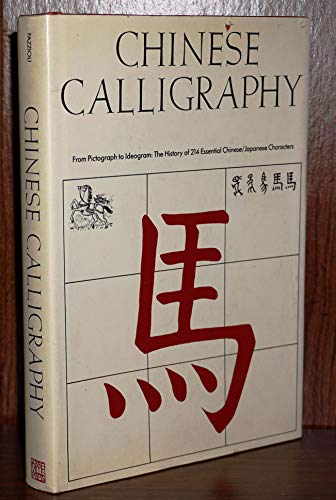

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters - Hardcover

Written Chinese can call upon some 40,000 characters, many of which originated about 6,000 years ago as little pictures of everyday objects used by the ancients to communicate with each other. This book, which introduces the Westerner to a rich and mysterious world, is based on a classic compilation of the Chinese language done in the 18th century, which determined that all the characters then in use were devised from 214 root pictographs or symbols. Each of these 214 key characters, called radicals is charmingly explored by the author, both for its etymology and for what it reveals about Chinese history and culture. Chinese characters are marvels of graphic design, and this book shows, stroke by stroke, how each radical is written and gives examples of how radicals are combined with other radicals and character elements to form new characters.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

A Living Language, Six Thousand Years Old

Many great civilizations have punctuated man’s presence on earth, but only the Chinese civilization has survived into modern times with its principal characteristics intact. Also and this makes it unique it retains a language more than 6,000 years old. This is undoubtedly the outcome of a series of happy coincidences but, first and foremost, it results from the Chinese system of writing: those fascinating, mysterious characters, each of which hides a snatch of history, literature, art and popular wisdom.

Never has the word calligraphy been so aptly used as here, even though it is still difficult for the Western eye to appreciate the full beauty and depth of this writing or to understand the aesthetic message contained in its lines. The nature of the written language and the use of the same instruments, brush and ink, has ensured that the writing of characters has formed an integral part of the history of Chinese painting.

Wáng Xi Zhi (321-379), the "calligrapher sage" who lived under the Eastern Jin (317-420), is regarded as the greatest master of all time and the model for all those wishing to become engaged in the art of character writing. His rich poetical and imaginative style is conveyed in his portrayal of writing as a real battle. In his work The Calligraphic Strategy of the Lady Wèi, he writes: "The sheet of paper is a battleground; the brush: the lances and swords; the ink: the mind, the commander-in-chief; ability and dexterity: the deputies; the composition: the strategy. By grasping the brush the outcome of the battle is decided: the strokes and lines are the commanders orders; the curves and returns are the mortal blows." An exciting battle, but fortunately a bloodless one: one of the few that mankind can enjoy and be proud of.

The first characters were incised, using wooden sticks, pointed stones, jade knives or bronze styli. These are the marks we find on ceramics, on bones, inside vases and on bronze artefacts. The graphic transformation of characters was caused by changes in the implements used for writing or the introduction of new writing surfaces such as wood, silk and paper. On a Shang bronze (16th-11th century B.C.) we find a design for a pen with a reservoir; it takes the form of a cup shaped container attached to one end of a hollow straw which deposited the colouring liquid on strips of bamboo. The result was a thick, uniform line. Around 213 B.C. widespread use appears to have been made of brushes with a fibrous tip suitable for writing on silk: these worked faster, but were still too rigid and gave a thick, square line.

During the same period a further advance was made by replacing the fibrous tip with one made of leather, which was softer and more flexible. It is to a general in the imperial army of the Qín dynasty (229-206 B.C.), however, that we owe a marked improvement in the quality of writing instruments. Méng Tián, who wielded the sword as skillfully as the brush, replaced the leather tip with a tuft of soft animal hairs. His intuitive innovation was linked to the discovery of a new writing material: paper. This quickly absorbed the water, making it possible to create lines of varying intensity. He maintained that the brush, with its very soft, pliable tip, could create every sort of effect when placed in the hands of a skilled calligrapher: everything from a thin, thread like line to a thick one; from a full, rich stroke to a broken, fading one; from a squared line to a rounded one with either a sharp or blunted point. This moment marked the birth of calligraphy, which now entered the history of Chinese painting and was treated with the same honour and dignity accorded to figurative works.

Apart from the instrument and the writing surface, another important element was India ink, in fact a Chinese discovery, obtained from soot, or lampblack, mixed into a paste with glue and perfumed with camphor and musk. Shaped into tablets or small sticks, it was decorated with figures or extracts from famous calligraphers written in gold characters. It is one of the "treasures of the literate," together with the brush, the paper and the "ink stone" (a type of Chinese ink pot). These stones were carefully selected, then carved and finely decorated, with two wells hollowed out in their surface: one to act as a container for water; the other, larger, in which to rub the ink tablet to produce a fine black powder. This would then be diluted with water. Using the best stones, and skillfully mixing the powder with water, it is possible to obtain the shades known to the Chinese as "the five shades of black."

The history and mythology of a script

Knots tied in lengths of vegetable fiber, which represented a sort of calendar, marked the first attempts by Chinese man to establish records. Later on, notches scored on wooden laths acted as a means of recording harvests and other events; later still, sticks, stones and bones were used to make marks on clay objects. The Neolithic village of Bànpo, more than 6,000 years old discovered in 1953 near Xian and the largest and most complete human settlement so far excavated represents one of the most important sources of information on ancient Chinese writing. Two types of signs appear on red clay pots found there: the simplest ones are probably numerals, while other, more complex ones indicate names of clans and tribes (see page 12).

These are the forerunners of the characters as they are known today, even though they anticipate pictographs by several millennia; the latter require a degree of skill and manual dexterity those early Neolithic Chinese appear not to have possessed. The development of Chinese characters can be loosely subdivided into four chronological stages: the primitive period (8000 3000 B.C.), during which man expressed himself first in conventional signs that had a mnemonic function and later in designs that reproduced the world around him: pictographs. The archaic period (3000 c. 1600 B.C.) includes the pre dynastic period and the Xià dynasty, during which there was a transition from pictographs to ideograms, from direct to indirect symbols, thus filling the gap left by early Chinese man when faced with abstract concepts. The historic period spanned 18 centuries beginning with the Shang or Yin dynasty and ending with the fall of the Eastern Hàn (A.D. 220) during which writing completed its evolution and took on its definitive form: the determinative characters and phonetics were born, the main styles were developed and form and meaning were established. Over the centuries that followed, the Chinese merely made use of what had already been invented and codified during the earlier period. Finally we come to the contemporary period, which began in 1949 with the founding of the Peoples Republic of China. This is an important age for the changes made to the writing and structure of characters, the result of a campaign to eradicate illiteracy. These modifications had three main aims: to simplify characters that were difficult but in common use; to achieve a common national pronunciation by means of the Putònghuà (common language); to be able to transcribe the characters in alphabetical letters in accordance with a system known as Pin yin, that is, combining the sounds with syllables, which gave uniformity to the earlier differences in transliteration. This programme of intensive "alphabetization" has clearly favoured a quantitative rather than qualitative knowledge of the written language, which is regarded as an inalienable part of the Chinese national heritage.

The mythological account is altogether more romantic and mysterious. This tells how the notion of progressing from knots tied in a piece of rope to drawings of words and ideas to a quicker and easier graphic sign belongs to the mythical Fú Xi, the first of the Five Emperors of the legendary period. Living 5,000 years ago, he is credited with the invention of rope, fishing and hunting nets, musical instruments and the eight trigrams. He taught man how to use fire to cook food and how to raise and tend livestock, becoming the protective deity of nomadic life. Legends clearly pay little heed to archaeology.

In a commentary to the Book of Changes (Yì Jing), one of the worlds oldest books, there is a passage that reads as follows: "When Fú Xi governed everything under the sky, he looked upward and admired the splendid designs in the heavens, and looking down he observed the structure of the earth. He noted the elegance of the shapes of birds and animals and the balanced variety of their territories. He studied his own body and the distant realities and afterwards invented the eight trigrams in order to be able to reveal the transformations of nature and understand the essence of things." In this way, it was alleged, characters were born.

But Fú Xi is not alone; Huáng Di, who lived 4,700 years ago, is also believed to have been the father of writing. The legendary Yellow Emperor is said to have been given the characters by a dragon that emerged from the waters of the Huáng Ghé, the Yellow River. Another legend attributes the invention of the characters to Cang Jié, a learned minister of the Yellow Emperor. He was struck by the tracks left by animals on the ground, particularly those of birds, whose claw marks gave him the idea for the lines that make up the characters. Two thousand years later, a style of writing was born known as niao zhuàn, bird character. Finally, there is talk of a third claimant, who was given the characters as a token of gratitude by a tortoise saved from drowning. He was the third of the Five Emperors, the Great Yu, founder of the Xià dynasty (21st 16th century B.C.), the same person who taught man how to channel water and cultivate the land, the patron of farming life.

Classification and radical characters

Learning how to recognize Chinese characters and how to write them correctly has never been easy. Ancient scribes often filled spaces with incorrect or even invented characters: such lexical monstrosities, the fruits of ignorance or fantasy, cause philologists considerable trouble.

In order to put a stop to this, the great emperor Qín ordered his prime minister Li Si to compile a catalogue of the characters to be used in official documents and literary works. And so the first Chinese dictionary was born, the San Chang, containing 3,300 characters, some of them so called "monster characters" (Ji zi), which were thus assured a place in history. For the first time, the shape and meaning of words were officially defined.

Three centuries later, the scholar Xú Shen composed the first carefully researched lexicon, complete with definitions and commentaries. Its 15 volumes, published in A.D. 121 under the name Shuo wen jie zi, extended and updated Li Sis dictionary. It was an imposing work that brought the number of characters up to 10,516, grouped under 540 radicals.

A further 1,600 years were to elapse before the appearance of another dictionary as innovative and important as Xú Shens work. Under the final imperial dynasty, the Qing (1644 1911), the last dictionary of the classical language was compiled. In 1717 the second emperor of the dynasty, Kang Xi (1661 1722), published the Kang Xi zi dian. This dictionary, which bears his name, contains 40,000 characters arranged under 214 radicals, less than half the number in Xú Shens lexicon.

Finally, in 1967, the Xinhua zi dian (Dictionary of New China) was published, a work that has been used as the basis for many bilingual dictionaries. The radicals were modified and some of them doubled, their number rising to 227; simplified characters were introduced to replace 2,252 others considered "difficult." Although this publication is by no means a literary work, and although many of its points are debatable, it nevertheless marks the first step toward a scientifically modern written language through the establishment of an up to date lexicon. It also marks the first use in transcription of Pin yin, the newest system of transliterating Chinese writing into alphabetical form, which has effectively superseded all earlier methods, the most common of which was the Wade Giles system.

The official classification, the most scholarly so far despite its understandable shortcomings will always be that of the Kang Xi period, which is the source of the 214 radicals illustrated in this volume.

Having made their first historical appearance in the Shuo wén, where they numbered 540, and having been reduced to 214 in the Kang Xi and then raised to 227 in modern dictionaries, these radicals hold the key to reading Chinese and give the phonetic compositions their meaning.

All the characters are grouped under their radicals. It is the radicals that allow us to locate characters in the dictionary because Chinese, not being an alphabetical language, does not permit the arrangement of words in any alphabetical order: in order to find a character you must first discover the radical from which it is composed. The progressive number that identifies a character refers back to the radical with a list of all its relevant composites. By counting all the strokes that occur in the character, excluding the radical, you will arrive at the subgroup that encompasses the same number of strokes and thence at the character you are seeking. It is not easy, but neither is it impossible.

Of the 214 radicals in the Kang Xi, 49 can be written in different ways. For some this is just a matter of slight modification, for others there is a simplified form of script and for one small group there exists a reduced form used in composite characters (see below). The radical therefore serves a dual purpose: it allows a character to be located in the dictionary and, normally, it indicates its meaning.

However, the authors decision to illustrate and explain the 214 radicals is not the outcome of any desire to educate his readers but rather to involve them in a game of wits, to lead them down the bizarre yet stimulating road that leads back to the roots of the Chinese language and so to introduce them to its spirit, its philosophy and its riches.

Styles of calligraphy

Although preserving the basic formal characteristics that allow us to grasp its meaning, every character can be written in a variety of ways. Its appearance is linked to the instrument with which it is written, to the material on which it is inscribed and, above all, to the technical ability and artistic sense of the individual calligrapher. Every Chinese knows that calligraphy is a key to reading the scribe; each character reveals not only the style but also the background, the skill, the mind and the passions of the person who produces it. There are styles with narrow, thick, regular, irregular, intense or light lines; others are squared, fine, elongated, horizontal, soft, stiff or sinuous. All this and more determines calligraphic style. Precisely because they are linked to the personality of the writer, many different styles of calligraphy have emerged over the centuries and still continue to develop today; they represent the individual touch, the artistic genius of certain men. Every Chinese calligrapher must be familiar with, and know how to write in, the six classic styles, aiming to achieve perfection in those which best suit his means and his talent (see below).

The Six Families

Nobody knows exactly how many Chinese characters there are. The most recent dictionary lists more than 48,000, but it is not a specialist dictionary and thus omits many classical, scientific and technical terms. Chinese is, after all, a living l...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAbbeville Press

- Publication date1987

- ISBN 10 0896597741

- ISBN 13 9780896597747

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages252

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0896597741

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_0896597741

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0896597741

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0896597741

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0896597741

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0896597741

CHINESE CALLIGRAPHY: FROM PICTOG

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.95. Seller Inventory # Q-0896597741

Chinese Calligraphy

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABE-1534102163644