hated analyzing his own writing. I remember asking him on camera why so many of the central characters in his children’s stories had lost one or both parents. He was taken aback by the question and at first even denied that this was the case. However, when, on reflection, he realized that he had made a mistake, his brain searched swiftly for a way out. He compared himself to Dickens. He had used “a trick,” he said, “to get the reader’s sympathy.” In a rare confession of error, he admitted with a smile that he “had been caught out a bit.” What struck me most profoundly was that he seemed to make no conscious connection between his own life—he had lost his own father when he was three years old—and the worlds he created in his stories. It suggested, I thought, a kind of unexpected innocence and naïveté.

Dahl’s writing career would take many twists and turns over the course of his seventy-four years, and these convolutions were intimately bound up with a complex private life that held many hidden corners, secrets and anxieties. Together they made a powerful cocktail—for Dahl was full of contradictions and paradoxes. He loved the privacy of his writing hut, yet he liked to be in the public eye. He described himself as a family man, living in a modest English village, yet he was married to an Oscar-winning movie star, and kept the company of presidents and politicians, diplomats and spies. He was fascinated by wealth and glamour. He often bragged. He gambled. He had a quick and discerning eye for great art and craftsmanship. He was drawn to the good things in life. Yet he was also a simple man, who preferred the Buckinghamshire countryside to life in the city—a man who grew fruit, vegetables and orchids with obsessive passion, who surrounded himself with animals, who bred and raced greyhounds, and who kept the company of tradesmen and artisans. He was generous, although his kindness was usually quiet and low key. Often only the recipient was aware of it. Roald himself, however, was no shrinking violet. He enjoyed public appearances, and delighted in being controversial. He was a conundrum. An egotistical self-publicist—notoriously brash, even oafish, in the limelight—he could also behave as slyly as the foxes he so admired. If he wanted, he could cover his tracks and go to ground.

As a writer, he was the most unreliable of witnesses—particularly when he spoke or wrote about himself. In Boy, his own evocative and zestful memoir of childhood, he begins by disparaging most autobiography as “full of all sorts of boring details.” His book, he asserts, will be no history, but a series of memorable impressions, simply skimmed off the top of his consciousness and set down on paper. These vignettes of childhood are painted in bold colors and leap vividly off the page. They are infused with detail that is often touching, and always devoid of sentiment. Each adventure or escapade is retold with the intimate spirit of one child telling another a story in the playground. The language is simple and elegant. Humor is to the fore. Self-pity is entirely absent. “Some [incidents] are funny. Some are painful. Some are unpleasant,” he declares of his memories, concluding theatrically: “All are true.” In fact, almost all are, to some extent, fiction. The semblance of veracity is achieved by Dahl’s acute observational eye, which adds authenticity to the most fantastical of tales, and by a remarkable trove of 906 letters he kept at his side as he wrote. These were letters he had written to his mother throughout his life, and which she hoarded carefully, preserving them through the storms of war and countless changes of address.

In these miniature canvases, Dahl began to hone his idiosyncratic talent for interweaving truth and fiction. It would be pedantic to list the inaccuracies in Boy or its successor Going Solo. Most of them are unimportant. A grandfather confused with a great-grandfather, a date exaggerated, a slip in chronology, countless invented details. Boy is a classic, not because it is based on fact but because Dahl had a genius for storytelling. Yet its untruths, omissions and evasions are revealing. Not only do they disclose the author’s need to embellish, they hint as well at the complex hidden roots of his imagination, which lay tangled in a soil composed of lost fathers, uncertain friendships, a need to explore frontiers, an essentially misanthropic view of humanity, and a sense of fantasy that stemmed in large part from the Norwegian blood that ran powerfully through his veins.

Norway was always important to Dahl. Though he would sometimes surprise guests at dinner by maintaining garrulously that all Norwegians were boring, he never lost his profound affection for and bond with his homeland. His mother lived in Great Britain for over fifty years, yet never renounced her Norwegian nationality, even though it sometimes caused her inconvenience—most notably when she had to live as an alien in the United Kingdom during two world wars. Although she usually spoke to her children in English and always wrote to them in her adopted language, she made sure they also learned to speak Norwegian at the same time they were learning English; and every summer she took them to Norway on holiday. Forty years later, Roald would recreate these summer holidays for his own children, reliving memories that he would later immortalize in Boy. “Totally idyllic,” was how he described these vacations. “The mere mention of them used to send shivers of joy rippling all over my skin.” Part of the pleasure was, of course, an escape from the rigors of an English boarding school, but for Roald the delight was also more profound. “We all spoke Norwegian and all our relations lived over there,” he wrote in Boy. “So, in a way, going to Norway every summer was like going home.”

“Home” would always be a complex idea for him. His heart may have sometimes felt it was in Norway, but the home he dreamed about most of the time was an English one. During the Second World War, when he was in Africa and the Middle East as a pilot and in Washington as a diplomat, it was not Norway he craved for, nor the valleys of Wales he had loved as a child, but the fields of rural England. There, deep in the heart of the Buckinghamshire countryside, he, his mother and his three sisters would later construct for themselves a kind of rural enclave: the “Valley of the Dahls,” as Roald’s daughter Tessa once described it. Purchasing homes no more than a few miles away from each other, the family lived, according to one of Roald’s nieces, “unintegrated . . . and largely without proper English friends.” For though Dahl was proud to be British and though he craved recognition and acceptance from English society, for most of his life he preferred to live outside its boundaries, making his own rules and his own judgments, not unlike his ancestor, Pastor Hesselberg.

As a result, English people found him odd. His best friend at prep school admitted that he was drawn to Roald because he was “a foreigner.” And he was. Though born in Britain, and a British citizen, in many ways Dahl retained the psychology of an émigré. Later in his life, people forgot that. They interpreted his behavior through the false perspective of an assumed “Englishness,” to which he perhaps aspired, but which was never naturally his. They saw only a veneer and they misunderstood it. In truth, Roald was always an outsider, the child of Norwegian immigrants, whose native land would become for their son an imaginative refuge, a secret world he could always call his own.

As with many children of emigrants, Roald would take on the manners and identity of his adopted home with the zeal of a convert. His sister Alfhild complained that her brother did n...

The Outsider

IN JULY 1822, The Gentleman’s Magazine of Parliament Street, Westminster, reported a terrible accident. Its correspondent described how a few weeks earlier, in the tiny Norwegian hamlet of Grue, close to the border with Sweden, the local church had burned down. It was Whit Sunday and the building was packed with worshippers. As the young pastor warmed to the themes of his Pentecostal sermon, the aged sexton, tucked away in an unseen corner under the gallery, had felt his eyelids becoming heavy. By his side, in a shallow grate, glowed the fire he used for lighting the church candles. Gently its warmth spread over him and very soon he was fast asleep. Before long, a smell of burning was drifting through the airless building. The congregation stirred, but obediently remained seated as the priest continued to explain why the Holy Spirit had appeared to Christ’s apostles as countless tongues of fire. The smell got stronger. Smoke started to drift into one of the aisles. The sexton meanwhile snoozed on oblivious. By the time he awoke, an entire wall of the ancient church was ablaze. He ran out into the congregation, shouting at the worshippers to save themselves. Suffocating in the thick smoke, they pressed against the church’s sturdy wooden doors in a desperate attempt to escape the flames. But the doors opened inwards and the pressure of the terrified crowd simply forced them ever more tightly shut. Within ten minutes, the entire church, which was constructed almost entirely out of wood and pine tar, became an inferno. That day over one hundred people met, as the magazine described it, “a most melancholy end,” burning to death in what is still the most catastrophic fire in Norwegian history.

Only a few people survived. They did so by following the example of their preacher. For Pastor Iver Hesselberg did not join the rush toward the closed church doors. Instead, he jumped swiftly down from his pulpit and, with great practical purpose, began piling up Bibles under one of the high windows by the altar. Then, after scrambling up them to the relative security of the window ledge, he hurled himself through the leaded glass and out of the burning edifice to safety. Some might have called his actions selfish, but all over Europe newspapers praised the cool logic of the enterprising priest, who thought his way out of a crisis and did not succumb to the group stampede. Here was a man of his time, they wrote, a thinker: an individual who stood outside his flock. Grateful for his second chance in life, Pastor Hesselberg evolved into a philanthropist and public figure. A contemporary remembered him as “a strict man who preached fine sermons,” a staunch Lutheran who was also a liberal idealist, visiting the poor and teaching them arithmetic, as well as how to read and write. He even founded a parish library.

Hesselberg ended his days as a distinguished theologian and eventually a member of the Norwegian parliament, where he helped to ensure that all public buildings in Norway would in future be built with doors that opened outwards. His son, Hans Theodor, attempted to follow in his footsteps. He trained for the priesthood and married into one of Norway’s most distinguished families. His wife was a descendant of Peter Wessel, a Norwegian naval hero, who had been killed in a duel in 1720. They settled at Vaernes,* a large farm not far from Trondheim, the ancient capital of Norway, whose magnificent Romanesque cathedral, built on the shrine of Norway’s patron saint, St. Olave, almost a millennium ago, evokes a virtually forgotten age when Scandinavia was a key spiritual center of Christian Europe.

*Most of the Vaernes farmlands have now been subsumed into Trondheim Airport, but the actual building Hans Theodor owned is still standing. He is buried nearby in the cemetery of Vaernes Church.

In Vaernes, Hans Theodor raised eleven children, but he lacked his father’s shrewd judgment and talent for hard work. He drank excessively, managed his estates incompetently, and never practiced as a priest. He was also an incorrigible—and unsuccessful—gambler. Bit by bit, he was forced to sell off his lands to pay his gaming debts. One evening he went too far. He staked the village storehouse in a game of cards and lost. Outraged at this disregard for his responsibilities to his flock, the local community forced him to sell what remained of the farm. Hans Theodor moved to Trondheim, where he died a pauper in 1898. But his children went out into the world and prospered—many entering the burgeoning Norwegian middle classes. Two became merchants, one became an apothecary, another a meteorologist. Yet another, Karl Laurits, trained as a scientist, then studied law and eventually went to work in Christiania, now Oslo, as an administrator in the Norwegian Public Service Pension Fund. In 1884 he married Ellen Wallace, and the following year, his first daughter, Sofie Magdalene, was born in Kristiania.* Thirty-one years later, on a crisp autumn day in South Wales, she would give birth to her only son, Roald.

*Confusingly, the capital of Norway has undergone several changes of name. Ancient Norse Oslo was renamed Christiania in 1624 after King Christian IV of Norway rebuilt it following a disastrous fire. In 1878, Christiania was refashioned as Kristiania, and in 1925, the city became Oslo once again.

Roald Dahl himself was not that interested in his ancestry or in historical detail. Though proud of his Norwegian roots, archives and public records were not his domain, and when, in his late sixties, he wrote his own two volumes of memoirs, Boy and Going Solo, he seems to have known nothing of his great-great-grandfather Hesselberg’s extraordinary escape from the church fire or of the streak of reckless gambling and alcohol addiction that had emerged in his descendants. Yet Pastor Hesselberg’s story would almost certainly have fascinated Roald. He would have admired his ancestor’s resourceful ingenuity, as well as his ability to think both laterally and practically in the face of a crisis. These were qualities he admired in others and they were attributes he gave to the heroes and heroines of many of his children’s books. In his own life, too, Dahl would face many moments of crisis and struggle, and seldom were his resources of tenacity or inventiveness found wanting. His psychology and philosophy was always positive. “Get on with it,” was one of his favorite phrases, recommended to family, friends and colleagues alike, and one that he put into practice many times in his life when dealing with adversity—whether that was accident, war, injury, illness, depression or death. Like Pastor Hesselberg, he seldom looked behind him. He infinitely preferred to look forward.

Yet this was only one side of the man. His daughter Ophelia once described her father to me as “a pessimist by nature,” and a depressive streak ran through both sides of his family. Many of his adult stories revealed a jaundiced and sometimes bleak view of human behavior, which drew repeatedly on man’s capacity for cruelty and insensitivity. His children’s writing is sunnier, more positive—though even there, early critics complained of tastelessness and brutality. It was a charge against which he always energetically defended himself, for underneath the exterior of the humorist and entertainer lurked a fierce moralist. But he found it hard because, like many writers, he hated analyzing his own writing. I remember asking him on camera why so many of the central characters in his children’s stories had lost one or both parents. He was taken aback by the question and at first even denied that this was the case. However, when, on reflection, he realized that he had made a mistake, his brain searched swiftly for a way out. He compared himself to Dickens. He had used “a trick,” he said, “to get the reader’s sympathy.” In a rare confession of error, he admitted with a smile that he “had been caught out a bit.” What struck me most profoundly was that he seemed to make no conscious connection between his own life—he had lost his own father when he was three years old—and the worlds he created in his stories. It suggested, I thought, a kind of unexpected innocence and naïveté.

Dahl’s writing career would take many twists and turns over the course of his seventy-four years, and these convolutions were intimately bound up with a complex private life that held many hidden corners, secrets and anxieties. Together they made a powerful cocktail—for Dahl was full of contradictions and paradoxes. He loved the privacy of his writing hut, yet he liked to be in the public eye. He described himself as a family man, living in a modest English village, yet he was married to an Oscar-winning movie star, and kept the company of presidents and politicians, diplomats and spies. He was fascinated by wealth and glamour. He often bragged. He gambled. He had a quick and discerning eye for great art and craftsmanship. He was drawn to the good things in life. Yet he was also a simple man, who preferred the Buckinghamshire countryside to life in the city—a man who grew fruit, vegetables and orchids with obsessive passion, who surrounded himself with animals, who bred and raced greyhounds, and who kept the company of tradesmen and artisans. He was generous, although his kindness was usually quiet and low key. Often only the recipient was aware of it. Roald himself, however, was no shrinking violet. He enjoyed public appearances, and delighted in being controversial. He was a conundrum. An egotistical self-publicist—notoriously brash, even oafish, in the limelight—he could also behave as slyly as the foxes he so admired. If he wanted, he could cover his tracks and go to ground.

As a writer, he was the most unreliable of witnesses—particularly when he spoke or wrote about himself. In Boy, his own evocative and zestful memoir of childhood, he begins by disparaging most autobiography as “full of all sorts of boring details.” His book, he asserts, will be no history, but a series of memorable impressions, simply skimmed off the top of his consciousness and set down on paper. These vignettes of childhood are painted in bold colors and leap vividly off the page. They are infused with detail that is often touching, and always devoid of sentiment. Each adventure or escapade is retold with the intimate spirit of one child telling another a story in the playground. The language is simple and elegant. Humor is to the fore. Self-pity is entirely absent. “Some [incidents] are funny. Some are painful. Some are unpleasant,” he declares of his memories, concluding theatrically: “All are true.” In fact, almost all are, to some extent, fiction. The semblance of veracity is achieved by Dahl’s acute observational eye, which adds authenticity to the most fantastical of tales, and by a remarkable trove of 906 letters he kept at his side as he wrote. These were letters he had written to his mother throughout his life, and which she hoarded carefully, preserving them through the storms of war and countless changes of address.

In these miniature canvases, Dahl began to hone his idiosyncratic talent for interweaving truth and fiction. It would be pedantic to list the inaccuracies in Boy or its successor Going Solo. Most of them are unimportant. A grandfather confused with a great-grandfather, a date exaggerated, a slip in chronology, countless invented details. Boy is a classic, not because it is based on fact but because Dahl had a genius for storytelling. Yet its untruths, omissions and evasions are revealing. Not only do they disclose the author’s need to embellish, they hint as well at the complex hidden roots of his imagination, which lay tangled in a soil composed of lost fathers, uncertain friendships, a need to explore frontiers, an essentially misanthropic view of humanity, and a sense of fantasy that stemmed in large part from the Norwegian blood that ran powerfully through his veins.

Norway was always important to Dahl. Though he would sometimes surprise guests at dinner by maintaining garrulously that all Norwegians were boring, he never lost his profound affection for and bond with his homeland. His mother lived in Great Britain for over fifty years, yet never renounced her Norwegian nationality, even though it sometimes caused her inconvenience—most notably when she had to live as an alien in the United Kingdom during two world wars. Although she usually spoke to her children in English and always wrote to them in her adopted language, she made sure they also learned to speak Norwegian at the same time they were learning English; and every summer she took them to Norway on holiday. Forty years later, Roald would recreate these summer holidays for his own children, reliving memories that he would later immortalize in Boy. “Totally idyllic,” was how he described these vacations. “The mere mention of them used to send shivers of joy rippling all over my skin.” Part of the pleasure was, of course, an escape from the rigors of an English boarding school, but for Roald the delight was also more profound. “We all spoke Norwegian and all our relations lived over there,” he wrote in Boy. “So, in a way, going to Norway every summer was like going home.”

“Home” would always be a complex idea for him. His heart may have sometimes felt it was in Norway, but the home he dreamed about most of the time was an English one. During the Second World War, when he was in Africa and the Middle East as a pilot and in Washington as a diplomat, it was not Norway he craved for, nor the valleys of Wales he had loved as a child, but the fields of rural England. There, deep in the heart of the Buckinghamshire countryside, he, his mother and his three sisters would later construct for themselves a kind of rural enclave: the “Valley of the Dahls,” as Roald’s daughter Tessa once described it. Purchasing homes no more than a few miles away from each other, the family lived, according to one of Roald’s nieces, “unintegrated . . . and largely without proper English friends.” For though Dahl was proud to be British and though he craved recognition and acceptance from English society, for most of his life he preferred to live outside its boundaries, making his own rules and his own judgments, not unlike his ancestor, Pastor Hesselberg.

As a result, English people found him odd. His best friend at prep school admitted that he was drawn to Roald because he was “a foreigner.” And he was. Though born in Britain, and a British citizen, in many ways Dahl retained the psychology of an émigré. Later in his life, people forgot that. They interpreted his behavior through the false perspective of an assumed “Englishness,” to which he perhaps aspired, but which was never naturally his. They saw only a veneer and they misunderstood it. In truth, Roald was always an outsider, the child of Norwegian immigrants, whose native land would become for their son an imaginative refuge, a secret world he could always call his own.

As with many children of emigrants, Roald would take on the manners and identity of his adopted home with the zeal of a convert. His sister Alfhild complained that her brother did n...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherEmblem Editions

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0771083335

- ISBN 13 9780771083334

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages704

- Rating

US$ 11.53

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl

Published by

Emblem Editions

(2011)

ISBN 10: 0771083335

ISBN 13: 9780771083334

Used

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.58. Seller Inventory # G0771083335I3N00

Buy Used

US$ 11.53

Convert currency

Storyteller: The Authorized Biography of Roald Dahl

Published by

Emblem Editions

(2011)

ISBN 10: 0771083335

ISBN 13: 9780771083334

Used

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: Good. Good condition. This is the average used book, that has all pages or leaves present, but may include writing. Book may be ex-library with stamps and stickers. Seller Inventory # 353-0771083335-gdd

Buy Used

US$ 14.14

Convert currency