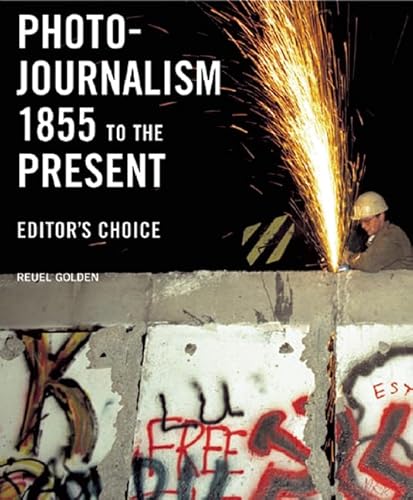

Items related to Photojournalism 1855 To The Present: Editor's Choice

In these commentaries and in his informative introduction, Golden discusses the particular challenges of photojournalism, such as the relationship between photographer and subject, and the moral ramifications of aestheticizing human suffering. Yet perhaps most importantly, his text also encourages the reader to look closer and discover how well the photographs speak for themselves. From Frank HurleyG«÷s groundbreaking World War I battlefield shots to Mary Ellen MarkG«÷s stark portraits of American poverty and James NachtweyG«÷s haunting pictures of the September 11 attacks, the images in this book prove that even in our era of twenty-four-hour video-on demand, the still photograph remains as powerful as ever.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The war in Iraq and its aftermath were relentlessly covered by thousands of television channels from all over the world. Journalists filed reports from burnt-out rooftops, from inside American tanks making their way toward Baghdad, from refugee camps. It was a big story, as war always is, and the 24-hour news channels were anxious not to miss anything yet invariably they did. From all the hours, days and weeks of moving footage, there is nothing that really lingers in the memory from this strange time. The television coverage was immediate, dramatic and never-ending. It showed us a lot, but taught us very little. It is the still photographs of the conflict that are memorable. The famous image of a statue of Saddam Hussein being toppled over by a jubilant crowd was a powerful symbol of repression and subsequent liberation. On the flip side of that, there were the chilling images taken by an anonymous American soldier with a cheap digital camera of Iraqi prisoners being abused by their US captors in the hellhole of Abu Ghraib. When historians look back at this period and try to make sense of what happened, it is these images, as well as photographs taken by people such as Luc Delahaye, Tom Stoddart, Jerry Lampen, James Nachtwey, and dozens of others, that will be used as evidence.

Photojournalism’s perspective

These photojournalists and all the others featured in this book were the key witnesses to a series of events that together make up recent history. They are our eyes on the world. Great photojournalism witnesses events that we wouldn’t necessarily see or be allowed to see, or even want to think about. At its most basic definition, photojournalism is the presentation of stories through photographs photojournalists are journalists with cameras. Since the inception of the medium, when Roger Fenton photographed the Crimean War in the mid-nineteenth century, photojournalists have been preoccupied with photographing humanity at the extreme edge of existence. War, civil unrest, famine, disease, natural disasters, poverty, homelessness: these are the grim stories told by photojournalists for more than 150 years.

Some critics resent this narrow, bleak viewpoint and continually question why photojournalists focus only on the negative. These are valid criticisms, but they can be rebutted. First, photojournalists are working in a commercial environment where there has always been a demand for this kind of image and story. Sadly, good news has never helped sell newspapers. Second, photographing a harrowing or dangerous event presents the photojournalist with a series of logistical, aesthetic and moral challenges. By challenging themselves, they in turn challenge the viewer on an emotional and intellectual level. The best photojournalism gets us to see and feel what is happening and more importantly forces us to ask Why?”.

The logistical challenge is to get the photograph in the first place; the aesthetic challenge is to make the image as compelling as possible. Often this means beautifying the misery and suffering, and the more enlightened photojournalists are conscious of this dilemma. Yet they also realize that a well-composed, attractively toned and perfectly lit print is the most effective way of connecting and engaging an often indifferent audience.

The moral challenge facing photojournalists is the notion of conveying an objective truth. As bystanders, they are supposed to merely record events and not influence them in any way. In this book there are controversial examples where the photographer supposedly set up” the shot the more extreme cases of a photojournalist tampering with the truth. Yet the notion of objectivity is ambiguous, and every time the photojournalist takes a photograph subjective judgements are being made, starting with the fundamental decision about what to photograph and equally importantly what to leave alone. Many factors will influence how the image is perceived and interpreted: how the image is composed and cropped; whether it is shot in color or black-and-white; the detail that is included; whether the photograph is shot in close-up or the camera is pulled back; the accompanying caption. This doesn’t mean that the photographer is not telling the truth; it is just one version of the truth. Click the shutter again and the viewer is confronted with a new version.

The evolution of the genre

There were some remarkable photojournalists in the nineteenth century: the pioneering Roger Fenton, the enigmatic Felice Beato, and Alexander Gardner, who photographed the American Civil War. (He, rather than the more famous Matthew Brady, makes it into this book, since there has always been some controversy over Brady, who claimed sole copyright from all the photographers who worked under him.) Yet overall two factors hindered the development of the medium. Firstly, cameras were extremely bulky and unwieldy contraptions involving glass plates and long exposure times, fine for formal portraiture, but not suited to the spontaneous nature of photojournalism. Secondly, there was no demand for journalistic images, apart from private collectors and museums.

This was to change in the first 20 years of the twentieth century. In 1910 the rotary printing cylinder was invented, which meant that text could now be combined with photographs. Following on from that was the development of the small hand-held camera, the Leica, which was to change the genre forever. Armed with a Leica, a photojournalist could get close to the action, taking photographs in quick succession, as the camera followed the movements of the human eye. These twin developments propelled photojournalism into people’s consciousness and homes with a spate of photo-led publications.

This golden age of photojournalism,” as it became known, was roughly to last from the mid-1930s, when Life was selling by the millions and even by today’s standards photographers were being paid a lot of money to shoot stories, $20,000 in the case of the legendary Robert Capa. Life magazine loyally served its readers with its use of extended photo essays, where the photographer was given sufficient space to develop a coherent narrative over page after page.

Photojournalism was perceived as glamorous and the photographers, led by those such as Capa and Cartier-Bresson, had a high self-regard. What they lacked, however, was power. This was to change with the formation of the Magnum photo cooperative in the late 1940s. Magnum established the principle that the copyright of the photograph belonged to the creator. Since one of its founders was Cartier-Bresson, Magnum also played a significant role in elevating the genre from a craft into an art form, and in time photojournalism would be displayed in galleries and reproduced in glossy books. Magnum also created an infrastructure that allowed its members to spend a long time on stories, to reflect, rather than just react to news.

The Second World War shaped the careers of a generation of legendary photographers, such as Robert Capa and W. Eugene Smith. Similarly, the Vietnam War around 20 years later established a new kind of photojournalism, which produced its own legends photographers such as Larry Burrows, Don McCullin, Gilles Caron and Philip Jones Griffiths. These (sometimes color) images were brutal in their depiction of war. They were graphic and technically very sharp, since the quality of film and cameras had improved significantly. While Capa saw war in heroic terms, these men clearly identified with the victims of war, rather than with the occupying force. They wanted their photographs to bring about change and to a large extent they succeeded.

Their sensibility, dedication and moral responsibility was adopted by the third generation of war photographers who covered the conflicts in the Middle East in the 1970s and 19080s and in particular the civil war in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Photographers such as Gilles Peress, Luc Delahaye, Roger Hutchings, James Nachtwey, Tom Stoddart, Carol Guzy, Eli Reed and many others were committed, brave and passionate, but less idealistic than their 1960s counterparts. Skeptical and at times distrustful of both their role and the media in general, these photographers also now had digital technology at their fingertips, which revolutionized the taking and transmission of photographs. Images could be taken in a war zone, transmitted down the wire in a matter of just a few seconds and, make it on tot he front pages of a newspaper within minutes.

The witnesses

Most of the photographs featured in this book are traditional photojournalists who report from the front-line. Their images of major world events were, and are, seen on the front pages of newspapers. The selection process for a book of this nature is never easy, and inevitably great photographers are going to be omitted. There is not one criterion that justified selection but rather a combination of many factors: technique, originality, consistency, versatility, dedication to the point of obsession to a particular story, political awareness. Above all else, however, everyone in this book has produced memorable and compelling photographs the move us in some way.

There are also photographers here like Martin Parr, Zed Nelson, Sebastiao Salgado, W. Eugene Smith and Lewis Hine who are as remarkable as any photojournalist, even though their work falls within the genre of social documentary. This is photography that moves away from the purely dramatic news event and focuses on how we live and interact with each other. These photographers are included in the book because almost all of them started out as hard news” photographers who then evolved into a different type of storyteller. Boundaries are never clear-cut, and history is not just the unfolding of dramatic events. Social, economic and cultural issues like gun control, migration and tourism are also part of what form, in the words of Henrich Cartier-Bresson, the decisive moments” of history.

The future of photojournalism

People have been writing about the death of photojournalism since the invention of television. Fifty years on, in our celebrity-obsessed world, there might appear to be little room for serious stories and photographs. But even in the golden age” of Life magazine, most of its covers featured film stars and even W. Eugene Smith’s seminal essay on the country doctor wasn’t a cover story. As long as there are newspapers, current affairs magazine and web sites, there will always be a space for serious news photographs.

There are genuine concerns that the ease with which a photograph can be digitally manipulated means that the camera can indeed lie. Yet photographers have always had the ability to manipulate an image, either by setting a shot up or making alterations in the darkroom. True, clicking a mouse in Photoshop is a lot easier than spending hours changing a print in the darkroom, but this has made both viewers and the newspapers themselves much more alert to the possibility of anything underhand going on. During the last war in Iraq, the LA Times sacked one of its more distinguished photographers for digitally altering the perspective of an image.

Everyone these days has a digital camera or an image-taking device on his or her cell phone. As a result, whatever is going on in the world, there will be someone present who will be able to record it and then sell his or her images to a newspaper or web site. The barriers are therefore being broken down between the committed photojournalist and the amateur snap shooter. There are billions of photographs pinging around in cyberspace and there is a danger of image overload, where we are jaded and feel that we have seen everything there is to see.

Will photojournalism still have an important function in the years to come? The war in Iraq gave us a glimpse into a future where serious photojournalism will simply work in tandem with the amateur opportunist, like the aforementioned American soldier who took those deeply disturbing photographs from the Abu Ghraib prison. If the twenty-first century is as bloody and violent as the century that preceded it, then photojournalism will still have a role to play as an observer and a witness. That is both the good and bad news.

Reuel Golden

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAbbeville Press

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0789208954

- ISBN 13 9780789208958

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- EditorGolden Reuel

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Photojournalism 1855 To The Present: Editor's Choice

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0789208954

Photojournalism 1855 To The Present: Editor's Choice

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0789208954

Photojournalism 1855 To The Present: Editor's Choice

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0789208954

Photojournalism 1855 To The Present: Editor's Choice

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0789208954

Photojournalism 1855 To The Present: Editor's Choice

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks228120

PHOTOJOURNALISM 1855 TO THE PRES

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 3.45. Seller Inventory # Q-0789208954