Synopsis

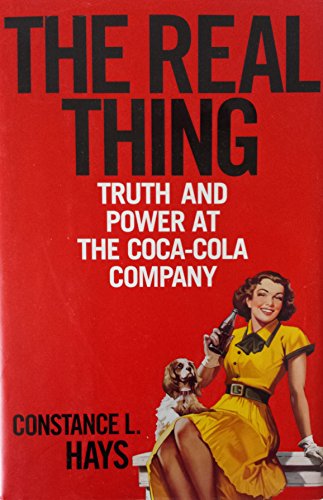

A definitive history of Coca-Cola, the world’s best-known brand, by a New York Times reporter who has followed the company and who brings fresh insights to the world of Coke, telling a larger story about American business and culture

The Real Thing is a portrait of America’s most famous product and the men who transformed it from mere soft drink to symbol of freedom. The story, starting with Coke’s creation after the Civil War and continuing with its domination of the domestic and worldwide soft-drink business, is a uniquely American tale of opportunity, hope, teamwork, and love, as well as salesmanship, hubris, ambition, and greed. By 1920, the Coca-Cola Company’s success depended on a unique partnership with a group of independent bottlers. Together, they had made Coke not just a soft drink but an element of our culture. But the company, intent on controlling everything about Coke, did all it could to dismantle that partnership. In its reach for power, it was more than willing to gamble the past.

Constance L. Hays examines a century of Coca-Cola history through the charismatic, driven men who used luck, spin, and the open door of enterprise to turn a beverage with no nutritional value into a remedy, a refreshment, and the world’s best-known brand. The story of Coke is also a catalog of carbonation, soda fountains, dynastic bottling businesses, global expansion, and outsize promotional campaigns, including New Coke, one of the greatest marketing debacles of all time. By examining relationships at all levels of the company, The Real Thing reveals the psyche of a great American corporation and how it shadows all business, for better or worse.

This is as much a story about America as it is the tale of a great American product, one recognized all over the world. Under the leadership of Roberto Goizueta and Doug Ivester, Coca-Cola reinvented itself for investors, spearheading trends such as lavish executive salaries and the wooing of Wall Street, but when Coke’s great global ambitions ran into trouble, it had difficulty getting back on track.

The Real Thing is a journey through the soft-drink industry, from the corner office to the vending machine. It is also a social history in which sugared water becomes an international object of consumer desire—and the messages poured upon an eager public gradually obscure the truth.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Constance L. Hays has worked as a reporter for The News and Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina, and, since 1986, for The New York Times, where she covered the food and beverage industry for three years. She lives in New York City with her husband, John A. Hays, and their three children.

From the Inside Flap

<i>A definitive history of Coca-Cola, the world’s best-known brand, by a </i>New York Times<i> reporter who has followed the company and who brings fresh insights to the world of Coke, telling a larger story about American business and culture</i><br><br><b>The Real Thing</b> is a portrait of America’s most famous product and the men who transformed it from mere soft drink to symbol of freedom. The story, starting with Coke’s creation after the Civil War and continuing with its domination of the domestic and worldwide soft-drink business, is a uniquely American tale of opportunity, hope, teamwork, and love, as well as salesmanship, hubris, ambition, and greed. By 1920, the Coca-Cola Company’s success depended on a unique partnership with a group of independent bottlers. Together, they had made Coke not just a soft drink but an element of our culture. But the company, intent on controlling everything about Coke, did all it could to dismantle that partnership. In its reach for power, it was more than willing to gamble the past.<br><br>Constance L. Hays examines a century of Coca-Cola history through the charismatic, driven men who used luck, spin, and the open door of enterprise to turn a beverage with no nutritional value into a remedy, a refreshment, and the world’s best-known brand. The story of Coke is also a catalog of carbonation, soda fountains, dynastic bottling businesses, global expansion, and outsize promotional campaigns, including New Coke, one of the greatest marketing debacles of all time. By examining relationships at all levels of the company, <b>The Real Thing</b> reveals the psyche of a great American corporation and how it shadows all business, for better or worse.<br><br>This is as much a story about America as it is the tale of a great American product, one recognized all over the world. Under the leadership of Roberto Goizueta and Doug Ivester, Coca-Cola reinvented itself for investors, spearheading trends such as lavish executive salaries and the wooing of Wall Street, but when Coke’s great global ambitions ran into trouble, it had difficulty getting back on track.<br> <br><b>The Real Thing</b> is a journey through the soft-drink industry, from the corner office to the vending machine. It is also a social history in which sugared water becomes an international object of consumer desire―and the messages poured upon an eager public gradually obscure the truth.

Reviews

Hays, who spent three years covering the food and beverage industry for the New York Times, focuses on the recent efforts by Coca-Cola not just to win the cola wars but to become the most dominant beverage of all. Early chapters effectively segue back and forth between Coke's modern global strategy and the company's first century of increasing dominance. Founder Asa Candler envisioned Coke as a fountain drink, and thought so little of other sales methods he gave two men bottling rights to nearly all of America in 1899, resulting in a patchwork of plants where the sodas was made and distributed. Hays deftly shows how these local bottlers were crucial in establishing Coke's public image, yet often possessed an independent streak that rankled the company's corporate leaders, who eventually sought to regain control over much of the operations, with mixed results. She clearly admires the ambition and dedication of executives like Roberto Goizeuta and Doug Ivester, allowing much of the story to unfold from their perspective, but doesn't flinch from chronicling missteps like the attempt to beat the Pepsi Challenge with New Coke. And even though the final chapters depict the shattering of the Coke myth and the onset of financial woes, it's sometimes difficult to tell whether Hays is simply reporting on the new management's belief in its ability to bounce back or buying into their vision. Readers won't uncover the secrets of Coca-Cola the drink, but they'll learn a lot about what lies behind Coca-Cola the world's most powerful brand.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Hays, a reporter who followed Coca-Cola for five years, tells the story of the soft drink company that has come to be viewed throughout the world as an American icon. The corporate giant had a modest start in 1886, serving its distinctive product only at soda fountains. The emergence of independent bottlers changed the business--and the world--forever as bottles and bright red dispensing machines made their way around the globe, from urban centers to dusty villages. Hays offers engaging profiles of the different powerful personalities who have run the company, also covering its spectacular successes and failures (the marketing debacle of New Coke is particularly noteworthy). But although this corporate history is very interesting, many will question the book's objectivity: Coca-Cola is a master of public relations, and the book was written with the blessing of the company's management. Mary Whaley

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter One

The Road to Rome On a bright fall morning in 1994, Doug Ivester, the recently anointed president of the Coca-Cola Company, was driving himself to Rome, Georgia, spinning north along the interstate, the steel-and-glass towers of Atlanta receding behind him as the landscape became an uneven blanket of pines.

Ivester had his day all planned out. Like plenty of Coke executives before him, he had a certain fixation with Hollywood—the glitter, the lights, the adjustable distance between image and reality. And now he was going to star in his own short film, which he had already named The Road to Rome.

He had borrowed a sport-utility vehicle and hired a camera crew. Husky and hawk-nosed, he had dressed down for the occasion in a V-neck sweater and left his usual silk necktie at home. He aimed the boxy car toward Rome, pulling over every so often at all kinds of places to ask whether they served Coca-Cola.

It became an exercise in frustration, if you happened to be the second-highest-ranking executive at the company that owned the Coca-Cola brand. The cameras trailed Ivester at every stop, recording the scene at a karate studio where the flustered owner apologetically explained before the inquiring lens that he didn’t sell Coke, and at the Kennesaw Mountain tourist attraction, where there was no Coke, either. In his reedy North Georgia twang, Ivester kept asking everyone in his path the same apparently simple question: What if people coming to these places wanted a Coke? What if they finished training for their black belt, looked around for a way to quench their thirst, and realized there was no place nearby to get their hands on a Coke?

There was only one right answer in the script that he had dictated: They’d be disappointed. So would hundreds, no, millions of other people across the globe, in all of the other places where Coke still wasn’t for sale in every possible nook that it could be sold. The message of the film—that even right in its own backyard, a place presumably already saturated with Coke, the Coca-Cola Company still had plenty of room to grow—was an ongoing theme inside the company. And Ivester was going to make sure Coke got every last bit of that growth.

There would be no Oscars for The Road to Rome, which was completed on a modest budget that year and screened before limited audiences—Wall Street analysts mostly, and here and there a Coke bottler. But it was remarkable nevertheless, articulating something beyond the typical corporate statement of purpose. It was a graphic guide to the mentality of the Coca-Cola Company and the mind of the man who now occupied its second-highest position: a man who believed fervently and unremittingly in the supremacy of Coca-Cola.

That the drink was more than a century old and was still not being sold absolutely everywhere hounded Ivester. People close to him claimed that he could not sleep at night if he knew that a store somewhere in the depths of the nation, any nation, was not selling Coca-Cola. Maybe it was the pizza parlor in Omaha that Warren Buffett, the legendary investor and Coke director, visited one day with his grandson, only to report back that it served nothing but Pepsi. Ivester made it his personal project to get the Pepsi out and the Coca-Cola in; within weeks, he had made the change. Maybe it was a country like Vietnam, where for years American business had been prohibited. Awaiting the day the embargo might end, Ivester had a plane loaded with Cokes and signs and other equipment intended to capture the new market. In 1994, a few hours after the State Department gave American companies the green light to invest again in Vietnam, the Coke plane took off. It was on a mission to restore the business that politics had inconveniently halted almost twenty years earlier.

Like many of the people at his company, Ivester had a relentless faith in the drink’s appeal for people of all ages, races, cultures, and economic profiles. To him, if Coke was on the shelf, or in the vending machine, or in the dispenser down at the 7-Eleven, then that’s what people would buy. But still, even in tried-and-true Coke country, like the hills of Georgia—the part of America where Ivester himself grew up—there were plenty of places that didn’t stock it. And the key to filling in all those holes, to completing the program put forth by legions of Coke men culminating with Ivester, was to seal the gaps between the Coca-Cola Company and its historically feisty and independent bottling system.

The Coca-Cola Company was 108 years old on the morning that Ivester set off for Rome, and it was already the biggest soft-drink company in the world. Nineteen ninety-four was its greatest year yet. People drank Coca-Cola morning, noon, and night in the United States, where Coke had gotten started. In many places Coca-Cola stood in for coffee as the way people began their day. It had replaced milk and fruit juice in many lunchboxes, even in baby bottles in some places, if everything you heard was true. Ivester liked to predict that one day, along with red wine and water goblets, a formal table setting would have to include a broad-shouldered Coca-Cola glass.

That was just one of Ivester’s goals. And he usually got what he wanted. Over the previous decade, he had transformed Coke from a nodding institu- tion into a sleek and ultra-competitive global champion, envied and imitated by dozens of other American companies. Along with two colleagues, Roberto Goizueta and Donald Keough, he had created a monolith that tapped skillfully into emerging markets and pumped unexpected growth out of old ones. They had turned a well-known brand-name soda into a money machine, an ice-veined fountain jingling with cash. As Ivester drove along the road to Rome, Coca-Cola was the best-known product in the world. The company was selling Coke at the rate of 850 million eight-ounce bottles a day, or 310 billion bottles a year. Stacked one on top of another, a year’s worth of global Coke sales would create a tower reaching nearly all the way to Mars. Fourteen months of sales would get you all the way there.

But that was not enough for Ivester.

Like Goizueta, he wanted the consumption of Coke to keep on growing. Now that Keough had retired, it was just the two of them, and they aggressively promoted the company’s prospects, touting the opportunities to sell ever more Coca-Cola worldwide before an impressed Wall Street. The Coca-Cola Company was all about growth, the men of Coke insisted. With close to a billion servings sold every day, they believed that the company had only just begun to make its mark in the world. Two billion servings were just around the corner.

They made these kinds of promises publicly, and they programmed their company to fulfill them. They had kept those promises again and again over the previous thirteen years, posting spectacular gains in sales and in earnings, beating not just the competition but most of the rest of industrial America, as well. Ivester’s movie was really just another reminder, in case anyone needed reminding, not to underestimate Coke.

So complete was their obsession that these men were tormented by the way Coca-Cola remained a distant also-ran to other beverages in many parts of the globe. It was not just a matter of vanquishing Pepsi-Cola; it was also about beating back drinks like coffee, tea, milk, and water. In fly-blown, malnourished parts of Asia and Africa, people still—inexplicably, if you asked Ivester—preferred tea or juice to Coca-Cola. In France, people might buy three kinds of bottled water in their supermarkets—and, incredibly, pass up the red cans of Coca-Cola. If Coke could capture those markets, persuading consumers to drink cola instead, then the brand would grow even more. That was what Ivester and Goizueta wanted. That was what their planning was all about.

They wanted Coca-Cola everywhere. In refrigerated cases in convenience stores, out on the street in barrels packed with ice, in vending machines in school hallways, in the basements and pantries of people’s houses, and on tap at restaurants, ball parks, movie theaters, hotels, cruise ships, and all the other places where people spend their time. When a person drove into a gas station, they wanted him to think Coke first. When somebody stood in a movie line and had to choose something to drink during the 7:15 show, they wanted it to be Coke. They wanted Coke to be available every time somebody felt a stab of thirst. And, whenever possible, they wanted it to be the only beverage on the shelf.

To the two men who held the top jobs at Coke in 1994, this was not some eccentric, highly personal approach to commerce. It was the cornerstone of their business plan. They told people like Warren Buffett about it, and he applauded them, despite the risks. “In given countries at given times there will be hiccups,” Buffett would say. “But that doesn’t take your eye off where you want to be ten or fifteen years from now, which is to have everybody drink nothing but Coke.” They had made their promises to people like him. They were going to make them come true.

Year by year, Ivester and Goizueta invested a lot in the outcome. For the more Coke people consumed, the more money would flow into the Coca-Cola Company, which produced the concentrate—a dark, sticky, undrinkable ooze—that became the soda. More money meant greater profits, which would lift the stock price, making all the people who had invested in it—the grannies in Atlanta; the great capitalists in New York, Los Angeles, and Omaha; and, not least, the grand executives of Coke, their accounts bulging with stock options, restricted stock, and ordinary stock—wealthier with every day that went by.

To Ivester, careful planning was critical to making sure that happened. He saw potential in microscopic terms. He started with his employees, all 29,000 of them around the world. It was th...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Fast Free Shipping â" Good condition book with a firm cover and clean, readable pages. Shows normal use, including some light wear or limited notes highlighting, yet remains a dependable copy overall. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # GWV.0375505628.G

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00087337414

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0375505628I4N00

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0375505628I4N01

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0375505628I4N00

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0375505628I4N00

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_445576856

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_446875681

The Real Thing: Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # S21D-02359

The Real Thing : Truth and Power at the Coca-Cola Company

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1st. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 9448280-6