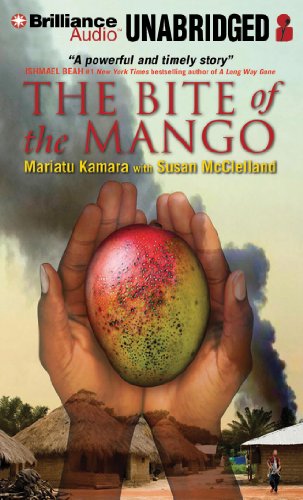

The Bite of the Mango

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1

My name is Mariatu, and this is my story. It begins the year I was 11, living with my aunt and uncle and cousins in a small village in Sierra Leone.

I'd lived with my father's sister Marie and her husband, Alie, since I was a baby. I called them Ya for mother and Pa for father, as terms of endearment. It was common in my country for children in the rural areas to be raised by people other than their birth parents.

Our village of Magborou was small, like most villages in Sierra Leone, with about 200 people living there. There were eight houses in the village, made out of clay, with wood and tin roofs. Several families lived in each house. The adults slept in the smaller rooms, and we kids usually slept together in the living room, which we called the parlor. Everyone chipped in and helped each other out. The women would all cook together. The men would fix the roofs of the houses together. And we kids played together.

None of the kids in my village went to school. My family, like everyone else in Magborou, was very poor. "We need you to help us with the chores on the farm," Marie explained. Occasionally children from wealthier families and villages would pass through Magborou on their way to and from school. Some of these children went to boarding schools in Sierra Leone's capital city, Freetown. I felt sad when I saw them. I wished I could see for myself what a big city looked like.

Starting from the time I was about seven, and strong enough to carry plastic jugs of water or straw baskets full of corn on my head, I spent my mornings planting and harvesting food on our farm outside Magborou. No one owned land in the villages; we all shared the farm. Every four years or so we rotated the crops of cassava -- which is like a potato -- peanuts, rice, peppers, and sweet potatoes.

Even though not everybody who lived in Marie and Alie's house was related by blood, we thought of each other as family, calling one another uncle, aunt, and cousin. Mohamed and Ibrahim, two of my cousins, were already living in the village when I arrived as a baby.

Mohamed was about 17 -- I wasn't entirely sure, since people in the village didn't celebrate birthdays or keep track of how old they were. Mohamed was chubby, with a soft face and warm eyes. He was always trying to make people laugh, even at funerals. Everybody would stay home and mourn when someone in the village died, usually for three days. We didn't work during that time. We sat around, and the adults would cry. But Mohamed would walk in and start making light of everyone's tears.

"If the dead hear you making such a scene," he would say, "they'll come marching back here as ghosts and take over your bodies."

People would look shocked, and Mohamed would then speak more gently. "Really," he would say, "the dead died because it was their time. They wouldn't want you spending your remaining days here on earth crying about them."

Mohamed was a good person. When food was scarce, he'd give his portion to me or the other younger kids, saying, "You eat up, because you're little and need to grow."

Ibrahim couldn't have been more different. He was about a year older than Mohamed, tall and thin. Ibrahim was bossy. When we worked at the farm, he was always telling me and the other smaller kids what to do. If we didn't obey him, he'd kick a shovel or pail or just storm off.

Ibrahim had these episodes in which his body would convulse, his eyes would get glossy, and his mouth would froth. Much later, when I moved to North America, I discovered that the disease he had is called epilepsy.

Magborou was a lively place, with goats and chickens running about and underfoot. In the afternoons I played hide-and-seek with my cousins and friends, including another girl named Mariatu. Mariatu and I were close from the moment we met. We thought having the same name was so funny, and we laughed about lots of other things too. The very first year we were old enough to farm, Mariatu and I pleaded with our families to let us plant our crops beside each other, so that we wouldn't be separated. We spent our nights dancing to the sound of drums and to people singing. At least once a week, the entire village met to watch as people put on performances. When it was my turn to participate, I'd play the devil, dressed up in a fancy red and black costume. After I danced for a while, I'd chase people around and try to scare them, just like the devil does.

I didn't see my parents often, but when I was 10 I went to visit them in Yonkro, the village where they lived. One evening after dinner, as we sat out under the open sky, my dad told me about my life before I went to live with his older sister. The stars and the moon were shining. I could hear the crickets rubbing their long legs together in the bushes, and the aroma of our dinner of hot peppers, rice, and chicken lingered in the air.

"The day you were born was a lucky day," my dad said, sucking on a long pipe filled with tobacco. "You were born in a hospital," he continued, which I knew was very unusual in our village. "Your mother smoked cigarettes, lots of cigarettes, and just before you were about to come out, she got cramps and began to bleed. If you hadn't been in the hospital, where the nurses gave you some medicine to fix your eyes, you would have been blind."

I shivered for a moment, thinking of what life would have been like then.

It was rainy and cold on the day I was born, my dad then told me. "That's a lucky sign," he laughed. "It's good to be married or have a baby on a rainy day."

For a living, my dad hunted for bush meat, which he sold at the market in a nearby town alongside the villagers' harvests. It seemed he wasn't a very good hunter, though, because I knew from Marie that he didn't make much money at it. I knew, too, that he was always getting into trouble, going in and out of jail. The jail was a cage with wooden bars, set in the middle of the village so everyone could peer in at the criminal.

In Sierra Leone, girls spend most of their time with women and other girls, not with their fathers, grandfathers, or uncles. It was nice to be talking with my dad in this way, and I listened carefully as he explained how I had come to be living with Marie and Alie.

My dad had married two women, as many men do in Sierra Leone. Sampa was the older wife; Aminatu, my mother, was the younger one. Before I was born, Sampa had given birth to two boys. Both of them died within a year of coming into the world. When Sampa was pregnant a third time, my dad asked Marie if she would take the child. That way, he hoped the child would live. Santigie, my half-brother, was born three years before me.

Soon after Santigie went to live with Marie, my mom became pregnant with my older sister. Sampa didn't like that. She was a jealous woman who wanted all of my father's attention. So when my sister was born, Sampa sweetly asked my dad to bring Santigie back to live with them.

Marie was my dad's favorite sister. At first, he told me, he didn't want to bring Santigie home, because he knew it would upset her. But eventually he did, as Sampa's sweetness turned sour. She fought with my dad until Santigie moved back in with them. Marie was very sad about it.

Wanting to make both Marie and my dad happy, my mom told Marie that she could raise the child she was expecting. "I don't know whether this child will be a boy or a girl," my mother told her. "But I promise that you can keep the child forever and ever and call him or her your own."

I went to live with Marie as soon as I had been weaned from my mother's milk. For some reason that even my dad forgot, Sampa sent Santigie back to Marie when I was about three. My half-brother and I became very close. We slept side by side on straw mats, ate from the same big plate of food, and washed each other's backs in the river. When we were older, we teased each other endlessly. But three years later, Sampa decided she wanted Santigie back again. He didn't want to go, and I didn't want him to leave either. But Marie and I had to take him back to his mother.

By then, Sampa and my mom were so jealous of each other that they'd have big fights. It was hard to understand what they were arguing about, since they spoke so fast and so loud, but they'd pull each other's hair and spit and kick. When this happened in the house, Santigie and I crept so far back that our spines were flush against the wall. Our eyes would be wide open, staring, and we'd cover our mouths with our hands to stop ourselves from laughing out loud. Two grown women fighting, with their eyes flashing, their bosoms flying, and their dresses pulled up to their waists, was a funny sight. When I saw how Sampa and my mom fought, I was happy that Marie was raising me. I only wished she could raise Santigie too.

A few months after Marie and I returned to Magborou, someone sent word that Santigie was sick. His belly stuck out like a pregnant woman's, we heard. He was so weak he couldn't even get out of bed. The medicine woman gave him all sorts of remedies, but nothing helped. And this time, my dad told me, he didn't have enough money for the hospital. Santigie died at home in the middle of the night.

A strange thing happened to me after Santigie's death. As I was walking one day, I thought I could hear his voice calling me. I turned to look, but there was no one there. This happened several times over the next year. I often wondered in the times that were to come if Santigie was a spirit watching over me.

The evening my dad told me about my early childhood, he stopped talking as some of the village children began to sing and drum in the center of town. This was the evening the townsfolk of Yonkro met to sing and dance, share stories, and gossip, just like we did every week in Magborou.

"Thank you," I whispered to my father.

He nodded his head in response, stood up, and went back into the hut to join the others.

Adamsay was Marie's youngest daughter. She had gone to live with ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBrilliance Audio

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 1455858900

- ISBN 13 9781455858903

- BindingMP3 CD

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want