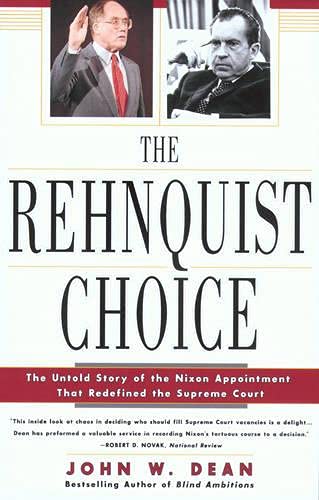

The Rehnquist Choice: The Untold Story of the Nixon Appointment That Redefined the Supreme Court

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1: Introduction: The Backstory

The heart of the story of William Rehnquist's appointment to the Supreme Court begins on September 17, 1971, and ends with an announcement on October 21, 1971. That story begins in the next chapter. First, it is important to understand the backstory.

It is well known that Richard Nixon made extraordinary use and abuse of his presidential powers. It is not widely known that those uses and abuses also related to the Supreme Court. More than any president since Franklin D. Roosevelt, he worked hard to mold the Court to his political liking. That meant not only making conservative appointments; it also meant creating appointments. William Rehnquist, who would be Nixon's most important appointment, was actively involved in the efforts to create vacancies on the Court while serving as an assistant attorney general. It is not an overstatement to say that Rehnquist, working with Nixon's attorney general, John Mitchell, and others, misused the resources and powers of the Department of Justice, and other executive branch agencies, to literally unpack the Court by removing life-tenured justices they found philosophically or politically unacceptable. It was all part of a strategy that commenced even before Nixon assumed office.

Resignation of Chief Justice Earl Warren

The scheme began during the 1968 presidential campaign. The vacancy on the Supreme Court awaiting Richard Nixon when he became president was not an accident. Nixon had made certain that that vacancy would be his to fill. During the 1968 presidential campaign, by a letter of June 13, 1968, Chief Justice Earl Warren informed President Lyndon Johnson that he wished to resign "not because of reasons of health or on account of any personal or associational problems, but solely because of age." Employing the easy candor that characterized all his decisions, Warren explained it was time "to give way to someone who will have more years ahead of him to cope with the problems which will come before the Court."

Candidate Richard Nixon, and his campaign manager and law partner John N. Mitchell, knew exactly why Earl Warren had resigned when he did, five months before the November election decision. The politically savvy Warren, a former governor of California, believed that Nixon would win. And Nixon's "law and order" presidential campaign often targeted Warren's Court. As Nixon biographer Stephen Ambrose observed, "By 1968, Nixon had become almost as critical of the Warren court as he was of the Johnson Administration. He was promising, as president, to appoint judges who would reverse some of the basic decisions of the past fifteen years. When Warren resigned, reports spread quickly that he had chosen this moment to do so because he feared that Nixon would win in November and eventually have the opportunity to appoint Warren's successor." Nixon did not attack Earl Warren personally -- as many conservatives did. But he made sure that, as president, he would select the next chief justice.

Less than two weeks after receiving word that Warren wished to retire, President Johnson called the press into the Oval Office to announce: "I have the nomination for the chief justice. The nomination will go to the Senate shortly. It is Justice Abe Fortas, of the State of Tennessee," whom Johnson had placed on the Court in 1965. To fill the Fortas seat as associate justice, Johnson added, "I am nominating Judge [Homer] Thornberry, presently on the Fifth Circuit." The Democratic president had nominated two of his closest cronies, men he knew would continue the judicial activism of the Warren Court and the liberalism that Lyndon Johnson had embraced throughout his political career. It would prove a mistake for all.

While no one could read the U.S. Senate better than Lyndon Johnson, given his many years as its majority leader, in this instance he misread his strength as a lame-duck president. With Johnson not seeking reelection, and his vice president Hubert Humphrey fading in the race with Nixon, Senate Republicans, joined by southern Democrats who were less than enamored with Justice Fortas's position on civil rights, decided to fight the Fortas nomination.

Publicly, Nixon remained above the fray. Privately, he encouraged Senator Robert Griffin (R-MI), to attack Fortas's elevation to chief justice. The effort to block the nomination took several tacks. At the outset, Senator Griffin tried to make a point of Fortas's close relationship with President Johnson, but his Republican colleague on the Judiciary Committee, Senate minority leader Everett Dirksen, dismissed that avenue. Dirksen observed that presidents regularly appointed "cronies" to the Supreme Court, citing Abraham Lincoln selecting his campaign manager David Davis, President Harry Truman appointing his private adviser Fred Vinson, and more recently President Kennedy sending his lieutenant Byron White to the Court.

As his biographer Laura Kalman notes, Fortas's opponents then found an endless arsenal among his own opinions as a member of the Warren Court that could be used against him. For example, Republican senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina spent several hours berating him about the Warren Court's criminal law holdings, even holding Fortas responsible for a ruling made before he arrived. The Senate Judiciary Committee called a witness from the Citizens for Decent Literature, who had examined fifty-two of the Court's rulings and determined that Fortas's vote had prevented the Court from finding obscenity in forty-nine of the cases. In addition, the witness had a slide show (later reviewed by the senators, and press, in a closed session) to display the types of pornographic materials he found offensive but that Justice Fortas had tolerated.

Most damaging, however, Senator Griffin received an anonymous tip from an American University employee, where Fortas was teaching a seminar at the law school, that the school had raised "an exorbitant sum from businessmen to pay Fortas's salary." At that time it was not unusual for a justice to earn outside income by teaching; but in this case the amount was relatively large -- and possibly tainted. This was reason to reopen the hearings, which revealed that Fortas's former law partner, Paul Porter, had gone to friends and clients to raise $30,000, with half going to the American University law school and the other half going to Fortas. Porter said that Fortas had not been told of this arrangement, but the Senate made much of the appearance of impropriety of Fortas's $15,000 fee, which amounted to 40 percent of a Supreme Court justice's salary at that time.

When the Fortas nomination came to the Senate floor, the Republicans mounted a historic filibuster -- the first against a Supreme Court nomination. The Johnson White House lacked the political muscle to prevent this unless, it was said, Richard Nixon urged a halt. But Nixon refused to comment publicly, and through backchannels he sent advice and praise to the Republicans' effort.10 On October 1, 1968, when the Senate failed to vote for cloture (thus ending the filibuster), Justice Fortas, realizing that his nomination was doomed, requested that Johnson withdraw it. With the Fortas nomination defeated, the Thornberry nomination became moot. Given the limited time available, Johnson could name no successor to Chief Justice Earl Warren. The vacancy for chief justice awaited Nixon.

Ousting Abe Fortas

The story of how Richard Nixon created a second opening on the Court has never been fully told. After winning in November, Nixon arranged for retiring Chief Justice Earl Warren to remain on the Court until the end of the Court term in June 1969. This gave the new president six months to select his chief justice. Ostensibly to show Earl Warren his appreciation for remaining, but in truth because Nixon wanted to size up t

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0743229797

- ISBN 13 9780743229791

- BindingDigital

- Number of pages352

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want