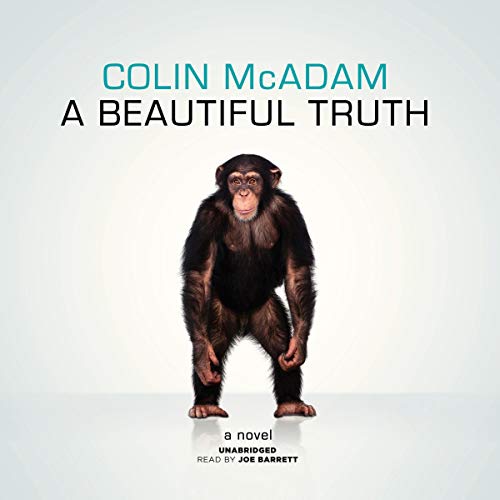

Items related to A Beautiful Truth

Synopsis

[Read by Joe Barrett]

Told simultaneously from the perspective of humans and chimpanzees, A Beautiful Truth -- at times brutal, other times deeply moving -- is about the simple truths that transcend species, the meaning of family, the lure of belonging, and the capacity for survival. Looee is forever set apart, a chimp raised by a well-meaning and compassionate human couple in Vermont who cannot conceive a baby of their own. He's not human, but with his peculiar upbringing he is no longer like other chimps. One tragic night Looee's two natures collide, and this unique family is forever changed. At the Girdish Institute in Florida, a group of chimpanzees has been studied for decades. The work at Girdish has proved that chimps have memories and solve problems, that they can learn language and need friends, and that they build complex cultures. They are political, altruistic, and capable of anger and forgiveness. When Looee is moved to the institute, he is forced to try to find a place in this new world. A Beautiful Truth is an epic and heartfelt story about parenthood, friendship, loneliness, fear, and conflict, about the things we hold sacred as humans and how much we have in common with our animal relatives. A novel of great heart and wisdom from a literary master, it exposes the yearnings, cruelty, and resilience of all great apes.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

COLIN McADAM's debut novel, Some Great Thing, won the Amazon First Novel Award in Canada and was nominated for the Governor General's Literary Award, the Rogers Writers' Trust Prize, the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for Best First Book, and the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize. His second novel, Fall, was short-listed for the Giller Prize and was awarded the Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize. He has written for Harper's and lives in Toronto.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

5

What do you see when you look at me.

The Girdish Institute had its origins in the 1920s, when William

Girdish made a trip to Buenos Aires. He had heard of a large private

zoo owned by a wealthy woman in that city, and it was there that

he saw his first chimpanzees. He was beguiled by them and endeavoured

to learn as much as he could about their nature and habitat.

He heard stories from the staff and zookeeper and witnessed their

obvious empathy and charming curiosity, and he bonded with one

in particular.

At dinners in the US he would tell stories from this place, like

the one about the chimp who developed an attraction to one of

the pretty cooks of the household. This chimp would watch her

in the kitchen from his cage with obvious desire, and over time

she grew unsettled by his attention. She asked one of the staff to

erect a barrier to his view, and boards were nailed to the outside of

his cage. The man with the boards who took away the sight of his

beloved was attacked a year later. The chimpanzee had harboured a

grudge all that time, and found an opportunity when the man was

doing repairs to the door of his cage.

Girdish set about gathering his own collection of chimps and

other primates, bringing them over to one of his properties in

Florida, near Jacksonville. He was a gentleman amateur, the only

son of a land-owning family, and he had property throughout

the South.

He believed that much could be learned from primates, chimps

in particular, that they were a link to our past and could explain

much of our behaviour. In this respect he was ahead of his time,

and there were few in the world who knew as much about apes

as he did. He travelled and sent envoys to Africa and housed a

growing collection of apes and monkeys in and around the greenhouse,

observatory and staff buildings of that property.

He established the institute and started a breeding program.

He developed a philosophy of what the ideal research subject would

be in terms of health, size and character. He and his colleagues

steadily developed tests, both mental and physical, which slowly

confirmed, in demonstrable scientific terms, how closely we were

linked to these creatures.

When he died in the 1940s he left a large endowment and his

work was carried on. Through the development of breakthrough

drugs the institute attracted funding from the federal government

and from companies around the world.

The old observatory and staff buildings were kept and it

was here that behavioural studies remained and the field station

developed. The new main building expanded and the biomedical

studies became the lucrative focus of the institute. But the beating

heart for many was the field station.

The original buildings had an Art Deco quality, soon hidden

by various additions. There were the sleeping quarters, which had

expanded over time, a winter playroom and a large safe area where

cognitive tests took place. There were kitchens, offices, bedrooms,

a garden which supplied some of the produce for the chimps, and

numerous old rooms whose purposes changed over time.

David Kennedy eventually became director of the field station,

and oversaw its expansion. Since the late 1970s you could say that

this part of the institute mimicked the life of a man. Its early days

were of directionless and unlimited enthusiasm and were shaped

over time by conflict, financial reality and the needs of others. When

David realized his personality, where his true interests lay, the field

station took its present shape. But while curiosity sometimes dies

and old enthusiasms seem foolish, the nature of the field station

prevented it from ever being static, and passion never diminished.

Even when the population settled, nothing was ever settled.

In vivid memory, his family were Podo, Jonathan, Burke and Mr.

Ghoul. Bootie, Magda, Mama and Beanie. Fifi and her open heart.

All the names he didn’t want to give them and the sadness that he

didn’t want to see.

David tells his assistants, when they first arrive, that they can

never choose favourites. Observe, but never judge. He knows that

it is an ideal—as if any ape can look without assessment: fruit is

never fruit, it is either ripe or rotten. People are never people.

He had an assistant once whose logs were always coloured by

her distaste for promiscuity. It was never simply Jonathan mounts

Fifi; there was always a hint of morality, a suggestion of wantonness

or assault. He sat her down and said do you have a boyfriend. She

was twenty-nine and had been married for seven years.

He said when you go home tonight and you find whatever way

you find to encourage your husband to hold you, make sure that

you forgive him.

His staff have come and gone in numbers. He has grown, he

hopes, more compassionate with age.

It’s a guideline, a piece of advice that David repeats, despite

himself. Try not to choose favourites, try not to dislike some of

them.

He brings prospective assistants out to one of the towers and

tests how quickly they can distinguish between the chimps. If

they have that rudimentary skill, he gives them twenty minutes to

observe a group. If the group seems peaceful and pensive and the

kids have fun, a bad observer will say they were peaceful and pensive

and the kids had fun. A good observer will say the alpha slept, as

did two of the females. Male chimp C sat near the moat as if on

guard, and the juveniles alternately rested and played. Male chimp

B, before he lay down, bowed to male chimp A (though asleep).

The females stayed closer to male chimp B as they rested. Female

chimp C would look towards sleeping male chimp B whenever the

juveniles made noise, instead of reprimanding them directly or

looking to the alpha, suggesting a possible shift in power.

Small things are big, every movement matters, morals blind us

to seeing the bigger picture, and if you don’t have the empathy to

watch for these things, get out of here.

But, at some level, it really was impossible not to judge. Their

talk over lunch was always about personalities. Who was mean and

what was wonderful.

Do you have a favourite, David.

He could rarely think of Podo without imagining some beloved,

long-reigning king.

Something about Fifi, who weighed two hundred pounds,

made him think of Farrah Fawcett.

And he had never met a chimpanzee as gentle as Mr. Ghoul.

6

Looee was quiet and still for over a month, waking only to feed

or if he felt Judy moving away. His lips quivered whenever she

put him down, though he was neither feverish nor cold. She knew

he needed the feel of her body and she felt his panic when she

saw him shiver. She rested him on her shoulder when she cooked.

Applesauce, candied carrots, everything warmed by stove, mouth

or hand till it held the heat of a body surprised by love. She crushed

bananas, scooped the purée with the tip of her little finger, felt the

tickle of his pink boy’s tongue as he sucked, the pull inside at her

feet, groin and heart.

Walt got sick and said I think I caught whatever it was he

caught, and Judy looked after them both. Walt was ever brave

before the wailing train of life’s horrific surprises, but he wasn’t

good with the flu. Judy he said, and nnn he said, and I feel sicker

than, and he rarely finished a sentence. He wondered whether it

was right to be sharing a bed with a chimpanzee and he dreamt of

eating prunes on a wavy sea.

New life was in the house. Two arms, two legs, grasping fingers,

inquisitive hunger, a shock from a dream that freezes the limbs,

subsidence into adorable sleep, and mouth on skin, he needs me I

need him to need me I need him. I’m tired. She slept.

She kept the fire burning into May and the house acquired a

sweeter, nuttier smell that was unpleasant to visitors. The bedroom

grew layers of terry cloth and tissue and she kept the bathroom hot

in case Looee needed warmth and wet for his lungs. Walt was hot,

Walt was cold, Walt was grateful and uneasy and finally hungry and

better. He explored the changing house and watched her cook with

their new friend over her shoulder.

He’ll hold your finger like a baby.

I know.

This house is hotter than inside a moose he said. Maybe it’s

time to crack a window.

The cloud of rheum, the film of incomprehensible memories,

was lifting from Looee’s eyes, and looking down was Judy. The

more his eyes cleared, the more curious and intimate Judy got.

Walt bought some toys like a ball and a doll and a bone. He

wondered what the hairy little guy could do.

These were the days that Judy, months later, remembered when

she sat on the living room floor and pondered the strangeness of

her life, how none of it seemed strange till now, and now there was

nothing strange, this was her little Looee. She fed him formula, not

plain old milk as Henry Morris had suggested. He was fifty percent

bigger in four months and Dr. Worsley was correct in figuring he

was smaller than normal when he had come to them. He figured he

was possibly a year, year and a half, who knows.

The loss of a mother and the travel from Africa typically killed

most chimps his age, but Judy’s presence saved him. Questions

naturally occurred to them about where he came from, what

ground, what air, but Henry and the circus had moved on. When

you plant a sapling, sometimes you don’t care where the seed was

from. They decided that as far as Looee was concerned, this was

where he came from, right here.

He slept in their bed for the first several months. Walt would

sometimes be awakened by Looee running his fingers through his

hair or playing with his lips and trying to pry his mouth open

with those little fingers of his, I’ll be darned. They always woke up

with him in the middle of the bed—he never liked anyone coming

between him and Judy.

The difference between Looee and a less hairy baby was that

he could move a lot better. He could support his weight, hang on

to things and climb. He never left Judy, but she could usually rest

her arms.

And he did enjoy a tickle.

Walt thought back to the laughing chimp in the circus and

figured Looee’s laugh was different. Looee’s laugh was real. You’d

get him on the bed and when you’d wedge your fingers into his

little armpits he smiled with his lower lip more than with his upper

and then he started this little chuckle like the uck in chuckle or the

ick in tickle but softer and Christ it was funny and cute. And he’d

stand up and squeeze your nose then throw himself down again

and away you’d go with more of a tickle on his belly and thighs,

Walt and Judy’s four hands on their little hairy piano.

He had pale hands, black fingernails, a pale face and feet, and

a little white tuft of hair on his rump that Judy liked to pat before

she put his diaper on. The hair on his body was a little wiry, though

Judy found ways to soften it up. There was a little boy’s body under

there.

He was squirmy in their bed and they didn’t sleep well for

a long time. Walt set things up for the future. It was a large old

house, with a couple of spare bedrooms that Judy had long ago

decorated with insincere finality. Solid desks for future business,

beds that only existed to display her latest linens. Walt took a big

oak wardrobe, laid it on its back and made a sort of crib.

They were happy to see that room change. Walt took a

chainsaw to the mattress and resized it so it would fit in the flatlying

wardrobe, and why they thought the walls of a crib would

contain a chimpanzee was part of a daily chorus of I didn’t think

of that.

He caused quite a fuss later when he had to sleep in his own

bed. He jumped on the dresser and kicked Judy’s makeup, jumped

down and halfway up Walt to hit his chest, and sometimes he

removed his diaper, smeared his mattress and returned with a look

that said you can’t expect me to sleep there it’s disgusting. He would

walk to Judy with his palm up and whimpering, and she was quite

susceptible to that. But Walt prevailed and Looee later loved his

bedroom and bed.

He hung around Judy’s neck or back throughout the day

watching everything she did. He slept a lot, but wouldn’t sleep

unless she lay near, and Judy cursed the noisy floorboards whenever

she snuck away. His screams when he awoke had a visceral effect

on her—she had no choice but to drop whatever she was doing

because it felt like either the world was ending or his noises would

make it end.

Sometimes he played on his own, but never beyond the

bounds of whatever room Judy was in and not for very long. He

was a toddler with the agility of an acrobat, so his play was usually

spectacular.

She had to think of him constantly—that’s what occurred

to her over the years as she looked back; that’s what soon made

him more than a pet. He wasn’t self-sufficient, he always needed

company—not just the presence of bodies, but society; he needed

the emotional engagement of others. There was no denying him.

You could step over Murphy on your way to doing other things

or tell him to shush if he was barking. With Looee you simply

couldn’t ignore him, and if he was complaining about something

it would have to be addressed with just as much care as with a

child. When Judy first used the vacuum cleaner, Looee screamed

and leapt onto her face. She had to turn it off, show him how the

power button worked and how the hose sucked up dirt. He was in

a heightened emotional state whenever it came out of the closet,

but he was soon able to turn it on, pull it around the house and

vacuum in his own way.

The truth was that Walt and Judy woke up most mornings

with the happy suspicion that something today would be new.

Despite her tiredness there was a new sense of vitality in Judy,

and as much as she sometimes yearned for peace she couldn’t

imagine returning to their old routines or waking up to days

without these fresh concerns.

You look rosier in the cheek said Walt. Let me kiss that.

There was a loss of spontaneity in their lives but it was more of

a shift than a loss. They couldn’t decide out of the blue to drive to

Stowe for dinner or make love on the couch with that surprise of

skin and heart. Looee had an especially uncanny knack for knowing

when they were getting close to each other, sensing the change of

energy between their bodie...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBlackstone Audiobooks

- Publication date2013

- ISBN 10 1482925362

- ISBN 13 9781482925364

- BindingAudio CD

- LanguageEnglish

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want