Items related to Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinar...

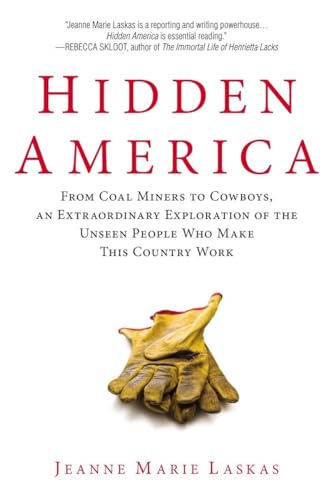

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work - Softcover

Award-winning journalist Jeanne Marie Laskas reveals “enlightening, entertaining, and often poignant”* profiles of America's working class—the forgotten men and women who make our country run.

Take the men of Hopedale Mining company in Cadiz, Ohio. Laskas spent several weeks with them, both below and above ground, and by the end, you will know not only about their work, but about Pap and his dying mom, Smitty and the mail-order bride who stood him up at the airport, and Scotty and his thwarted dreams of becoming a boxing champion.

That is only one hidden world. Others that she explores: an Alaskan oil rig, a migrant labor camp in Maine, the air traffic control center at LaGuardia Airport in New York, a beef ranch in Texas, a landfill in California, a long-haul trucker in Iowa, a gun shop in Arizona, and the Cincinnati Ben-Gals cheerleaders, mere footnotes in the moneymaking spectacle that is professional football.

“Jeanne Marie Laskas is a reporting and writing powerhouse. She doesn’t just interview the people who dig our coal and extract our oil, she goes deep into the mines and tundra with them. With beauty, wit, curiosity, and grace, she finds the hidden soul of America. Hidden America is essential reading.”—Rebecca Skloot, author of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Laskas writes regularly for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and GQ, where she is a correspondent. She is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, where she is director of The Writing Program, and founding director of The Center for Creativity. She lives on a horse farm with her husband and two daughters.

Puente Hills Landfill

City of Industry, California

Herman asks me if I smell anything, and the way he says it I can’t tell if I’m supposed to lie. He says he loves being part of nature, enjoys watching the sunrise, and

then he says it again. “Do you smell anything?”

“Well, it is a landfill,” I say, finally. I’m trying to be polite. He is old, wiry, chewing a toothpick. He’s been at this for decades, always the first to arrive, pulling no. 72, the thirty-foot-long tractor-trailer full of trash assigned to him each day. Dumping is permitted to begin at 6:00 a.m., and he keeps his finger on a red button inside a panel on the truck and constantly checks his watch.

“Women smell things men can’t smell,” he says.

At this hour the landfill looks nothing like what most people picture when they imagine a landfill. Nothing messy, nothing gross, nothing slimy, no trash anywhere at all. It looks, perhaps disappointingly, like an enormous, lonesome construction site, a 1,365-acre expanse of light brown dirt hiding buried trash from yesterday and thousands of other yesterdays. The scale of the thing alone boggles the mind. To stop and ponder the fact that nearly fifty years of trash forms a foundation four hundred feet deep is simply to become fretful with some unnamed woe about America’s past and the planet’s future, and so I am trying not to do it. When fellow truckers arrive, pulling up next to Herman, the ground—so deep with trash—is so soft it bounces.

The Puente Hills Landfill, about sixteen miles east of downtown Los Angeles, was a series of canyons when people first started dumping here. Now it’s a mountain. In 1953 the film adaptation of H. G. Wells’s science fiction novel The War of the Worlds featured the Puente Hills as the landing site of the first spacecraft in the Martian invasion. Dumping started in 1965 in an area named the San Gabriel Valley Dump. In 1970 the dump was purchased by the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County, a partnership of twenty-four independent districts serving five million people in seventy-eight cities in Los Angeles County, and renamed the Puente Hills Landfill. Every day 13,200 new tons of trash are added. That’s enough trash to fill a one-acre hole twenty feet deep. The other way to look at it is a football stadium filled two stories high.

On November 1, 2013, the landfill will be out of room, and all that trash will have to go somewhere else.

At six o’clock, Herman pushes the button. The back end of the trailer rises and 79,650 pounds of debris comes thundering out, most of it wood and plaster and nails and shreds of wallpaper. Be- side him a truck is dumping decidedly more organic garbage, pun- gent indeed, and way down the row, off to the side, a guy is pouring a truck full of sludge, sterilized human waste, black as ink.

Herman gets a broom, sweeps his trailer clean. Unlike most of

the haulers who come here—the guys who drive for the conglomerates like Waste Management with their continuous fleet of shiny green packers—Herman works for the Sanitation Districts itself, moving trash from a central dumping station in the nearby town of Southgate. Thus, his priority status. He will make five trips in a day, stopping only once to eat Oodles of Noodles and cheese crackers and a cookie. On the ride home, he eats a green apple. “I’ve got my routine,” he says. “Every day I do it all exactly the same.” He talks to me about his philosophy of slowing down, not making mistakes, same way every day, the power of ritual. Peaceful. Using this method, he worked his way up from paper picker, day laborer, traffic director, water truck diver, on and on until he found his niche. There is honor, he says, in being first each day, all those other trucks parting at the gate so Herman can get through. He is careful to note that he is the only one of his entire eighth-grade graduating class of 1954 who has not yet retired. “Why would anyone retire from a place like this?” he asks. “Why would you?”

Having spent more than a week at the landfill, by now I am get- ting used to hearing workers here, from the highest to the lowest ranks, speak like this. Concerning the landfill, they are all pride and admiration and even thanks. It seemed, at first, like crazy talk.

A landfill, after all, is a disgusting place. It is not a place anyone should have to work in, or see, or smell. This is a 100-million-ton solid soup of diapers, Doritos bags, phone books, shoes, carrots, watermelon rinds, boats, shredded tires, coats, stoves, couches, Biggie fries, piled up right here off the I-605 freeway. It’s a place that smells like every dumpster you ever walked by—times a few hundred thousand. It’s a place that brings to mind the hell of civilization, a heap of waste and ugliness and everything denial is designed for. We throw stuff out. The stuff is supposed to go away. Disappear. We tend not to think about the fact that every time we throw a moist towelette or an empty Splenda packet or a Little Debbie snack cake wrapper into the trash can, there are people involved, a whole chain of people charged with the preposterously complicated task of making that thing vanish—which it never really does. A landfill is not something we want to bother thinking about, and if we do, we tend to blame the landfill itself for sitting there stinking like that, for marring the landscape, for offending a sanitized aesthetic. We are human, highly evolved creatures impatient with all things stinky and gooey and gross— remarkably adept at forgetting that a landfill would be nothing, literally nothing, without us.

In America, we produce more garbage than any other country in the world: four pounds per person each day, for a total of 250 million tons a year. In urban areas, we are running out of places to put all that trash. Right now, the cost of getting rid of it is dirt cheap—maybe $15 a month on a bill most people never even see, all of it wrapped into some mysterious business about municipal tax revenue. So why think about it?

Electricity used to be cheap too. We went for a long time not thinking about the true cost of that. Same with gas for our cars.

The problem of trash (and sewage, its even more offensive cousin) is the upside-down version of the problem of fossil fuel: too much of one thing, not enough of the other. Either way, it’s a mat- ter of managing resources. Either way, a few centuries of gorging and not thinking ahead has the people of the twenty-first century standing here scratching our heads. Now what?

The problem of trash, fortunately, is a wondrously provocative puzzle to scientists and engineers, some of whom lean, because of the inexorability of trash, toward the philosophical. The intrinsic conundrum—the disconnect between human waste and the human himself—becomes grand, even glorious, to the people at the dump. “I brought my wife up here once to show her,” Herman tells me. “I said, ‘Look, that’s trash.’ She couldn’t believe it. Then she couldn’t understand it. I told her, I said, ‘This is the Rolls-Royce of landfills.’ ”

“Nobody knows we’re even here,” Joe Haworth is saying as we make our way around the outside of the landfill, winding up and up past scrubby California oaks, sycamore trees, and the occasional shock of pink bougainvillea vine. He is driving his old Cadillac, a

1982 Eldorado, rusty black with a faded KERRY-EDWARDS sticker on the bumper. He has the thick glasses of a civil engineer, which is how he started, and the curls and paunch and demeanor of a crusty retired PR man, which is what he is now. He wears a Hawaiian print shirt and a straw hat, and the way he leans way back in the driver’s seat suggests an easy, uncomplicated confidence.

“People driving by on the highway think this is a park,” he says. “Or they’ll be, like, ‘What’s with all the pipes going around that mountain?’ ”

In fact, we are driving over trash, a half century’s worth, a heap so vast, there are roads and stop signs and traffic cops and a his- tory of motor vehicle accidents, including at least one fatality.

The outside of the landfill, the face the public sees, reminds me of Disney World, a perfectly crafted veneer of happiness belying a vastly more complicated core. The western side, facing the 605, is lush greens and deep blues, a showy statement of desert defiance, while the eastern face is quiet earth tones, scrubby needlegrass, buttonbush, and sagebrush; the native look on that side was re- quested by the people living in Hacienda Heights, a well-to-do neighborhood in the foothills of the dump. They wanted the mountain of trash behind them to blend in with the canyons reaching toward the sunset. A staff of fifty landscapers do nothing but honor such requests. The goal: Make the landfill disappear by making it look pretty.

“No matter what you do with your trash, nature has to process it,” Joe is saying. “Okay? Think about it.” We are making our way up to a lookout point where we can get an overview of the action of the trash trucks and bulldozers and scrapers, a good show and a good place to sit and think. Joe speaks with rapid-fire speed, constantly punctuating his lessons with Groucho Marx–style asides. “Look, we’d be up to our eyeballs in dinosaur poop if nature didn’t have any way to run this stuff around again,” he says. He loves this stuff. He is sixty-four years old, an environmental engineer, a Jesuit-trained fallen Catholic whose enthusiasm for waste management, solid, liquid, recycled, buried, burning, de- composing, is oddly infectious. I have come to regard him as the high priest of trash.

“Instead of being up to our eyeballs in dinosaur poop, we’re made of dinosaur poop,” he says. “You know? And other chemicals. We’ve got garbage in us. There’s a carbon cell from Napoleon in your elbow somewhere. It’s all nature running things around again, a continuous loop. It’s all done by bacteria breaking it down into carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, okay? Think about it!”

I tell him I’ll add it to my list, which keeps getting longer the longer I’m here. Joe retired from the landfill a couple of years ago, but he comes back to consult, to visit, to help Donny, his assistant who took over his job, and to sit and marvel. He entered the refuse world back in the 1960s, when people first awakened, as if from a lazy daydream, to the notion that trash not only matters but trash is matter, and matter never leaves. You can burn it. You can bury it. You can throw it into the ocean. You can try to hide it, but it still exists in some form: ash, sludge, gas, particulate matter floating in the air. “It all comes back to the idea of the cycle,” he says. “We’re going to keep reusing the same stuff, so let’s figure out how to use it responsibly so we don’t choke on it.”

He gives me an example. “See those pipes?” he says, pointing as we cruise up the landfill. “Those are sucking gas.” The pipes are fat and prominent, about two feet in diameter, and a constant source of wild wonder. Eighty miles of pipes encircle the landfill, pulling out a deadly mix of methane, carbon dioxide, and other gases continuously produced by the fermenting trash. The pipes are connected with seventy-five miles of underground trenches and to a network of fourteen hundred wells. The methane mix is highly explosive and smelly and in the past has been an environmental nightmare. As trash continues to ferment, the methane is unstoppable. And so the pipes—a kind of landfill miracle, a technology pioneered by Sanitation Districts engineers—deliver the methane downhill to the Gas-to-Energy Facility. The methane feeds a boiler, creates steam. The steam turns a turbine. The turbine generates fifty-eight megawatts of electricity—enough to power about seventy thousand Southern California homes.

Before I started hanging out at the landfill, I had no idea we could generate electricity from trash. “Most people don’t know this,” I say to Joe.

“Oh, a lot of people know it,” he says.

No, they don’t. I have checked. I have consulted folks back home, regular trash makers, average citizens going through cartons of Hefty bags, who think little beyond “Gotta take the trash out” when it comes to the final resting place of their garbage. “People don’t know we power homes with landfill gas,” I say. “Don’t you think people should know this?”

He looks at me, weary. “Why do you think I’ve been busting my ass at this for thirty years, lady?”

He blinks, removes his glasses, takes out a handkerchief, and wipes them clean. “That’s what I did,” he says. “I did nothing but tell people about what we do here. Now, how much time does society have to listen and understand? Well, the answer to that is, society’s interest level is pretty low. It doesn’t necessarily want to know where its waste goes. It’s embarrassed by its responsibility in this arena.”

Joe parks the car and we get out. We stand and peer down into the landfill, at trash, the very stuff Herman and his fellow truckers dumped earlier this morning. From this distance, the open landfill is a giant brown five-hundred-acre bowl, with a frantic line of trucks inside snorting and pregnant and awaiting release.

This is the cheapest place to dump trash in all of L.A. County, about $28 a ton, and so it is the first choice of most garbage companies. When the landfill reaches its 13, 200-ton daily capacity, usually by about noon, the guard at the gate will raise a flag visible from the freeway: a sign to truckers to keep on moving and find another place to dump. Anyone can dump here, any private citizen with a pickup full of junk willing to pay the fee.

Trash gets piled in as many as three active areas, or “cells,” daily. Each cell is about the size of a football field, and every hour an additional 1,200 tons of trash is put into it. A team of thirty heavy-equipment operators dances madly over the pile. Huge bull- dozers, ten feet tall, equipped with seventeen-foot blades, push and sculpt the trash into rows. Then the mighty Bomags, 120,000- pound compactors with 130,000 pounds of pushing power, smash and crunch and squish the trash, forcing out air, forcing it tighter and tighter to save space. All of these machines clamber impossibly close to one another, backward, forward, over steep hills of trash, clinging lopsidedly to edges. From up here, the sounds are...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBerkley

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 042526727X

- ISBN 13 9780425267271

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 2.64

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Hidden America : From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 19360681-n

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work by Laskas, Jeanne Marie [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780425267271

Hidden America Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 042526727X

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work

Book Description Paper Back. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 304869

Hidden America

Book Description Condition: New. pp. 336. Seller Inventory # 2697244506

Hidden America

Book Description Condition: New. pp. 336. Seller Inventory # 96234117

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_042526727X

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon042526727X

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard042526727X

Hidden America: From Coal Miners to Cowboys, an Extraordinary Exploration of the Unseen People Who Make This Country Work

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 042526727X-2-1