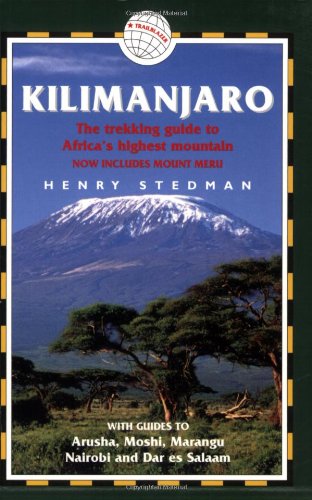

Kilimanjaro: The Trekking Guide to Africa's Highest Mountain - 2nd Edition; Now includes Mount Meru - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

"Kilimanjaro is a snow covered mountain 19,710 feet high, and is said to be the highest mountain in Africa. Its western summit is called the Masai 'Ngà'je Ngài', the House of God. Close to the western summit there is the dried and frozen carcass of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude". Ernest Hemingway in the preamble to The Snows of Kilimanjaro

Ostensibly, climbing Kilimanjaro seems straightforward. After all, no technical skill is required to reach the summit of Africa's highest mountain beyond the ability to put one foot in front of the other; because, unless you go out of your way to find an awkward route, there is no actual climbing involved at all - just lots and lots of walking. Thus, anyone above the age of 10 (the minimum legal age for climbing Kilimanjaro) with the right attitude, a sensible approach to acclimatization, a half-decent pair of calf muscles and lots of warm clothing can make it to the top.

That, at any rate, is the theory, and one that a glance at the recent history of climbing Kilimanjaro would seem to bear out. With kids as young as twelve and pensioners as venerable as the Frenchman, Valtée Daniel, at 87 being the oldest man to stand on the summit, Kili conquerors come in all shapes and sizes.

The cynical could look upon the large numbers of trekkers climbing Kili as evidence that this is a relatively easy mountain to scale. For further proof, they could also point to those for whom the challenge of climbing Kilimanjaro simply wasn't, well, challenging enough, and who deliberately went out of their way to make the ascent more difficult for themselves, just for the hell of it. Men such as the Brazilian who jogged right up to the summit in just 24 hours. Or the Crane brothers from England who cycled up, surviving on Mars Bars strapped to their handlebars. And the anonymous Spaniard who, in the 1970s, drove up to the summit by motorbike. Nor must we forget Douglas Adams, the author of the Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy, who in 1994 reached the summit for charity while wearing an eight-foot rubber rhinoceros costume; and finally there's the (possibly apocryphal) story of the man who walked backwards the entire way in order to get into the Guinness Book of Records - only to find out, on his return to the bottom, that he had been beaten by somebody who had done exactly the same thing just a few days previously.

And that's just the ascent; for coming back down again the mountain has witnessed skiing, a method first practiced by Walter Furtwangler way back in 1912; snowboarding, an activity pioneered on Kili by Stephen Koch in 1997; and even hang-gliding, for which there was something of a fad a few years ago.

Cyclists to skiers, heroes to half-wits, bikers to boarders to backward walkers: it's no wonder, given the sheer number of people who have climbed Kili over the past century, and the ways in which they've done so, that so many believe that climbing Kili is something of a doddle. And you'd be forgiven for thinking the same.

You'd be forgiven - but you'd also be wrong. Whilst these stories of successful expeditions tend to receive a lot of coverage, they serve to obscure the tales of suffering and tragedy that often go with them. You don't, for example, hear much about the hang-glider who leapt off Kili a few years ago and was never seen again. Or the fact that the Brazilian who jogged up spent the next week in hospital recovering from severe high-altitude pulmonary edema. And for all the coverage of the Millennium celebrations, when over 7000 people stood on the slopes of Kilimanjaro during New Year's week - with a 1000 on New Year's Eve alone - little mention was made of the fact that three people died on Kilimanjaro in those seven days. Or that another 33 had to be rescued. Or that well over a third of all the people who took part in those festivities failed to reach the summit, or indeed get anywhere near it.

For once, statistics give a reasonably accurate impression of just how difficult climbing Kili can be. According to the park authorities' own estimates, only 40-50% of climbers who climb up Kilimanjaro successfully reach the summit. They also admit to there being a couple of deaths per annum on Kilimanjaro; independent observers put that figure as high as ten.

The fact that the Masai call the mountain the 'House of God' seems entirely appropriate, given the number of people who meet their Maker every year on the slopes of Kili. The high failure and mortality rates speak for themselves: despite appearances to the contrary, climbing Kilimanjaro is no simple matter.

'Mountain of greatness'

But whilst it isn't easy, it is achievable. As mentioned at the start, almost anyone in reasonable

lochcondition can climb this mountain.

It is this 'inclusivity' that undoubtedly goes some way to explaining Kilimanjaro's popularity, a popularity that saw 20,351 foreign tourists and 674 local trekkers visit in 2000, thereby confirming Kili's status as the most popular of the so-called 'Big Seven', the highest peaks on each of the seven continents. The sheer size of it must be another factor behind its appeal. This is the Roof of Africa, a massive massif 60km long by 80km wide with an altitude that reaches to a fraction less than 6km above sea level. The renowned anthropologist, Charles Dundas, writing in 1924 claimed that he once saw Kilimanjaro from a point over 120 miles away. It is even big enough to have its own weather systems (note the plural) and, furthermore, to influence the climates of the countries that surround it.

The aspect presented by this prodigious mountain is one of unparalleled grandeur, sublimity, majesty, and glory. It is doubtful if there be another such sight in this wide world.

Charles New, the first European to reach the snow-line on Kilimanjaro, from his book Life, Wanderings, and Labours in Eastern Africa

But size, as they say, isn't everything, and by themselves these bald figures fail to fully explain the allure of Kilimanjaro. So instead we must look to attributes that cannot be measured by theodolites or yardsticks if we are to understand the appeal of Kilimanjaro.

In particular, there's its beauty. When viewed from the plains of Tanzania, Kilimanjaro conforms to our childhood notions of what a mountain should look like: high, wide and handsome, a vast triangle rising out of the flat earth, its sides sloping exponentially upwards to the satisfyingly symmetrical summit of Kibo; a summit that rises imperiously above a thick beard of clouds and is adorned with a glistening bonnet of snow. Kilimanjaro is not located in the crumpled mountain terrain of the Himalayas or the Andes. Where the mightiest mountain of them all, Everest, just edges above its neighbors - and look less impressive because of it - Kilimanjaro stands proudly alone on the plains of Africa. The only thing in the neighborhood that can even come close to looking it in the eye is Mount Meru, a fair way off to the south-west and a good 1420m smaller too. The fact that it's located smack bang in the heart of the sweltering East African plains, just a few degrees and 330km south of the equator, with lions, giraffes, and all the other celebrities of the safari world running around its base, only adds to its charisma.

And then there's the scenery on the mountain itself. So massive is Kilimanjaro, that to climb it is to pass through four seasons in four days, from the sultry rainforests of the lower reaches through to the windswept heather and moorland of the upper slopes, and on to the arctic wastes of the summit.

There may be 15 higher points on the globe; there can't be many that are more beautiful, or more tantalizing.

In sitting down to recount my experiences with the conquest of the "Ethiopian Mount Olympus" still fresh in my memory, I feel how inadequate are my powers of description to do justice to the grand and imposing aspects of Nature with which I shall have to deal. Hans Meyer, the first man to climb Kilimanjaro, in his book Across East African Glaciers - an Account of the First Ascent of Kilimanjaro.

Nor is it just tourists that are entranced by Kilimanjaro; the mountain looms large in the Tanzanian psyche too. Look at their supermarket shelves. The nation's second favorite lager is called Kilimanjaro. The third favorite, Kibo Gold, is named after the higher of Kilimanjaro's two summits. Even the nation's best selling lager, Safari, has something distinctly white and pointy looming in the background of its label. Nor can teetotalers entirely escape Kili's presence. There's Kilimanjaro coffee (grown on the mountain's fertile southern slopes) and Kilimanjaro mineral water (bottled on its western side). On billboards lining the country's highways Tanzanian models smoke their cigarettes in its shadow, while cheerful roly-poly housewives compare the whiteness of their laundry with the mountain's glistening snows. And to pay for all of these things you can use a Tanzanian Ts5000 note - which just happens to have, on the back of it, a herd of giraffe lolloping along in front of the distinctive silhouette of Africa's highest mountain.

It is perhaps no surprise to find, therefore, that when Tanganyika won its independence from Britain in 1961, one of the first things they did was plant a torch on its summit; a torch that the first president, Julius Nyerere, hoped would '...shine beyond our borders, giving hope where there was despair, love where there was hate, and dignity where before there was only humiliation.'

To the Tanzanians, Kilimanjaro is clearly much more than just a very large mountain separating them from Kenya. It's a symbol of their freedom, and a potent emblem of their country.

And given the tribulations and hardships willingly suffered by thousands of trekkers on Kili each year - not to mention the money they spend for the privilege of doing so - the mountain obviously arouses some pretty strong emotions in non-Tanzanians as well. Whatever the emotions provoked in you by this wonderful mountain, and however you plan...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherUNKNO

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 1873756917

- ISBN 13 9781873756911

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number2

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Kilimanjaro: The Trekking Guide to Africa's Highest Mountain - 2nd Edition; Now includes Mount Meru

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1873756917

Kilimanjaro: The Trekking Guide to Africa's Highest Mountain - 2nd Edition; Now includes Mount Meru

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1873756917

Kilimanjaro: The Trekking Guide to Africa's Highest Mountain - 2nd Edition; Now includes Mount Meru

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1873756917

Kilimanjaro: The Trekking Guide to Africa's Highest Mountain - 2nd Edition; Now includes Mount Meru

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1873756917

KILIMANJARO: THE TREKKING GUIDE

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.71. Seller Inventory # Q-1873756917