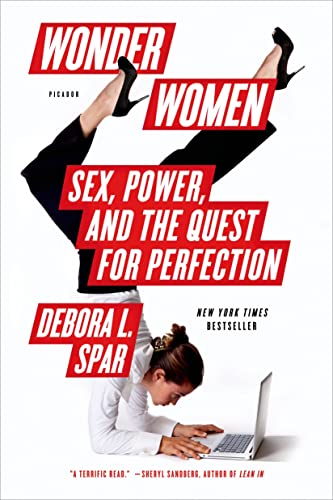

Items related to Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Debora L. Spar spent most of her life avoiding feminism. Raised after the tumult of the 1960s, she presumed that the gender war was over. "We thought we could glide into the new era with babies, board seats, and husbands in tow," she writes. "We were wrong."

Spar should know. One of the first women professors at Harvard Business School, she went on to have three children and became the chair of her department. Now, she's the president of Barnard College, arguably the most important women's college in the country, and an institution firmly committed to feminism. Wonder Women is Spar's story, but it is also the culture's. Armed with reams of new research, she examines how women's lives have, and have not, changed over the past fifty years-and how it is that the struggle for power has become a quest for perfection. Wise, often funny, and always human, Wonder Women asks: How far have women really come? And what will it take to get true equality for good?

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Growing Up Charlie

When I was growing up in the early 1970s, there was a commercial for Charlie perfume that appeared on all the network stations. I remember it vividly, as do many women of my generation. It showed a beautiful blond woman prancing elegantly down an urban street. She had long bouncy hair, a formfitting blue suit, and a perfect pair of stiletto heels. From one hand dangled a briefcase; from the other, a small, equally beautiful child, who gazed adoringly at her mom as they skipped along. The commercial never made clear, of course, just where Mama was going to leave her child on the way to work, or how they both managed to look so good that early in the morning. Instead it simply crooned seductively, in the way of most ads, promising something that was “kinda fresh, kinda now. Kinda new, kinda wow.”

The perfume, if I recall correctly, was not particularly nice. But the commercial was terrific.1

So was another of the same vintage for Enjoli, a similarly unremarkable fragrance. This one’s heroine was even bolder, strutting home in a tight skirt after an apparently successful day and proceeding directly to the kitchen. As she cheerfully whipped up some kind of dinner delight, she sang a provocative little anthem, which most women of my age, I’ve discovered, still recall. “I can bring home the bacon,” she cooed. “Fry it up in a pan. And never let you forget you’re a man. ’Cause I’m a woman. Enjoli.” Never mind the perfume. The lifestyle was enchanting.

Both of these commercials aired in the early 1970s, right at the edge of Watergate and the free love of Woodstock. They aired only briefly, selling products that slipped eventually from the public eye. But they stuck somehow in the public consciousness, or at least in the minds of schoolgirls like me, who simply presumed that life in the grown-up world would be just like the ad for Charlie. We’d have careers to skip to, kids to adore us, and men waiting to douse us with perfume the moment we waltzed through the door. Money and great shoes only sweetened the package.

This wasn’t, of course, the life that our mothers were living. In 1970, only 43 percent of women worked outside the home.2 In upper-middle-class white families like my own, the number was slightly higher, hovering by 1974 at around 46 percent.3 Most of these women worked in “traditional” fields such as teaching or nursing, and they rarely wore stilettos to the job. Yet somehow, girls growing up in that era believed—thought, presumed, knew—that they would be different. That instead of replicating their mothers’ suburban idylls of parent-teacher conferences and three-tiered Jell-O molds, they—we—would go the way of Charlie, enjoying children and jobs, our husbands’ money and our own. And through it all, we would be smiling and singing, gracefully enjoying the combined pleasures of life. In 1968, 62 percent of young women had expected to become housewives by the time they were thirty-five. By 1979, just eleven short years later, that percentage had plummeted to 20.4 The rest of us presumed that we’d leave the world of housewifing far, far behind.5 In 1979, fully 43 percent of American girls predicted that they would hold professional positions by the time they were thirty-five.6

Where did we possibly get such ideas?

I offer three suspects: our mothers, the media, and the feminists.

Let’s start with the mothers, since they are always the easiest to attack. Women born between 1960 and 1975 have mothers who were born generally between 1935 and 1950 and came of age, generally again, between the late 1940s and early 1960s.7 This was a period, in retrospect, of unprecedented prosperity and stability in the United States. Real incomes were growing steadily, and millions of Americans decamped for the suburban towns cropping up across the country. Freed from the rigors of economic depression and war, women of this generation rarely worked outside the home unless it was absolutely necessary. As late as 1955, for example, only 28.5 percent of married American women had paying jobs.8 The remainder basked in the comforts that their generation could now afford and raised their own daughters—my generation’s mothers—to strive for the Good Housekeeping version of the American dream: a house, a husband, 2.5 children, and a yard. Or as the poor shopgirl, Audrey, fantasizes in the musical Little Shop of Horrors, “A washer and a dryer. And an ironing machine. In the tract house that we share. Somewhere that’s green.” She ain’t exactly Charlie.9

But when these girls of the 1940s and 1950s grew up to be mothers, they wanted their daughters to have something else. Something more than the washer and the dryer and the ironing machine.10 They wanted them, in short, to have careers, and to participate more actively in the social progress that was starting to seep through the seams of American life. So the good girls of the Eisenhower era became the pushy mothers of the Nixon era, dragging their offspring to pottery classes and poetry readings, convincing them that girls really could do whatever they wanted.

My own mother was adamant on this point. After marrying at twenty and having me at twenty-two, she was fully convinced that girls of my generation would face a fundamentally different set of options—even though she had grown up in very comfortable circumstances, graduated from college, and returned to teaching kindergarten when I turned ten. “I never had the opportunities that you do,” she would say. “I would have loved to go to law school, but there was no way my parents would ever have let me go.” And statistically, she was right. In 1961, when she graduated from Hunter College, only 3 percent of law students in the United States were women. When I graduated from college twenty-three years later, that number had risen to 37 percent. The same thing happened in medical schools, where the percentage of female students rose from 5 to 28 percent over this period, and in business schools, where it rose from 3 to 30 percent.11 So the women of my generation did indeed have all kinds of opportunities stretching beyond the green lawns of suburbia. And our mothers were chanting from the sidelines, urging us to grab them all.

Meanwhile, of course, the media were driving this fairly radical change as well, luxuriating in and promoting a new brand of American dreaminess. When I started watching television in the late 1960s, the choices were few, far between, and unabashedly wholesome: Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, and my all-time favorite, The Brady Bunch. While these shows were socially more progressive than the older Leave It to Beaver fare that I caught on rare days home from school, they still portrayed a feminine ideal centered largely on the happy suburban mom. The leading women were typically full-time mothers, devoted to their school-age children and their affable if bumbling husbands. They were pretty in a well-coiffed and sensible way, and invariably cheerful. When Carol Brady and her three daughters go on a camping trip with her new husband and his three sons, for instance, Mrs. Brady smilingly prods her grumpy girls into action. “We have three new brothers and a new father,” she reminds them, “and if they like camping, we like camping!”12 Similarly, when the young witch Samantha hears from her husband the rules of suburban wifedom—“You’ll have to learn to cook, and keep house, and go to my mother’s house for dinner every Friday night”—she is eagerly compliant. “Darling,” she gushes, “it sounds wonderful!”13

Within only four or five years, however, new figures started slipping across the TV screen, very different kinds of women who hinted provocatively at a whole new sort of post-Brady experience.14 Maude debuted in 1972, portraying an outspoken and strong-willed woman who married four different men (one died; she divorced two), ran for Congress, and decided, when she became pregnant at forty-seven, to have television’s first abortion. She was followed by Rhoda (1974), a boisterous single woman who manages to date, marry, divorce, and start her own window dressing business all in the show’s 110 episodes. Then came Alice (1976), a single working-class mom. 1976 also famously saw the launch of Charlie’s Angels, in which gorgeous, scantily clad women pull firearms from their bikini tops to rid the world of evil. Not surprisingly, the Charlie commercial that captured my imagination debuted around this same time (1974), as did the Enjoli ad. In fact, Shelley Hack, the beautiful woman from the Charlie ad (referred to, of course, as “the Charlie girl”) actually became one of Charlie’s angels in 1979. It was a good time for Charlie.

Even more dramatic changes were underway in the world of print media. Up until this point, women’s magazines had been a staid and comforting lot, led by long-standing publications such as Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping. These were, to be sure, fairly serious magazines. They provided a rare outlet for female authors and dealt, at least in passing, with topics like divorce, infertility, and contraception. Their daily fodder, however, was simpler fare, consisting largely of advice on how to clean a perfect kitchen, make a perfect pot roast, or deal with a toddler’s sore throat: THE DINING ROOM IS LIKE AN INDOOR GARDEN announced one 1960 headline from Ladies’ Home Journal. FUN WITH YARNS! promised another. And then Helen Gurley Brown and Gloria Steinem smashed onto the stage, refurbishing Cosmo (in 1966), launching Ms. (in 1972), and turning the world of women’s magazines completely upside down. Because now, instead of reading about pot roast and runny noses, women could read about sexual prowess and adultery.15 They could learn about homosexuality (LESBIAN LOVE AND SEXUALITY), masturbation (GETTING TO KNOW ME: A PRIMER ON MASTURBATION), and more sex (THE LIBERATED ORGASM).16 Suddenly, playing with yarn didn’t sound like much fun.

By the time we girls of the 1970s entered high school, therefore, the world began to echo—even shout—the words our mothers had been telling us for years. In no uncertain terms, women of my generation were being told, for the first time in history, really, that girls were just as good and as capable as boys, and that women could be, should be, whatever they wanted to be.

And what lay behind this sudden bout of boosterism? Precisely the same thing that had catapulted Helen Gurley Brown and Gloria Steinem to power, the thing that had tossed Carol Brady off the screen and replaced her with Charlie’s angels. It was the feminist revolution, hatched in the late 1960s and apparently now here to stay.

To be sure, feminism itself was hardly a new phenomenon. Indeed, as Estelle B. Freedman describes in No Turning Back, a history of feminism, the global movement for women’s rights had a long and complicated past, including the liberal struggle for women’s suffrage launched in the mid-nineteenth century, socialist-inspired campaigns to protect working girls and women in the early twentieth century, and the decades-long battle, led by crusaders such as Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman, to provide women with access to contraception.17 But the feminism of the 1960s was distinct. This was a feminism that promoted not the political rights of women, or the legal status of women, but rather the very identity of women. It was a feminism that tore at the very roots of an American ideal and prescribed a whole new model in its place. As presented (and distorted) by the mainstream media, it was a feminism that was greedy to its core, proclaiming that women could have money and children and sex and power, along with fabulous shoes. Like men, in other words, women could have it all. And boy, did I want it.

The Feminine Mystique

Unlike most social phenomena, the feminism that surrounded women of my generation can largely be traced to a single event—a book, in this case, that revolutionized how society saw women and, more important, how they saw and imagined themselves.

In 1963, Betty Friedan, a seemingly ordinary housewife with a husband and three children, published The Feminine Mystique, a searing investigation of what she termed “the problem that has no name.”18 According to Friedan, millions of women living in the postwar American idyll were suffering from a dissatisfaction that was both pervasive and profound. Although they had children and husbands they claimed to adore, young mothers reported feeling empty or unsatisfied, searching for a sense of fulfillment that didn’t come from being “a server of food and a putter-on of pants.”19 Women, Friedan insisted, wanted more. They wanted lives of their own, and careers of their own, and ideas that belonged to them. But rather than pursuing their dreams, women across postwar America were routinely entrapped by the “feminine mystique,” convinced that ecstasy came in a cleaning powder and fulfillment lay in serving others.

In shaping her complaint, Friedan drew heavily on the feminists who had preceded her. Her focus on power and economic conditions, for example, echoed the critiques of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex; her demand for women’s emancipation followed a line of argumentation that stretched back to Marx and Engels.20 But something was different about this book. It wasn’t making an academic argument, or an abstract one. It wasn’t about principles or even politics. Rather, it was written—or at least appeared to be written—by a housewife, for a housewife. It was the literary equivalent of a kaffeeklatsch, something that women could share, quietly and among themselves, in the privacy of their kitchens. Or, as Anna Quindlen recalls in the introduction to the 2001 reissue of the book: “My mother had become so engrossed that she found herself reading in the place usually reserved for cooking.”21

What was it that Friedan managed to capture? It wasn’t really politics, since the political battles of feminism had been raging long before Friedan took up the cause. Indeed, fights over the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), mandating legal equality for men and women, had been under way for decades.22 Her book wasn’t about economic power, really, or about giving women access to things like birth control or college degrees that had motivated feminists of the past. Instead, she was railing about what could easily have been dismissed as social subtleties—daily routines faced by millions of middle-class moms and the forces that had consigned them to this fate. Or, as Friedan writes in the book’s opening passage: “It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’”23

It’s easy to imagine how such a question might well have gone unanswered. Friedan was an unknown author at the time of her book’s publication, after all, and the previous two decades had already witnessed a slow but steady retreat from earlier feminist agendas. In 1947, for example, two prominent psychologists published Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, a bestselling treatise that described feminism as a “deep illness” and warned that any woman who fell prey to its temptations was “neurotically disturbed” and likely afflicted with a nasty case of penis envy.24 And in 1955, even Adlai Stevenson, a leading politician esteemed for his liberal leanings and she...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPicador

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1250056063

- ISBN 13 9781250056061

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 1250056063-11-31738887

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 1250056063-2-1

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-1250056063-new

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 3330186

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1250056063

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1250056063

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1250056063

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1250056063

Wonder Women: Sex, Power, and the Quest for Perfection

Book Description Condition: new. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. Seller Inventory # PSN1250056063