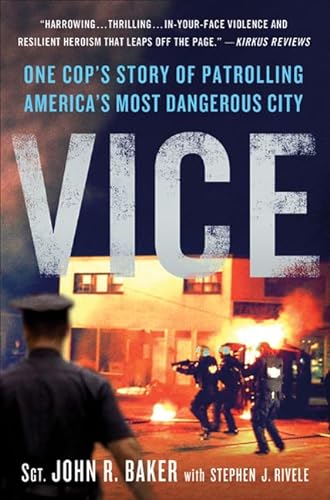

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

A Model Community

I was not born in Compton, but I grew up there.

My father moved to the Boyle Heights section of Los Angeles in 1927 from Tucson, where his father had lived. My original family name was Boulanger, which is the French word for a baker. My father’s grandfather had served with the Emperor Maximilian’s army in Mexico. After the defeat of the French by the Mexican army at the Battle of Puebla in 1862 (which is still celebrated as Cinco de Mayo), he relocated to Arizona, and his name was Anglicized from Jean Boulanger to John Baker. An industrious man, my great-grandfather worked at many trades, from rancher and barber to railroad man, saloon keeper, and prospector. Before long he owned several small apartment buildings, which he rented to the poorer folk of Tucson. When my father was ten years old, my grandfather moved his family of six sons and three daughters to Los Angeles in search of fortune and adventure.

My mother, the child of Mexican immigrants, was born in Silver City, New Mexico. Her parents relocated to Santa Ana, south of Los Angeles, when she was little; then, later, they moved into Boyle Heights in the southern L.A. suburbs. It was there, in 1940, that my mother and father met, fell in love, and married. Then the attack on Pearl Harbor thrust the United States into war, and my father was drafted and sent to Europe. He was in the third wave of the D-day invasion, fought across Europe to the Rhine, and was severely wounded.

After the war, my parents settled in the Aliso Village section of Boyle Heights, in a housing project that was built for low-income workers who could not afford to buy a home. As I recall, they paid twenty-six dollars a month in rent, and had a hard scrabble to find even that much. Aliso Village was one of the poorest neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

Boyle Heights, in the 1930s and ’40s, was largely a Jewish community, with kosher butchers and orthodox synagogues and Hebrew schools, dominated by the organized crime mob of Mickey Cohen. I often saw his shiny black Packard parked outside his headquarters, a shoeshine parlor on Brooklyn Avenue. The hood was surmounted by a big chrome swan, and everyone in the neighborhood knew that you did not touch Mr. Cohen’s car.

By the time my parents reached it, Boyle Heights was transforming. Latinos were moving from Mexico and Central America, as were blacks from the South, lured by the promise of cheap housing and jobs in the defense industries of Los Angeles. In a process I would see replicated later in Compton, the demographics of the neighborhood quickly began to change.

By the time I was born at White Memorial Hospital in 1942, Boyle Heights had become a tough and eclectic community. Life was a struggle, and everyone was out to make a living, make a killing, make a fast buck. There were legitimate small businessmen and hustlers, zoot-suited flash boys and big-band swingers, soldiers and sailors and their families eager to do their part and wishing the war were over—and Mickey Cohen’s gangsters, who ran the betting pools and numbers games, promising to make you rich or break your legs.

In addition to the immigrant Jews, many ethnic groups and languages were represented in the neighborhoods, yet there was no sense of animosity. Everyone was in the same boat, and there was none of the hostility and territorialism that would later characterize Compton. All this was tempered, of course, by the wartime mentality. Both of my parents’ families were caught up in the hurricane of war. Five of my uncles served in Europe, the oldest, Lefty Baker, being killed in the D-day invasion. His body remains in Normandy, the homeland of his ancestors. The war and the struggle against tyranny trumped everything else. No matter how different we were, no matter what our ethnic rivalries, we were all fighting the same enemy in a life-and-death struggle to save our civilization.

There was another constant in those days and in those neighborhoods: the police. It was the cops, and not the kids or the crooks, who controlled the streets of Boyle Heights. The police were strict and stolid, and you defied them at your peril. No matter how wild we kids ran, we knew that the absolute barrier to lawlessness was the LAPD. A blue-suited cop would grab you by the collar, shake the mischief out of you, smack you across the butt with his nightstick, or crack your skull if you got too far out of line. The police were the great common denominator of our hustling and hybrid neighborhood. What it lacked in homogeneity, the cops more than made up for with their authority. As a result, I learned to respect the police, and though I was careful not to cross them, I regarded them with admiration, and even awe.

I spent my first nine years in Boyle Heights, and that experience, seen now through the prism of adulthood, served me well later when I lived in Compton. In school and on the streets I learned to deal with every sort of person, from the sons of rabbis to black transplanted Alabama sharecroppers to the “wetbacks” who had only recently risked their lives in the deserts along the border to reach America. Their children were my schoolmates and my playmates, and from them I absorbed a level of tolerance and unthinking acceptance that proved later in my life to be a rare and valuable gift. In my personal relations and my choice of friends, I never saw color, never heard an accent, never assumed that anyone was any better or worse than me just because of the color of his skin or the way he talked. Boyle Heights was my preparation for my life in Compton.

In 1945, my father returned from the war in Europe with disabling injuries to his lungs, kidneys, and shoulder. He spent two years in a veterans’ hospital before he was well enough to come home. During that period I rarely saw him, so much of the bonding experience I should have had with him was lost. My father remained for me a remote, nearly inaccessible figure, rarely affectionate and often critical. Whether it was his nature or the result of his wounds I never knew.

Through my mother’s hard work and thrift, and with some help from the GI Bill, by 1950 my parents had saved enough money to buy a house. Boyle Heights and the surrounding areas proved too expensive, but they discovered that houses were affordable in the city of Compton to the south. At that time, Compton was 98 percent white, a tightly knit community dominated by Mormons. There were two Mormon temples in the city, and the mayor, Elder Del Clawson, later served in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Compton had a reputation as a progressive community that welcomed newcomers and valued its independence from Los Angeles. Modest individual houses were springing up in the western part of the city, which real estate agents advertised as being open to “veterans of all races.” They were all of a plan, some with two bedrooms and some with three, and selling for nine to ten thousand dollars.

My parents found a house on the corner of 136th Street and Central Avenue in the heart of West Compton and made the down payment. The real estate agent, Mr. Davenport, warned them that the neighborhood was likely to undergo a transformation. He was quite up-front and honest about it, and told my parents that, while the eastern part of Compton was steadfastly white, West Compton was being touted as a future home for lower-middle-class blacks who were hunting jobs in the factories of South L.A.

“Things are going to change here, and soon,” he told them as I stood in the parlor of the first real home we had ever owned. But I paid no attention to him. Across from the house, on what became Piru Street, was a helicopter testing ground busy with the exotic shapes of aircraft and the thrum of spinning rotors, and nearby on Central Avenue was a horse farm where cowboys taught kids to ride for fifty cents. After the cramped apartment in Boyle Heights, the prospect of airplanes and horses within walking distance was thrilling beyond my imagination. To my nine-year-old mind, Compton was a fairyland, a place of wonder and adventure to rival anything my grandfather had come to California to find.

* * *

In 1784, during the Spanish occupation of California, the new king, Ferdinand VII, deeded seventy-five thousand acres of ranchland, called Rancho San Pedro, to Juan Josť Dominguez. It remained a privately held ranch until the Mexican War, after which American settlers began moving into the area in search of open land and a mild climate. In 1867, a minister and pedagogue from Virginia named Griffith Dickinson Compton led a group of settlers to the area and created a town, which some twenty years later was incorporated as a city named after him. Griffith Compton had a vision of a community of farmers, householders, and scholars that would serve as a model to the Southern California region. He established a school system and a library, as well as a college that grew over the decades into Compton College, which I would one day attend.

From its founding in 1889 until the year we arrived, 1951, Compton had been an almost all-white city. Originally an agricultural settlement, it was a haven for people fleeing the urban sprawl to the north. Its open fields, trim homesteads, ranches, and farms had proved irresistible to those seeking a refuge from the increasingly oppressive crush and clamor of Los Angeles. There had, however, always been a belt of black residents, stretching along Central Avenue right down from South Central L.A. to the city of Long Beach. Compton tolerated these hardworking middle-class blacks, who confined themselves to one small district in the western part of the city and showed little inclination to move beyond it until the aftermath of World War II.

It was then that Compton real estate interests began to open up the northwestern neighborhoods to black veterans and migrants from the Deep South. What had once been meadows and farmland quickly developed into low-income tract housing, stretching through West Compton from 127th Street at the southern L.A. border to Rosecrans Avenue along Central Avenue. This was the very neighborhood into which my parents moved.

Compton in those days was something like a model community; indeed, in 1952 it was designated an “All-America City” by the National Civic League. It consisted of tidy, well-planned streets and boulevards with palm trees and pin-striped lanes, and single-family houses with landscaped yards, resembling a precocious child’s layout of a train platform. Burris, Sloan, and Poinsettia avenues off Compton Boulevard framed a neighborhood of luxurious homes with broad lawns and wrought-iron gates, which came to be known as Compton-Hollywood. The downtown shopping district was lined with trees and fronted with prosperous small businesses, and in the pedestrian walkways there was piped-in music to entertain passersby. To this day I have never heard of another urban commercial district that plays music for the enjoyment of shoppers.

There were two theaters and the only drive-ins in southeastern Los Angeles. The city had its own college, which was prized not just for the quality of its education but for its football teams as well. Compton College was considered to be a farm school for the University of Southern California, since its coach, Hall of Famer Tay Brown, was said to be able to get any Compton College player into USC on his recommendation alone. When I attended the college, my tennis coach was Ken Carpenter, who had won a gold medal in discus at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Compton got its nickname “the Hub,” because the city was equidistant from Los Angeles and Long Beach, and most of the commercial traffic between the ports of those cities had to pass through. This gave Compton, despite its small size—a mere nine square miles—a cosmopolitan flavor. It was, for example, a center of country and western music. Cowboy bars drew sailors from the naval base at Long Beach, and a local celebrity, Spade Cooley, became a national figure through his televised hootenanny, which was broadcast from a studio in Compton.

Music was always part of the life of the city. In addition to the piped-in music of the downtown district, there were amateur performers on the street corners and in the clubs and malt shops experimenting with new sounds and new dances, a practice that was to flourish in later years. Even in the fifties, Compton was a cradle of musical movements. A local group called the Six Teens scored a nationwide hit with the song “A Casual Look,” and another Compton combo, the Hollywood Argyles, who worked at Bishop’s malt shop on Long Beach Boulevard, produced the doo-wop hit “Alley Oop.” Later, the fusion group War developed in Compton, spawning such hits as “Low Rider,” “Cisco Kid,” and “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”

It seemed that all the kids of Compton were into some kind of music. My friends and I used to meet on the corner of 134th and Central Avenue to harmonize impromptu doo-wops and “ham bones.” One of my best buddies was a bright Hispanic kid named Jesse Sida who lived on Slater Street, a stone’s throw from my parents’ house. Jesse knew all the latest dances, and he taught me his moves in the local clubs and at the Pike on the pier in Long Beach. We wore three-quarter-length jackets and roll-cuff Levi’s, and we slicked our hair into a “waterfall.” We bought our bell-bottoms and lavender shirts at Sy Devore’s on Melrose (they had to be lavender because of West Side Story) and did the Slob, the Stroll, the Watusi, the Bristol Stomp, and the Slauson Shuffle. I became a pretty good dancer, and I learned very quickly that dancing was a great way to meet girls.

One of the girls I met was Lorraine Mayor. I was burning up the floor at the Cinnamon Cinder in Hollywood one night when she asked if she could dance with me. She was a cute little blonde who lived in the exclusive L.A. suburb of Hidden Hills, and she drove her daddy’s new white Cadillac to the popular dance clubs. She told me she had never seen a boy who could dance as well as I, and soon we were partnering and winning trophies together. Her father was wealthy, and Lorraine gave me her gasoline credit card so that Jesse Sida and I could drive out to Hidden Hills in my ’55 Chevy to pick her up and go dancing.

Above all, Compton was autonomous. It had its own city government, its own police force, its own water and power. Its Mormon fathers were so proud of the city’s independence that when the first shopping mall was proposed for the southern Los Angeles region the city council turned it down, fearing that it would detract from the downtown shopping district and draw in too many outsiders from L.A. Still later, when the adjacent city of Carson asked that Compton annex it so that Carson could share in Compton’s prosperity, the city fathers again refused, though Carson was twice the size of Compton and offered a huge potential for expansion of its revenue base. So confident was Compton in those days, and so sure of its integrity and of its future, that it played the role of the unobtainable princess who remained aloof, though courted by suitors from across the Southland.

* * *

My family moved into our new house in time for me to enroll at St. Leo’s school in the Watts section of Los Angeles. My parents were determined tha...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Press

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0312596871

- ISBN 13 9780312596873

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages432

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks60325

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 432 pages. 9.50x6.25x1.50 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City Baker, John R. and Rivele, Stephen J.

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.3. Seller Inventory # Q-0312596871

Vice: One Cop's Story of Patrolling America's Most Dangerous City

Book Description Condition: new. First Edition. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. Seller Inventory # PSN0312596871