Items related to Sandalwood Tree

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

1947

Our train hurtled past a gold-spangled woman in a mango sari, regal even as she sat in the dirt, patting cow dung into disks for cooking fuel. A sweep of black hair obscured her face and she did not look up as the passing train shook the ground under her bare feet. We barreled past one crumbling, sun-scorched village after another, and the farther we got from Delhi the more animals we saw trudging alongside the endless swarm of people—arrogant camels, humpbacked cows, bullock-drawn carts, goats and monkeys, and suicidal dogs. The people walked slowly, balancing vessels on their heads and bundles on their backs, and I stared like a rude tourist, vaguely ashamed of my rubbernecking—they were just ordinary people, going about their lives, and I sure as hell wouldn’t like someone staring at me, at home in Chicago, as if I were some bizarre creature on exhibit—but I couldn’t look away.

The train stopped for a cow on the tracks, and a suppurating leper hobbled up to our window, holding out a fingerless hand. My husband, Martin, passed a coin out the window while I distracted Billy with an impromptu rib-tickle. I blocked his view of the leper with my back to the window and smiled gamely as he pulled up his little knees and folded in on himself, giggling. “No fair,” he gasped. “You didn’t warn me.”

“Warn you?” I wiggled two fingers in his soft armpit and he squealed. “Warn you?” I said. “Where’s the fun in that?” We wrestled merrily until, minutes later, the train ground to life and we pulled away, leaving the leper behind, salaaming in his gray rags.

Last year, early in 1946, Senator Fulbright had announced an award program for graduate students to study abroad, and Martin, a historian writing his Ph.D. thesis on the politics of modern India, won a scholarship to document the end of the British Raj. We arrived in Delhi at the end of March in 1947, about a year before the British were scheduled to depart India forever. After more than two hundred years of the Raj, the Empire had been faced down by a skinny little man in a loincloth named Gandhi and the Brits were finally packing it in. However, before they left they would draw new borders, arbitrary lines to partition the country between Hindus and Muslims, and a new nation called Pakistan would be born. Heady stuff for a historian.

Of course I appreciated the noble purpose behind the Fulbright—fostering a global community—and understood the seriousness of partition, but I had secretly dreamed about six months of moonlit scenes from The Arabian Nights. I was intoxicated by the prospect of romance and adventure and a new beginning for Martin and me, which is why I was not prepared for the grim reality of poverty, dung fires, and lepers—in the twentieth century?

Still, I didn’t regret coming along; I wanted to see the pageant that is Hindustan and to ferret out the mystery of her resilience. I wanted to know how India had managed to hold on to her identity despite a continuous stream of foreign conquerors slogging through her jungles and over her mountains, bringing their new gods and new rules, often setting up shop for centuries at a time. Martin and I hadn’t been able to hold on to the “us” in our marriage after one stint in one war.

I stared out of the open window, studying everything from behind my new sunglasses, tortoiseshell plastic frames with bottle-green lenses. Martin wore his regular glasses, which left him squinting in the savage Indian sun, but he said he didn’t mind; he didn’t even wear a hat, which I thought foolish, but he was stubborn about it. My dark-green lenses and my wide-brimmed, straw topee gave me a sense of protection, and I wore them everywhere.

We passed pink Hindu temples and white marble mosques, and I raised my new Kodak Brownie camera up to the window often, but didn’t see any hints of the ancient tension simmering between Hindus and Muslims—not yet—only the impression that everyone was struggling to survive. We passed mud-hut villages, inexplicable piles of abandoned bricks, shelters made from tarps draped haphazardly over bamboo poles, and fields of millet stretching away into mist.

The air smelled like smoke tinged with sweat and spices, and when gritty dust invaded our compartment, I closed the window, brought out the hairbrush, washcloth, and diluted rubbing alcohol that I carried in my hand baggage and went to work on Billy. He sat patiently as I whisked his clothes, wiped his face, and brushed his blond hair till it shone. By then the poor child had gotten used to my neurotic need for cleanliness, and if you understand the lunatic nuances involved in keeping up appearances you’ll understand why I spent an insane amount of time fighting dust and dirt in India.

I caught the madness from Martin. He had come home from the war in Germany obsessed with a need for calm and order, and by the time we had dragged ourselves halfway around the world to that untidy subcontinent I was cleaning compulsively, drowning confusion in soapy water, purging discontent with bleach and abrasive cleansers. When we arrived in Delhi, I shook out the bed linen on the tiny balcony of our hotel room before I let my weary husband and child go to sleep. In the narrow lanes of Old Delhi, crammed with people and rickshaws and wandering cows, I pinched my nose against the smell of garbage and urine and insisted Martin take us back to the hotel, where I checked under the bed and in the corners for spiders. Found a couple and smashed them flat—so much for karma.

When we boarded the train to go north, I wiped down the seats in our compartment with my ever-ready washcloth before I let Martin or Billy sit. Martin gave me a look that said, “Now you’re being ridiculous.” But the tyranny of obsession is absolute and will not be reasoned with. At every stop, chai-wallahs, water bearers, and food vendors leaped onto the train and sped through the carriages hawking biscuits, tea, palm juice, dhal, pakoras, and chapatis, and I recoiled from them, keeping a protective arm around Billy while shooting a warning look at Martin.

At the first few stops, mingled smells of grease and sweat saturated the sweltering air and made the food unappealing. But after several hours without eating, Martin suggested we try a few snacks. I quickly produced the hotel sandwiches I’d packed in Delhi and handed him one, agreeing only to buy three cups of masala chai—gorgeous, creamy tea infused with cloves and cardamom—because I knew it had been boiled. I ate my bacon sandwich and drank my tea, feeling safe and insulated—I would observe and understand India without India actually touching me. But, munching away and looking out the window, my heart beat faster at the sight of an elephant lumbering on the horizon. A mahout, straddling the massive neck, urged the animal along with his bare heels, and I watched, strangely exhilarated, until they disappeared in a trail of red dust.

Billy watched women walking along the side of the road with brass pots balanced on their heads and men bent double under enormous loads of grain. Often, ragged children straggled behind, looking thin and exhausted. Quietly, he asked, “Are those poor people, Mom?”

“Well, they’re not rich.”

“Shouldn’t we help them?”

“There are too many of them, sweetie.”

He nodded and stared out the window.

On our first day in Masoorla I threw open the blue shutters of our rented bungalow, beat the hell out of the dhurrie rugs, and polished all the scarred old furniture. I went over every inch of the old, two-bedroom house with carbolic soap and used a quart of Jeyes cleaning fluid in the bathroom. Martin said I should get a sweeper to do it, but how could I trust a woman who spent half her time up to her elbows in cow dung to clean my house? Anyway, I wanted to do it. I didn’t know how to fix my marriage, but I knew how to clean. Denial is the first refuge of the frightened, and it is possible to distract oneself by scrubbing, organizing, and covering smells of curry and dung with disinfectant. It works—for a while.

When I found the hidden letters, I had just finished an assault on the kitchen window. I squeezed out the sponge and stood back, squinting with a critical eye. A yellow sari converted to curtains framed the blue sky and distant Himalayan peaks, which were now clearly visible through the spotless window, but the late-afternoon sun spotlighted a dirty brick wall behind the old English cooker. The red brick had been blackened by a century of oily cooking smoke and, just like that, I decided to roll up my sleeves and give it a good scrub. Rashmi, our ayah, deigned to wipe off a table or sweep the floor with a bunch of acacia branches, but I would never ask her to tackle a soot-encrusted wall. A job like that fell well beneath her caste, and she would have quit on the spot.

The university chose that bungalow for us because it had an attached kitchen instead of the usual cookhouse out back. I liked the place as soon as I walked into the little compound full of tangled grass and pipal trees with creepers twisting around their trunks. A low mud-brick wall, overgrown with Himalayan mimosa, circled our compound with its hundred-year-old bungalow and vine-clad verandah, and an old sandalwood tree, with long oval leaves and pregnant red pods, presided over the front of the house. Everything had a weathered, well-used look, and I wondered how many lives had been lived there.

Off to one side of the house, a path bordered by scrappy boxwood led to the godowns for the servants, a dilapidated row of huts, far more of them than we would ever need for our small staff. At the far end of the godowns a derelict stable nestled in a grove of deodars, and Martin talked about using it to park our car during the monsoon. Martin had bought a battered and faded...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBLACK SWAN

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 0552775223

- ISBN 13 9780552775229

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages510

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Sandalwood Tree [Soft Cover ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780552775229

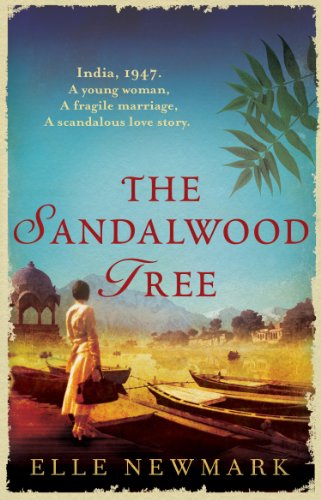

The Sandalwood Tree

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 512 pages. 7.80x5.00x1.26 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # zk0552775223

Newmark, E: The Sandalwood Tree

Book Description Condition: New. Dieser Artikel ist ein Print on Demand Artikel und wird nach Ihrer Bestellung fuer Sie gedruckt. It is 1947, and Evie and Martin Mitchell have just arrived in the Indian village of Masoorla with their five-year-old son. But cracks soon appear in their marriage as Evie struggles to adapt to her new life, and Martin fails to bury unbearable wartime memor. Seller Inventory # 594774308