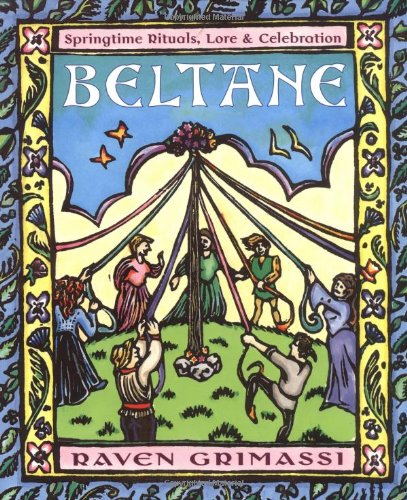

Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore, & Celebration - Softcover

Discover the roots of Beltane or "bright fire," the ancient Pagan festival that celebrates spring, and the return of nature's season of growth and renewal. In the only book written solely on this ancient Pagan festival, you'll explore the evolution of the May Pole and various folklore characters connected to May Day celebrations. Raven Grimassi reveals the history behind the revelry, and shows you how to welcome this sacred season of fertility, growth, and gain with:

·May Day magick and divination: Beltane spells to attract money, success, love, and serenity; scrying with a bowl or glass

·Beltane goodies: Quick May Wine, Bacchus Pudding, May Serpent Cake, May Wreath Cake

·Seasonal crafts: Maypole centerpiece, May wreath and garland, pentacle hair braids, May Day basket

·Springtime rituals and traditions: the Maypole dance, May doll, the Mummer's Play, Beltane fires, May King and Queen

·Myths, fairy and flower lore: Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, Dusio, Hobby Horse; elves, trolls and fairies; spring flowers and their correspondences

This well-researched book corrects many of the common misconceptions associated with May Day, and will help you appreciate the spirituality and connection to Nature that are intimate elements of May Day Celebrations. Welcome the season of fertility, flowers, and fairies with Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore & Celebration.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Raven Grimassi is a Neo-Pagan scholar and award-winning author of more than eighteen books on Witchcraft, Wicca, and Neo-Paganism. He has been devoted to the study and practice of witchcraft for over forty years. Raven is co-founder and co-director of the Ash, Birch, and Willow tradition.

Grimassi’s background includes training in old forms of witchcraft as well as Brittic Wicca, the Pictish-Gaelic tradition, Italian Witchcraft, and Celtic Traditionalist Witchcraft. Raven was also a member of the Rosicrucian Order, and studied the Kabbalah through the First Temple of Tifareth under Lady Sara Cunningham.

Raven currently lives in New England with his wife and co-author Stephanie Taylor-Grimassi. Together they direct The Fellowship of the Pentacle, a modern Mystery School devoted to preserving pre-Christian European spirituality.

THE CELEBRATION

OF MAY

I sing of brooks, of blossoms, birds, and bowers;

Of April, May, of June, and July-flowers,

I sing of May-poles, Hock-carts, wassails, wakes,

Of bride-grooms, brides, and of their bridal-cakes.

?Robert Herrick

Since ancient times the May season has been a time of celebration and merriment. The appearance of flowers after a cold winter season signals the promise of warm summer days to come. Many of the modern celebrations of May are rooted in ancient pagan traditions that honored the earth and the forces that renewed life. In many pre-Christian European regions, Nature was perceived as a goddess and from this ancient concept evolved the modern ?Mother Nature? personification.

May Day celebrations are a time to acknowledge the return of growth and the end of decline within the cycle of life. The rites of May are rooted in ancient fertility festivals that can be traced back to the Great Mother festivals of the Hellenistic period of Greco-Roman religion. The Romans inherited the celebration of May from earlier Latin tribes such as the Sabines. The ancient Roman festival of Floralia is one of the celebrations of this nature. This festival culminated on May 1 with offerings of flowers and garlands to the Roman goddesses Flora and Maia, for whom the month of May is named. Wreaths mounted on a pole, which was adorned with a flowered garland, were carried in street processions in honor of the goddess Maia.

With the expansion of the Roman Empire into Gaul and the British Isles, the festivals of May were introduced into Celtic religion. Various aspects of May celebrations such as the blessing of holy wells are traceable to the ancient Roman festival of Fontinalia, which focused upon offerings to spirits that revived wells and streams. Even the Maypole itself is derived from archaic Roman religion. In the Dictionary of Faiths & Folklore by W. C. Hazlitt (London: Bracken Books, 1995), the author states that in ancient Briton it was the custom to erect Maypoles adorned with flowers in honor of the Roman goddess Flora.

The Maypole is traditionally a tall pole garlanded with greenery or flowers and often hung with ribbons that are woven into complex patterns by a group of dancers. Such performances are the echoes of ancient dances around a living tree in spring rites designed to ensure fertility. Tradition varies as to the type of wood used for the maypole. In some accounts the traditional wood is ash or birch, and in others it is cypress or elm. The Maypole concept can be traced to a figure known as a herms (or hermai) that was placed at the crossroads throughout the Roman Empire.

A herms is a pillar-like figure sporting the upper torso of a god or spirit. The herms was a symbol of fertility and it was often embellished by an erect penis protruding from the pillar. The earliest herms were simply wooden columns upon which a ritual mask was hung. In time, to reduce replacement costs, the Romans began making the herms from stone instead of wood. In May, the herms was adorned with flowers andgreenery, and sacred offerings were placed before it. This and other practices of ancient Italian paganism were carried by the Romans throughout most of continental Europe and into the British Isles. For further information on this topic the reader is referred to Dionysos: Archetype Image of Indestructible Life by Carl Kerenyi (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976, pp. 380?381).

In 1724 the noted occultist Dr. William Stuckely, in his work titled the Itinerarium, describes a Maypole near Horn Castle, Lincolnshire, that reportedly stood on the site of a former Roman herms (a wood or stone carving of the upper torso of a body emerging from a pillar). The author records that boys ?annually keep up the festival of the Floralia on May Day,? and carried white willow wands covered with cowslips. Stuckely goes on to say that these wands are derived from the thyrsus wands once carried in the ancient Roman Bacchanal rites. For further information on this, I refer the reader to Hazlitt?s Dictionary of Faiths & Folklore (pp. 402?406).

May festivals commonly incorporate elements of pre-Christian worship related to agricultural themes. In ancient times a young male was chosen to symbolize the spirit of the plant kingdom. Known by such names as Jack-in-the-Green, Green George, and the Green Man, he walked in a procession through the villages symbolizing his return as spring moves toward summer.

Typically a pretty young woman bearing the title ?Queen of the May? led the procession. She was accompanied by a young man selected as the May King, typically symbolized by Jack-in-the-Green. The woman and man, also known as the May Bride and Bridegroom, carried flowers and other symbols of fertility related to agriculture.

The connection of the tree to May celebrations is quite ancient and is rooted in archaic tree worship throughout Europe. The belief that the gods dwelled within trees was widespread. Later this tenet diminished into a belief that the spirit of vegetation resided in certain types of trees, such as the oak, ash, and hawthorn. In many parts of Europe young people would gather branches and carry them back to their villages on May 1 morning, suspending them in the village square from a tall pole. Bringing newly budding branches into the village was believed to renew life for everyone. Dances were performed around this ?Maypole? to ensure that everyone was connected or woven into the renewing forces of Nature.

The garland of flowers, associated with May rituals, is a symbol of the inner connections between all things, symbolic of that which binds and connects. Garlands are typically made from plants and flowers that symbolize the season or event for which the garland is hung as a marker or indicator. In ancient Greek and Roman art many goddesses carry garlands, particularly Flora, a flower goddess associated with May. The Maypole is often decorated with a garland as a symbol of fertility, in anticipation of the coming summer and harvest season.

Among the Celtic people the celebration of May was called Beltane, meaning ?bright fire,? due to the bonfires associated with the ancient rites of this season. This festival occasion was designed as a celebration of the return of life and fertility to a world that has passed through the winter season. It is the third of the four great Celtic fire festivals of the year: Beltane, Imbolc, Lughnasahd, and Samhain. Beltane was traditionally celebrated at the end of April. Many modern Wicca Traditions celebrate Beltane on May 1 or May Eve. Along with its counterpart of Samhain, Beltane divided the Celtic year into its two primary seasons, winter and summer. Beltane marked the beginning of summer?s half and the pastoral growing season.

Continental Celts worshipped a god known as Belenus. The root word ?Bel? means bright, whether associated with fire or with a light such as the sun. As noted earlier, the word ?Beltane? literally means ?bright fire? and refers to bonfires (known as ?need-fire?) lit during this season. Bel-tane may or may not be derived from the worship of the Celtic deity Belenus (MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 35). In ancient times Beltane heralded the approach of summer and the promise of fullness. Herds of cattle were ritually driven between two bonfires as an act of purification and protection. This was believed to ensure their safety and fertility throughout the remainder of the year. The fires celebrated the warmth of the sun, and its power to return life and fruitfulness to the soil. Ashes from the sacred bonfires lit at Beltane were scattered over the fields to ensure fertility. An old Welsh custom was to take some ash home for protection, or to put ashes in one?s shoe to guard against misfortune.

Many modern Wiccans/Witches believe that the Beltane festival was held in honor of the god Bel. In some modern traditions he is also known as Beli, Balar, Balor, or Belenus. Authors Janet and Stewart Farrar point out that some people have suggested that Bel is the Brythonic Celt equivalent of the god Cernunnos. (Farrar, Janet & Stewart. Eight Sabbats for Witches. London: Robert Hale, 1981, pp. 80?81). In modern Wicca/Witchcraft, Beltane marks the appearance of the Horned One, who is the rebirth of the solar God slain during the Wheel of the Year. He then becomes consort to the Goddess, impregnating Her with his seed, and thereby ensuring his own rebirth once again. In the evolution of god images, he became the Harvest Lord of agrarian society. In this regard the god is associated with the Green Man, a popular image connecting the god to the ever-returning cycle of foliage and flowering.

Southern European traditions, such as those of old Italy, celebrate the ripeness of May by tying ribbons and lemons around flowering branches. Potted trees, anointed male and female, are brought into a plaza and married in a mock ceremony. As with all things Italian, food is in abundance and traditional meals are served. Groups of people join together in street processions led by a young woman who carries a garlanded branch decorated with ribbons, fresh fruits, and lemons.

One very interesting observance of May is held in the mountainous region near Cocullo, just east of Rome. Here the inhabitants gather in a snake festival. The snakes are carried into the plaza in terracotta jugs filled with grain. The snakes are then handled by keepers and carried around their shoulders. Observers are coaxed into holding the snakes and the festival becomes very exciting. The origin of this festival is traceable to the ancient rites of an Italic people known as the Marsi. They worshipped a snake goddess known as Angizia. In time legends aroseassociating her with Circe, an ancient Greek sorceress. Today the goddess Angizia has been replaced by Saint Domenico, who is said to protect people from poisonous snakes. Saint Domenico was previously associated with a miracle connected to the growth of fava beans. Both snakes and fava beans are intimately connected in Italic paganism to themes of emergence from the Underworld.

The snake was first associated with the month of May as a fertility symbol. To the ancients, the snake penetrated the earth, an act suggestive of sexual intercourse. Because the earth was a fertile region, the snake was believed to possess its inner secrets by disappearing into the depths below. In occult lore the snake represents the inner knowledge of creation and is considered a guardian of the waters of life. Due to their ability to shed their skin, snakes symbolize rebirth and eternal life, one of the reasons why snakes appear on the caduceus symbol worn by medical professionals.

In his Dictionary of Faiths & Folklore, author W. C. Hazlitt recounts a custom practiced among the ancient Romans where young boys ?go out Maying? on April 30 to collect branches for celebrating the first of May. A similar custom is still observed today among the Cornish, who decorate their doorways on the first of May with green boughs of sycamore and hawthorn. In Huntingdonshire, people gather sticks for fuel on May Day, an act perhaps related to the Druidic custom of lighting fires on May Day atop the Crugall (Druid?s Mound). In northern England it was long the custom to rise at midnight and gather branches in the neighboring woods, adorning them with nosegays and crowns of flowers. At sunrise the gatherers would return home and decorate their doors and windows. In Ireland it was once the custom to fasten a green bough against the home on the first of May to ensure an abundance of milk in the coming summer. Ancient Druids were said to have herded cattle through an open fire on this day in a belief that such an act would keep the cattle from disease all year.

A curious custom of the past called ?May Birching? seems to have evolved from the ancient symbolism of trees. On May Eve, participants called ?May Birchers? went about various neighborhoods affixing branches or sprigs to the doors of selected houses. The symbolism of what they left there was meant to indicate their sentiments regarding those who dwelled in the respective homes. To leave gorse (in bloom) meant that the woman of the house had a bad reputation. This may be related to an old saying in Northamptonshire: ?When gorse is out of bloom, kissing is out of season.? The branch of any nut-bearing tree was a sign of open promiscuity. The flowering branch of a hawthorn was a compliment, indicating that the occupants were well liked in the community. However, any other type of thorn indicated that the inhabitants were scorned. The presence of a rowan meant that the people were well loved. To leave briar was an indication that the people were untrustworthy.

Another May custom connected to the theme of gathering is the collection of dew in the early morning on May 1. Among the ancient Romans the dew was sacred to the goddess Diana, who was also known as ?The Dewy One.? It was believed that the moon left the morning dew during the night. In Italian Witchcraft dew is collected from several sacred plants and is then used as a type of holy water. This holy dew-water of May is believed to bestow good fortune throughout the year. In some parts of Britain young country girls go out just before sunrise on May Day and collect dew from the plants. The dew is then applied to their faces in the belief that it will keep their complexions beautiful and will remove blemishes.

The May garland is an emblem of summer and is decorated with bright ribbons, fresh leaves, and every type of flower available at the season. Traditionally the May doll is hung suspended inside the hoop of the garland. Garlands have long been associated with May and their use in May celebrations is traceable to the ancient Roman festival of Flora. In the British Isles, peeled willow wands often sport May garlands. The May staves are often adorned with posies or wreaths of cowslips. At Horncastle in Lincolnshire it was once the custom to carry adorned wands in a procession culminating in their placement on a hill where an ancient Roman temple once stood. The flowers of the foxglove plant are traditionally set in place on the May garland in honor of the fairies. (See pp. 143?144 for directions for constructing a May garland.)

THE Maypole

The Maypole is the symbol of the spirit of vegetation returning and renewing its life with the approach of summer. Traditionally the Maypole was topped with a wreath that symbolized the fertile power of Nature. Ribbons, an ancient talisman of protection dating back to archaic Roman religion, were attached to the pole to ensure the safety of the newborn season. Celebrants encircled the pole and danced in a symbolic weaving of human life with the life of Nature itself.

The Maypole appears to have evolved from archaic Roman religion where it began as an object known as a herms, as noted earlier in this chapter. However, some commentators believe that the Maypole originates from the Phrygian pine tree of Attis carried in the sacred processions related to the temple of Cybele. In ancient Roman religion this was connected with the festival known as Hilaria, a joyful rite of merriment that included dancing around a pole. With the spread of Roman influence into northern Europe these elements of Italic paganism were absorbed into Celtic and Germanic religion.

The traditional Maypole dance is both a circular and a spiral dance. It involves alternation of male and female dancers who move in and out from the center to ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherLlewellyn Publications

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 1567182836

- ISBN 13 9781567182835

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages192

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore, Celebration

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1567182836

Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore, Celebration

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1567182836

Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore, & Celebration

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB1567182836

BELTANE: SPRINGTIME RITUALS, LOR

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.86. Seller Inventory # Q-1567182836

Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore, Celebration

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1567182836

Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore, Celebration

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1567182836

Beltane

Book Description Condition: New. First Edition. First Edition thus. Beltane by Raven Grimassi. ISBN:9781567182835. Collectible item in excellent condition. Seller Inventory # 1567182835