Items related to Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball...

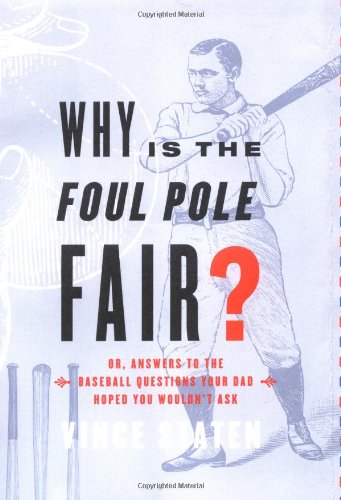

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask) - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter One: Take Me Out to the Ball Game

I grew up in a neighborhood of boys. Tony and Mike were on one side of my house, Darnell on the other, Lance in back, next to him Michael and Donnie and Bob, then Ronald and Billy, Phil and Eddie, across the street to Tommy, up the hill to Chip and Butch.

All you needed to do on a Saturday morning was take a bat and ball to the field, then start tossing up a few and hitting them; the crack of the bat was siren call enough. Soon, there were six, eight kids, gloves in hand, ready for a pickup game.

There was always a game going in my neighborhood: football in fall, basketball in winter, and baseball the rest of the time. We didn't have a real ball field; we cobbled one together from a couple of backyards, a vacant lot, a garden, and a dog pen. My backyard was the end zone in fall, the backcourt in winter, and the infield in spring. I remember a man whom my father worked with coming by and being greatly distressed at how we neighborhood boys had worn base paths into the grass. "Those boys are killing your yard," the man said. And I remember my father's answer. "Those boys will be gone someday. That grass will grow back."

.  .  .

I grew up loving baseball. When I wasn't playing it, I was watching it on TV or reading about it in the Sporting News, or talking about it with my best friend Lance Harris. He and I oiled our gloves together, we taped our bats together, and, on the days we couldn't get up a game, we played catch and pepper together.

The only thing we didn't do was go to games together. There was no team in our town, big-league or otherwise. There was a Class D Rookie League franchise twenty miles away, but the big leagues were as far away as my dream of someday playing there.

At the beginning of my eleventh summer, my father announced that we wouldn't be going to the beach that year. It had been a vacation tradition for as long as I could remember. "No, not this summer," he said. Instead, we were going to a big-league baseball game. Suddenly, I couldn't breathe. This might not seem like a big deal to a city kid but, to a southern boy in the fifties, this was better than finding out you'd made Little League all-stars. See, we had no big-league clubs in the South then. The Braves were still in Milwaukee, the Astros and Rangers and Marlins and Devil Rays were all off in the future.

On our way to the distant ballpark that summer we thread through the mountains into Kentucky, then up to Cincinnati for a Reds game against my favorite team, the Giants. I'll never forget that weekend. It was the longest car ride of my life.

It was the dog days of summer when we arrived at the Queen City of the Ohio. Cincinnati is a city that's notoriously humid in the summer, but who knows from humidity when you're a kid? We unpacked in a motel on the Kentucky side of the river, then hustled over to Findlay and Western Avenue, site of the now-legendary Crosley Field.

I loved the hustle and bustle outside my first big-league park. I loved the sounds of the sidewalk barkers hawking pennants and balls and every kind of baseball trinket. I loved the crush of people scurrying to the turnstiles. And, when we finally got through the mob, a Giants pennant in my hand, and hurried up the ramp to the plaza overlooking the field, I couldn't believe my eyes. I was finally there. It was everything I had seen on television and it was in color and it was up close. Even the steel girders holding the upper deck excited me. And when we finally made our way to our seats, which were a classy green with fold-up bottoms, I was ecstatic. There, right in front of me, close enough to talk to, even touch, if I hadn't been so afraid of them, were the idols of my boyhood: Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, Jim Davenport, and Don Blasingame, and my favorite player, Orlando Cepeda.

I'll never forget my first thought: They look just like their baseball cards!

Oh, the sights and sounds that night: "Get your beer, here!" "Peeeeeeeea-nuts! Peeeeeea-nuts!" The roar when Willie Mays sent a ball over the left-field wall. The oooooh when Frank Robinson fanned.

It was a magic moment, one that I can never recapture, only recall.

Years later, when I married and had a son, my hope for him was that he grow up to love baseball. I named him Will...after my wife vetoed Orlando. Will was for two of the best players my team produced: Willie Mays and Willie McCovey. My wife thought it was for her grandfather and my grandfather. She's just finding out the truth in this book.

The winter Will was born I bought season tickets to the local Triple A club, the Louisville Redbirds, and took him to every home game his first summer. (He usually slept.)

Together, we watched the Cubs on television most afternoons and the Braves most evenings. (He preferred Thundercats cartoons.)

I signed him up for T-ball. (He hated it and spent most of his time in the outfield picking dandelions.)

For his eighth Christmas, I bought him a baseball-card album that included an assortment of cards. (He never even took the cellophane off.)

Then, came spring of his eighth year. One day after Harry Caray began bellowing "Take Me Out to the Ball Game," he went up to his room, dug out the album kit, and tore into it. Two hours later, he had all the cards neatly tucked into the polyurethane pockets. He needed more cards, he announced.

Now, he wanted to go to the Redbirds games, he wanted to get on a Little League team, he wanted to join a fantasy league. It was all happening almost too fast.

I knew what would be next: A big-league game.

I called the Reds box office. My first game had been in Cincinnati, albeit at Crosley Field; his first big-league game would be in Cincinnati, at Riverfront Stadium.

Baseball had a new fan.

Over the years, we went to games together, we operated a fantasy-league team together, we played catch in the backyard, and I pitched to him at the local field.

Then, something happened. He didn't want to go anywhere with me. He was embarrassed by my wardrobe, by my haircut, by pretty much everything about me. It's called the teen years. As he got over the embarrassment of having a father, he drifted into a new phase. Now, it wasn't that he didn't want to go to a ballgame with me, it was just that, well, Steve wanted him to play golf and Drew wanted him to bowl. And there were the calls from girls.

Now, something else has happened. His friends are all heading off to college but, because his school starts later, he's willing to hang out with his dad.

So, for the first time in five years, we are going to a big-league game together. To Cincinnati, of course. Scene of my first game, and his, too.

I just have to get us tickets.

In the beginning, it really was a game. There were no tickets; there was no need for tickets. It was just a gang of kids gathered in a field, playing a game. In some areas of this country they called it rounders, after the British game of the same name. Other places called it old cat or stool ball. It was a time in America when pilgrim wasn't just a name John Wayne called his rivals, and Indians weren't just from Cleveland. It was the eighteenth century.

Whatever this early game was, it certainly wasn't baseball. The only real similarity to the modern game was the bases. Kids would take turns running the bases while other kids tried to put them out by hitting them with a ball. It's always been fun to throw stuff at other kids.

(Incidentally, getting an out by hitting a player with the ball isn't as outlandish a rule as you might think. When I played backyard baseball in the fifties, there were days when we couldn't get up enough kids for a regular game. Sometimes, we'd play with as few as four guys. In the field, you had a pitcher and a shortstop. To get a player out, you'd hit him with the ball. And, yes, it did make you want to run faster.)

Over time, these eighteenth-century ball games evolved into what was once called base ball.

The first reference to a baseball-like game in America comes from a Christmas Day 1621 diary entry by Governor William Bradford of the Plymouth Plantation, who notes some of his subjects "frolicking in ye street, at play openly; some at Virginia pitching ye ball, some at stoole ball and shuch-like sport."

John Newbery's A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, an alphabet instruction booklet published in 1784, offers the first picture of American baseball, a woodcut showing boys playing "Base-Ball."

The ball once struck off away flies the boy

To the next destin'd post and then home with joy.

The bases of the title are posts stuck in the ground. There is no bat in the scene, but one boy appears ready to pitch underhand to a second boy standing, hand on post.

It was left to a group of young New Yorkers to synthesize all the disparate elements of rounders and cricket, town ball and stool ball, and formalize the rules of this new game. These professionals had been meeting regularly since 1842 on a field at 4th Avenue and 27th Street in Manhattan to get a little exercise playing this game of base ball. In 1845, one of their number, a twenty-five-year-old stationer named Alexander Cartwright, suggested they form a club. He even had a name for it, the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, a name derived from the Knickerbocker Engine Company, where Cartwright was a volunteer firefighter.

So, they made it official, this gentlemen's club, composed of seventeen merchants, twelve clerks, five brokers, four professional men, a bank teller, a "Segar Dealer," a hatter, a cooperage owner, and several "gentlemen." They elected Daniel L. "Doc" Adams, a physician, their president.

This was not, however, the first baseball club in New York. Baseball historians Thomas R. Heitz and John Thorn unearthed an interview Adams gave in 1896, in which he admitted to having played baseball in the city as early as 1839. "I began to play base ball just for exercise, with a number of other young medical men. Before that there had been a club called the New York Base Ball Club, but it had no very definite organization and did not last long. Some of the younger members of that club got together and formed the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club."

Adams said the players were all professional men "who were at liberty after three o'clock in the afternoon. They went into it just for exercise and enjoyment."

As president of the newly minted Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, Adams saw a need for a set of formal rules, so he put together a four-man committee that included himself and Cartwright, and sat down to write a set of by-laws. Only those four know who wrote what, but Cartwright, with his drafting skills, was called upon to draw the playing field and, as a result, his name has come to be attached to the rules, so much so that he is in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The rules they came up with would pass for baseball even today. No more outs by lethal throw. No more twenty-five men out in the field at one time. They created the diamond-shaped field, decreed three outs per turn and invented the foul ball.

Their document was published on September 23, 1845, as the "Rules and Regulations of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club." There were twenty rules, a sort of ten commandments times two.

Some had nothing to do with baseball, but with procedures for the club:

"1st. Members must strictly observe the time agreed upon for exercise, and be punctual in their attendance."

(Obviously, the club was having an attendance problem.)

"2nd. When assembled for exercise, the President, or in his absence, the Vice-President, shall appoint an Umpire, who shall keep the game in a book provided for that purpose, and note all violations of the By-Laws and Rules during the time of exercise.

"3rd. The presiding officer shall designate two members as Captains, who shall retire and make the match to be played, observing at the same time that the player's opposite to each other should be as nearly equal as possible, the choice of sides to be then tossed for, and the first in hand to be decided in like manner."

On the sandlot we tossed for sides, too: We tossed a bat. One captain caught it, each putting his fist above the other 'til one or the other could cover the knob with his thumb, thereby giving him first choose. That was how we made the sides "nearly equal," by picking back and forth.

By rule four, the Knickerbocker Club was onto something:

"4th. The bases shall be from 'home' to second base, forty-two paces; from first to third base, forty-two paces, equidistant."

Figuring three feet to a pace, that's 126 feet from home to second. The current rule book for Major League Baseball, in section 1.04 "The Playing Field," specifies, "When location of home base is determined, with a steel tape measure 127 feet, 3 3/8 inches in desired direction to establish second base." But, no one figured three feet to a pace in 1845: Heitz and Thorn found a contemporaneous dictionary that tabbed a pace at 2.5 feet, meaning the first fields were smaller, with base paths more in the range of 75 feet, closer to a Little League field. Those dimensions stand to reason, as the bats and balls were different too, making a smaller field necessary.

Rule 8 set a game at 21 aces, or runs -- first team to 21 wins. (We used to play that on the sandlot.) Some of the other rules hint at a move in the modern direction.

"10th. A ball knocked out of the field, or outside the range of the first and third base, is foul.

"11th. Three balls being struck at and missed and the last one caught, is a hand-out; if not caught is considered fair, and the striker bound to run.

"12th. If a ball be struck, or tipped, and caught, either flying or on the first bound, it is a hand-out.

"13th. A player running the bases shall be out, if the ball is in the hands of an adversary on the base, or the runner is touched with it before he makes his base; it being understood, however, that in no instance is a ball to be thrown at him.

"14th. A player running who shall prevent an adversary from catching or getting the ball before making his base, is a hand-out.

"15th. Three hands-out, all out.

"16th. Players must take their strike in regular turn."

Adams, Cartwright, and company took a children's game and gave it a design that enabled adults to play it.

You don't charge admission to a game until you need to and, at first, there was no need: Baseball was a social event. And, as noted in the first rules, a way to get a little exercise.

.  .  .

For better or for worse, the very setting down of a set of rules changed the game. Baseball was now -- and here's the ugly word -- It was no longer strictly a playground game.

Two weeks after publishing their rules, the Knickerbocker boys played the first recorded game under these guidelines, at their club ground, Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, a short...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0743233840

- ISBN 13 9780743233842

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages304

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0743233840-2-1

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0743233840-new

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0743233840

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0743233840

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0743233840

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0743233840

Why Is The Foul Pole Fair?: (Or, Answers to the Baseball Questions Your Dad Hoped You Wouldn't Ask)

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks158238

WHY IS THE FOUL POLE FAIR?: (OR,

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.7. Seller Inventory # Q-0743233840