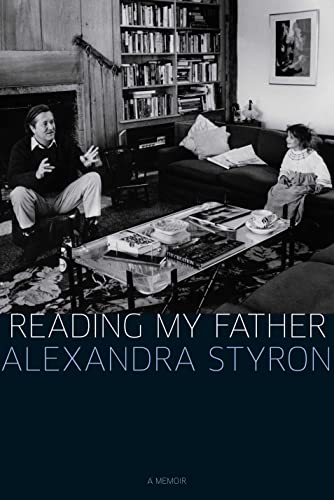

Items related to Reading My Father: A Memoir

In Reading My Father, William Styron’s youngest child explores the life of a fascinating and difficult man whose own memoir, Darkness Visible, so searingly chronicled his battle with major depression. Alexandra Styron’s parents—the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Sophie’s Choice and his political activist wife, Rose—were, for half a century, leading players on the world’s cultural stage. Alexandra was raised under both the halo of her father’s brilliance and the long shadow of his troubled mind.

A drinker, a carouser, and above all “a high priest at the altar of fiction,” Styron helped define the concept of The Big Male Writer that gave so much of twentieth-century American fiction a muscular, glamorous aura. In constant pursuit of The Great Novel, he and his work were the dominant force in his family’s life, his turbulent moods the weather in their ecosystem.

From Styron’s Tidewater, Virginia, youth and precocious literary debut to the triumphs of his best-known books and on through his spiral into depression, Reading My Father portrays the epic sweep of an American artist’s life, offering a ringside seat on a great literary generation’s friendships and their dramas. It is also a tale of filial love, beautifully written, with humor, compassion, and grace.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

WE BURIED MY father on a remarkably mild morning in November 2006. From our family’s house on Martha’s Vineyard to the small graveyard is less than a quarter mile, so we walked along the road, where, it being off-season, not a single car disturbed our quiet formation. Beneath the shade of a tall pin oak, we gathered around the grave site. Joining us were a dozen or so of my parents’ closest friends. The ceremony had been planned the way we thought he’d have liked it—short on pomp, and shorter still on religion. A couple of people spoke; my father’s friend Peter Matthiessen, a Zen priest, performed a simple blessing; and, as a family, we read the Emily Dickinson poem that my father had quoted at the end of his novel Sophie’s Choice.

Ample make this bed.

Make this bed with awe;

In it wait till judgment break

Excellent and fair.

Be its mattress straight,

Be its pillow round;

Let no sunrise’ yellow noise

Interrupt this ground.

My father had been a Marine, so the local VA offered us a full military funeral. Mindful of his sensibilities, we declined the chaplain. We also nixed the three-volley salute. But we were sure Daddy would have been pleased by the six local honor guards who folded the flag for my mother, and the lone bugler who played taps before we dispersed. Of military service, my father once wrote, “It was an experience I would not care to miss, if only because of the way it tested my endurance and my capacity for sheer misery, physical and of the spirit.” The bugler, then, had honored another of my father’s quirks: his penchant for a good metaphor.

A year and a half later, I was walking across the West Campus Quad of Duke University, my father’s alma mater. Passing beneath the chapel’s Gothic spire, I opened the heavy doors of Perkins Library and headed for the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library. It is there that the William Styron Papers, 22,500 items pertaining to his life and work, are housed. I was at the end of my third trip to North Carolina in as many months. Before I flew home to New York that afternoon, there were two big boxes I still hoped to get a look through.

In 1952, when he was twenty-six, my father published his first novel, Lie Down in Darkness. The book was an immediate success, and he was soon hailed as one of the great literary voices of his generation. Descendants of the so-called Lost Generation, my father and his crowd, including Norman Mailer, James Jones, and Irwin Shaw, embraced their roles as Big Male Writers. For years they perpetuated, without apology, the cliché of the gifted, hard-drinking, bellicose writer that gave so much of twentieth-century literature a muscular, glamorous aura. In 1967, after the disappointing reception of his second novel, Set This House on Fire, my father published The Confessions of Nat Turner. It became a number one bestseller, helped fuel the tense national debate over race, and provoked another one regarding the boundaries of artistic license. Sophie’s Choice, published in 1979, won him critical and popular success around the world. Three years later, with the release of the film adaptation starring Meryl Streep and Kevin Kline, that story also brought him an extraliterary measure of fame. Winner of the Prix de Rome, American Book Award, Pulitzer Prize, the Howells Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and France’s Légion d’Honneur, my father was considered one of the finest novelists of his time. He was also praised, perhaps by an even larger readership, for Darkness Visible, his frank account of battling, in 1985, with major clinical depression. A tale of descent and recovery, the book brought tremendous hope to fellow sufferers and their families. His eloquent prose dissuaded legions of would-be suicides and gave him an unlikely second act as the public face of unipolar depression.

As it turned out, the illness wasn’t finished with my father. I think we all recognized, in the aftermath of his cataclysmic breakdown, that Bill Styron had always been depressed. A serious drinker, he relied on alcohol not only to self-medicate but to charm the considerable powers of his creative muse. When, at sixty, liquor began to disagree with him, he was surprised to find himself thoroughly unmanned. For many years after his ’85 episode, he maintained a fragile equilibrium. But the scars were deep, and left him profoundly changed. He was stalked by feelings of guilt and shame. Several setbacks, mini major depressions, humbled him further and wore a still deeper cavity in the underpinnings of his confidence. It seems that my father’s Get out of Jail Free card had been unceremoniously revoked. And though he went about his business, he’d become a man both hunted and haunted.

* * *

ONE DAY WHEN I was still a baby, not yet old enough to walk, my mother went out, leaving me in the care of my seven-year-old brother, Tommy, and nine-year-old sister, Polly. Before she left, my mother placed me in my walker. For a while, Polly, Tommy, and the two friends they had over played on the ground floor of our house while I gummed my hands and tooled around the kitchen island. Then, one by one, the older kids drifted outside. Maybe a half hour later, they found themselves together at Carl Carlson’s farm stand at the bottom of our hill. On the makeshift counter of his small shed, Carl sold penny candy; no one could resist a visit on the couple of days a week he was open. It took a little while, scrabbling over bubble gum and fireballs, before, with a sickening feeling, my siblings realized that nobody was watching the Baby. Racing back up the hill, Polly burst into the kitchen but couldn’t find me. After a minute or so, she heard a small moaning sound and followed it to the basement door. I was still strapped in my walker, but upside down on the concrete floor at the bottom of the rickety wood stairs. My forehead had swelled into a grotesque mound. My eyes were glassy and still. Cradling me, Polly and Tommy passed another stricken, terrified hour before my mother got home and rushed me to the hospital.

I’ve known this famous family story for as long as I can remember. But I was in my thirties before Polly confessed a detail I’d never known: our father was upstairs napping the whole time. Afraid for her own life as much as for mine, she couldn’t bring herself to wake him.

Until 1985, my father’s tempestuous spirit ruled our family’s private life as surely as his eminence defined the more public one. At times querulous and taciturn, cutting and remote, melancholy when he was sober and rageful when in his cups, he inspired fear and loathing in us a good deal more often than it feels comfortable to admit. But the same malaise that so decimated my father’s equanimity when he was depressed also quelled his inner storm when he recovered. In my adult years, he became remarkably mellow. A lion in winter, he drank less and relaxed more. He showed some patience, was mild, and expressed flashes of great tenderness for his children, his growing tribe of grandchildren, and, most especially, his wife.

He also managed, for the first time, to access some of his child-hood’s unexamined but corrosive sorrows. In 1987 my father wrote “A Tidewater Morning,” a short story in which he delivered a poignant chronicle of his mother’s death from cancer when he was thirteen. The story would become the title of a collection of short fiction, published in 1993, that centered on the most significant themes of his youth. During these years he also wrote several essays for The New Yorker, Esquire, The New York Times, Newsweek, and other magazines. He published a clutch of editorials; wrote thirty some odd speeches, commencement addresses, eulogies, and tributes; and traveled frequently to speak on the subject of mental illness.

As for long fiction, it was less clear what he was doing. (If there was a golden rule in our house when I was growing up, it was, unequivocally, “Don’t ask Daddy about his work.”) First and foremost, my father was a novelist. “A high priest at the altar of fiction,” as Carlos Fuentes describes him, he consecrated himself to the Novel. He wrote in order to explore the sorts of grand and sometimes existential themes whose complexity and scope are best served by long fiction. With a kind of sacred devotion, he kept at it, maintaining his belief in the narrative powers of a great story—and he suffered accordingly in the process. His prose, laid down in an elegant hand on yellow legal pads with Venus Velvet No. 2 pencils, came at a trickle. He labored over every word, editing as he went, to produce manuscripts that, when he placed the final period, needed very little in the way of revision. But, even at the height of his powers, this meant sometimes a decade or more between major works. Like that of a marathoner running in the dark, my father’s path was sometimes as murky as it was long.

* * *

THE AIR-CONDITIONED HUSH of the Duke library was, as always, a relief to me. Zach, my favorite student employee, gave me his familiar smile and nod, then passed a small lock across the circulation desk. If you’ve ever spent time in a rare book library, you know that the system for protecting its contents can be a little intimidating. You may not bring coats or hats, purses or bags of any kind into the reading room. No snacks or drinks, including water. Pencils only. And notebooks, but preferably without the complicated pockets or linings that might abet an act of smuggling, were you so inclined. White cotton gloves are provided for handling photographs. And at Duke, anyway, they’ll give you a sheet of laminated paper to use as a place marker, plus a folder for transferring documents up to the copier. When you leave, you’re subject to inspection. Notebooks are riffled, papers are stamped. It’s a polite but mandatory ritual, necessary for the safekeeping of all that is unique and fragile under the institution’s custodial care. When I started spending time at the library, I was struck by how curiously familiar it all was to me. Then I had a good laugh when I realized why: it’s a lot like the routines of a psychiatric hospital.

Taking a spot at one of the long wood tables, I flipped through the inventory list for the call numbers of the boxes I would need that morning. Up until then, I’d spent most of my time at Duke reading my father’s correspondence, trying to shake loose some memories of this man I’d rather impetuously agreed to write a book about. Somehow, in the time since his death, I’d mentally misplaced him. I thought if I heard his voice, sifted through his epistolary remains, he’d resurface—which he did, and then some. Not only had I begun to remember the father I’d known but I became acquainted with the son, mentor, and friend he was to others. In addition to the letters, I’d trolled through scrapbooks, magazine essays, interview transcripts, journals, audiocassettes, and all sorts of other ephemera. Being neither a scholar nor a critic, I’d written off my list the enormous cache of typescripts, proofs, and fragmentary monographic work that had been published before. After several months of work, there were only a couple more boxes of curiosity to me: “WS16: Speeches Subseries, 1942–1996,” and “WS17: Unfinished Work Subseries, 1970–1990s and undated.”

* * *

IN THE EARLY 1970s, shortly after the publication of The Confessions of Nat Turner, my father began work on a new novel. The Way of the Warrior, its title taken from the Japanese Bushido, or samurai code of conduct, was a World War II story. In it he hoped to explore the military mind-set, and his own ambivalence about the glory and honor associated with patriotic service. Just as the civil rights movement echoed in the themes of Nat Turner, my father’s new book, conceived during the Vietnam conflict, would, he hoped, gather force from the timeliness of its subject. But the central elements of the story failed to coalesce, and Daddy grew discouraged. Then, in 1973, he awoke from a powerful dream about a woman, a Holocaust survivor, he’d encountered while living in Brooklyn as a young man. Putting aside The Way of the Warrior, he quickly began work on his new idea. Six years later, Random House published Sophie’s Choice.

Just as some people can tag a family event by remembering what bank Dad was indentured to that year or which shift Mom worked, each phase of my youth is joined in my mind to the novel my father was writing at the time. I was twelve years old when Sophie’s Choice came out. Newly arrived on the shores of adolescence, I was acutely conscious of myself and my family’s place in the world. It seemed I’d been waiting my entire life for my father to finish whatever he was doing. With only the vaguest memory of Nat Turner, I’d begun to seriously doubt my father did anything really except sleep all morning and spend the rest of the day stomping in and out through his study door. So it was a huge personal relief to me when Sophie’s Choice was completed at last, validating my father’s years of work and, in the process, me.

If the story of Sophie played in the background of my schoolgirl years, my father’s book about the Marines set the mood through my teens. In the early eighties, after the hullabaloo surrounding Sophie had died down, he returned to The Way of the Warrior with renewed vigor. The project, his Next Big Book, took on a kind of stolid permanence in our home, like a sofa around which we were subconsciously arrayed. About this time, I left home, as my siblings had before me, for boarding school. And though I knew little about what my father was writing, it was useful to have the title. For the part of myself defined by his profession—and for anyone who asked—it was enough.

In its 1985 summer reading issue, Esquire magazine published “Love Day,” billing it as an excerpt from his long-awaited novel. My father was showered with mail, from friends and fans alike, the reaction immediate and overwhelmingly positive. The world had been put on alert. Bill Styron was at it again; great American literature would live to see another day.

And then he cracked up.

These days, the characterization of my father’s illness would be readily identifiable. But this was back in the Stone Age of clinical depression. The mid-eighties was not only a pre-Prozac world but one without any of the edifying voices that would cry out from the wilderness in the years ahead. There was no Kay Jamison, no Andrew Solomon, and, of course, no Bill Styron—no one yet back from the fresh hell of depression with any cogent field notes. So, like everybody else around my father, our family was mystified by his sudden spiral. By his paralytic anxiety, his numb affect, his rambling, suicidal ideation. He had everything going for him, didn’t he? Loving family, towering talent, money, friends. When, just before Christmas, my mother admitted him with his consent to the psychiatric ward of Yale–New Haven Hospital, we had absolutely no idea what would become of him. When he emerged two months later, declaring himself cured, we were just as quick as he was to embrace the diagnosis.

For the third time, he returned to The Way of the Warrior. I don’t know for how long he worked at it this go-round. Away at college by then, I was not only uninterested in my father but determinedly on the run from him, from my mother, from the whole crazy-town scene in which I was raised. Fulfilling my long-standing efforts to grow up as fast as I could, I’d move...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 1416591796

- ISBN 13 9781416591795

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages304

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.49

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # mon0000027118

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_1416591796

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1416591796

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 1416591796-2-1

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-1416591796-new

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1416591796

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1416591796

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1416591796

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Book Description Condition: new. Book is in NEW condition. Satisfaction Guaranteed! Fast Customer Service!!. Seller Inventory # PSN1416591796