Items related to A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq's...

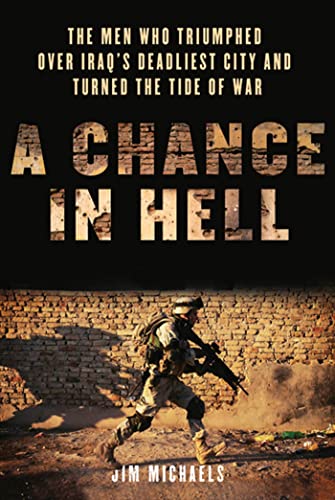

A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq's Deadliest City and Turned the Tide of War - Softcover

The riveting account of how one brigade turned Iraq's most violent city into a model of stability

Colonel Sean MacFarland arrived in Iraq's deadliest city with simple instructions: pacify Ramadi without destroying it. The odds were against him from the start. By 2006, insurgents roamed freely in many parts of the city in open defiance of Iraq's U.S.-backed government. Al-Qaeda had boldly declared Ramadi its capital. Even the U.S. military acknowledged that the province would be the last to be pacified.

MacFarland laid out a bold plan. His soldiers would take on the insurgents in their own backyard. He set up combat outposts in the city's most dangerous neighborhoods. Snipers roamed the back alleys, killing al-Qaeda leaders and terrorist cells. U.S. tanks rumbled down the streets, firing point-blank into buildings occupied by insurgents. MacFarland's brigade engaged in some of the bloodiest street fighting of the war. Casualties on both sides mounted. Al-Qaeda wasn't going to give up easily--Ramadi was too important. MacFarland wasn't going to back down, either.

A Chance in Hell tells how a handful of men turned the tide of war at a time when it appeared all hope was lost.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Hero Flight

Behold, as may unworthiness define,

A little touch of Harry in the night.

—HENRY V

The doors opened, spilling a pool of yellow light into the darkness. Four stretcher bearers came out with the remains of Private First Class Brett Tribble, zipped into a black plastic body bag. The soldiers stood in two ranks, lining the gravel road in front of the makeshift morgue—a plywood building equipped with extra air conditioners to keep the bodies cool. First Sgt. David Shaw called the men to attention and the soldiers saluted as the stretcher bearers moved slowly down the ranks. It was silent, except for the scrape of the litter-bearers’ boots against the gravel road.

Capt. Artie Maxwell, the battalion chaplain, recited the Twenty-third Psalm: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . .” The stretcher bearers—four noncommissioned officers from Tribble’s company—placed his body carefully in the back of a waiting field ambulance. The two ranks then closed into one and formed a pro cession behind the ambulance, which turned left and drove slowly toward the helicopter landing zone, about a hundred yards away. Small green chemlites placed on the side of the road marked the path dimly.

The drone of the helicopters grew deafening as the birds approached the landing zone. A pair of Marine Corps CH-46s closed in, their gray drab airframes barely lighter than the dark sky. In 2006, most helicopters in Anbar Province flew at night with their running lights off to avoid ground fire. They didn’t remain on the ground long. The camp was often the target of enemy rocket and mortar fire. The helicopters hovered briefly and then settled on the sand, squatting in the darkness as their blades continued to turn, violently stirring the warm air and sending out a blast of small rocks and debris. Guided by the helicopter’s helmeted crew chief, the stretcher bearers crouched and moved through the rotor wash toward the back of the bird, carefully placing Tribble’s remains on board and then walking off the landing zone. The soldiers came to attention and saluted a last time. The ramp closed, the engines whined, and the helicopters hesitated briefly before climbing, kicking up another blast of debris in their wake and forcing the soldiers to turn their heads away.

The aircraft climbed until they were swallowed by the darkness.

Tribble was raised in a small town south of Houston and his parents made a living off the chemical plants that cluster along the Gulf Coast. His mother worked in an office as an expediter and his father as a pipe fabricator. They divorced when he was thirteen, and Tribble and his two brothers were raised by his mom.

At age fourteen he was in a car with two buddies. One of them poked his upper body through the car’s sunroof and fired a .38 pistol at the home of a girl who had jilted him. For Tribble it was the beginning of a troubled period during which he was in and out of juvenile detention facilities. He had spent so much time in juvenile detention he couldn’t fit back into high school. He tried his hand at pipe fitting work with his dad and enrolled for a time in welder’s school. Neither worked.

At seventeen, he found himself without a job or a high school diploma—and with a pregnant girlfriend who wasn’t sure she wanted to stay with him.

His mother, Tracy Tribble, came home from work and found him lying on his bed, crying.

“Mom, I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

It was odd. He wasn’t one to express his feelings. His mother figured he had got a glimpse of his future and had panicked. Pending fatherhood had focused his mind.

His mother suggested the army. She had read about the military and how it provided direction and discipline to young men without either. “Let them show you the world,” she said. “Let them pay for your education.”

He said nothing.

Several months later, Tribble told his mother he had enlisted in the U.S. Army. The recruiter had worked to have some of the felonies on his record dropped to misdemeanors and he was off to basic training.

He returned a changed person. He had lost the chip on his shoulder and seemed more at ease, less angry. His mother hoped the changes were for good. Tribble signed up for the infantry even though his recruiter told him there were lots of other options in the army. He was good at infantry skills and the army meant steady pay.

His mom, stepmother, and brother Clint drove to Fort Benning, Georgia, to see him graduate from infantry training. Tracy Tribble choked back tears as she watched the band, the cannon fire, and the rest of the pageantry.

Tribble received orders to a battalion in Germany that was getting ready for another Iraq tour. It was his first time on a plane and he landed wide-eyed in Europe. The base was huge, with all the comforts of an American town. He and his friends explored the country. He told his mom about taking a train ride and eating in a restaurant that was hundreds of years old.

“You ought to see this place,” he told her over the phone.

“I need to get promoted so I can be making some money for my boy,” Tribble told his friend, Jason Dickerson, a medic.

He had an easy personality that drew people to him and he was good at what he did. He had found a home.

His battalion was sent to Kuwait, where it served as part of the “strategic reserve.” It wouldn’t go to Iraq unless things were going bad.

The Pentagon had expected a short war to overthrow Saddam’s regime. By 2006 America was faced with a growing insurgency and sectarian violence that threatened to engulf Iraq in a civil war. The military, which had shrunk dramatically after the cold war, was struggling to come up with enough troops to deal with the twin challenges in Iraq.

In 2006, Gen. George Casey, the top U.S. commander in Iraq, decided to commit his reserves to the fight. He had no choice. Things were spiraling out of control. Tribble’s battalion, 1-35 Armor, would go to Ramadi, the provincial capital of Anbar Province and the heart of the Sunni insurgency. Tribble and his friends had followed the news while in Kuwait. They had seen the television images from Ramadi. They knew it was Iraq’s deadliest city.

Tribble’s mom took his call at work. She rushed into the company cafeteria where she could talk privately. Her son told her they were in a really bad area. He couldn’t say more.

Tribble had been in Iraq less than a week when he volunteered to man the gunner’s hatch on a night patrol planned for Ramadi’s Tameem neighborhood, one of the city’s worst areas. He was supposed to be a “dismount,” meaning he would sit in the back of the vehicle and only get out when required for a foot patrol. Tribble asked if he could be a gunner instead. Dismounts were little more than passengers until action happened. Standing in the gunner’s hatch with your body partially exposed was more dangerous. That’s where Tribble wanted to be.

Sgt. Tom Davis, the squad leader, and Dickerson were leaning over a map spread on the hood of a Humvee, going over that evening’s patrol. Tribble came over and draped his arm over Dickerson and peered at the map. Dickerson could tell he was excited.

“I’m gunning to night,” Tribble said with a grin.

Dickerson, twenty-two, was less gung ho. He had had a previous combat tour in Baghdad. As a medic, his job forced him to dwell on war’s ugly side. When the unit was in Kuwait, Lt. Col. John Farr, the battalion doctor, called the medics into a meeting in a large tent when they learned they were heading to Ramadi.

“You guys are going to the most dangerous city in the most dangerous country in the world right now,” Farr told them. “You’re going to see combat.”

Dickerson was in no hurry to get back to Iraq.

The patrol rolled out of Camp Ramadi at about 9 P.M., with three Humvees and two Bradleys, large heavily armored vehicles. The Bradleys went off and established fixed checkpoints in the darkened streets and the Humvees rolled farther into Tameem. A Humvee with National Guard soldiers from the unit they were replacing accompanied the patrol for part of the way, but they also moved off to set up a checkpoint. It was their last night patrolling the city before heading home. They didn’t want to take unnecessary risks and they were in a hurry to get out of Ramadi. Tribble’s battalion had just arrived in Iraq from Kuwait and hadn’t even officially taken over the “battle space” yet.

The military calls this kind of handoff a “relief in place,” and it is considered one of the most dangerous operations a unit can perform. It thickens the fog of war as a new group attempts to step into the role of the departing unit while the enemy continues attacking.

That left the new men to feel their way along unfamiliar streets. Davis and his men frequently checked maps inside their darkened vehicles, trying to identify what roads were passable and what routes they had been warned to avoid.

It had been a long day for the new men, who had been working in the hot sun since 7 A.M. The soldiers had been scrambling since they had arrived from Kuwait. The company had received some Humvees from another unit and had to inspect each one. They had to bolt additional armor onto the Bradleys. Then during last-minute checks, they discovered that there were problems with the radios. Davis had communication with the other Humvees in his patrol, but only sporadically with his platoon leader. Patrols had to be on the streets 24/7. There was no way they could pause for several days to get their bearings.

Davis had had a previous tour in Baghdad and noticed the difference as soon as he landed in Ramadi. In Baghdad, children would wave at patrols. Even adults would occasionally smile at American soldiers.

“I had seen what it was like when pe...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Griffin

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0312569521

- ISBN 13 9780312569525

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq's Deadliest City and Turned the Tide of War

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0312569521

A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq's Deadliest City and Turned the Tide of War

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0312569521

A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq's Deadliest City and Turned the Tide of War

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0312569521

A Chance in Hell: The Men Who Triumphed Over Iraq's Deadliest City and Turned the Tide of War

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0312569521