Items related to Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished...

Propelled by his boyhood passion for the Civil War, Horwitz embarks on a search for places and people still held in thrall by America's greatest conflict. The result is an adventure into the soul of the unvanquished South, where the ghosts of the Lost Cause are resurrected through ritual and remembrance.

In Virginia, Horwitz joins a band of 'hardcore' reenactors who crash-diet to achieve the hollow-eyed look of starved Confederates; in Kentucky, he witnesses Klan rallies and calls for race war sparked by the killing of a white man who brandishes a rebel flag; at Andersonville, he finds that the prison's commander, executed as a war criminal, is now exalted as a martyr and hero; and in the book's climax, Horwitz takes a marathon trek from Antietam to Gettysburg to Appomattox in the company of Robert Lee Hodge, an eccentric pilgrim who dubs their odyssey the 'Civil Wargasm.'

Written with Horwitz's signature blend of humor, history, and hard-nosed journalism, Confederates in the Attic brings alive old battlefields and new ones 'classrooms, courts, country bars' where the past and the present collide, often in explosive ways. Poignant and picaresque, haunting and hilarious, it speaks to anyone who has ever felt drawn to the mythic South and to the dark romance of the Civil War.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

--Roy Blount Jr., New York Times Book Review

"In this sparkling book Horwitz explores some of our culture's myths with the irreverent glee of a small boy hurling snowballs at a beaver hat. . . . An important contribution to understanding how echoes of the Civil War have never stopped."

--USA Today

Horwitz's chronicle of his odyssey through the nether and ethereal worlds of Confederatemania is by turns amusing, chilling, poignant, and always fascinating. He has found the Lost Cause and lived to tell the tale a wonderfully piquant tale of hardcore reenactors, Scarlett O'Hara look-alikes, and people who reshape Civil War history to suit the way they wish it had come out. If you want to know why the war isn't over yet in the South, read Confederates in the Attic to find out.

--James McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom

The enthusiasm, opinions, and beliefs of latter-day Confederates don't get much mainstream exposure these days, but Tony Horwitz portrays them with accuracy, humor, and respect. This is a serious book on a serious subject, but it often made me laugh out loud. Like some characters from a Walker Percy novel, Horwitz keeps finding himself in utterly absurd settings, with colorful, even bizarre, companions.

--John Shelton Reed, author of Whistling Dixie: Dispatches from the South

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPantheon

- Publication date1998

- ISBN 10 0679439781

- ISBN 13 9780679439783

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages406

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

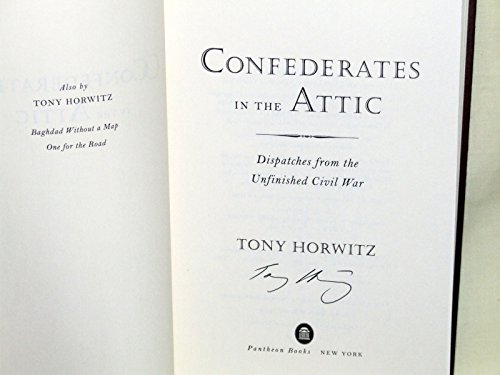

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0679439781

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0679439781xvz189zvxnew

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_0679439781

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0679439781-new

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0679439781

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0679439781

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0679439781

CONFEDERATES IN THE ATTIC : DISP

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.65. Seller Inventory # Q-0679439781

Confederates in the Attic : Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War

Book Description Condition: new. 1st. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. Seller Inventory # PSN0679439781