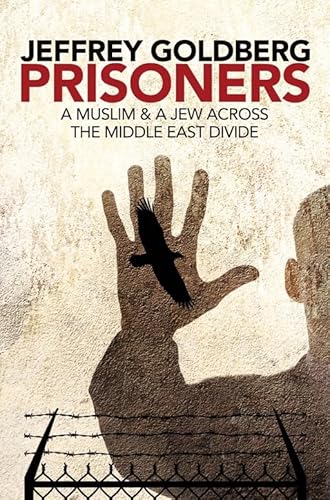

Items related to Prisoners, a Muslim and Jew Across the Middle East...

During the first Palestinian uprising in 1990, Jeffrey Goldberg – an American Jew – served as a guard at the largest prison camp in Israel. One of his prisoners was Rafiq, a rising leader in the PLO. Overcoming their fears and prejudices, the two men began a dialogue that, over more than a decade, grew into a remarkable friendship. Now an award-winning journalist, Goldberg describes their relationship and their confrontations over religious, cultural, and political differences; through these discussions, he attempts to make sense of the conflicts in this embattled region, revealing the truths that lie buried within the animosities of the Middle East.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Jeffrey Goldberg is the Washington correspondent of The New Yorker; he was Middle East correspondent from 2000-2005. Previously he covered the Middle East for The New York Times Magazine. He has also written for The Forward, The Jerusalem Post, and The Washington Post. His awards include a National Magazine Award in Reporting, an Overseas Press Club Award for Human Rights Reporting, and selection as International Investigative Journalist of the Year by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. He served as a Public Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington. He is married and has three children.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chapter One

THE THIEF OF MERCY

On the morning of the fine spring day, full of sunshine, that ended with my arrest in Gaza, I woke early from an uneven sleep, dressed, and pushed back to its proper place the desk meant to barricade the door of my hotel room. I unknotted the bedsheets I had tied together into an emergency escape ladder. Then I hid the knife I kept under my pillow, cleaned the dust from my shoes, and carefully unbolted the door. I searched the dark hall. There were no signs of imminent peril. Most people wouldn’t be so cautious, but I had my reasons, and not all of them were rooted in self-flattering paranoia.

I was staying at the al-Deira hotel, a fine hotel, one of Gaza’s main charms. On hot nights, which are most nights, it brimmed over with members of haute Palestine, that small clique of Gazans who earned more than negligible incomes. The men smoked apple-flavored tobacco from water pipes; the women, their heads covered, drank strong coffee and kept quiet.

By day the hotel was mostly empty. The hotels of Gaza had been full in the 1990s, during the long moment of false grace manufactured by the Oslo peace process. In 1993, Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat shook hands on the White House lawn, and it seemed as if the hate would melt away like wax. At that moment, even a pessimist could envision an orderly close to the one-hundred-year-long war between Arab and Jew. But this was now the spring of 2001, and we were six months inside the Palestinian Uprising, the Intifada, the second Intifada, this one far more grim than the last. The land between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan was once again steeped in blood: Arabs were killing Jews, and Jews were killing Arabs, and hope seemed to be in permanent eclipse. Optimists, and I included myself in this category, felt as if we had spent the previous decade as clueless Catherines, gazing dumbly from our carriages at the Potemkin village of Oslo.

So the Deira did negligible business, except after a noteworthy killing or a particularly sanguinary riot, which is the specialty of the heaving, thirsty demi-state of Gaza. Then, the press corps would colonize the Deira; reporters would come to catalogue the dead, and slot the deaths into whatever cleanly explicable narrative was in current favor.

The hallway was dim, and empty. I went downstairs to a veranda overlooking the Mediterranean, which shimmered in the early sunlight. Arab fishing boats spread their nets across the smooth water. An Israeli gunboat cast a more distant shadow. My breakfast companion was waiting for me. He rose, and we kissed on both cheeks. His nom de guerre was Abu Iyad, and he was an unhappy terrorist who I hoped would share with me illuminating gossip about Hamas—of which he was a member—and Palestine Islamic Jihad, two fundamentalist Muslim groups whose institutional focus is the murder of Jews. I bought him a plate of hummus and cucumbers.

Abu Iyad was a thin man, his face hollow and creased. His nails were yellow, and his hair was gray and thinning. I had known him for a dozen years. We weren’t friends. We were more like companionable acquaintances; I could not be a true friend of anyone in Hamas. He had been a bomb-maker earlier in his career, but he no longer submitted himself to the group’s hard line. His personality wasn’t that of the typical Hamas ultra. The average Hamas man tends toward narcis- sism and humorlessness, and projects the sort of preternatural calm organic to people who believe that what follows death is exponentially better than what precedes it. But Abu Iyad seemed, on occasion, free of certitude, taking a jaundiced view of some of his more strident colleagues. He only tentatively endorsed the notion, common among Hamas theologians, that the Jews live under a cloud of divine displeasure. He was well-educated—Soviet-educated, but still—and he was cultured, for Hamas. He was familiar with Camus and he was partial to Russian literature, though not to Russians. We often talked about books. Once, we spent an afternoon on the beach, near Nusseirat, his refugee camp, eating watermelon and talking about, of all things, the nihilism in Fathers and Sons.

It was a year before the second Intifada, our day at the beach. The strip of gray sand was the property, in essence, of Hamas; each political faction ruled a stretch of Mediterranean seaside. The Hamas cabanas were rude concrete slabs, topped with green flags that read, “There Is No God but Allah,” and “Muhammad Is the Messenger of God.” A crust of garbage lay over the beach, which was frequently used as a bathroom by donkey and man alike, but a breeze pushed the smell of shit away from us. The few women on the beach sat separate from the men. They wore black hijabs of thick cloth, head-to-foot, and they boiled inside them like eggs. Even when the women went to the water, they went in hijab. They waded in, up to their knees, splashed each other, and giggled. I could tell from the eyes, and the turn of their ankles, that they were pretty. I steered my own eyes away, though; even an innocent glance could have a terminal effect on me.

One of the men with us was a terrorist named Jihad Abu Swerah, a typically inflamed Hamas killer. He believed that the company of any women at all was an affront, even women who were serving us food. “Women by their presence pollute everything,” he said. A real killjoy. He reminded me of something the Ayatollah Khomeini once said: “There is no fun in Islam.”

Abu Swerah would eventually die at the hands of Israeli soldiers, who would find him in 2003 and cut him down in his Nusseirat hideout.

We tried to ignore him. Abu Iyad and I talked amiably on the beach that day with a few of his friends. The sky was soft blue and the water was gentle. It seemed to me an opportune time to throw an apple of discord into the circle. Just to make the day interesting, I accused Hamas—and the Muslim Brotherhood movement that gave birth to it—of succumbing to the temptations of nihilism.

ME: The Islamists believe in nothing except their own power. This frees them from the constraints of morality, allowing everything.

ABU IYAD: No, we believe in one surpassing truth, in tawhid, the cosmic Oneness of God. This is an overpowering belief. A nihilist, on the other hand, believes in nothing.

ME: This is true, in theory, the Islamist does believe in something. But that something is the supremacy of death, not the supremacy of God’s love. No one, not even Turgenev’s Bazarov is perfect in his nihilism. But Hamas comes close.

ABU IYAD: Jews fear death, Muslims don’t. Death isn’t even death. It’s a beginning. Love and death are both manifestations of God.

ME: You can’t murder people and say you’ve done them a favor.

ABU IYAD: Hamas does not target the innocent.

After the chastising Abu Swerah and his janissaries left, Abu Iyad allowed that the actions of Hamas bombers could be seen as nihilistic, which is why he said he opposed some of the more bestial manifestations of his group’s ideology. The men of Hamas, he said, sadly, were not his sort of Muslim. It was a victory for me, Abu Iyad ceding the point.

Sometimes, I couldn’t quite believe in his apostasy. His distaste for Hamas orthodoxy seemed real enough, but I sensed that it grew from some apolitical vendetta. Hamas, like any well-established terrorist group, is a bureaucracy, and, as in any bureaucracy, there are winners and losers, and I got the sense that he had lost—what, I didn’t know.

There was something else, too: Every so often, when we talked, he would pare off the edge of his words, speak in euphemism, even deny what I knew he felt. The Shi’ites call this taqiyya, the dissimulation of faith, the concealment of belief in the interest of self-preservation, or temporal political advantage. Sacramental lying, in other words. I worried that the face of Abu Iyad I saw was only one in a repertoire of faces. He did, after all, kill a man once.

The man was a Palestinian, his own blood, but a “collaborator” with Israel; Abu Iyad killed the man with a knife, in an alley in Nusseirat. Abu Iyad only remembered the man’s first name, which was Mustafa, and he remembered that he was taller than most Palestinians.

But then there were times when I stopped watching Abu Iyad through a veil of distrust, when I thought him to be a decent man, content to search for imperfect justice, not the world-ending justice sought by Hamas.

In the early 1990s, he favored, in principle, the murder of Israelis, in particular soldiers and settlers. But in November 2000, a group of Palestinians detonated a mortar shell near an armored bus traveling between two Jewish settlements, not far from Gaza City. Two settlers were killed, and three small children—all of the same family—lost limbs. This was unacceptable to Abu Iyad.

“It’s not the children who are at fault,” he said, an uncommon thing to say in Gaza, where children are both victim and perpetrator. Abu Iyad did not believe, for reasons both expedient and theological, that the slaughter of Israelis in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem would be helpful to his cause, and he questioned whether God smiled on the self-immolating assassins of Hamas. “A person can’t be pure and admitted to Paradise if he kills himself, is my belief. There is a lot of debate about this among the scholars.”

He sensed, even then, at breakfast, that the second Uprising, which was just beginning, would end badly for the Palestinians.

“The Israelis are too strong, and they’re too ready to use violence against us,” he said.

Nonsense, I said. Things will end badly for the Arabs because it is the Arabs who see violence as a panacea.

We went in circles on the question: Which side in this fight speaks more fluently the language of violence? I argued for the Arabs, and cited, as proof, a statement made to me not long before this breakfast by Abdel Aziz Rantisi, one of the founders of Hamas. Rantisi was a sour and self-admiring man, a pediatrician by trade, but one so perverse that he would work his rage on children. “The Israelis always say, when they kill our children, that they are sorry,” he told me. “When we kill Jewish children we say we are happy. So I ask you, who is telling the truth?”

And I mentioned to Abu Iyad something said to me by Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the so-called spiritual leader of Hamas, when I saw him at his home a few days earlier. I asked the sheikh about the three Israeli children on the bus, their limbs torn from them by a Palestinian bomb.

“They shouldn’t have been on holy Muslim land,” Sheikh Yassin said, his calm unperturbed by the thought of bleeding children. “This is what happens. The Jews have no right to life here. Their state was created in defiance of God’s will. This is in the Quran.”

I had no patience for Yassin. The thinking of scriptural fundamentalists seems, to the secular-minded, or even to the sort of person like me who feels the constant presence of God in his life but does not believe Him to be partisan in His love, as lunacy on stilts. It is also cruel beyond measure. Fundamentalism is the thief of mercy. These men, I told Abu Iyad, feel no human feelings at all.

Don’t be so dramatic, he said, in so many words. “The sheikh is just saying this because this is what reporters want to hear.” Dream murders, he suggested, do not constitute policy. They are to be understood as the last refuge of men stripped of all dignity.

“Well, it’s pathetic,” I said.

Abu Iyad asked, “It’s the way you feel about the Germans, right?”

I didn’t answer. I could have told him the truth: I was born, to my sorrow, too late to kill Germans. I could have said many other things, but I wasn’t going to argue the point with a man who thinks the Shoah, the Holocaust, was a trifle compared to the dispossession of the Palestinians.

“Sometimes, I feel very satisfied when a Jew gets killed,” he confessed. “I’m telling you what’s in my heart. It gives me a feeling of confidence. It’s very good for our people to know that they have the competence to kill Jews. So that is what Sheikh Yassin is saying.”

So you build your self-esteem through murder?

You misunderstand me, Abu Iyad said. Sheikh Yassin, he explained, was not typical of the Palestinian people; he succumbed to the temp- tation of violence too easily. The sheikh represented one side of the divided Arab heart, the side hungry for blood. The other side craves peace, even with the Jews.

Abu Iyad was a fundamentalist, hard where the world is soft, but he was also soft where the world is hard.

I am not the only Jew who divides the gentile world into two camps: the gentiles who would hide me in their attics when the Germans come; and the gentiles who would betray me to the death squads. I thought, on occasion, that Abu Iyad might be the sort to hide me.

I was late for an appointment, and so I excused myself copiously. I did not want to offend Abu Iyad, who, like his brother-Palestinians, was as sensitive as a seismograph to rudeness.

It was not an appointment I was keen to keep. I was meant to visit a Palestinian police base that had been rocketed by the Israeli Air Force the night before. I was reporting a story, and the drudgery of reporting is the repetition, going back again and again to see things I had already seen, in the naïve hope that I would finally see something different, or, at the very least, understand it more deeply. But in the first months of the Intifada, I saw Palestinian cars rocketed by Israeli helicopters, as well as Palestinian police stations, government offices, and apartment buildings. I saw blue-skinned corpses on slabs in the morgue, and children whose jaws and hands and feet were ripped away by missiles. I was familiar with the work of Israeli rockets.

The base belonged to Force 17, the personal bodyguard unit of Yasser Arafat. My regular taxi driver, a man called Abu Ibrahim, delivered me there. Abu Ibrahim means “Father of Abraham.” His given name was something else, which he seldom used since his wife gave birth to a son he called Ibrahim. He asked me once if I was father to a son. I said yes. He was relieved, on my behalf. I have two daughters as well, I said. But you have a son, he said, reassuring me. He could not pronounce my son’s name, so he called me “Abu Walad,” “Father of a Boy.”

He wasn’t much of a talker, in any case. He wouldn’t tell me that he was a killer. Fifteen years before, he murdered an agent of the Shabak, the Israeli internal security service. He lured the agent to an orange grove, and there he killed him, with a grenade.

That’s a great name you have, I told Abu Ibrahim once. There’s peace in that name: Jews, Christians, Muslims, all of us are sons of Abraham. He just grunted.

He was a hard man. He never smiled, and his arms were roped with prison muscle. I don’t think he cared about anything. Years before, I had learned from one of the chattier members of the Gambino organized crime family the expression menefreghismo, which means, roughly, “the art of not giving a fuck.” Abu Ibrahim was an adept of menefreghismo; its practitioners were scattered about in the occupied territories. Once, in Hebron, I watched a Palestinian man, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, approach an Israeli soldier and stab him in the chest. The cigarette stayed between his lips through the attack. That’s menefreghismo.

Gaza City is a compressed jumble of four- and five-story concrete apartment buildings, built at illogical angles on streets that are sometimes paved and sometimes not. Suddenly, out of the tangle, the Force 17 base appeared. It was a modest place—a few barracks, a parade ground, single-stor...

THE THIEF OF MERCY

On the morning of the fine spring day, full of sunshine, that ended with my arrest in Gaza, I woke early from an uneven sleep, dressed, and pushed back to its proper place the desk meant to barricade the door of my hotel room. I unknotted the bedsheets I had tied together into an emergency escape ladder. Then I hid the knife I kept under my pillow, cleaned the dust from my shoes, and carefully unbolted the door. I searched the dark hall. There were no signs of imminent peril. Most people wouldn’t be so cautious, but I had my reasons, and not all of them were rooted in self-flattering paranoia.

I was staying at the al-Deira hotel, a fine hotel, one of Gaza’s main charms. On hot nights, which are most nights, it brimmed over with members of haute Palestine, that small clique of Gazans who earned more than negligible incomes. The men smoked apple-flavored tobacco from water pipes; the women, their heads covered, drank strong coffee and kept quiet.

By day the hotel was mostly empty. The hotels of Gaza had been full in the 1990s, during the long moment of false grace manufactured by the Oslo peace process. In 1993, Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat shook hands on the White House lawn, and it seemed as if the hate would melt away like wax. At that moment, even a pessimist could envision an orderly close to the one-hundred-year-long war between Arab and Jew. But this was now the spring of 2001, and we were six months inside the Palestinian Uprising, the Intifada, the second Intifada, this one far more grim than the last. The land between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan was once again steeped in blood: Arabs were killing Jews, and Jews were killing Arabs, and hope seemed to be in permanent eclipse. Optimists, and I included myself in this category, felt as if we had spent the previous decade as clueless Catherines, gazing dumbly from our carriages at the Potemkin village of Oslo.

So the Deira did negligible business, except after a noteworthy killing or a particularly sanguinary riot, which is the specialty of the heaving, thirsty demi-state of Gaza. Then, the press corps would colonize the Deira; reporters would come to catalogue the dead, and slot the deaths into whatever cleanly explicable narrative was in current favor.

The hallway was dim, and empty. I went downstairs to a veranda overlooking the Mediterranean, which shimmered in the early sunlight. Arab fishing boats spread their nets across the smooth water. An Israeli gunboat cast a more distant shadow. My breakfast companion was waiting for me. He rose, and we kissed on both cheeks. His nom de guerre was Abu Iyad, and he was an unhappy terrorist who I hoped would share with me illuminating gossip about Hamas—of which he was a member—and Palestine Islamic Jihad, two fundamentalist Muslim groups whose institutional focus is the murder of Jews. I bought him a plate of hummus and cucumbers.

Abu Iyad was a thin man, his face hollow and creased. His nails were yellow, and his hair was gray and thinning. I had known him for a dozen years. We weren’t friends. We were more like companionable acquaintances; I could not be a true friend of anyone in Hamas. He had been a bomb-maker earlier in his career, but he no longer submitted himself to the group’s hard line. His personality wasn’t that of the typical Hamas ultra. The average Hamas man tends toward narcis- sism and humorlessness, and projects the sort of preternatural calm organic to people who believe that what follows death is exponentially better than what precedes it. But Abu Iyad seemed, on occasion, free of certitude, taking a jaundiced view of some of his more strident colleagues. He only tentatively endorsed the notion, common among Hamas theologians, that the Jews live under a cloud of divine displeasure. He was well-educated—Soviet-educated, but still—and he was cultured, for Hamas. He was familiar with Camus and he was partial to Russian literature, though not to Russians. We often talked about books. Once, we spent an afternoon on the beach, near Nusseirat, his refugee camp, eating watermelon and talking about, of all things, the nihilism in Fathers and Sons.

It was a year before the second Intifada, our day at the beach. The strip of gray sand was the property, in essence, of Hamas; each political faction ruled a stretch of Mediterranean seaside. The Hamas cabanas were rude concrete slabs, topped with green flags that read, “There Is No God but Allah,” and “Muhammad Is the Messenger of God.” A crust of garbage lay over the beach, which was frequently used as a bathroom by donkey and man alike, but a breeze pushed the smell of shit away from us. The few women on the beach sat separate from the men. They wore black hijabs of thick cloth, head-to-foot, and they boiled inside them like eggs. Even when the women went to the water, they went in hijab. They waded in, up to their knees, splashed each other, and giggled. I could tell from the eyes, and the turn of their ankles, that they were pretty. I steered my own eyes away, though; even an innocent glance could have a terminal effect on me.

One of the men with us was a terrorist named Jihad Abu Swerah, a typically inflamed Hamas killer. He believed that the company of any women at all was an affront, even women who were serving us food. “Women by their presence pollute everything,” he said. A real killjoy. He reminded me of something the Ayatollah Khomeini once said: “There is no fun in Islam.”

Abu Swerah would eventually die at the hands of Israeli soldiers, who would find him in 2003 and cut him down in his Nusseirat hideout.

We tried to ignore him. Abu Iyad and I talked amiably on the beach that day with a few of his friends. The sky was soft blue and the water was gentle. It seemed to me an opportune time to throw an apple of discord into the circle. Just to make the day interesting, I accused Hamas—and the Muslim Brotherhood movement that gave birth to it—of succumbing to the temptations of nihilism.

ME: The Islamists believe in nothing except their own power. This frees them from the constraints of morality, allowing everything.

ABU IYAD: No, we believe in one surpassing truth, in tawhid, the cosmic Oneness of God. This is an overpowering belief. A nihilist, on the other hand, believes in nothing.

ME: This is true, in theory, the Islamist does believe in something. But that something is the supremacy of death, not the supremacy of God’s love. No one, not even Turgenev’s Bazarov is perfect in his nihilism. But Hamas comes close.

ABU IYAD: Jews fear death, Muslims don’t. Death isn’t even death. It’s a beginning. Love and death are both manifestations of God.

ME: You can’t murder people and say you’ve done them a favor.

ABU IYAD: Hamas does not target the innocent.

After the chastising Abu Swerah and his janissaries left, Abu Iyad allowed that the actions of Hamas bombers could be seen as nihilistic, which is why he said he opposed some of the more bestial manifestations of his group’s ideology. The men of Hamas, he said, sadly, were not his sort of Muslim. It was a victory for me, Abu Iyad ceding the point.

Sometimes, I couldn’t quite believe in his apostasy. His distaste for Hamas orthodoxy seemed real enough, but I sensed that it grew from some apolitical vendetta. Hamas, like any well-established terrorist group, is a bureaucracy, and, as in any bureaucracy, there are winners and losers, and I got the sense that he had lost—what, I didn’t know.

There was something else, too: Every so often, when we talked, he would pare off the edge of his words, speak in euphemism, even deny what I knew he felt. The Shi’ites call this taqiyya, the dissimulation of faith, the concealment of belief in the interest of self-preservation, or temporal political advantage. Sacramental lying, in other words. I worried that the face of Abu Iyad I saw was only one in a repertoire of faces. He did, after all, kill a man once.

The man was a Palestinian, his own blood, but a “collaborator” with Israel; Abu Iyad killed the man with a knife, in an alley in Nusseirat. Abu Iyad only remembered the man’s first name, which was Mustafa, and he remembered that he was taller than most Palestinians.

But then there were times when I stopped watching Abu Iyad through a veil of distrust, when I thought him to be a decent man, content to search for imperfect justice, not the world-ending justice sought by Hamas.

In the early 1990s, he favored, in principle, the murder of Israelis, in particular soldiers and settlers. But in November 2000, a group of Palestinians detonated a mortar shell near an armored bus traveling between two Jewish settlements, not far from Gaza City. Two settlers were killed, and three small children—all of the same family—lost limbs. This was unacceptable to Abu Iyad.

“It’s not the children who are at fault,” he said, an uncommon thing to say in Gaza, where children are both victim and perpetrator. Abu Iyad did not believe, for reasons both expedient and theological, that the slaughter of Israelis in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem would be helpful to his cause, and he questioned whether God smiled on the self-immolating assassins of Hamas. “A person can’t be pure and admitted to Paradise if he kills himself, is my belief. There is a lot of debate about this among the scholars.”

He sensed, even then, at breakfast, that the second Uprising, which was just beginning, would end badly for the Palestinians.

“The Israelis are too strong, and they’re too ready to use violence against us,” he said.

Nonsense, I said. Things will end badly for the Arabs because it is the Arabs who see violence as a panacea.

We went in circles on the question: Which side in this fight speaks more fluently the language of violence? I argued for the Arabs, and cited, as proof, a statement made to me not long before this breakfast by Abdel Aziz Rantisi, one of the founders of Hamas. Rantisi was a sour and self-admiring man, a pediatrician by trade, but one so perverse that he would work his rage on children. “The Israelis always say, when they kill our children, that they are sorry,” he told me. “When we kill Jewish children we say we are happy. So I ask you, who is telling the truth?”

And I mentioned to Abu Iyad something said to me by Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the so-called spiritual leader of Hamas, when I saw him at his home a few days earlier. I asked the sheikh about the three Israeli children on the bus, their limbs torn from them by a Palestinian bomb.

“They shouldn’t have been on holy Muslim land,” Sheikh Yassin said, his calm unperturbed by the thought of bleeding children. “This is what happens. The Jews have no right to life here. Their state was created in defiance of God’s will. This is in the Quran.”

I had no patience for Yassin. The thinking of scriptural fundamentalists seems, to the secular-minded, or even to the sort of person like me who feels the constant presence of God in his life but does not believe Him to be partisan in His love, as lunacy on stilts. It is also cruel beyond measure. Fundamentalism is the thief of mercy. These men, I told Abu Iyad, feel no human feelings at all.

Don’t be so dramatic, he said, in so many words. “The sheikh is just saying this because this is what reporters want to hear.” Dream murders, he suggested, do not constitute policy. They are to be understood as the last refuge of men stripped of all dignity.

“Well, it’s pathetic,” I said.

Abu Iyad asked, “It’s the way you feel about the Germans, right?”

I didn’t answer. I could have told him the truth: I was born, to my sorrow, too late to kill Germans. I could have said many other things, but I wasn’t going to argue the point with a man who thinks the Shoah, the Holocaust, was a trifle compared to the dispossession of the Palestinians.

“Sometimes, I feel very satisfied when a Jew gets killed,” he confessed. “I’m telling you what’s in my heart. It gives me a feeling of confidence. It’s very good for our people to know that they have the competence to kill Jews. So that is what Sheikh Yassin is saying.”

So you build your self-esteem through murder?

You misunderstand me, Abu Iyad said. Sheikh Yassin, he explained, was not typical of the Palestinian people; he succumbed to the temp- tation of violence too easily. The sheikh represented one side of the divided Arab heart, the side hungry for blood. The other side craves peace, even with the Jews.

Abu Iyad was a fundamentalist, hard where the world is soft, but he was also soft where the world is hard.

I am not the only Jew who divides the gentile world into two camps: the gentiles who would hide me in their attics when the Germans come; and the gentiles who would betray me to the death squads. I thought, on occasion, that Abu Iyad might be the sort to hide me.

I was late for an appointment, and so I excused myself copiously. I did not want to offend Abu Iyad, who, like his brother-Palestinians, was as sensitive as a seismograph to rudeness.

It was not an appointment I was keen to keep. I was meant to visit a Palestinian police base that had been rocketed by the Israeli Air Force the night before. I was reporting a story, and the drudgery of reporting is the repetition, going back again and again to see things I had already seen, in the naïve hope that I would finally see something different, or, at the very least, understand it more deeply. But in the first months of the Intifada, I saw Palestinian cars rocketed by Israeli helicopters, as well as Palestinian police stations, government offices, and apartment buildings. I saw blue-skinned corpses on slabs in the morgue, and children whose jaws and hands and feet were ripped away by missiles. I was familiar with the work of Israeli rockets.

The base belonged to Force 17, the personal bodyguard unit of Yasser Arafat. My regular taxi driver, a man called Abu Ibrahim, delivered me there. Abu Ibrahim means “Father of Abraham.” His given name was something else, which he seldom used since his wife gave birth to a son he called Ibrahim. He asked me once if I was father to a son. I said yes. He was relieved, on my behalf. I have two daughters as well, I said. But you have a son, he said, reassuring me. He could not pronounce my son’s name, so he called me “Abu Walad,” “Father of a Boy.”

He wasn’t much of a talker, in any case. He wouldn’t tell me that he was a killer. Fifteen years before, he murdered an agent of the Shabak, the Israeli internal security service. He lured the agent to an orange grove, and there he killed him, with a grenade.

That’s a great name you have, I told Abu Ibrahim once. There’s peace in that name: Jews, Christians, Muslims, all of us are sons of Abraham. He just grunted.

He was a hard man. He never smiled, and his arms were roped with prison muscle. I don’t think he cared about anything. Years before, I had learned from one of the chattier members of the Gambino organized crime family the expression menefreghismo, which means, roughly, “the art of not giving a fuck.” Abu Ibrahim was an adept of menefreghismo; its practitioners were scattered about in the occupied territories. Once, in Hebron, I watched a Palestinian man, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, approach an Israeli soldier and stab him in the chest. The cigarette stayed between his lips through the attack. That’s menefreghismo.

Gaza City is a compressed jumble of four- and five-story concrete apartment buildings, built at illogical angles on streets that are sometimes paved and sometimes not. Suddenly, out of the tangle, the Force 17 base appeared. It was a modest place—a few barracks, a parade ground, single-stor...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPicador

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 033048818X

- ISBN 13 9780330488181

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages200

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 102.96

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Prisoners, a Muslim and Jew Across the Middle East Divide

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_033048818X

Buy New

US$ 102.96

Convert currency

Prisoners, a Muslim and Jew Across the Middle East Divide

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard033048818X

Buy New

US$ 104.32

Convert currency

Prisoners, a Muslim and Jew Across the Middle East Divide

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think033048818X

Buy New

US$ 250.90

Convert currency

Prisoners, a Muslim and Jew Across the Middle East Divide

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover033048818X

Buy New

US$ 253.96

Convert currency