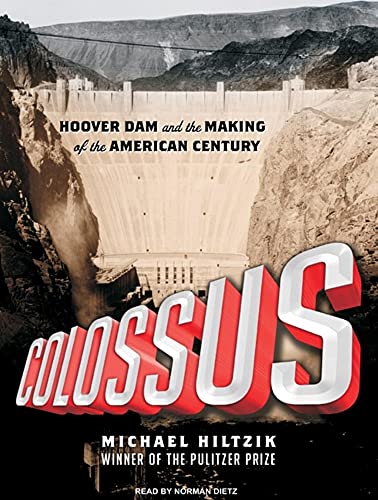

Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century

As breathtaking today as when it was completed, Hoover Dam ranks among America's greatest achievements. The story of its conception, design, and construction is the story of the United States at a unique moment in history: when facing both a global economic crisis and the implacable elements of nature, we prevailed.

The United States after Hoover Dam was a different country from the one that began to build it, going from the glorification of individual effort to the value of shared enterprise and communal support. The dam became the physical embodiment of this change. A remote regional construction project transformed from a Republican afterthought into a New Deal symbol of national pride.

Hoover Dam went on to shape not only the American West but the American century. Michael Hiltzik populates the epic tale of the dam's construction with larger-than-life characters, such as Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, William Mulholland, and the dam's egomaniacal architect, Frank Crowe. Shedding real light on a one-of-a-kind moment in twentieth-century American history, Hiltzik combines exhaustive research, trenchant observation, and a gift for unforgettable storytelling in a book that is bound to become a classic in its genre.

The United States after Hoover Dam was a different country from the one that began to build it, going from the glorification of individual effort to the value of shared enterprise and communal support. The dam became the physical embodiment of this change. A remote regional construction project transformed from a Republican afterthought into a New Deal symbol of national pride.

Hoover Dam went on to shape not only the American West but the American century. Michael Hiltzik populates the epic tale of the dam's construction with larger-than-life characters, such as Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, William Mulholland, and the dam's egomaniacal architect, Frank Crowe. Shedding real light on a one-of-a-kind moment in twentieth-century American history, Hiltzik combines exhaustive research, trenchant observation, and a gift for unforgettable storytelling in a book that is bound to become a classic in its genre.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Michael Hiltzik is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and the author of The Plot Against Social Security, Dealers of Lightning, and A Death in Kenya.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

The Journey of Death

By any customary measure, the Colorado River is an unremarkable stream. It does not rank as the longest river in North America, nor the widest, nor the most abundant. Its drainage basin of a quarter-million square miles barely falls within the ten largest in the United States, and much of it covers inaccessible range or desolate wasteland. Unlike the Mississippi, Hudson, and St. Lawrence, to name three great riparian thoroughfares of the continent, the Colorado has never been a significant bearer of commercial traffic.

Throughout history, what has set the Colorado River apart from all other waterways of the Western Hemisphere is its violent personality. The Colorado has always been best known for the scars it left on the landscape, among them the greatest of all natural works, the Grand Canyon, a testament to the river’s primordial origin and its compulsive energy. No river equaled its maniacal zeal for carving away the terrain in its path and carrying it downstream, sometimes as far as a thousand miles. No river matched its schizophrenic moods, which could swing in the course of a few hours from that of a meandering country stream to an insane torrent.

It is hardly surprising that from ancient times, the humans who coexisted with the Colorado depicted it not as a beneficent life-giving force but as a fiery red monster, a dragon or serpent beyond man’s ability to tame.

The basin’s first recorded inhabitants, the native tribespeople of the southern plains, had no option but to accommodate themselves to the river’s implacable temperament. They pastured their livestock on the grass that sprang up in the wake of its floods, planted crops on its rich alluvial deposits, imagined their gods and spirits housed within its labyrinthine canyons, assembled their myths and legends from the raw material of its natural mystery.

The American settlers of a later era, driven by the demands of commerce and dreams of wealth, were not so inclined to defer to nature’s unpredictable willfulness. From their earliest encounters with the river, they pondered how to corral it, divert it, drain it, and consume it. The California engineer Joseph Barlow Lippincott, dispatched to the river by the city of Los Angeles in 1912, pronounced it “an American Nile awaiting regulation”—to be best treated “in as intelligent and vigorous a manner as the British government has treated its great Egyptian prototype.”

Lippincott’s judgment reflected a new conservation policy then taking root in the United States. It was based on defining conservation not as protection or preservation but as exploitation. Woodrow Wilson’s interior secretary, Franklin K. Lane, laid out the new approach with striking directness. “Every tree is a challenge to us, and every pool of water and every foot of soil,” he proclaimed. “The mountains are our enemies. We must pierce them and make them serve. The sinful rivers we must curb.”

Lane’s successors answered his call to arms. Over the following decades, the U.S. government carried out an ambitious program to harness the sinful Colorado, working the river until the volume remaining to trickle into the sea scarcely merited an asterisk on a hydrological graph. The architects of this program couched their intentions in moral terms, as though they were not altering the natural order but restoring the watershed to a state of grace. “The Colorado River flows uselessly past the international desert which Nature intended for its bride,” wrote William Ellsworth Smythe, the most prominent water evangelist of his era, in 1900. “Some time the wedding of the waters to the soil will be celebrated, and the child of that union will be a new civilization.”

What first lured Europeans to the banks of the Colorado, however, was not its potential to nurture crops. It was gold. Or, more precisely, the mirage of gold.

The Spanish conquistadors, led by Hernân Cortes and Francisco Pizarro, had completed their plunder of the Inca and Aztec empires of the New World before the sixteenth century was three decades old. They had looted the Indians’ storehouses, exhausted their mines, and worked legions of slaves to death. Yet their appetite for gold, silver, and gemstones remained unquenched.

Fortuitously, hints of new treasures soon emerged from the uncharted north, reenergizing the Spanish quest. In the mid-1530s, adventurers returned from Indian imprisonment in the Sonoran Desert—present-day New Mexico and Arizona—laden with news of a land called Cibola, where stood seven magnificent cities in which (according to the yarn one traveler spun for his relatives) “the women wore strands of gold and the men golden waistbands” and the palace walls were encrusted with emeralds.

Lured by this vision of wealth, the conquistadors probed along the Sea of Cortez (the Gulf of California) until they encountered, inevitably, the Colorado delta. The first advance parties were driven back by the ferocious tides at the confluence of the river and gulf. Finally, in 1539, a ship under the tenacious command of Captain Hernando de Alarcón managed to sail upriver about 150 miles, penetrating well into Sonora. He was shortly followed by an immense force under the command of General Francisco Vâsquez de Coronado, dispatched to explore the beckoning golden empire by land.

Coronado’s scouts were soon filling in the blank maps of the Southwest. They renamed the Colorado the Rio del Tison, or Firebrand River—not because of its willfulness, but for the torches the local Indians bore on their travels—and they came upon the Grand Canyon, reporting the immense natural formation with appropriate wonderment.

But their quest for gold failed. A pueblo city that scouts had described as ringed with gilded ramparts proved to be built of mere mud and clay, which happened to glimmer deceptively in the setting sun. The other majestic cities of Cibola remained as elusive as phantasms. For two more years

Coronado searched for gold, finally returning home empty-handed and deeply in debt.

Yet there was gold in the north, just not where he had been looking for it. Another three centuries would pass before its discovery would attract white Americans in great numbers back to what had long since been written off as a hopelessly unprepossessing territory. The Gold Rush of 1849 would draw ninety thousand fortune seekers, known as Forty-niners or Argonauts, to ford the Colorado River—part of a migration of men, women, and families that has been called “the largest single western movement in the nation’s history.”

The frenzy began with an unassuming item on an inside page of the San Francisco Californian of March 15, 1848, headlined, “GOLD MINE FOUND.” It did not fully take root in the national consciousness until nine months later, when President James K. Polk gave the federal government’s imprimatur to the discovery at Sutter’s Mill. As an expansionist, Polk made no effort to downplay a discovery likely to encourage new settlement in an underpopulated region. Instead, he reported in his annual message to Congress on December 5 that “the explorations already made warrant the belief that the supply is very large.”

Some 300,000 Argonauts struck out for the West, a third of them taking what became known as the southern routes—overland byways converging at Yuma, Arizona, where the Gila River joined the Colorado, and continuing along one or another waterless trail, or jornada, toward the Pacific coast. These trails acquired a vicious reputation. One in particular, a desert crossing paralleling the Rio Grande in New Mexico, bore a label that presently was applied to the entire unspeakably harsh road west. It was known in Spanish as la jornada de la muerte; in English as “the journey of death.”

Perils of every variety confronted travelers on the jornada: disease, brigands, hostile tribes, and the daunting terrain itself. Not even the best-out-fitted expeditions were immune. This was shown by the dire experience of John Woodhouse Audubon, the renowned naturalist’s younger son, who left New York for the Texas coast and points west with a party of eighty, backed by what was regarded as lavish capital of $27,000.

On the day of his departure, Audubon was a youthful thirty-six, “tall, strong and alert,” in the words of his daughter Maria. When he returned home a year later he was broken, “worn out in body and spirit” by his travails on the Jornada and the loss at sea of all his sketches and most of his notebooks.

The first blow to strike Audubon’s company had been cholera, which killed five members within days of their landing in Texas and reduced a dozen others to dehydrated wraiths. The survivors pressed on, Audubon collecting botanical specimens and sketching wildlife in his father’s style. In mid-October he and his remaining companions reached the junction of the Gila and the Colorado, which he dismissed as merely a “muddy stream.” Crossing to the opposite bank and clambering up a sand dune, he perceived a further omen of the dismal prospects facing the expedition. He was perched upon a desert ridge that belonged to the “walking hills” of California, a natural barrier that would obstruct men’s activities in the region for the next half-century. “There was not a tree to be seen, nor the least sign of vegetation, and the sun pouring down on us made our journey seem twice the length it really was.”

The next day Audubon’s group came upon a chain of fetid lagoons, where they deduced the fate of their numberless predecessors from the detritus scattered on the ground. “Truly here was a scene of desolation,” he wrote.

Broken wagons, dead shriveled up cattle, horses and mules as well, lay baking in the sun, around the dried-up wells that had been opened, in the hopes of getting water. Not a blade of grass or green thing of any kind relieved the monotony of the parched, ash-colored earth, and the most melancholy scene presented itself that I have seen since I left the Rio Grande.

They could hardly have suspected, slogging through the vacant wastes and slaking their thirst from pools of water described by a fellow traveler as “a tincture of bluelick, iodides of sulphur, Epsom salts, and a strong decoction of decomposed mule flesh,” that they were crossing the grounds of a future paradise. The introduction of fresh water to the Imperial Valley and the dam that would impound it lay decades in the future. But the Argonauts’ journeys marked a vital step in the process. The Gold Rush awoke official Washington to the military and economic significance of America’s western territories and to the necessity of acquiring firsthand testimony about what lay between the frontier and the Pacific coast.

One of the prime movers of what became known as the Great Reconnaissance was President Franklin Pierce’s secretary of war, Jefferson Davis.

The desert held a peculiar fascination for Jeff Davis. As a U.S. senator, he had risked public ridicule by proposing to deploy camels in the Southwest as a military experiment. Upon joining the cabinet in 1853, he put his plan into action by importing fifty of the animals for his department, but the program collapsed four years later, following his and President Pierce’s departure from power.

A more enduring mark was left by the survey Davis commissioned to identify a Southwestern route for an intercontinental railroad. The reports from his five survey parties later published in twelve majestic volumes-America’s most important exploratory record since Lewis and Clark—contained a wealth of information about the vast region’s topography, geology, wildlife, and natural history.

Attached to the survey was William Phipps Blake, a young geologist from a prominent Eastern family. Blake’s party failed to discern a suitable railroad route, but he did stumble upon a remarkable geologic feature in the trackless desert. His first clue that he had found something extraordinary came on November 17, 1853, when from the edge of a windswept ridge in the San Bernardino Mountains (not far from the site of modern Palm Springs) he noticed “a discoloration of the rocks extending for a long distance in a horizontal line on the side of the mountains.”

With great excitement, Blake worked his way down the gradient. From the valley floor the line “could be traced along the mountain sides, following all the angles and sinuosities of the ridges for many miles—always preserving its horizontality—sometimes being high up above the plain, and again intersecting long and high slopes of gravel and sand; on such places a beach-line could be read.”

The conclusion was inescapable: he was standing in the dry bed of an immense ancient sea, and the white line was its high water mark.

Blake named the sea Lake Cohuilla, after the local Indian tribe. The white deposit, he determined, was composed of the fossilized shells of freshwater animals. His barometer told him that his location measured at least one hundred feet below sea level. From the Indians he learned that the valley served as the traditional locus of their own flood legend, “a tradition they have of a great water (agua grande) which covered the whole valley and was filled with fine fish. . . . Their fathers lived in the mountains and used to come down to the lake to fish and hunt. The water gradually subsided ‘poco,’ ‘poco,’ (little by little,) and their villages were moved down from the mountains, into the valley it had left. They also said that the waters once returned very suddenly and overwhelmed many of their people and drove the rest back to the mountains.”

The desert was shaped like an oblong bowl rising from a central depression, or “sink,” about one hundred miles west of the Colorado River and deeper at its lowest point than Death Valley. The region’s rainfall of less than three inches a year, the continent’s most meager, had created over the eons a terrain as empty as the Arabian wastes. Where there was any vegetation at all, it was of the lowliest variety, resinous greasewood and creosote whose roots clung like talons to the sun-hardened earth.

Yet Blake was not fooled by the apparent lifelessness of the cracked and sere clay veneer. “The alluvial soil of the Desert is capable of sustaining a vigorous vegetation,” he reported. “If a supply of water could be obtained for irrigation, it is probable that the greater part of the Desert could be made to yield crops of almost any kind.”

The desert was in fact a deposit of rich soil eroded by the Colorado River from the basin upstream and transported south at the rate of 160 million tons a year. Working on millennial time, the silt filled in the shallow headwaters of the Gulf of California, shifting its shore 150 miles southward. This process turned the gulf’s northernmost arm into the landlocked lake later known as the Salton Sea. As the lake slowly evaporated, it left behind a crust of mineral salt and calcified shells, the remnants of which Blake had spotted.

Meanwhile, the river built up its bed with its own silt deposits year after year, like a train laying its own tracks. Eventually the river would be flowing within parallel levees elevated high above the desert floor. In time the levees would become unstable, their walls would collapse, and the stream, freed of its constraints, would inundate the desert basin, recharging the inland sea. Centuries would pass, a new accumulation of silt would stopper the errant flow, and the river would return to its old delta, resuming its journey to the gulf. Again the sea would evaporate, again the river would build up and tear down its levees, and again the sea would fill up, in a never-ending cycle.

How many such oscillations took place over the ag...

By any customary measure, the Colorado River is an unremarkable stream. It does not rank as the longest river in North America, nor the widest, nor the most abundant. Its drainage basin of a quarter-million square miles barely falls within the ten largest in the United States, and much of it covers inaccessible range or desolate wasteland. Unlike the Mississippi, Hudson, and St. Lawrence, to name three great riparian thoroughfares of the continent, the Colorado has never been a significant bearer of commercial traffic.

Throughout history, what has set the Colorado River apart from all other waterways of the Western Hemisphere is its violent personality. The Colorado has always been best known for the scars it left on the landscape, among them the greatest of all natural works, the Grand Canyon, a testament to the river’s primordial origin and its compulsive energy. No river equaled its maniacal zeal for carving away the terrain in its path and carrying it downstream, sometimes as far as a thousand miles. No river matched its schizophrenic moods, which could swing in the course of a few hours from that of a meandering country stream to an insane torrent.

It is hardly surprising that from ancient times, the humans who coexisted with the Colorado depicted it not as a beneficent life-giving force but as a fiery red monster, a dragon or serpent beyond man’s ability to tame.

The basin’s first recorded inhabitants, the native tribespeople of the southern plains, had no option but to accommodate themselves to the river’s implacable temperament. They pastured their livestock on the grass that sprang up in the wake of its floods, planted crops on its rich alluvial deposits, imagined their gods and spirits housed within its labyrinthine canyons, assembled their myths and legends from the raw material of its natural mystery.

The American settlers of a later era, driven by the demands of commerce and dreams of wealth, were not so inclined to defer to nature’s unpredictable willfulness. From their earliest encounters with the river, they pondered how to corral it, divert it, drain it, and consume it. The California engineer Joseph Barlow Lippincott, dispatched to the river by the city of Los Angeles in 1912, pronounced it “an American Nile awaiting regulation”—to be best treated “in as intelligent and vigorous a manner as the British government has treated its great Egyptian prototype.”

Lippincott’s judgment reflected a new conservation policy then taking root in the United States. It was based on defining conservation not as protection or preservation but as exploitation. Woodrow Wilson’s interior secretary, Franklin K. Lane, laid out the new approach with striking directness. “Every tree is a challenge to us, and every pool of water and every foot of soil,” he proclaimed. “The mountains are our enemies. We must pierce them and make them serve. The sinful rivers we must curb.”

Lane’s successors answered his call to arms. Over the following decades, the U.S. government carried out an ambitious program to harness the sinful Colorado, working the river until the volume remaining to trickle into the sea scarcely merited an asterisk on a hydrological graph. The architects of this program couched their intentions in moral terms, as though they were not altering the natural order but restoring the watershed to a state of grace. “The Colorado River flows uselessly past the international desert which Nature intended for its bride,” wrote William Ellsworth Smythe, the most prominent water evangelist of his era, in 1900. “Some time the wedding of the waters to the soil will be celebrated, and the child of that union will be a new civilization.”

What first lured Europeans to the banks of the Colorado, however, was not its potential to nurture crops. It was gold. Or, more precisely, the mirage of gold.

The Spanish conquistadors, led by Hernân Cortes and Francisco Pizarro, had completed their plunder of the Inca and Aztec empires of the New World before the sixteenth century was three decades old. They had looted the Indians’ storehouses, exhausted their mines, and worked legions of slaves to death. Yet their appetite for gold, silver, and gemstones remained unquenched.

Fortuitously, hints of new treasures soon emerged from the uncharted north, reenergizing the Spanish quest. In the mid-1530s, adventurers returned from Indian imprisonment in the Sonoran Desert—present-day New Mexico and Arizona—laden with news of a land called Cibola, where stood seven magnificent cities in which (according to the yarn one traveler spun for his relatives) “the women wore strands of gold and the men golden waistbands” and the palace walls were encrusted with emeralds.

Lured by this vision of wealth, the conquistadors probed along the Sea of Cortez (the Gulf of California) until they encountered, inevitably, the Colorado delta. The first advance parties were driven back by the ferocious tides at the confluence of the river and gulf. Finally, in 1539, a ship under the tenacious command of Captain Hernando de Alarcón managed to sail upriver about 150 miles, penetrating well into Sonora. He was shortly followed by an immense force under the command of General Francisco Vâsquez de Coronado, dispatched to explore the beckoning golden empire by land.

Coronado’s scouts were soon filling in the blank maps of the Southwest. They renamed the Colorado the Rio del Tison, or Firebrand River—not because of its willfulness, but for the torches the local Indians bore on their travels—and they came upon the Grand Canyon, reporting the immense natural formation with appropriate wonderment.

But their quest for gold failed. A pueblo city that scouts had described as ringed with gilded ramparts proved to be built of mere mud and clay, which happened to glimmer deceptively in the setting sun. The other majestic cities of Cibola remained as elusive as phantasms. For two more years

Coronado searched for gold, finally returning home empty-handed and deeply in debt.

Yet there was gold in the north, just not where he had been looking for it. Another three centuries would pass before its discovery would attract white Americans in great numbers back to what had long since been written off as a hopelessly unprepossessing territory. The Gold Rush of 1849 would draw ninety thousand fortune seekers, known as Forty-niners or Argonauts, to ford the Colorado River—part of a migration of men, women, and families that has been called “the largest single western movement in the nation’s history.”

The frenzy began with an unassuming item on an inside page of the San Francisco Californian of March 15, 1848, headlined, “GOLD MINE FOUND.” It did not fully take root in the national consciousness until nine months later, when President James K. Polk gave the federal government’s imprimatur to the discovery at Sutter’s Mill. As an expansionist, Polk made no effort to downplay a discovery likely to encourage new settlement in an underpopulated region. Instead, he reported in his annual message to Congress on December 5 that “the explorations already made warrant the belief that the supply is very large.”

Some 300,000 Argonauts struck out for the West, a third of them taking what became known as the southern routes—overland byways converging at Yuma, Arizona, where the Gila River joined the Colorado, and continuing along one or another waterless trail, or jornada, toward the Pacific coast. These trails acquired a vicious reputation. One in particular, a desert crossing paralleling the Rio Grande in New Mexico, bore a label that presently was applied to the entire unspeakably harsh road west. It was known in Spanish as la jornada de la muerte; in English as “the journey of death.”

Perils of every variety confronted travelers on the jornada: disease, brigands, hostile tribes, and the daunting terrain itself. Not even the best-out-fitted expeditions were immune. This was shown by the dire experience of John Woodhouse Audubon, the renowned naturalist’s younger son, who left New York for the Texas coast and points west with a party of eighty, backed by what was regarded as lavish capital of $27,000.

On the day of his departure, Audubon was a youthful thirty-six, “tall, strong and alert,” in the words of his daughter Maria. When he returned home a year later he was broken, “worn out in body and spirit” by his travails on the Jornada and the loss at sea of all his sketches and most of his notebooks.

The first blow to strike Audubon’s company had been cholera, which killed five members within days of their landing in Texas and reduced a dozen others to dehydrated wraiths. The survivors pressed on, Audubon collecting botanical specimens and sketching wildlife in his father’s style. In mid-October he and his remaining companions reached the junction of the Gila and the Colorado, which he dismissed as merely a “muddy stream.” Crossing to the opposite bank and clambering up a sand dune, he perceived a further omen of the dismal prospects facing the expedition. He was perched upon a desert ridge that belonged to the “walking hills” of California, a natural barrier that would obstruct men’s activities in the region for the next half-century. “There was not a tree to be seen, nor the least sign of vegetation, and the sun pouring down on us made our journey seem twice the length it really was.”

The next day Audubon’s group came upon a chain of fetid lagoons, where they deduced the fate of their numberless predecessors from the detritus scattered on the ground. “Truly here was a scene of desolation,” he wrote.

Broken wagons, dead shriveled up cattle, horses and mules as well, lay baking in the sun, around the dried-up wells that had been opened, in the hopes of getting water. Not a blade of grass or green thing of any kind relieved the monotony of the parched, ash-colored earth, and the most melancholy scene presented itself that I have seen since I left the Rio Grande.

They could hardly have suspected, slogging through the vacant wastes and slaking their thirst from pools of water described by a fellow traveler as “a tincture of bluelick, iodides of sulphur, Epsom salts, and a strong decoction of decomposed mule flesh,” that they were crossing the grounds of a future paradise. The introduction of fresh water to the Imperial Valley and the dam that would impound it lay decades in the future. But the Argonauts’ journeys marked a vital step in the process. The Gold Rush awoke official Washington to the military and economic significance of America’s western territories and to the necessity of acquiring firsthand testimony about what lay between the frontier and the Pacific coast.

One of the prime movers of what became known as the Great Reconnaissance was President Franklin Pierce’s secretary of war, Jefferson Davis.

The desert held a peculiar fascination for Jeff Davis. As a U.S. senator, he had risked public ridicule by proposing to deploy camels in the Southwest as a military experiment. Upon joining the cabinet in 1853, he put his plan into action by importing fifty of the animals for his department, but the program collapsed four years later, following his and President Pierce’s departure from power.

A more enduring mark was left by the survey Davis commissioned to identify a Southwestern route for an intercontinental railroad. The reports from his five survey parties later published in twelve majestic volumes-America’s most important exploratory record since Lewis and Clark—contained a wealth of information about the vast region’s topography, geology, wildlife, and natural history.

Attached to the survey was William Phipps Blake, a young geologist from a prominent Eastern family. Blake’s party failed to discern a suitable railroad route, but he did stumble upon a remarkable geologic feature in the trackless desert. His first clue that he had found something extraordinary came on November 17, 1853, when from the edge of a windswept ridge in the San Bernardino Mountains (not far from the site of modern Palm Springs) he noticed “a discoloration of the rocks extending for a long distance in a horizontal line on the side of the mountains.”

With great excitement, Blake worked his way down the gradient. From the valley floor the line “could be traced along the mountain sides, following all the angles and sinuosities of the ridges for many miles—always preserving its horizontality—sometimes being high up above the plain, and again intersecting long and high slopes of gravel and sand; on such places a beach-line could be read.”

The conclusion was inescapable: he was standing in the dry bed of an immense ancient sea, and the white line was its high water mark.

Blake named the sea Lake Cohuilla, after the local Indian tribe. The white deposit, he determined, was composed of the fossilized shells of freshwater animals. His barometer told him that his location measured at least one hundred feet below sea level. From the Indians he learned that the valley served as the traditional locus of their own flood legend, “a tradition they have of a great water (agua grande) which covered the whole valley and was filled with fine fish. . . . Their fathers lived in the mountains and used to come down to the lake to fish and hunt. The water gradually subsided ‘poco,’ ‘poco,’ (little by little,) and their villages were moved down from the mountains, into the valley it had left. They also said that the waters once returned very suddenly and overwhelmed many of their people and drove the rest back to the mountains.”

The desert was shaped like an oblong bowl rising from a central depression, or “sink,” about one hundred miles west of the Colorado River and deeper at its lowest point than Death Valley. The region’s rainfall of less than three inches a year, the continent’s most meager, had created over the eons a terrain as empty as the Arabian wastes. Where there was any vegetation at all, it was of the lowliest variety, resinous greasewood and creosote whose roots clung like talons to the sun-hardened earth.

Yet Blake was not fooled by the apparent lifelessness of the cracked and sere clay veneer. “The alluvial soil of the Desert is capable of sustaining a vigorous vegetation,” he reported. “If a supply of water could be obtained for irrigation, it is probable that the greater part of the Desert could be made to yield crops of almost any kind.”

The desert was in fact a deposit of rich soil eroded by the Colorado River from the basin upstream and transported south at the rate of 160 million tons a year. Working on millennial time, the silt filled in the shallow headwaters of the Gulf of California, shifting its shore 150 miles southward. This process turned the gulf’s northernmost arm into the landlocked lake later known as the Salton Sea. As the lake slowly evaporated, it left behind a crust of mineral salt and calcified shells, the remnants of which Blake had spotted.

Meanwhile, the river built up its bed with its own silt deposits year after year, like a train laying its own tracks. Eventually the river would be flowing within parallel levees elevated high above the desert floor. In time the levees would become unstable, their walls would collapse, and the stream, freed of its constraints, would inundate the desert basin, recharging the inland sea. Centuries would pass, a new accumulation of silt would stopper the errant flow, and the river would return to its old delta, resuming its journey to the gulf. Again the sea would evaporate, again the river would build up and tear down its levees, and again the sea would fill up, in a never-ending cycle.

How many such oscillations took place over the ag...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTantor Audio

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 140014678X

- ISBN 13 9781400146789

- BindingAudio CD

- Number of pages19

- Rating

US$ 46.00

Shipping:

US$ 3.75

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century

Seller:

Rating

Book Description audioCD. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_399226526

Buy Used

US$ 46.00

Convert currency