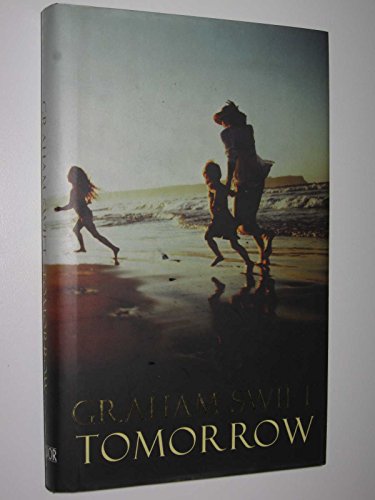

Synopsis

In his first novel since The Light of Day, the Booker Prize–winning author gives us a luminous tale about the closest of human bonds.

On a midsummer’s night Paula Hook lies awake; Mike, her husband of twenty-five years, asleep beside her; her teenage twins, Nick and Kate, sleeping in nearby rooms. The next day, she knows, will redefine all of their lives. A revelation lies in store. Her children’s future lies before them. The house holds the family’s history and fate.

Recalling the years before and after her children were born, Paula begins a story that is both a glowing celebration of love possessed and a moving acknowledgment of the fear of loss, of the fragilities, illusions, and secrets on which even our most intimate sense of who we are can rest. As day draws nearer, Paula’s intensely personal thoughts touch on all our tomorrows.

Brilliantly distilling half a century into one suspenseful night, as tender in its tone as it is deep in its soundings, Tomorrow is an eloquent exploration of couples, parenthood, and selfhood, and a unique meditation on the mystery of happiness.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Graham Swift lives in London and is the author of seven previous novels: The Sweet-Shop Owner; Shuttlecock, which received the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize; Waterland, which was short-listed for the Booker Prize and won the Guardian Fiction Award, the Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize, and the Italian Premio Grinzane Cavour; Out of This World; Ever After, which won the French Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger; Last Orders, which was awarded the Booker Prize; and, most recently, The Light of Day. He is also the author of Learning to Swim, a collection of short stories. His work has been translated into more than thirty languages.

Reviews

Reviewed by Ron Charles

For the second time this year, a Booker Prize winner has given us a short novel about a single night in bed. In June, Ian McEwan described an awkward honeymoon on Chesil Beach. And now Graham Swift wants to keep us awake with Tomorrow, a monologue in which a mother lies next to her husband, worrying about a revelation that will soon alter their lives. Superficially, both novels are about sex in the 1960s: for McEwan, really bad sex, and for Swift, really good sex. But while McEwan makes us cringe at his careful analysis of two nervous virgins, Swift makes us cringe for entirely different reasons.

Tomorrow opens in the anxious hours of a midsummer's night in 1995. Paula Hook, an art dealer in London, is obsessing over the horrible news that she and her husband will reveal to their 16-year-old twins in the morning: "You're asleep, my angels," she says. "So, to my amazement and relief, is your father, like a man finding it in him to sleep on the eve of his execution."

What an exquisitely suspenseful introduction, and Graham ratchets up our apprehension with each paragraph. Since Nick and Kate were born, Paula and her husband have been dreading this day. Dishes from the "terminal supper" of their "last day" have been put away, and now she imagines the coming scene at breakfast, how her husband will deliver "the biggest speech of his life," how her children will receive the news. "It's time you were told," she thinks, but will her husband survive the ordeal? "I picture a bomb going off and this house falling to bits." And then, just when you can't stand the anxiety of this mystery one more moment, it goes on for 100 more pages:

"How different tomorrow will be."

"Tomorrow looks like being a rainy day, my darlings."

"It's a lasting sadness to me, and it will have its extra stab tomorrow."

"We'll see tomorrow."

"Your dad will explain tomorrow."

"He'll give you these intimate details tomorrow."

"Perhaps tomorrow you'll try to dig up some more."

"You have to face tomorrow."

"What will happen tomorrow?"

This is coyness raised to the level of waterboarding. By the time Paula observes, "You must both be starting to muster an intense interest," I knew why her husband was lying next to her dead asleep. And what horrendous mystery could possibly justify these 150 pages of anxious delay? Have Paula and her husband attained their comfortable middle-class lifestyle through drug-running or child prostitution? Did they acquire their beloved twins from a murdered dissident during Argentina's Dirty War? Are they closet Nazi transsexuals from planet Zorkon? No, none of that would even begin to satisfy the level of suspense Paula raises in this claustrophobic narrative. And so it comes as a particularly bitter disappointment when she finally reveals the rather ordinary news that will shatter their lives. I won't spoil it for you here, but it's something like watching "The Crying Game" only to discover that Forest Whitaker is a black man.

Swift's overemphasis on this domestic mystery is a fatal distraction in what might have been a compelling meditation on family relations, but there's another equally weird misstep here. Tomorrow isn't just a woman's late-night ruminations on her life; again and again, Swift reminds us that she's rehearsing a confession to her 16-year-old twins. She wants to explain herself and her life to them. It's a story that takes her back to her college days, her courtship of their father and the striking social revolutions of the 1960s.

"What made that age so new, so different from previous ages," she explains, "was a little pill: once a day for twenty-one days, then a week off." Well, okay: Nothing wrong with a little frank talk between a hip middle-age mom and her savvy teenage kids. But that candor quickly descends into the-birds-and-the-bees talk from hell.

"At sixteen you're both virgins," she announces, but they're old enough to hear this: "I met your father when I was twenty and he was twenty-one, in Brighton, in 1966, when we were both at Sussex University. When I say 'met' I really mean 'went to bed with,' 'slept with,' if there wasn't, that night, that much sleeping." If you're starting to feel a little uncomfortable, prepare to squirm.

Anyone listening at the door that night, she says, would have "heard our thrustings and thrashings-about certainly, and later on heard something softer, slower, just a lovely, steady undulation . . . the merest gentle creaking of my bed. . . . We were engaged in a wonderful, slow, wave-like motion that neither of us wanted to stop. . . . I didn't want to interrupt your daddy's sweet and gathering rhythm."

Maybe I'm a prude, but "your Daddy's sweet and gathering rhythm" is a phrase that I could live without. And there are so many others here: "We started to make love again," she imagines telling her children, "with a new -- I don't think it's the wrong word -- potency." In fact, they made love "in some fine places," in "some little niche, some cupboard somewhere, a space in one of the store rooms, among the artworks, where we could have immediate and urgent sexual congress." There's a long passage about how their cat used to watch them having sex. There are frequent discussions of their father's semen. Elsewhere, she describes their sexual positions ("against all mechanistic wisdom"), how their father likes to cry out, how loud she is and even how she had to clean herself afterward.

"I've said too much already," Paula says (too late!), but then she goes on:

"Let me tell you that the early mornings have always been our favourite time for it." Good to know, Mom.

It's enough to make one question the propriety of a male author trying to write in a woman's voice. All of these needlessly intimate details are spilled out in a misguided sense that her teenage children will "want to know everything, the full, complete and intricate story."

My own 16-year-old daughter, sitting in the back seat as I read to my wife in quieter and quieter tones, finally piped up and said, "Please don't let this give you any ideas." And when I got to Paula asking, "Should I be telling you this?" everyone in the car blurted out, "No!"

Copyright 2007, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.

Bad books sometimes happen to good authors. Despite compelling themes-the unpredictability of life, the ways we mask emotional trauma to produce happiness-Tomorrow failed to muster praise from even the most generous of critics. After building up a doom-and-gloom scenario, Graham Swift led reviewers to expect a tragedy of monstrous proportions-perhaps the children are aliens or the parents serial killers. None of these scenarios panned out, leaving critics feeling deflated upon learning the truth. A monotonous, repetitive (if often insightful) narrator and gratuitous sex scenes that a mother would never share with her children likewise blindsided critics. Ah well.

Copyright © 2004 Phillips & Nelson Media, Inc.

This splendid novel by Booker Prize–winner Smith (for Last Orders) has its roots in the 1960s sexual awakening and takes place over the course of a sleepless night in June 1995. Paula Campbell Hook lies awake beside her sleeping husband, Mike, and worries about the shocking revelation that she and Mike will make to their 16-year-old twins tomorrow. Paula recalls her meeting with Mike at university in 1966, when sex was free and easy (a glut of it), the immediate consummation of their sexual passion, their marriage and successful careers, and the birth of the twins after almost a decade together. Mainly, Swift explores the ways in which secrets are created to ensure happiness, and the potential for emotional damage when the truth is revealed. Swift has channeled the tenderness in Paula's voice with uncanny exactitude, granting her a mother's sentimental observations about pregnancy and raising children. He drops a few clever red herrings, so the narrative retains the vibrato of suspense until the secret is revealed. But the novel's remaining pages, which convey the exaggerated doomsday fears of middle-of-the night wakefulness, seem padded. In essence, this moving exploration of marriage and parenthood is a ringing affirmation of modern life. (Sept.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Throughout his career, Swift has made good use of stories that unfold backward, working toward revelations about the past. But the strategy misfires badly in this novel, narrated by a woman lying awake next to her sleeping husband and mentally talking to her sixteen-year-old twins about a secret whose revelation, the next day, will change their lives. The problem is partly that the secret turns out to be unmomentous, but also that it is used as a device to lead us through the history of a marriage—student love in the sixties, career choices, deaths of a cat and a parent—that has little narrative impetus of its own. Presumably, Swift is trying to celebrate ordinariness, but he seems to have been unsure how to do it.

Copyright © 2007 Click here to subscribe to The New Yorker

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter One

You're asleep, my angels, I assume. So, to my amazement and relief, is your father, like a man finding it in him to sleep on the eve of his execution. He'll need all he can muster tomorrow. I'm the only one awake in this house on this night before the day that will change all our lives. Though it's already that day: the little luminous hands on my alarm clock (which I haven't set) show just gone one in the morning. And the nights are short. It's almost midsummer, 1995. It's a week past your sixteenth birthday. By a fluke that's become something of an embarrassment and that some people will say wasn't a fluke at all, you were born in Gemini. I'm not an especially superstitious woman. I married a scientist. But one little thing I'll do tomorrow—today, I mean, but for a little while still I can keep up the illusion—is cross my fingers.

Everything's quiet, the house is still. Mike and I have anticipated this moment, we've talked about it and rehearsed it in our heads so many times that recently it's sometimes seemed like a relief: it's actually come. On the other hand, it's monstrous, it's outrageous—and it's in our power to postpone it. But "after their sixteenth birthday," we said, and let's be strict about it. Perhaps you may even appreciate our discipline and tact. Let's be strict, but let's not be cruel. Give them a week. Let them have their birthday, their last birthday of that old life.

You're sleeping the deep sleep of teenagers. I just about remember it. I wonder how you'll sleep tomorrow.

Sixteen was old enough, sixteen was about right. You're not kids any more, you'd be the first to endorse that. And even in the last sixteen years, you could say, sixteen's become older. Sixteen now is like eighteen was, sixteen years ago. There's an acceleration, an upgrading to things that scare me, but seem hardly to touch you. 1995—already. I'll be fifty in August, I'll have done my annual catching up with your father. What a year of big numbers. Fifty, of course, is nothing now, it's last season's forty. Life's getting longer, more elastic. But that doesn't stop the years getting quicker, this feeling that the world is hurtling.

Perhaps you don't feel it, in your becalmed teenage sleep. Perhaps you want the world to hurtle. Come on, can't it go any faster? Perhaps what all parents want from their children is to feel again that deep, long, almost stationary slowness of time. Another sweet taste of it, please.

But sixteen years have passed and sixteen's like eighteen once was, maybe. But that doesn't matter. To me, tonight, you're still little kids, you're tiny babies, as if you might be sleeping now, not in your separate dens of rooms, but together as you once did in a single cot at Davenport Road. Our Nick and Kate. And what I'm feeling now is simply the most awful thing: that we might be wrenching you for ever from your childhood, in the same way as if you might have been wrenched once prematurely and dangerously from my womb. But you were right on time: the tenth of June 1979. And at two, as it happens, in the morning.

Mike will do the talking. He knows, he accepts that it's up to him. On a Saturday, knowing you both, the morning will be half gone before you even appear for breakfast, and you'll need your breakfast. Then Mike will say that we need to talk to you. He'll say it in an odd, uncasual way, and you'll think twice about answering back. No, right now, please. Whatever other plans you had, drop them. There'll be something in his voice. He'll ask you to sit in the living room. I'll make some fresh coffee. You'll wonder what the hell is going on. You'll think your father's looking rather strange. But then you might have noticed that already, you might have noticed it all this week. What's up with Dad? What's up with the pair of them?

As he asks you to sit, side by side, on the sofa (we've even discussed such minor details), you'll do a quick run-through in your minds of all those stories that friends at school have shared with you: inside stories, little bulletins on domestic crisis. It's your turn now, perhaps. It has the feeling of catastrophe. He's about to tell you (despite, I hope, your strongest suppositions) that he and I are splitting up. Something's been going on now for a little while. He's been having an affair with one of those (young and picked by him) women at his office. An Emma or a Charlotte. God forbid. Or I've been having an affair (God forbid indeed) with Simon at Walker's, or with one of our esteemed but importunate clients. Married life here in Rutherford Road is not all it seems. Success and money, they do funny things. So does being fifty.

You're in tune with such under-the-surface stuff from your between-lessons gossip. It's part of your education: the hidden life of Putney.

But then—you're sixteen. Do you notice, these days, that much about us at all? Do you pick up on our moods and secrecies? We've had a few rows in recent weeks, have you actually noticed? And we don't often row. But then, so have you. You're at a stage—don't think I haven't noticed—when that cord, that invisible rope that runs between you has been stretched to its limit. It's been yanked and tugged this way and that. You have your own worlds to deal with.

And you've only just finished your exams. Ordeal enough. This should have been a weekend of recuperation. And if you'd still had more exams to go we'd have stretched our timetable to accommodate them. Let's not ruin their chances, let's not spoil their concentration. Bad enough that your birthday, last weekend, should have been subject to your last bouts of revision. As it is, we've been tempted. Let's wait—till after the results perhaps, till after one more precious summer. But we came back to our firm ruling: one week's cushion only. And since your birthday fell this year, handily, on a Saturday . . . Forgive us, there's more revision. Exams can affect your life. So can this.

Mike will do the talking. I'll add my bits. And, of course, when he's finished he'll make himself open to questions, as many as you wish. To cross-examination, might be the better expression. It all just might, conceivably, go to plan, though I'm not sure what the "plan" really is, apart from our rigorous timing. It might all be like some meeting that smoothly and efficiently accomplishes its purpose, but it can hardly be like one of your dad's board meetings or one of our cursory get-togethers at Walker's: "That was all dealt with at the meeting . . ."

I think, anyway, you'll want to know everything, the full, complete and intricate story. And you deserve it, as a matter of record.

Your father is gently snoring.

I remember once you said to me, Kate: "Tell me about before I was born." Such simply uttered and innocent words: they sent a shiver through me. I should have been delighted, charmed, even a little flattered. You actually had a concept of a time before you were around, a dawning interest in it. You saw it had some magic connection with you, if you still thought of it, maybe, like life on another planet.

How old were you then—eight? We were on the beach in Cornwall, at Carrack Cove, we had those three summers there, this must have been the second. I'd wrapped you in the big faded-blue beach towel and was rubbing you gently dry, and I remember thinking that the towel was no longer like something inside which you could get lost and smothered, you were so much bigger now. And a whole year had passed since the time when, off that same beach, you both quite suddenly learnt to swim. First you, then Nick almost immediately afterwards, like clockwork. One of those first-time and once-only moments of life. But I'd suddenly called you "a pair of shrimps." Why not "fish?" Or "heroes?" I suppose it was the pinkness and littleness. I suppose it was the way you just jerked and scudded around furiously but ecstatically in the shallows, hardly fish-like at all. I didn't want to think of you yet swimming out to sea. Shrimps.

Did you notice the odd look in my eye? A perfectly innocent question, but there was something strange about it. You said, "Before I was born," not "we." Nick was still down at the water's edge with Mike. He came up so much higher against Mike now, and Mike's always been a good, lean height. Did you notice my little teeter? But I would have quickly smiled, I hope. I would have quickly got all wistful and girl-to-girl, if still motherly. I kept on rubbing you and I told you, you'll remember, about another beach, far away in Scotland, where, I said, your daddy "proposed" to me. In a sand dune, in fact.

That was eight years ago. Half your life. I could still dare to wear a bikini. It was one of those many panicky but smoothed-over moments—you'll understand soon what I mean—which have sometimes brought Mike and me to a sort of brink. Why not now? Oh, we've had our jitters. But we've kept to our schedule. It will be up to you, tomorrow, to judge, to tell us if, in the circumstances, you'd have done the same. But what a stupid idea: if you'd have done the same!

You said you'd like to propose to Nick—to practise proposing to Nick. I said it didn't tend to work that way round, and it was a thing, anyway, that belonged to "those old days." And suppose, I said, Nick should say no? My bikini was dark brown, your little costume was tangerine. It's men, I said, if it happens at all now, who do the proposing.

And sometimes the explaining. But I think you both deserve the full story from me, your mother. Mike will give you his story, his version. I mean, it won't be a story, it will be the facts, a story is what you've had so far. All the same, it will be a sort of version of something real. One thing we've learnt in these sixteen years is how hard it can be to tell what's true and what's false, what's real and what's pretend. It's one thi...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for Tomorrow

Tomorrow

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00042998695

Tomorrow

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. Seller Inventory # WAL-H-3f-002584

Tomorrow

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. . GoodFormer Library book. All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. Seller Inventory # WAL-L-1h-002132

Tomorrow

Seller: Books-FYI, Inc., Cadiz, KY, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 23MA36018W5R_ns

Tomorrow

Seller: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . Seller Inventory # mon0000748805

Tomorrow

Seller: Preferred Books, Rancho Cucamonga, CA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fine. 1st Edition. Looks new and unread. In his first novel sinceThe Light of Day, the Booker Prizewinning author gives us a luminous tale about the closest of human bonds. On a midsummer's night Paula Hook lies awake; Mike, her husband of twenty-five years, asleep beside her; her teenage twins, Nick and Kate, sleeping in nearby rooms. The next day, she knows, will redefine all of their lives. A revelation lies in store. Her children's future lies before them. The house holds the family's history and fate. Recalling the years before and after her children were born, Paula begins a story that is both a glowing celebration of love possessed and a moving acknowledgment of the fear of loss, of the fragilities, illusions, and secrets on which even our most intimate sense of who we are can rest. As day draws nearer, Paula's intensely personal thoughts touch on all our tomorrows. Brilliantly distilling half a century into one suspenseful night, as tender in its tone as it is deep in its soundings,Tomorrowis an eloquent exploration of couples, parenthood, and selfhood, and a unique meditation on the mystery of happiness. Seller Inventory # 008886

Tomorrow

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. states. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP102732791

Tomorrow

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. states. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 38269783-6

Tomorrow

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0307266907I4N00

Tomorrow

Seller: HPB-Emerald, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_449796605