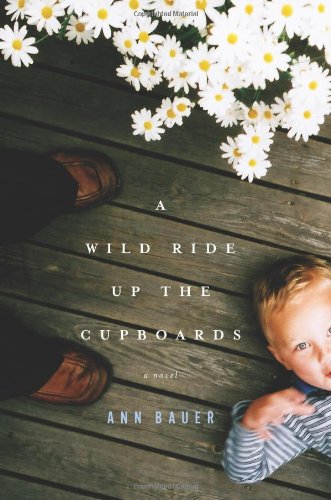

Items related to A Wild Ride Up the Cupboards: A Novel

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

During the winter of Edward's first-grade year, I would often dream that he was dead. These were long,complicated nightmares from which I would awaken -- gasping,wild with grief, my heart pounding -- into total darkness.

It was early January,a night so cold I had piled four blankets on the bed before getting in just hours before. I opened my eyes and lay still for a long time,letting my dream fade and listening to the ticking of snow crystals against the windowpane.Gradually,the rapid drumbeat in my chest died down. My eyes focused and shapes emerged: fuzzy gray outlines against black air.For weeks I had awakened every morning around three-thirty, but I had never once succeeded in falling back to sleep.

Jack turned and sighed, a gust of warm air against my neck. My husband could sleep through anything, including my thrashing and the stiff terror that followed.Edward could sleep through nothing,not even perfect silence.Now,I could feel him in the next room, alert and anxious, twitchy, concentrating hard on trying not to move. I imagined his thoughts streaming through the wall between us, spangling like stars.

A ghost of vapor hung over the radiator and the window above us was covered with rime. For a moment I burrowed backward into Jack, who radiated heat like a furnace. Still sleeping, he slipped his arms around me and I stayed inside them,contented,for a few minutes. But when my back began to perspire against his bare chest, I knew it was time to get up.

My body was so large at this point,my stomach so distended,I had to set myselfup in order to vault out of bed. I twisted to the side ofthe mattress and flattened a palm squarely against Jack's top shoulder, then shoved hard against his immovable bulk and made it over the edge on the first try. I stood,panting,and reached out to the wall to steady myself.

The wooden floor was hard and cold and my feet immediately started to ache.I needed socks,which presented a problem.Finding the socks wasn't difficult.We'd given the larger bedroom,the "master,"to the boys, and set up a nursery in the smaller bedroom across the hall. Jack and I slept in an alcove meant for storage,or a tiny office.It was L-shaped,roughly the size of a Ping-Pong table with a little air pocket attached to the top.I could stretch out one arm and retrieve a pair of socks from the dresser. But putting them on was a different story.

During the day, Jack helped dress me: I would stand in line along with the boys as he moved from one of us to the next, folding white socks neatly over our ankles and tying bows on our shoes. Rather than wake him now,which he had told me to do,I decided to apply the socks myself. I took a deep breath and held it, bending over and reaching for one foot,terrified that I was squeezing the baby to death. After slipping the first one on,I rested for a few seconds before repeating the maneuver on the other side.

I knew I should let Edward alone but it was as if there were an invisible cord strung between us,pulling me toward him.I shuffled softly down the carpeted hall and pushed open the door. Jack had hung special room-darkening shades in the boys'room so the blackness was even thicker than in ours.Stepping inside was like moving through cloth and it took a full minute for me to see the outline of Matt sleeping under his covers, his breath sounds smoothly puttering, his humped-up body a miniature version of his father's.

Edward didn't raise his head from the pillow but the air was full of him, tight and crackling with his energy. Every night he waged the same battle with sleep: mind racing,eyes blinking.For twelve straight nights now he'd lost.

"Sweetheart, try to relax."I knew this was pointless but found myself saying it every time I stared down at him.What I wanted was to walk over and smooth back his hair,or lie down on the bed and pull him in, cradling him as I did when he was a baby,when he would relax against me and let his eyelids sag until he fell asleep. But now his pale eyes were wrinkled and wary and I was afraid if I touched him he'd flinch and retract, like those tiny worms that coil into tight springs when you poke them with your finger.

"Close your eyes and think about Lake Superior." I tried to make my voice rhythmic, hypnotic." Think about the way the waves keep moving against the rocks. Pretend you're walking on the water." My voice trailed off as I left, closing the door behind me, wondering how many nights a child can go without sleep before he dies. The hallway seemed to swell and contract like a bellows and my throat filled with a metallic taste. I closed my own gritty eyes, leaned against the wall,and swallowed several times in order not to be sick.

Downstairs, I flipped on an overhead light, filled the teakettle,and lit a burner underneath. The kitchen was a bright place,far less ominous than the cold bedrooms upstairs. Gas hissed out and the stove flame burned red, then a clean, hot orange tipped with yellow and blue. I opened the cupboard where Jack had hidden a bag ofespresso beans in a tin canister behind the blender we never used. He drank coffee only when he had to, when he was changing shifts and needed to stay awake all night. And he tried to do it when I wasn't around, so I wouldn't have to suffer. But I was not so kind to myself.

Every morning before he got up I took the canister down, opened it, and breathed in its scent. I craved coffee in a desperate, passionate way, like heroin or cocaine. I fantasized about how my hand would curve around the warm cup, how the steam would dampen my face. I wondered ifthis was the sort ofdesire that made junkies sell their children for a fix. Jack insisted real drug withdrawal was much worse; secretly, I doubted it. Sometimes I imagined I was having full-scale hallucinations: bugs crawling on my eyelids or purple snakes slithering across the floor. But I never drank any.I knew the consequences of doing the wrong things during pregnancy,even if I wasn't sure exactly what all those wrong things were. I was determined never to do them again.

The window over the kitchen sink was black. With the light on inside,the houses behind ours weren't visible. Nor was the clothesline in our yard,where a red towel that had hung through three blizzards was now completely frozen with one stiff corner pointing down toward the ground. The world was noiseless at four o'clock in the middle of winter and my movements -- putting the kettle on the stove,setting a cup down on the countertop,shutting the cupboard door after getting a tea bag -- seemed to pop rudely in midair.

This was the eighth month of my third, and easiest, pregnancy. Even so,every change had taken me by surprise. I'd forgotten all about the inhuman bulkiness of this stage, the shortness of breath, the leg cramps. And the certainty that the downward pressure inside my body had grown so intense, the baby must be about to drop right out onto the floor. I had imagined this far too often: the infant in my mind falling headfirst and bouncing several times, its skull breaking open like an eggshell before the small body skittered to a stop.

Just yesterday,the doctor had assured me it was pinched nerve endings and not fetal distress that was causing the currents of pain to run down my legs. Of course,he was a neurologist, not an obstetrician,and I had met him only that afternoon. But I liked Barry Newberg more than my own OB; he seemed smarter and his conclusions made sense to me. The fact that I believed in him was one of the things keeping me up tonight. The previous afternoon Newberg had also offered a possible diagnosis for Edward, one worse than anything I'd ever heard before or been able to dream up on my own.

I sat at the kitchen table,using one hand to balance a mug of tea on the shelf of my stomach. The tabletop was clear but for a cellophane-wrapped library book and a thick sheaf of cream-colored pages held together with a large industrial staple.For a moment,my hand hovered above the book but I pulled it away and lurched up out of my chair to look for a pen instead. I found one in the desk we'd tucked into a corner of the living room: blue with a fine, wet tip,the sort I used to edit galleys at the newspaper. I took this and an afghan,which I wrapped awkwardly around myself, and returned to the table.

The questionnaire began, as these things usually do, with easy questions. Name, address, parents' names and marital status. Born: March 12, 1988. Age: 6.Grade in school:1st. Siblings: one, Matthew, 4 years old. Then I turned the page. Developmental Milestones, it said. When did he first smile? That was easy. I remembered the day, how amazed we were,Jack and I,that this three-week-old baby could look so wise and amused by two ridiculously young, awkward parents. But then the questions got harder. When did he roll over? Sit? Stand assisted? Stand unassisted? Eat with a fork?

A better mother would have all these things recorded in a baby book along with locks of hair and inky footprints. I had only flashes of memory: Edward sitting on the living room floor surrounded by pillows in case he toppled over, while Jack's friend Paul sat behind him on the couch and played a guitar. Jack extending one long finger for Edward to use for balance as they waded through a creek near our apartment. Was Edward eleven months old? Thirteen?

When Edward was an infant,I had showed his pediatrician the dark spots on his back and side during a well-baby checkup. After he withdrew, years later,I'd returned to ask if there could be any connection. "Mothers," she'd said, shaking her head, as if I were so silly to be worried about a little boy who'd suddenly stopped singing and begun chewing his clothes. That was back when she insisted mutism was just a phase he would grow out of. About six months later, she changed camps completely and decided he'd probably suffered some sort of brain damage. How,she wouldn't say.

Recently,we had been referred to Barry Newberg. Very expensive, well educated,and new in town, he'd already discovered that one supposedly autistic child actually was suffering from a yeast allergy and cure...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0743269497

- ISBN 13 9780743269490

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Wild Ride Up the Cupboards: A Novel

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks152201