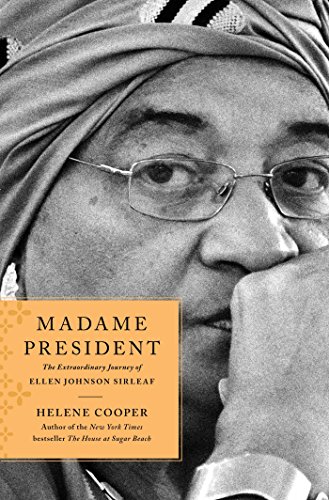

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf - Hardcover

The harrowing, but triumphant story of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, leader of the Liberian women’s movement, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, and the first democratically elected female president in African history.

When Ellen Johnson Sirleaf won the 2005 Liberian presidential election, she demolished a barrier few thought possible, obliterating centuries of patriarchal rule to become the first female elected head of state in Africa’s history. Madame President is the inspiring, often heartbreaking story of Sirleaf’s evolution from an ordinary Liberian mother of four boys to international banking executive, from a victim of domestic violence to a political icon, from a post-war president to a Nobel Peace Prize winner.

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and bestselling author Helene Cooper deftly weaves Sirleaf’s personal story into the larger narrative of the coming of age of Liberian women. The highs and lows of Sirleaf’s life are filled with indelible images; from imprisonment in a jail cell for standing up to Liberia’s military government to addressing the United States Congress, from reeling under the onslaught of the Ebola pandemic to signing a deal with Hillary Clinton when she was still Secretary of State that enshrined American support for Liberia’s future.

Sirleaf’s personality shines throughout this riveting biography. Ultimately, Madame President is the story of Liberia’s greatest daughter, and the universal lessons we can all learn from this “Oracle” of African women.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

In Liberia, a woman’s place is in the market, the church, the kitchen, or the bed. But not for one little girl.

One little girl, delivered in the back bedroom of her family’s house on Benson Street in Monrovia on October 29, 1938, was, her relatives believed, destined for great things. After all, the Old Man, one of the many prophets who wandered through Monrovia spreading their wisdom, predicted it when he showed up at Carney and Martha Johnson’s half-concrete house days after the birth of baby Ellen—nicknamed Red Pumpkin because she was “red like one pumpkin”—to have a look at the baby. “This child will be great,” he said, after peering into the crib. “This child is going to lead.”

Actually, that is not what he said—no Liberian talks like that. Decades later, when Ellen Johnson Sirleaf wrote her own autobiography, she titled it This Child Will Be Great, referencing the Old Man’s prophecy.

She was anglicizing it, assuming an international audience wouldn’t understand Liberian English, which can be perfectly transparent one moment and perfectly impenetrable the next. It is not pidgin, the West African English that evolved from England’s colonial efforts at communicating with Africans. But there is pidgin in Liberian English. Nor is it Creole (see above; insert French). But there is Creole in Liberian English as well.

Instead, Liberian English is a wonderful hodgepodge of all of the above, an international language that borrows freely from British phrasings and American slang, with the added seasoning of the American South, courtesy of the freed American slaves who settled the country, the twenty-eight different ethnic groups who met the slaves when they arrived, and the African parables that are part of daily life.

In Liberia, people talk in continuous parable. Most of the time it makes sense.

“Crab baby die, crab don’t cry, da big-eye bumpy here crying?” (Translation: Why is Marcia more upset about Jan’s ugly afro than Jan is?)

“Fanti man won’t say his fish rotten.” (Do you seriously expect a Chelsea fan to admit they are an awful football club?)

“Me and monkey ain’t make no palaver.” (Why would I turn my nose up at eating the nice monkey meat you put in that palm butter? I’ve got nothing against monkeys.)

“Ehn you know book?” (You’re the one with the Ph.D. You figure it out.)

“I going walkabout.” (I’m going out to visit people, probably a secret boyfriend, and it’s none of your business who, so leave me alone.)

“Monkey work, Baboon draws.” (I do the work, you relax and enjoy yourself.

“Ma, de pekin wa’ na easy oh.” (This child will be great.)

Armed with that prophecy, which her family repeated to her throughout her childhood, Ellen set out to create what would become an extraordinary life. Because before she even uttered her first word, certain things had already been put in place that determined she would be no ordinary Liberian woman.

For this, blame America.

In the early nineteenth century, America found itself with a growing class of freed blacks, many of them the children of slaves who had somehow found themselves freed, for reasons ranging from happenstance to, in many cases, interracial rape. White slave owners had impregnated their slaves, who then had mixed-raced children whose skin color was a daily reminder of the hypocrisy that infused antebellum life. Many of these mixed-race children were eventually freed.

The rising number of freed blacks worried the white slave owners, who believed they served as a beacon to enslaved blacks who might rebel and seek their own freedom. And so began the “back to Africa” movement, centered around the thought that the best way to prevent slave rebellions was to send free blacks back to Africa.

In 1820 the first of many shiploads of mixed-race freed slaves and blacks headed to West Africa. Mulatto, Quadroon, Quintoon, Octaroon—these new colonists were, for the most part, lighter-skinned than the native Liberian population; they could read and write; and they were ostentatiously Christian. The colonists were met by locals who suspected—rightly—that their land and way of life (many of them still actively engaged in the slave trade themselves) were under threat. This was not as morally complicated as it sounds. The Europeans did have to purchase their human cargo from someone, and that someone was usually Africans who had caught and enslaved other Africans. So, many locals in Liberia were worried that this practice would be stopped by the newly arrived former slaves.

And thus was born Liberia, a country of almost impossible social, religious, and political complexity.

The American Colonization Society, a group made up of an unholy combination of white antislavery Quakers and evangelicals and slave owners who wanted to rid their South of freed blacks, purchased land from the native Africans. The Society did this at gunpoint and named the new country Liberia. The freed slaves who colonized Liberia were now the ruling class, and the native Africans largely became the laborers, household help, and underclass.

Liberia is three thousand miles from the Congo, but the black American settlers became known derisively as “Congo people” because native Liberians associated the Congo River with the slave trade. The Congo people controlled the government and owned most of the land. They quickly outlawed the slave trade that had provided income to many of the native Liberians, whom the Congo people referred to insultingly as “country people.”

To the American colonists, the “country people” were an unvariegated mass, with their elaborate beaded jewelry, Fanti clothing, and incomprehensible language. But these were complicated people, from twenty-eight different ethnic groups, with individual beliefs, practices, and centuries-old enmities. The Kru were fishermen who hated slavery. The Krahn brokered deals in slave markets. The Gio came from a line of Sudanese warriors who never ran away from a fight. No one is sure why, but the Gio and Krahn seemed to hate each other.

After several bloody battles in the initial years after their arrival, the American colonists eventually imposed themselves on Liberia’s Gio, Krahn, Bassa, and Kru. What developed next was a symbiotic relationship, particularly in matters of faith. From the Congo people, native Liberians took Christianity. But not the more refined European version. Liberians seized on the robust Christianity of gospel hymns, prayers, and beliefs that the Congo people had brought with them from the land of slavery. The suffering of Jesus Christ and the enslavement of the ancient Jews were things American slaves had intuitively understood. The delivery of his people by Moses, the selling into slavery of Joseph by his brothers, the throwing of Daniel into a lion’s den captured the imagination of the slaves in America.

The Christianity they took with them to Africa was altered dramatically by the native Liberians, who added their own religious interpretations and traditions, including exuberant beating of drums, dancing, singing, and speaking in tongues, creating the background music that the country sways to today.

So when baby Ellen was born, it was to two deeply divided societies that were linked by religion. Yet she, like few others, would not need religion to straddle both groups.

On the outside, Ellen looked like a Congo baby, but she did not have a single drop of Congo blood. She was a native Liberian, a point that would become hugely significant in the coming decades, when the Congo people were finally brought low. Her father’s father was a Gola chief named Jahmale. He had eight wives ensconced in the picturesque village of Julejuah, in Bomi County. He and one wife did what so many Liberians do routinely: they sent one of their sons—Ellen’s father, Karnley—to Monrovia to become a ward of a Congo family. There Karnley could go to school and acquire the refinement that, in early twentieth-century Liberia, was becoming acknowledged as necessary to make something of yourself. Karnley’s name was Westernized to Carney Johnson, beginning the slow Congoization of the family.

Ellen’s mother’s mother was a Kru market woman from Greenville, Sinoe County, named Juah Sarwee, who fell for a white man, a German trader named Heinz Kreuger, who was living in Liberia. The two married in 1913 and had a daughter, Martha.

During World War I, Liberia, eager to show the United States its loyalty, declared war on Germany and expelled all Germans, including Heinz. He left his family behind and was never heard from again. But thanks to Heinz Kreuger and Juah Sarwee, Ellen’s mother, Martha, would go through life with what was then the ultimate symbol of beauty and status in a country with so many hang-ups about race: long hair and light skin. She could almost pass for white. The Congo families soon started offering to take her into their homes—common practice in Liberia, where better-off families often took in poorer children who served as playmates (and sometimes servants) for the children of the house in exchange for room, board, and schooling. Eventually Juah Sarwee, who was poor, illiterate, and abandoned by the white man she had married, agreed to give her daughter away.

The first Congo family Martha lived with made her sleep on the kitchen table, or sometimes under it with the family animals. Early twentieth-century Liberian society might accept that fate for a native, dark-skinned child, but Monrovia wouldn’t tolerate such treatment of a light-skinned half-white girl. So another Congo couple, Cecilia and Charles Dunbar, stepped in to right the wrong.

Martha took the Dunbar name, went to the best schools in Liberia, then headed abroad for a year to acquire even more refinement. She came back and was in the yard of the Dunbar house when Ellen’s father, now Carney Johnson, spotted her.

“Oh,” he said, taking in the hair, figure, and flushed high-yellow skin. “Oh. I like you.”

* * *

Martha and Carney’s four children—first Charles, then Jennie, Ellen, and Carney—would grow up with the gift of camouflage in a fractured country. Among the Congo people they could easily fit in, yet their Gola roots also gave them an entrée, should they ever want to use it, into native Liberian culture. Ellen, the third child, in particular had the ability to use the gift with which she was born.

She looked Congo, and like most Congo people, she spoke two languages: English and Liberian English. She certainly lived Congo: she went to school with the Congo kids and lived in a real cement house on Benson Street with a big yard surrounded by coconut trees and filled with fruit and flower bushes. Her older sister even went to school in England, a prized status that was the height of Congoness. By local standards, the family was upper middle class, thanks to Martha’s light skin, but especially to Carney’s profession as a lawyer. He was eventually elected to the Liberian House of Representatives, the first native Liberian to do so.

Ellen was four years old when William V. S. Tubman was elected president in 1943. Luckily for their family, the president appeared to like her father. Tubman would often dispatch Johnson abroad to represent the country, and when Johnson returned from such trips, the president sometimes visited the family home with his entourage, an event that certainly enhanced their standing in society but led to mayhem in the kitchen as servants and helpers cooked palm butter, jollof rice—the proper Liberian jollof rice, with chicken and ham hock and beef in it—and fufu for the head of state. Naturally Ellen and her siblings were banished from the living room, but Ellen always hid around the corner to listen.

Ellen was firmly in the ruling Congo class, except when she didn’t want to be. She attended the College of West Africa, an elite high school. During vacations, she and her sister and brothers went to Julejuah, the village in Bomi County where their father was born. Julejuah was twenty miles from Monrovia, but the road ended well before the village, so their car could take them only to that point. Men carried Ellen and her siblings in hammocks the rest of the way.

Once in Julejuah, Ellen and the boys—Jennie turned her nose up at such tomboyish behavior—climbed trees, swam in the river, hitched rides in the canoe that ferried people from one bank to the other, and sat under a tree out of the hot sun with their grandmother eyeing the birds that approached the growing rice. Recognizing that Jennie was their father’s favorite, Ellen and her brothers sent her to canoodle sweets and favors from him. They learned a smattering of Gola words, the language of their ancestors. Those few phrases would one day save Ellen’s life.

* * *

Throughout Ellen’s growing-up years, her family reminded her, often with irony, that she was a pekin who wa’ na easy oh, destined for greatness. Often they brought it up when she did something that didn’t seem so great. Like, for instance, the day she fell into the latrine.

The family house on Benson Street was luxurious by the standards of 1950s Liberia: a two-story concrete structure with a big yard. But it didn’t have an indoor bathroom; an outdoor latrine of rough plank boards over a deep hole was the family toilet. Once, when she was small, Ellen fell in. She hollered and carried on until a passing neighbor pulled her out and helped her mother wash her off.

The family invoked the prophecy when Ellen made her first public speech, at the age of eight. Or, at least, she tried to, spending the whole afternoon the day before her much anticipated Sunday recitation sitting under a guava tree memorizing her lines. Alas, when she was called before the congregation at church the next morning, she froze, looking at her mother’s agonized face, standing there for minute after unbearable minute. Finally, the congregation started clapping in sympathy, and Ellen, tears running down her face, returned to her seat in disgrace.

They should definitely have invoked the prophecy when, at the age of seventeen, Ellen became a bride.

It was 1956, and the once-prosperous family had had a change of fortune. Carney Johnson had suffered a stroke that paralyzed his right side. “I have been witched,” he informed his family. “Someone has put juju on me.” In Liberia it is still common for people to reach for ominous explanations for otherwise scientifically explicable phenomena. His wife also eschewed the scientific for the less tangible. “Pray for healing and for the forgiveness of your sins,” Martha advised her husband.

Carney’s speech and movement were compromised by the stroke, and with that, his hopes of becoming the first native Liberian speaker of the House died. His past closeness to the ruling class wasn’t enough to insulate his family from the results of his vanished income. Martha quickly turned to the Liberian woman’s standard for survival, marketing, and began making baked goods to sell. She also took over the all-encompassing care and feeding of her now-homebound husband, rising early to bathe, dress, and feed him before helping him to the chair on the porch where he spent his days staring out at the street.

At sixteen Ellen was nearing the end of high school, hoping that she wo...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2017

- ISBN 10 145169735X

- ISBN 13 9781451697353

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # ICM.37EE

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 145169735X-2-1

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-145169735X-new

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # DADAX145169735X

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_145169735X

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think145169735X

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover145169735X

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard145169735X

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf **SIGNED 1st Edition /1st Printing**

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. Signed in person by Helene Cooper directly on the title page. NOT signed to anyone. A copy of the signing event announcement will be included with the signed book. 1st Edition/ 1st printing with a full number line:1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2. Hardcover. Book is BRAND NEW and UNREAD, opened only for signing. No marks, no inscription. Not a book club edition, not an ex-library. Dust jacket is new, not price clipped, in a removable, protective clear cover. This is a beautiful autographed book. Makes a great gift. Signed by Author(s). Seller Inventory # 001306

Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 384 pages. 9.50x6.50x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # zk145169735X