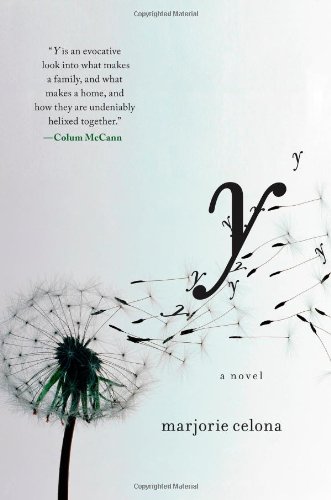

Y: A Novel - Hardcover

“Y. That perfect letter. The wishbone, fork in the road, empty wineglass. The question we ask over and over. Why? . . . My life begins at the Y.” So opens Marjorie Celona’s highly acclaimed and exquisitely rendered debut about a wise-beyond-her-years foster child abandoned as a newborn on the doorstep of the local YMCA. Swaddled in a dirty gray sweatshirt with nothing but a Swiss Army knife tucked between her feet, little Shannon is discovered by a man who catches only a glimpse of her troubled mother as she disappears from view. That morning, all three lives are forever changed.

Bounced between foster homes, Shannon endures abuse and neglect until she finally finds stability with Miranda, a kind but no-nonsense single mother with a free-spirited daughter of her own. Yet Shannon defines life on her own terms, refusing to settle down, and never stops longing to uncover her roots—especially the stubborn question of why her mother would abandon her on the day she was born.

Brilliantly and hauntingly interwoven with Shannon’s story is the tale of her mother, Yula, a girl herself who is facing a desperate fate in the hours and days leading up to Shannon’s birth. As past and present converge, Y tells an unforgettable story of identity, inheritance, and, ultimately, forgiveness. Celona’s ravishingly beautiful novel offers a deeply affecting look at the choices we make and what it means to be a family, and it marks the debut of a magnificent new voice in contemporary fiction.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

I.

my life begins at the Y. I am born and left in front of the glass doors, and even though the sign is flipped “Closed,” a man is waiting in the parking lot and he sees it all: my mother, a woman in navy coveralls, emerges from behind Christ Church Cathedral with a bundle wrapped in gray, her body bent in the cold wet wind of the summer morning. Her mouth is open as if she is screaming, but there is no sound here, just the calls of birds. The wind gusts and her coveralls blow back from her body, so that the man can see the outline of her skinny legs and distended belly as she walks toward him, the tops of her brown workman’s boots. Her coveralls are stained with motor oil, her boots far too big. She is a small, fine-boned woman, with shoulders so broad that at first the man thinks he is looking at a boy. She has deep brown hair tied back in a bun and wild, moon-gray eyes.

There is a coarse, masculine look to her face, a meanness. Even in the chill, her brow is beaded with sweat. The man watches her stop at the entrance to the parking lot and wrench back her head to look at the sky. She is thinking. Her eyes are wide with determination and fear. She takes a step forward and looks around her. The street is full of pink and gold light from the sun, and the scream of a seaplane comes fast overhead, and the wet of last night’s rain is still present on the street, on the sidewalk, on the buildings’ reflective glass. My mother listens to the plane, to the birds. If anyone sees her, she will lose her nerve. She looks up again, and the morning sky is as blue as a peacock feather.

The man searches her face. He has driven here from Langford this morning, left when it was still so dark that he couldn’t see the trees. Where he lives, deep in the forest, no sky is visible until he reaches the island highway. On his road, the fir trees stretch for hundreds of feet above him and touch at the tips, like a barrel vault. This road is like a nave, he thinks every time he drives it, proud, too proud, of his metaphor, and he looks at the arches, the clerestory, the transept, the choir, the trees. He rolls down his window, feels the rush of wind against his face, in his hair, and pulls onto the highway: finally, the sky, the speed. It opens up ahead of him, and the trees grow shorter and shorter as he gets closer to town; the wide expanse of the highway narrows into Douglas Street, and he passes the bus shelters, through the arc of streetlights, past the car dealership where he used to work, the 7-Eleven, Thompson’s Foam Shop, White Spot, Red Hot Video, and then he is downtown, no trees now, but he can finally smell the ocean, and if he had more time he’d drive right to the tip of the island and watch the sun come up over Dallas Road. It is so early but already the women have their thumbs out, in tight, tight jeans, waiting for the men to arrive in their muddy pickups and dented sedans, and he drives past the Dairy Queen, Traveller’s Inn, the bright red brick of City Hall, the Eaton Centre. By noon, this street he knows so well will be filled with pale-faced rich kids with dreadlocks down to their knees, drumming and shrieking for change, and a man will blow into a trumpet, an orange toque on his head. Later still, the McDonald’s on the corner will fill with teenage beggars, ripped pant legs held together with safety pins, bandanas, patches, their huge backpacks up against the building outside, skinny, brindle-coated pit bulls and pet rats darting in and out of shirtsleeves, sleeping bags, Styrofoam cups, the elderly, so many elderly navigating the mess of these streets, the blind, seagulls, Crystal Gardens, the Helm’s Inn, the totem poles as the man drives past the park toward the YMCA, no other cars but his, because it is, for most people, not morning yet but still the middle of the night.

Now, in the parking lot, he is hidden behind the glare from the rising sun in the passenger-side window of his van. He sees my mother kiss my cheek—a furtive peck like a frightened bird—then walk quickly down the ramp to the entrance, put me in front of the glass doors, and dart away. She doesn’t look back, not even once, and the man watches her turn the corner onto Quadra Street, her strides fast and light now that her arms are empty. She disappears into the cemetery beside the cathedral. It is August 28, at 5:15 a.m. My mother is dead to me, all at once.

The man wishes so badly I weren’t there that he could scream it. All his life, he’s the one who notices the handkerchief drop from an old woman’s purse and has to chase her halfway down the block, waving it like a flag. Every twitch of his eye shows him something he doesn’t want to see: a forgotten lunch bag; the daily soup spelled “dialy”; a patent leather shoe about to step in shit. Wait! Watch out, buster! All this sloppiness, unfinished business. Me. I’m so small he thinks “minute” when he squats and cocks his head. My young mother has wrapped me in a gray sweatshirt with thumbholes because it’s cold this time of day and I’m naked, just a few hours old and jaundiced: a small, yellow thing.

The man unfolds the sweatshirt a bit, searching for a note or signs of damage. There is nothing but a Swiss Army Knife folded up beneath my feet. My head is the size of a Yukon Gold potato. The man pauses. He’s trying to form the sentences he’ll have to say when he pounds the door and calls for help. “Hey! There’s a baby here! A baby left by her mother—I think—I was waiting for the doors to open, she put the baby here and walked away, young girl, not good with ages, late teens, I guess? There’s a baby here, right here. Oh, I didn’t look—” He looks. “It’s a girl.”

There’s a small search. The police mill around and take a description from the man, who tells them his name is Vaughn and that he likes to be the first in the door at the Y in the morning, that it’s like a little game with him.

“Gotta be first at something, guy,” he says to the cop. They look at each other and laugh, a little too hard, for a little too long.

Vaughn is wearing his usual garb: navy track pants with a white racing stripe, a T-shirt with a sailboat on the front, new white running shoes. He is still young, in his early thirties, six feet tall with the build of someone who runs marathons. His red hair is thick and wild on top of his head, and he’s growing a goatee. It itches his chin. He fiddles with it as he talks to the officer. What did you see?

By now Vaughn is used to the way his life works: he is the seer. When the cars collide, he knows it two minutes before it happens. He predicted his parents’ divorce by the way his mother’s lip curled up once, at a party, when his father told a dirty joke. He was nine. He thought, That’s it. That’s the sign. It isn’t hard, this predicting, if that’s what it’s called; it’s a matter of observation. From the right vantage point—say, overhead—it isn’t a matter of psychic ability to see that two people, walking toward each other, heads down, hands in pockets, will eventually collide.

Sir, what did you see?

Vaughn pauses before answering. He feels time slow, and he feels himself float up. From up here, he sees what he needs to: the sequence of events that will befall me if I am raised by my mother. It’s all too clear. He wasn’t meant to see her. He wasn’t meant to intervene. He has seen the look in my mother’s eyes; he has seen women like her before. Whatever my fate, he knows I am better off without her.

What exactly did you see?

And so the officer takes down a description of my mother, but he doesn’t get it right: Vaughn tells him that her hair was short and blond, when the truth is that it was swirled into a dark brown bun. (When she takes it out, it falls to her collarbone.) He says she wore red sweatpants and a white tennis sweater—he finds himself describing his own outfit from the day before—and that she didn’t look homeless, just scared and young. Maybe a university student, he says. An athletic build, he says.

By now, twenty people have gathered in the parking lot of the Y. Some lady pushes through the crowd of officers and people in track pants. She swirls her arms and her mouth opens like a cave.

“My baby!” she shrieks and sets a bag of empty beer cans in a lump at her feet. Her head jerks. The cops roll their eyes and so does Vaughn. She’s the quarter lady—the one who descends when you plug the meter: “Hey, man, got a quarta’?” Her hair is like those wigs at Safeway when you forget to buy a costume for Halloween. If she had wings, she’d look ethereal.

My first baby picture appears in the newspaper. “Abandoned Infant: Police Promise No Charges.” Vaughn cuts out the article and sticks it on his fridge. He’s embarrassed by one of his quotes—“I believe it’s an act of desperation”—and his eyes fill with tears when he reads the passage from Saint Vincent de Paul, which is recited to the press by one of the nurses at the children’s hospital: These children belong to God in a very special way, because they have been abandoned by their mothers and fathers. . . . You cannot have too much affection for them.

“I believe it’s an act of desperation.” Vaughn sucks in a dry breath. The quote makes him cringe and he wishes he had said nothing at all.

He sits at the foot of his bed, waiting for the phone to ring. Surely the police have found my mother; it’s an island, after all. There’s nowhere to go. Once they find her, it will only be a matter of time before they get curious and wonder why his description doesn’t match. He sits on the bed all day and stares at the phone. He stares at it all night. In the morning, he hoists navy blue sheets over the curtain rods to block out the light and wedges newspaper under the door. He sleeps for an hour, dreams that he is hurtling through four floors of a building on fire.

When he wakes, the room is dark but his eyes are burning. He closes his eyes and he is falling through the building again, and when he lands there is blood under his fingernails.

On his bedside table are a picture of his girlfriend, a rolled-up magazine for killing spiders, and a triangular prism. If he opened the curtains, his face would glow a million colors.

Someone, his neighbor, is playing the piano. Poorly, absent-mindedly.

He shakes his head.

“I remembered wrong,” he tells the room, rehearsing, but the phone does not ring.

He reaches for the magazine and knocks the prism to the floor. It doesn’t break. He puts the magazine on his lap and spreads its pages in his hands.

“I space out sometimes. Especially in the morning. I must have gotten her mixed up with someone I saw earlier, or the day before.”

He watches the phone.

He tries to sleep on his back with a pillow pulled over his eyes. He tries to sleep on his stomach. He buries his head in the bedding like a vole.

“I’m sorry,” he says to his empty bedroom, to the image of my mother burned into his mind. “I’m sorry if I did something wrong.”

Finally, he tucks the article into one of the scrapbooks he keeps on top of the refrigerator and tries to forget about me, about my mother and his lie. He knows, somehow, that there was an act of love behind the abandonment. He knows, somehow, he wasn’t meant to intervene.

A wild card, a ticking time bomb. I could be anyone; I could come from anywhere. I have no hair on my head and there’s a vacant look in my eyes, as if I am either unfeeling or stupid.

I weigh a little over four pounds and am placed in a radiant warmer in neonatal intensive care. I test positive for marijuana, negative for amphetamines and methamphetamines. The hospital takes chest X-rays, draws blood from my heel, tests my urine. I do not have pneumonia; I am not infected with HIV. I am put on antibiotics for funisitis, an inflammation of the umbilical cord, and this diagnosis is printed in the newspaper in a final plea for my mother to come forward. She is probably sick, one of the doctors is quoted as saying, and most likely needs treatment. The antibiotics run their course, my mother never appears, and the Ministry of Children and Family Development files for custody.

One of the nurses on the night shift calls me Lily. Her name is Helene, and she is twenty-five years old. She has chestnut-colored, shoulder-length hair that frizzes when it rains, thick bangs, and a small plump face with a rosebud mouth. She stops by on her breaks and sings me “By a Waterfall.”

There’s a whippoorwill that’s calling you-oo-oo-oo

By a waterfall, he’s dreaming, too.

Helene lives alone in an apartment on Esquimalt Road with a view of the ocean. She looks at my tiny face and imagines what her life would be like if she took me home and became my mother. She rearranges her apartment in her mind, puts a bassinet in the small space between her double bed and dresser, replaces one of the foldout chairs at her kitchen table with a high chair. She bakes a Dutch apple pie for me while I watch; all the time she is singing. But Helene meets a man a few weeks later, and her thoughts overflow. She cannot make space for both of us in her mind. She marries the man. They move to Seattle.

I am passed back and forth, cradled in one set of arms and then another. Once it is safe for me to leave the hospital, I am placed in a foster home.

My new parents don’t baptize me because they aren’t religious. They name me Shandi and we live in a noisy brown apartment building in a part of the city that has no name. We are on one of two side streets that connect two major streets, which head in and out of downtown. At night we listen to the traffic on one side coming into town, and the traffic on the other side heading out. There is a corner store a block away, a vacuum repair shop, and a park with a tennis court. City workers come in the morning to clean the public restroom and empty the trashcans, and in the late afternoon, young mothers push strollers down the path, shortcutting to the corner store. At night, the park comes alive. The homeless sleep on the benches or set up tents under the fir trees. The tennis court becomes an open-air market for drugs. In the morning, it is littered with hypodermic needles, buckets of half-eaten KFC, someone’s forgotten sleeping bag. Teenagers from the high school down the street play tennis on the weekends, pausing to roll and smoke joints. It is an otherwise beautiful park, with giant rhododendrons, yew hedges in the shape of giant gumdrops, and Pacific dogwoods with dense, bright-white flowers. A few long-limbed weeping cedars stand here and there amid a barren grassy field.

My foster father’s name is Parez, but he goes by Par. He is satisfied with my meager medical records but my mother, Raquelle, searches my face and body for abnormalities. The night they bring me home, the neighbors, who have three foster children of their own (There’s good money in foster care, they’d said), are waiting in their kitchen with a tuna casserole. “This one’s got no real father and no real mother,” my father, Par, says to them by way of introduction, and sets me on the kitchen table like a whole chicken. “She comes from the moon, from the sky.” He spins around, his arms in the air. He is happy and proud.

In the months that follow, Raquelle feeds me shaky spoonfuls of bouillon,...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 1451674384

- ISBN 13 9781451674385

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Y: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1451674384

Y: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1451674384

Y: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1451674384

Y: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB1451674384

Y: A NOVEL

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.85. Seller Inventory # Q-1451674384