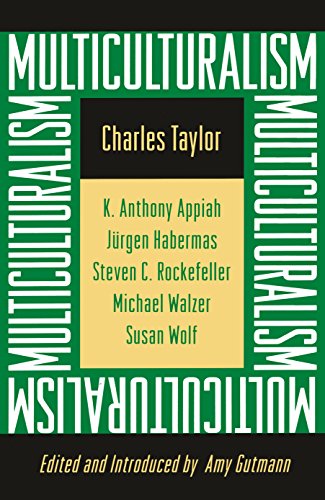

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition - Softcover

Book 1 of 16: University Center for Human Values

Synopsis

A new edition of the highly acclaimed book Multiculturalism and "The Politics of Recognition," this paperback brings together an even wider range of leading philosophers and social scientists to probe the political controversy surrounding multiculturalism. Charles Taylor's initial inquiry, which considers whether the institutions of liberal democratic government make room--or should make room--for recognizing the worth of distinctive cultural traditions, remains the centerpiece of this discussion. It is now joined by Jürgen Habermas's extensive essay on the issues of recognition and the democratic constitutional state and by K. Anthony Appiah's commentary on the tensions between personal and collective identities, such as those shaped by religion, gender, ethnicity, race, and sexuality, and on the dangerous tendency of multicultural politics to gloss over such tensions. These contributions are joined by those of other well-known thinkers, who further relate the demand for recognition to issues of multicultural education, feminism, and cultural separatism.

Praise for the previous edition:

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Charles Taylor is Professor of Philosophy and Political Science at McGill University; K. Anthony Appiah, Professor of Afro-American Studies and Philosophy at Harvard University; Jürgen Habermas, Professor of Philosophy at Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universitat, Frankfurt am Main; Steven C. Rockefeller, Professor of Religion at Middlebury College; Michael Walzer, Permanent Member of the Faculty at the School of Social Sciences at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton; Susan Wolf, Professor of Philosophy at The Johns Hopkins University; and Amy Gutmann, Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor of Politics and Director of the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University.

From the Back Cover

Charles Taylor's initial inquiry, which considers whether the institutions of liberal democratic government make room - or should make room - for recognizing the worth of distinctive cultural traditions, remains the centerpiece of this discussion. It is now joined by Jurgen Habermas's extensive essay on the issues of recognition and the democratic constitutional state and by K. Anthony Appiah's commentary on the tensions between personal and collective identities, such as those shaped by religion, gender, ethnicity, race, and sexuality, and the dangerous tendency of multicultural politics to gloss over such tensions.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Multiculturalism

EXAMINING THE POLITICS OF RECOGNITIONBy Charles Taylor K. Anthony Appiah Jürgen Habermas Steven C. Rockefeller Michael Walzer Susan WolfPRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Copyright © 1994 Princeton University PressAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-691-03779-0

Contents

Preface (1994).....................................................................................................................................ixPreface and Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................xiiiPART ONE...........................................................................................................................................1Introduction Amy Gutmann..........................................................................................................................3The Politics of Recognition Charles Taylor........................................................................................................25Comment Susan Wolf................................................................................................................................75Comment Steven C. Rockefeller.....................................................................................................................87Comment Michael Walzer............................................................................................................................99PART TWO...........................................................................................................................................105Struggles for Recognition in the Democratic Constitutional State Jürgen Habermas Translated by Shierry Weber Nicholsen.....................107Identity, Authenticity, Survival: Multicultural Societies and Social Reproduction K. Anthony Appiah...............................................149Contributors.......................................................................................................................................165Index..............................................................................................................................................169

Chapter One

The Politics of RecognitionCHARLES TAYLOR

I

A number of strands in contemporary politics turn on the need, sometimes the demand, for recognition. The need, it can be argued, is one of the driving forces behind nationalist movements in politics. And the demand comes to the fore in a number of ways in today's politics, on behalf of minority or "subaltern" groups, in some forms of feminism and in what is today called the politics of "multiculturalism."

The demand for recognition in these latter cases is given urgency by the supposed links between recognition and identity, where this latter term designates something like a person's understanding of who they are, of their fundamental defining characteristics as a human being. The thesis is that our identity is partly shaped by recognition or its absence, often by the misrecognition of others, and so a person or group of people can suffer real damage, real distortion, if the people or society around them mirror back to them a confining or demeaning or contemptible picture of themselves. Nonrecognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being.

Thus some feminists have argued that women in patriarchal societies have been induced to adopt a depreciatory image of themselves. They have internalized a picture of their own inferiority, so that even when some of the objective obstacles to their advancement fall away, they may be incapable of taking advantage of the new opportunities. And beyond this, they are condemned to suffer the pain of low self-esteem. An analogous point has been made in relation to blacks: that white society has for generations projected a demeaning image of them, which some of them have been unable to resist adopting. Their own self-depreciation, on this view, becomes one of the most potent instruments of their own oppression. Their first task ought to be to purge themselves of this imposed and destructive identity. Recently, a similar point has been made in relation to indigenous and colonized people in general. It is held that since 1492 Europeans have projected an image of such people as somehow inferior, "uncivilized," and through the force of conquest have often been able to impose this image on the conquered. The figure of Caliban has been held to epitomize this crushing portrait of contempt of New World aboriginals.

Within these perspectives, misrecognition shows not just a lack of due respect. It can inflict a grievous wound, saddling its victims with a crippling self-hatred. Due recognition is not just a courtesy we owe people. It is a vital human need.

In order to examine some of the issues that have arisen here, I'd like to take a step back, achieve a little distance, and look first at how this discourse of recognition and identity came to seem familiar, or at least readily understandable, to us. For it was not always so, and our ancestors of more than a couple of centuries ago would have stared at us uncomprehendingly if we had used these terms in their current sense. How did we get started on this?

Hegel comes to mind right off, with his famous dialectic of the master and the slave. This is an important stage, but we need to go a little farther back to see how this passage came to have the sense it did. What changed to make this kind of talk have sense for us?

We can distinguish two changes that together have made the modern preoccupation with identity and recognition inevitable. The first is the collapse of social hierarchies, which used to be the basis for honor. I am using honor in the ancien régime sense in which it is intrinsically linked to inequalities. For some to have honor in this sense, it is essential that not everyone have it. This is the sense in which Montesquieu uses it in his description of monarchy. Honor is intrinsically a matter of "préférences." It is also the sense in which we use the term when we speak of honoring someone by giving her some public award, for example, the Order of Canada. Clearly, this award would be without worth if tomorrow we decided to give it to every adult Canadian.

As against this notion of honor, we have the modern notion of dignity, now used in a universalist and egalitarian sense, where we talk of the inherent "dignity of human beings," or of citizen dignity. The underlying premise here is that everyone shares in it. It is obvious that this concept of dignity is the only one compatible with a democratic society, and that it was inevitable that the old concept of honor was superseded. But this has also meant that the forms of equal recognition have been essential to democratic culture. For instance, that everyone be called "Mr.," "Mrs.," or "Miss," rather than some people being called "Lord" or "Lady" and others simply by their surnames—or, even more demeaning, by their first names—has been thought essential in some democratic societies, such as the United States. More recently, for similar reasons, "Mrs." and "Miss" have been collapsed into "Ms." Democracy has ushered in a politics of equal recognition, which has taken various forms over the years, and has now returned in the form of demands for the equal status of cultures and of genders.

But the importance of recognition has been modified and intensified by the new understanding of individual identity that emerges at the end of the eighteenth century. We might speak of an individualized identity, one that is particular to me, and that I discover in myself. This notion arises along with an ideal, that of being true to myself and my own particular way of being. Following Lionel Trilling's usage in his brilliant study, I will speak of this as the ideal of "authenticity." It will help to describe in what it consists and how it came about.

One way of describing its development is to see its starting point in the eighteenth-century notion that human beings are endowed with a moral sense, an intuitive feeling for what is right and wrong. The original point of this doctrine was to combat a rival view, that knowing right and wrong was a matter of calculating consequences, in particular, those concerned with divine reward and punishment. The idea was that understanding right and wrong was not a matter of dry calculation, but was anchored in our feelings. Morality has, in a sense, a voice within.

The notion of authenticity develops out of a displacement of the moral accent in this idea. On the original view, the inner voice was important because it tells us what the right thing to do is. Being in touch with our moral feelings matters here, as a means to the end of acting rightly. What I'm calling the displacement of the moral accent comes about when being in touch with our feelings takes on independent and crucial moral significance. It comes to be something we have to attain if we are to be true and full human beings.

To see what is new here, we have to see the analogy to earlier moral views, where being in touch with some source—for example, God, or the Idea of the Good—was considered essential to full being. But now the source we have to connect with is deep within us. This fact is part of the massive subjective turn of modern culture, a new form of inwardness, in which we come to think of ourselves as beings with inner depths. At first, this idea that the source is within doesn't exclude our being related to God or the Ideas; it can be considered our proper way of relating to them. In a sense, it can be seen as just a continuation and intensification of the development inaugurated by Saint Augustine, who saw the road to God as passing through our own self-awareness. The first variants of this new view were theistic, or at least pantheistic.

The most important philosophical writer who helped to bring about this change was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. I think Rousseau is important not because he inaugurated the change; rather, I would argue that his great popularity comes in part from his articulating something that was in a sense already occurring in the culture. Rousseau frequently presents the issue of morality as that of our following a voice of nature within us. This voice is often drowned out by the passions that are induced by our dependence on others, the main one being amour propre, or pride. Our moral salvation comes from recovering authentic moral contact with ourselves. Rousseau even gives a name to the intimate contact with oneself, more fundamental than any moral view, that is a source of such joy and contentment: "le sentiment de l'existence."

The ideal of authenticity becomes crucial owing to a development that occurs after Rousseau, which I associate with the name of Herder—once again, as its major early articulator, rather than its originator. Herder put forward the idea that each of us has an original way of being human: each person has his or her own "measure." This idea has burrowed very deep into modern consciousness. It is a new idea. Before the late eighteenth century, no one thought that the differences between human beings had this kind of moral significance. There is a certain way of being human that is my way. I am called upon to live my life in this way, and not in imitation of anyone else's life. But this notion gives a new importance to being true to myself. If I am not, I miss the point of my life; I miss what being human is for me.

This is the powerful moral ideal that has come down to us. It accords moral importance to a kind of contact with myself, with my own inner nature, which it sees as in danger of being lost, partly through the pressures toward outward conformity, but also because in taking an instrumental stance toward myself, I may have lost the capacity to listen to this inner voice. It greatly increases the importance of this self-contact by introducing the principle of originality: each of our voices has something unique to say. Not only should I not mold my life to the demands of external conformity; I can't even find the model by which to live outside myself. I can only find it within.

Being true to myself means being true to my own originality, which is something only I can articulate and discover. In articulating it, I am also defining myself. I am realizing a potentiality that is properly my own. This is the background understanding to the modern ideal of authenticity, and to the goals of self-fulfillment and self-realization in which the ideal is usually couched. I should note here that Herder applied his conception of originality at two levels, not only to the individual person among other persons, but also to the culture-bearing people among other peoples. Just like individuals, a Volk should be true to itself, that is, its own culture. Germans shouldn't try to be derivative and (inevitably) second-rate Frenchmen, as Frederick the Great's patronage seemed to be encouraging them to do. The Slavic peoples had to find their own path. And European colonialism ought to be rolled back to give the peoples of what we now call the Third World their chance to be themselves unimpeded. We can recognize here the seminal idea of modern nationalism, in both benign and malignant forms.

This new ideal of authenticity was, like the idea of dignity, also in part an offshoot of the decline of hierarchical society. In those earlier societies, what we would now call identity was largely fixed by one's social position. That is, the background that explained what people recognized as important to themselves was to a great extent determined by their place in society, and whatever roles or activities attached to this position. The birth of a democratic society doesn't by itself do away with this phenomenon, because people can still define themselves by their social roles. What does decisively undermine this socially derived identification, however, is the ideal of authenticity itself. As this emerges, for instance, with Herder, it calls on me to discover my own original way of being. By definition, this way of being cannot be socially derived, but must be inwardly generated.

But in the nature of the case, there is no such thing as inward generation, monologically understood. In order to understand the close connection between identity and recognition, we have to take into account a crucial feature of the human condition that has been rendered almost invisible by the overwhelmingly monological bent of mainstream modern philosophy.

This crucial feature of human life is its fundamentally dialogical character. We become full human agents, capable of understanding ourselves, and hence of defining our identity, through our acquisition of rich human languages of expression. For my purposes here, I want to take language in a broad sense, covering not only the words we speak, but also other modes of expression whereby we define ourselves, including the "languages" of art, of gesture, of love, and the like. But we learn these modes of expression through exchanges with others. People do not acquire the languages needed for self-definition on their own. Rather, we are introduced to them through interaction with others who matter to us—what George Herbert Mead called "significant others." The genesis of the human mind is in this sense not monological, not something each person accomplishes on his or her own, but dialogical.

Moreover, this is not just a fact about genesis, which can be ignored later on. We don't just learn the languages in dialogue and then go on to use them for our own purposes. We are of course expected to develop our own opinions, outlook, stances toward things, and to a considerable degree through solitary reflection. But this is not how things work with important issues, like the definition of our identity. We define our identity always in dialogue with, sometimes in struggle against, the things our significant others want to see in us. Even after we outgrow some of these others—our parents, for instance—and they disappear from our lives, the conversation with them continues within us as long as we live.

Thus, the contribution of significant others, even when it is provided at the beginning of our lives, continues indefinitely. Some people may still want to hold on to some form of the monological ideal. It is true that we can never liberate ourselves completely from those whose love and care shaped us early in life, but we should strive to define ourselves on our own to the fullest extent possible, coming as best we can to understand and thus get some control over the influence of our parents, and avoiding falling into any more such dependent relationships. We need relationships to fulfill, but not to define, ourselves.

The monological ideal seriously underestimates the place of the dialogical in human life. It wants to confine it as much as possible to the genesis. It forgets how our understanding of the good things in life can be transformed by our enjoying them in common with people we love; how some goods become accessible to us only through such common enjoyment. Because of this, it would take a great deal of effort, and probably many wrenching break-ups, to prevent our identity's being formed by the people we love. Consider what we mean by identity. It is who we are, "where we're coming from." As such it is the background against which our tastes and desires and opinions and aspirations make sense. If some of the things I value most are accessible to me only in relation to the person I love, then she becomes part of my identity.

To some people this might seem a limitation, from which one might aspire to free oneself. This is one way of understanding the impulse behind the life of the hermit or, to take a case more familiar to our culture, the solitary artist. But from another perspective, we might see even these lives as aspiring to a certain kind of dialogicality. In the case of the hermit, the interlocutor is God. In the case of the solitary artist, the work itself is addressed to a future audience, perhaps still to be created by the work. The very form of a work of art shows its character as addressed. But however one feels about it, the making and sustaining of our identity, in the absence of a heroic effort to break out of ordinary existence, remains dialogical throughout our lives.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Multiculturalismby Charles Taylor K. Anthony Appiah Jürgen Habermas Steven C. Rockefeller Michael Walzer Susan Wolf Copyright © 1994 by Princeton University Press. Excerpted by permission of PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Search results for Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Cypress, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0691037795-3-24645144

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 0691037795-4-26372719

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition and has highlighting/writing on text. Used texts may not contain supplemental items such as CDs, info-trac etc. Seller Inventory # 00085502913

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: SustainableBooks.com, Amherst, NY, U.S.A.

Condition: Poor. Book is Poor condition. Good for reading, not pretty to look at! The pages and cover are soiled and/or yellowed, worn throughout. Seller Inventory # 0691037795-2-6

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: HPB-Emerald, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_377677390

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_432946915

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: Zoom Books East, Glendale Heights, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: very_good. Book is in very good condition and may include minimal underlining highlighting. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Seller Inventory # ZEV.0691037795.VG

Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition

Seller: Dream Books Co., Denver, CO, U.S.A.

Condition: acceptable. This copy has clearly been enjoyedâ"expect noticeable shelf wear and some minor creases to the cover. Binding is strong, and all pages are legible. May contain previous library markings or stamps. Seller Inventory # DBV.0691037795.A

Multiculturalism : Expanded Paperback Edition

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. (expanded) Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Seller Inventory # 3965871-6

Multiculturalism : Expanded Paperback Edition

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. (expanded) Edition. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Seller Inventory # 3965871-6