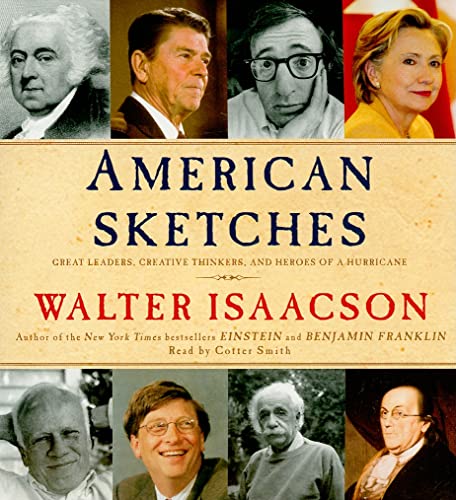

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

INTRODUCTION

My So-called Writing Life

On the Bogue Falaya with Walker Percy,

photographed by Jill Krementz

I was once asked to contribute an essay to the Washington Post for a page called “The Writing Life.” This caused me some consternation. A little secret of many nonfiction writers like myself—especially those of us who spring from journalism—is that we don’t quite think of ourselves as true writers, at least not of the sort who get called to reflect upon “the writing life.” At the time, my daughter, with all the wisdom and literary certitude that flowed from being a thirteen-year-old aspiring novelist, pointed out that I was not a “real writer” at all. I was merely, she said, a journalist and biographer.

To that I plead guilty. During one of his Middle East shuttle missions in 1974, Henry Kissinger ruminated, to those on his plane, about such leaders as Anwar Sadat and Golda Meir. “As a professor, I tended to think of history as run by impersonal forces,” he said. “But when you see it in practice, you see the difference personalities make.” I have always been one of those who feel that history is shaped as much by people as by impersonal forces. That’s why I liked being a journalist, and that’s why I became a biographer. As a result, the pieces in this collection are about people—how their minds work, what makes them creative, how they rippled the surface of history.

For many years I worked at Time magazine, whose cofounder, Henry Luce, had a simple injunction: Tell the history of our time through the people who make it. He almost always put a person (rather than a topic or an event) on the cover, a practice I tried to follow when I became editor. I would do so even more religiously if I had it to do over again. When highbrow critics accused Time of practicing personality journalism, Luce replied that Time did not invent the genre, the Bible did. That’s the way we have always conveyed lessons, values, and history: through the tales of people.

In particular, I have been interested in creative people. By creative people I don’t mean those who are merely smart. As a journalist, I discovered that there are a lot of smart people in this world. Indeed, they are a dime a dozen, and often they don’t amount to much. What makes someone special is imagination or creativity, the ability to make a mental leap and see things differently. In 1905, for example, the most knowledgeable physicists of Europe were trying to explain why a light wave always appeared to travel at the same speed no matter how fast you were moving relative to it. It took a third-class patent clerk in Bern, Switzerland, to make the creative leap, based only on thought experiments he imagined in his head. The speed of light remains constant, he said, but time varies depending on your state of motion. As Albert Einstein later noted, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

The first real writer I ever met was Walker Percy, the Louisiana novelist whose wry philosophical depth and lightly worn grace still awe me when I revisit my well-thumbed copies of The Moviegoer and The Last Gentleman. He lived on the Bogue Falaya, a bayou-like, lazy river across Lake Pontchartrain from my hometown of New Orleans. My friend Thomas was his nephew, and thus he became “Uncle Walker” to all of us kids who used to go up there to fish, capture sunning turtles, water-ski, and flirt with his daughter Ann. It was not quite clear what Uncle Walker did. He had trained as a doctor, but he never practiced. Instead, he worked at home all day. Ann said he was a writer, but it was not until after his first novel, The Moviegoer, gained recognition that it dawned on me that writing was something you could do for a living, just like being a doctor or a fisherman or an engineer.

He was a kindly gentleman, whose placid face seemed to know despair but whose eyes nevertheless often smiled. I began to spend more time with him, grilling him about what it was like to be a writer and reading the unpublished essays he showed me, while he sipped bourbon and seemed amused by my earnestness. His novels, I eventually noticed, carried philosophical, indeed religious, messages. But when I tried to get him to expound upon them, he would smile and demur. There are, he told me, two types of people who come out of Louisiana: preachers and story-tellers. It was better to be a storyteller.

That, too, became one of my guideposts as a writer. I was never cut out to be a pundit or a preacher. Although I had many opinions, I was never quite sure I agreed with them all. Just as the Bible shows us the power of conveying lessons through people, it also shows the glory of narrative—chronological storytelling—for that purpose. After all, it’s got one of the best ledes ever: “In the beginning . . .” The parables and narratives and tales in the Bible always seemed more compelling than the parts that tried to decree a litany of rules.

My parents were very literate in that proudly middlebrow and middle-class manner of the 1950s, which meant that they subscribed to Time and Saturday Review, were members of the Book-of-the-Month Club, read books by Mortimer Adler and John Gunther, and purchased a copy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica as soon as they thought that my brother and I were old enough to benefit from it. The fact that we lived in the heart of New Orleans added an exotic overlay. Then as now, it had a magical mix of quirky souls, many with artistic talents or at least pretensions. As the various tribes of the town rubbed up against each other, it produced sparks and some friction and a lot of joyful exchange, all ingredients for a creative culture. I liked jazz, tried my hand at clarinet, and spent time in the clubs that featured the likes of reedmen George Lewis and Willie Humphrey. After I discovered that one could be a writer for a living, I began frequenting the French Quarter haunts of William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams and sitting at a corner table of the Napoleon House on Chartres Street keeping a journal.

Fortunately, I was rescued from some of these pretensions by journalism. While in high school, I got a summer job at the States-Item, the feistier afternoon sibling of the Times-Picayune. I was assigned the 5 a.m. beat at police headquarters, and on my first day I found myself covering that most awful of stories, the murder of a young child. When I phoned in my report to the chief of the rewrite desk, Billy Rainey, he started barking questions: What did the parents say the kid was like? Did I ask them for any baby pictures of him? I was aghast. I explained that they were grieving and that I didn’t want to intrude. Go knock on the door and talk to them, Rainey ordered.

To my surprise, they invited me in. They pulled out photo albums. They told me stories as they wiped their tears. They wanted people to know. They wanted to talk. It’s another basic lesson I learned: The key to journalism is that people like to talk. At one point the mother touched me on the knee and said, “I hope you don’t mind me telling you all this.”

Almost twenty-five years later, I recalled that moment in the most unlikely circumstance. Woody Allen had been hit by the furor over the revelation that he was dating Soon-Yi Previn, the adopted daughter of his estranged consort, Mia Farrow. He invited me to come over to his apartment so that he could explain himself. It was just the two of us, and as soon as I opened my notebook, it became clear how much he wanted to talk. At one point, when I asked if he thought there was anything wrong with this set of relationships, he replied in a way destined to get him into the quotation books: “The heart wants what it wants.” After more than an hour, he leaned over and said, “I hope you don’t mind me telling you all this.” I thought, as his psychiatrist might have, No, I don’t mind. This is what I do for a living. I get paid to do it—amazingly enough.

When I went north to Harvard, I drove up with cases of Dixie beer piled in my beat-up Chevy Camaro, so that I could play the role of a southern boy, and I reread Absalom, Absalom and The Sound and the Fury, so that I could channel Quentin Compson while avoiding his fate. The most embarrassing piece I have ever written, which I fear is saying a lot, was a review of a biography of Faulkner for the Harvard Crimson that I attempted to write in Faulkner’s style. (No, it’s not included in this collection.) Not surprisingly, I was never asked to join the Crimson, but I did join the Lampoon, the humor magazine. Back then the Lampoon specialized in producing parodies, such as one of Cosmopolitan that had a fake foldout of a nude Henry Kissinger. It was thus that I learned, though only moderately well, another lesson that is useful when traveling in the realms of gold: that poking fun at the pretensions of the elite is more edifying than imitating them. I also began, for no particular reason, to gather string and write a chronicle of an obscure plantation owner, then no longer alive, named Weeks Hall, who had, earlier in the century, invited a wide variety of literary figures and creative artists to be houseguests at his home, which he called Shadows-on-the-Teche. From that I learned the joys of unearthing tales about interesting and creative people.

During the summers, I tended to come back home to New Orleans to work for the newspaper. I liked to think that I had the ability to drive into any small town and, within a day, meet enough new people that I would find a really good story. I pushed myself to practice that every now and then, with mixed success. If I were hiring young journalists now, that would be my test: I would pull out a map, pick out a small town at random, and ask them to go there and send me back a good story in forty-eight hours.

On one such outing through southern Louisiana, I wrote a set of articles on the life of the sharecroppers on the sugarcane plantations along Bayou LaFourche. The pieces showed the effects of my having read James Agee once too often, in that they tried too hard to be lyrical and literary, but they did help me get an even more interesting job the following summer. Harry Evans, who is now well known as an author and a historian, was then the hot, young, crusading editor of the Sunday Times of London. He gave a talk in which he lamented that America was no longer producing as many literary journalists in the mold of Agee. Without even a pretense of humility, I put together a packet of my sharecropper pieces and sent them off to him in London, asking for a summer job. I heard nothing, promptly forgot about my impertinent request, and thus was a bit baffled when months later a telegram arrived at my dorm (an occurrence almost as unusual then as it would be today), saying: will hire for limited term as thomson scholar. It was signed by someone I had never heard of, but I soon realized it was an offer from the Sunday Times. The “Thomson scholar” bit was because Harry needed a way to get around the unions in hiring someone like me, so he made up a fellowship and named it after the paper’s then-owner, Lord Thomson. I scraped up the money to buy a cheap ticket on Icelandair to London.

It was the summer of 1973, and the Watergate scandal was unfolding. Harry had created an investigative unit known as the Insight Team, and he put me on it under the mistaken impression that, since I was an American, I bore some resemblance to Woodward and Bernstein. My first big assignment was to go up to Dundee, Scotland, where the mayor, quaintly known as the Lord Provost, was suspected of having Nixonian tendencies. When I arrived at the airport, I cockily presented my Sunday Times press credential at the car counter only to be told that I was not old enough to rent one. Too embarrassed to tell my editors, I hitchhiked to my hotel.

Over the next few days, I was able to meet a lot of local characters and get them to talk. I pieced together a tangled web involving secret land purchases combined with nefarious adjustments to zoning laws. The article I wrote so baffled and unnerved my editors that they sent in reinforcements in the person of the most amazing journalist I have ever known, David Blundy. He was wild-eyed, boisterous, thrill-seeking, conspiratorial, and so excessively lanky that he looked like an animated cartoon character. One night when we returned to the hotel, the desk clerk mentioned that someone was in our room. David uncoiled himself into full alert mode, assuming that it must be some thug hired by the Lord Provost, and barked to me that I should take the elevator and he would take the stairs. The point of this eluded me, but I did as I was told. We arrived at the sixth floor at the same time. David flung open our door and, since he was a chain-smoker, immediately collapsed on the floor wheezing from his race up six flights of stairs. The interloper turned out to be a television repairman who scurried out of the room leaving various parts strewn on our floor.

I subsequently partnered with David on stories involving the troubles in Northern Ireland, Morocco’s war for the Spanish Sahara, and a ring of traders violating the sanctions against Rhodesia. He was exhilarated by danger. Once in Belfast he insisted that we go cover a demonstration, when I was quite content to stay at the bar of the Europa Hotel. He showed me that even though the street clashes might seem violent and bloody on television, just a half block away things were calm and safe. Journalism required an eagerness to get up and go places. While we were out, a bomb went off at the Europa Hotel. Blundy insisted that this should serve as a lesson for me. I agreed. But when he was killed a few years later by a sniper’s bullet in El Salvador, I gave up trying to fathom the meaning of the lesson he wanted me to learn.

At the Sunday Times, I learned that I was not cut out to be a Woodward or a Bernstein. I tended to like people too much to relish investigating them. Perhaps that’s the flip side of finding it easy to meet strangers and get them to talk. For example, one week I was sent to cover a fire at an amusement center, known as Summerland, on the Isle of Man, in which fifty people had died because of chained exit doors and other lapses. I ended up meeting Sir Charles Forte, the chief executive of the company that owned the park. He was very open, indeed vulnerable, as he discussed the mistakes that had led to the tragedy. It made for a good story, but it could have made for a really great story if I hadn’t decided to downplay some of what he told me. My instinct to be sympathetic got the better of my instincts as a journalist.

I learned from Harry Evans’s example that it was possible to be crusading and investigative while also retaining access to the people you cover. With his engaging manner and skeptical curiosity, he could be both an outsider (he was from Manchester) and an insider (he was knighted), as the occasion warranted. Every now and then, this lesson would be reinforced for me. For example, my first week covering the 1980 presidential campaign of Ronald Reagan for Time, I wrote a piece that looked at the facts he used in his stump speech, ranging from taxation levels to how trees caused pollution, and declared many to be dubious. I thought I would be shunned by the campaign staff on the plane the following week. Instead, I was invited to the front to ride with the candidate. There’s a phenomenon common to many people in public life....

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster Audio

- Publication date2009

- ISBN 10 1442304073

- ISBN 13 9781442304079

- BindingAudio CD

- Number of pages6

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 2.64

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

American Sketches : Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 7685637-n

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane by Isaacson, Walter [Audio CD ]

Book Description Audio Book (CD). Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781442304079

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1442304073

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1442304073

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1442304073

American Sketches : Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 7685637-n

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1442304073

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1442304073

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.33. Seller Inventory # Q-1442304073

American Sketches: Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers, and Heroes of a Hurricane

Book Description Audio CD. Condition: Brand New. abridged edition. 6 pages. 5.75x5.00x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 1442304073