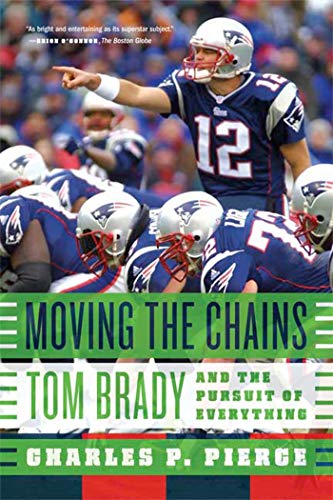

Items related to Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Synopsis

When Tom Brady entered the 2005 NFL season as lead quarterback for the New England Patriots, the defending Super Bowl champions, he was hailed as the best to ever play the position. And with good reason: he was the youngest quarterback to ever win a Super Bowl; the only quarterback in NFL history to win three Super Bowls before turning twenty-eight; the fourth player in history to win multiple Super Bowl MVP awards. He started the season with a 57–14 record, the best of any NFL quarterback since 1966.

Award-winning sports journalist Charles P. Pierce's Moving the Chains explains how Brady reached the top of his profession and how he stays there. It is a study in highly honed skills, discipline, and making the most of good fortune, and is shot through with ironies―a sixth-round draft pick turned superstar leading a football dynasty that was once so bedraggled it had to play a home game in Birmingham, Alabama, because no stadium around Boston would have it. It is also about an ordinary man and an ordinary team becoming extraordinary. Pierce interviewed Brady's friends, family, coaches, and teammates. He interviewed Brady (notably for Sports Illustrated's 2005 Sportsman of the Year cover article). And then he got the one thing he needed to truly take Brady's measure: 2005 turned out to be the toughest Patriots season in five years.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

On the staff of The Boston Globe Sunday Magazine and a regular panelist on NPR's It's Only a Game, Charles P. Pierce has written for, among others, Sports Illustrated, GQ, and Esquire. He is the author of two books.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Two Drives, Three Faces

The instructor was not optimistic. He was looking at a roomful of knuckleheads.

There were a couple of hockey players, and there were four or five baseball players—always the worst, a sense of entitlement on them as thick as pine tar on a bat. There were a handful of football players. There even were ten unsuspecting students unaffiliated with any of the university’s teams. This was a composition class at the University of Michigan, but it was stratifying by attitude into an unruly homeroom from some god-awful high school in the land of Beavis and Butt-head.

The instructor wasn’t theorizing from the faculty lounge, sherry and contempt dripping from his lips. Eight years earlier, he’d been one of them, a scholarship offensive lineman, a grunt in the service of Big Blue, a cog in an athletic combine that had entertained more than 40 million people since the first Wolverine team went 1–0–1 in 1879. He’d sat in classes like this. He had bullied the teachers. He had blown off the reading. He’d been a dumb jock. Looking back, he thought himself a thug.

Elwood Reid was a football apostate. He’d come to Michigan from the same high school in Cleveland that produced Elvis Grbac, a quarterback who’d thrown for 6,480 yards at Michigan and had helped win the 1993 Rose Bowl over Washington before moving on to a career in the NFL. Reid arrived in Ann Arbor bursting with words and ideas, and they’d proven to be stronger in him than the pull of a sport that seemed to have little use for either one. A sport that had left him, as he put it in a magazine piece years after leaving Michigan, “with this clear-cut of a body.”

Ultimately, Reid would turn his years at Michigan into a novel, If I Don’t Six. It was a roman for which no clef was necessary. Its hero, named Elwood Riley, is a freshman offensive lineman at Michigan with a jones for Marcus Aurelius. His gradual disillusionment with football is the story’s arc.

“They don’t show the bumps and bruises on television,” the fictional Elwood Reid says at one point, “or the long practices, cortisone needles as big as tenpenny nails, the yelling, and hours of boring film meetings where you watch the same play a dozen times until the coach feels that when you go home and close your eyeballs, the play’s going to be running on the back of your eyelids.”

So Reid knew what he was looking at in his classroom full of knuckleheads. He was looking at a kind of fun-house mirror in time, where the years bent and showed him the reflection of the person football had tried to make of him. The person he’d never be.

Reid noticed the skinny quarterback right off. He didn’t dress the way the other jocks did—a style that could generously be described as workout casual. The quarterback was polite. He was sincere. “He’d read the material that I didn’t give a shit about in that class when I took it,” Reid recalls.

What was even more interesting to Reid was the reaction of the other jocks in the class. He’d seen the really heartbreaking ones—the ones who established their own territory through a kind of armored ignorance. Not only did they not do the reading, but they were also conspicuously proud that they hadn’t, and openly contemptuous of anyone who had. “They make fun of you,” Reid muses. “That’s the way they cull you from the herd.”

The quarterback was different. He spoke differently. He even brought his books to class. Reid figured that the knuckleheads would eat him alive. He thought, at best, the quarterback would get himself a reputation around Ann Arbor as a kind of dropback Eddie Haskell. At worst, he’d get his ass kicked, literally and figuratively, for the rest of his college career.

For good and ill, football is a great leveler. In no other sport is the balance between personal achievement and collective accomplishment so exquisitely delicate. In no other sport is the conflict between the two so consistently volatile. In football, it’s a dangerous business to stand out in the wrong way.

To Reid’s surprise, even the most disruptive guys in the class did more than leave the quarterback alone. They seemed to look up to him. In fact, they seemed to look up to him more because he wasn’t following their lead. “The pull of the pack is to act a certain way,” Reid says. “And he wouldn’t do it. He took things seriously, and he was very gracious, so I figured, here was a guy who was going to go through the [football] program and then go find a life for himself.

“I said to myself, look at this guy. I’m going to help this guy. I want to open his eyes. So I made sure he read all the essays. I was a little harder on him than I was on the other guys. I told him to pay attention in class, because that’s the thing that I didn’t do.”

Five years later, in 2002, the skinny quarterback led the New England Patriots to a shocking win in the Super Bowl over the St. Louis Rams. Two years later, he did it again, this time over the Carolina Panthers. The next year, he did it a third time, defeating the Philadelphia Eagles. He became football’s biggest star. He became celebrated for his ability to stand out at the top of his profession while maintaining an almost fundamentalist belief in being a teammate.

It was very strange to see played out on a vast stage the same thing that had happened in that classroom full of knuckleheads, thought Elwood Reid. It was very strange to see what had become of the kid who always brought his books to class and who never was given any shit about it, even from the people who—whether they knew it or not—already were dedicating their lives to giving shit to people about things like that. Because there was something about him that connected. Because there was something about this Brady character that was real.

“I remember that class,” Tom Brady said, leaning against a fence one summer’s day, as the New England Patriots rounded into the last weeks of training camp before the 2005 season. They had won two consecutive Super Bowls and were preparing to try to win their third, securing the team’s place even more firmly as one of the greatest in the history of the National Football League, and Brady even more firmly in the ranks of the league’s greatest quarterbacks.

Over the previous four years, Brady had been the Patriots’ starting quarterback, and, in two of the three Super Bowls that they’d won, he’d been the Most Valuable Player. In that time, the team won twenty-one consecutive regular-season games, an NFL record. This success was all the more remarkable given the history of the Patriots, once so lost and bedraggled a franchise that they were forced to play a home game in Birmingham, Alabama, because no stadium around Boston would have them.

Now, though, the team drew thousands of people just to watch it train at its facility outside Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, an otherwise sleepy little town south of Boston, just about on the upper bicep where Massachusetts flexes itself into Cape Cod. They showed up, in the height of the high summer, more than 52,000 of them a week, to watch football practice, which, on its most exciting day, can fairly be said to make the main reading room of the Boston Public Library look like Mardi Gras.

They showed up, and the young girls screamed for Tom Brady the same way the fifty-year-old men did, except the pitch was higher. On the field, the team moved through its drills, grouped by position and then all together. Whenever a player, or a group of players, made a mistake, he had to run a lap around the entire field. When the various miscreants passed a grassy knoll that rises behind one end zone of the practice field, the fans sprawled thickly on the grass gave the passing screwups a standing ovation. Nothing the New England Patriots did was wrong, not even the things that were, well, wrong.

Unlike basketball, where people scrimmage, or baseball’s spring training, which involves playing actual games, nobody who comes to football training camp actually sees anyone play a game of football. “When I was playing lacrosse in high school,” the New England head coach, Bill Belichick, once recalled, “I couldn’t wait for practice because I got to play lacrosse. Football practice isn’t like that.” Instead, football players train in crushing heat in order to perform in shattering cold. They t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0374214441

- ISBN 13 9780374214449

- BindingPaperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00056649500

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00073061884

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0374214441-3-26425034

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0374214441-3-27343772

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0374214441-3-26425034

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00066769303

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Good. First Edition. Corners are slightly bent. Used - Good. Seller Inventory # 11-F-2-0132

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: Blue Vase Books, Interlochen, MI, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Seller Inventory # 31UI5600E83S_ns

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.7. Seller Inventory # G0374214441I2N00

Quantity: 1 available

Moving the Chains: Tom Brady and the Pursuit of Everything

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.7. Seller Inventory # G0374214441I4N00

Quantity: 1 available