Items related to The Reasons I Won't Be Coming

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

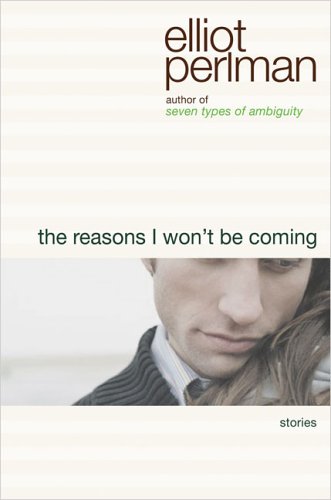

Elliot Perlman was born in Australia. He is the author of the short-story collection The Reasons I Won't Be Coming, which won the Betty Trask Award (UK) and the Fellowship of Australian Writers Book of the Year Award. Riverhead Books will publish this collection in 2005.

I am not well and I make no bones about it. It is largely a psychologicaldisorder, but only the most obvious of its manifestations haveever led me to hospital. These flights of fancy, as Madeline initiallywished them to be known, are actually psychotic episodes. But theseare just its most extreme symptoms. It is more than the sum of these.It is there all the time and no one knows what it is, a disease so new,so rare, that they haven’t developed a classification for it. They hadone briefly but the condition mutated beyond human understanding, beyond recognition. My work is said to compound the malady. I am,by profession, a poet.

When I cry I suck on my front teeth and purse my lips involuntarilyas though in anticipation of an onslaught of kisses. I never realizedthat I did this, never even suspected it. It is a mannerism justshort of a tick and it belongs to me. There is a rhythm to it and I rockslightly in time with the pursing of my lips. I do this all in time. Thisrhythm is a matter of instinct with me. I am a poet.

How does that happen? In spite of everything, how does one becomea poet? The term has become derogatory. How did that happen?It all happened before Madeline’s father died. These days people assume,if ever they give it any thought, that poets must be inept,glassy-eyed people who, tyrannized by their own private internal anarchy,ramblingly conjure instant affect. But that, of course, is a stereotype.And it all starts way before this.

You are born. You remember nothing of it but get told at selectedintervals that yours was a traumatic birth. The nature of the traumadoes not really matter. What matters is that you are told about it atan early age. It quickly assumes a tremendous significance in yourown private mythology. You visualize it in gray or sepia as a scenefrom a prewar newsreel. As you grow up you use it to explain otherwiseinexplicable and unjust events. It is why you cannot perform certaintasks as well as other people, or at all. It is why your mother wasthis or that way with you.

You read, not just well, but powerfully.

You do just well enough at school for your distraction from whatother people are interested in to be encouraged once, briefly, by asympathetic teacher who, by the time you timorously graduate, hasleft the school and cannot be reached.

You read more.

You get a clerical job and study literature and history or philosophy,classics or art history at night. At work you meet an attractiveyoung woman from the country. You flatter her. She flatters you. You write a poem about her. You tell her it is your first but it is not. It isactually just the first poem you have ever shown anyone. She is yourfirst, the first to see it. But the poem is not your first. The others, theearlier ones, were naïve, derivative and masterfully bad. This one, too,is bad, but you show it to her because otherwise, without it, in its absence,you are a clerk. It works and you are a poet.

You spend time together. You take each other to art galleries andmuseums. You teach her and then recite in unison the opening to“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T. S. Eliot:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky.

You get promoted. There are more art galleries. She gets promoted.There are more museums. You drink strong coffee, almost professionally,in the inner city area. She encourages you to submit the poemabout her for publication. She tells you she has never met anyone whowrote poetry. You suspect that it is just that she has never met anyonewho admitted it. You think everyone writes poetry. The poem abouther is published. You share a kind of delight.

You meet other people who have published poetry. You take her totheir poetry readings. The two of you drink coffee with them after theirreadings. You get promoted again. She knits you a jumper. You meether parents during a weekend at their cattle farm in the country. Onestill night you tell her about your traumatic birth. You get married.

You are married. She gets promoted. You write a volume containingmany poems. Two of them are published. She gets promoted.There are more museums. She gets pregnant. You write some poemsabout it. She takes maternity leave but not before being promotedagain. A child is born. In many senses he is yours. Andy. You writePoems for Andy.

Andy grows to learn Christmas carols, and when he is old enoughto sing them, you change the lyrics outrageously. You change their meaning. You take away their meaning. Rudolph the red-nosed reindeerhad a very shiny name. It is a game. It delights him. It is the lasttime you remember delighting him. She gets promoted.

You take him to museums. You write a poem about museums,about taking your son to museums, about the ways in which museumsrecord time. You used to go there with your wife. Later she sendsyou there with her son. He continues growing. “What are you feedinghim?” colleagues ask at work Christmas parties. Too big for yourknee, you recite to him across a room: Twinkle twinkle little bat! How Iwonder what you’re at! Up above the world you fly, Like a tea tray in the sky.Too big for Lewis Carroll, there is so little in him that resembles you.Your parents die. It affects you more than certain acquaintances thinkit should. She gets promoted.

Your son grows. Up, up and away! He plays different games. Hegrows more like his mother, at least more like her than like you. Theyshare a certain closeness you attribute to the famed bond betweenmothers and sons and also to your traumatic birth. She tells you shedoes not want any more children. You write a poem about this. It ispublished in Meanjin. It is anthologized. The anthology becomes aprescribed text for secondary students. Of the six years your son spendsat secondary school, fifty minutes are devoted to poetry. The anthologyis for a moment in your son’s hands. One book between two. It isan austerity measure. He does not see you waiting in the table of contents.They read Kipling. At work you are made redundant. Still notold, you read ever more. She gets promoted.

Your wife’s father dies and bequeaths her the farm. She resignswith a large payout. Your son leaves home. You and she return to herroots to run a cattle farm. She tells you it might be good for you. Youare so pleased to hear that she wants it to be good for you that you donot question the move. You know nothing about farming or cattlebut you can write poetry anywhere, if indeed you can write it at all.You picture a new rural phase with rural themes. Wordsworth meetsTed Hughes and Les Murray. You aim to keep in touch with the literary community through the membership of committees. You plan tobe a literary agitator. You will write angry but witty pieces denouncinggovernment funding cuts to the Arts. “Your Tiny Handout Is Frozen.”

The year that Madeline and I moved to Mansfield was the year thatAndy and one of his friends bought a four-wheel drive to take aroundAustralia. He was by then already a big and practical young man,good with his hands. All the girls liked him. He had not wanted togo on to university. He did not have any plans for the year after thefour-wheel-drive trip. He told me this quietly as we shared a cup oftea on the verandah the day he drove up to Mansfield to say good-bye.It was, I thought, a defining moment in his development, and it occurredto me that it should have been acknowledged with some sortof going-away party. But we were new to the area and, other than thepeople Madeline knew from her youth, we did not know anyone to invite.He would have hated the idea anyway. He spoke quietly in a low,soothing, anxiety-free voice. He did not read. I thought that maybehe would when he got older. He could do everything else. He had declinedseveral offers to play a number of sports at a professional level.Madeline and I were so proud of him, so proud of his balance. I suspectthat he already thought I was mad.

Mansfield was settled in the 1870s and soon became home to familiesof Irish and Scots settlers. Madeline’s family, of Scottish descent,had been there for generations. “The best ones had packed up andleft,” she had always been told. They were farming people. Madelinehad been the first to move down to Melbourne, but her father’s deathand my unemployment convinced her that it was time to return. Herchildhood, or what I knew of it, had not been an unhappy one. Thewhole Shire, and not just her father’s property, was full of memoriesfor her, memories, and roads not taken.

By the early nineteenth century the first European explorers hadfound the soil to be rich. There was an abundance of grass, excellent for grazing cattle or sheep. (Our neighbor grazed sheep.) But even sothere was initially some reluctance to settle it. Perhaps it was the influentialopinion of the then Surveyor-General of New South Wales,who described much of the region as “utterly useless for every purposeof civilized man.” Madeline said time stands still in Mansfield. Herfamily was born and died there, so it had not stood still for them.Something I refrained from pointing out. Andy and I had only beenthere once.

Madeline’s father had employed a young, newly married neighborof his to assist him with the running of the farm, and on our arrivalMadeline and I immediately appointed him manager of the farm. Herfather had needed only his physical assistance, but I needed a fulltimetutor. His name was Neil Mahoney. In his early thirties, he wasthe youngest of a large family, large enough to spare him from workinghis parents’ property. His wife was almost ten years younger thanhim and, within a year of his becoming our manager, was expectingtheir second child. Madeline had heard that it had been difficult forNeil to find a wife because the Mahoneys had too many sons for theiracreage. It was said they would overgraze. Two older Mahoney boyshad left Mansfield for Melbourne only to return, having been unableeither to find or hold on to jobs. Now they were both married and, togetherwith Neil’s father and an older sister’s husband, they all workedthe Mahoney farm.

Neil was patient with me, patient in his explanations and hisdemonstrations. In return I was honest with him. I told him I was apoet who had tried to support himself and his family as a clerk. I wasalso an occasional essayist, I told him. (This was not completely untrue.I had written one unpublished essay titled “Critical Theory as aMetaphor for Illness.”) I tried to be unafraid of my mistakes or at leastfaithful to them. I had never been a farmer before and was not meantto know the things he was teaching me. But despite this I still had tofight the feeling that he thought I was a fool. He watched me.

It was not anything that he said, but I felt a little uncomfortable with him. It was an unease that never really disappeared completely.Each time I felt uncomfortable in my role as a farmer, I would forcemyself to write something, even if it was just a letter to a newspaper.I composed verse in my head while examining the fences with Neil orhay feeding the cattle during winter. I learned that, despite the rain,it was too cold and dark in the winter for the grass to grow. Weneeded the grass to grow to feed the cattle to support ourselves. Neilworried about the weather and the grass all the time, but I never did.After all, if the grass did not grow, no one could fairly blame me.Madeline could not blame me. I did not think she could blame me.

She found in me something to blame when I returned from thetown one day with three kittens. They were a gift for her. I hadbought them from the younger sister of the bored and sullen teenagegirl with scrambled-egg hair who worked at the Welcome Mart.Where the older girl at the Welcome Mart had made a weapon of heradolescence, the younger girl had not yet given up on adults andwould talk with them in the street. She would even offer them herkittens for sale.

“People don’t keep kittens in the country—not here,” Madelinetold me when I surprised her with them in a canvas bag the younggirl had thrown in at no extra cost.

I thought she might warm to them if I left her alone with them. Inthe shed I found Neil cleaning a rifle. He seemed to know what he wasdoing, yet again. I knocked tentatively in order not to surprise him.

“Is that your gun, Neil?”

“No, it’s yours. It was your father-in-law’s.”

“What do we need a gun for?”

“For killing things.” He looked up at me.

“Like what?”

“Animals that need to be put down . . . cattle . . . all sorts of things.You just never know.”

There was so much I did not know. What I knew was of no use tothe people around me. Perhaps it was of no use to anyone. And I did not really know it. It was more that I had heard it. Lines, words,snatches of poems, came to me and then from me. I was merely a conduitfor them. What did they have to do with me? Mostly they werenot even my lines. I could be in a field and suddenly I would be unableto rid myself of Eliot or Wordsworth or Shakespeare. Increasingly,however, it was something from the Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam.His lines, more than any, got me through the day. They hummed tome. Eventually I could not get rid of them.

If you are voluntary, they let you keep your own clothes. This was themost obvious difference between the first and the second time. Anotherwas that I did not know how I got there the first time. I wasthere when I woke up. I was lying on a bed with tubular steel railingaround it. My pajamas, the sheets and the pillow cases were a standardblue, all with a Department of Health logo on them. The bednext to me was unmade. The mattress was covered in vinyl and hadbrass eyelets over which there was a thin metal gauze. Two beds downfrom me a man lay on his front, trying to fit all of his face on the Departmentof Health logo on his pillowcase. He wore blue pajamas too.We were not voluntary.

I tried to remember how I got there but could not. I had been inthe car with Madeline. She was driving. It was a long drive. We weregoing to Lake Eildon. The kittens slept huddled together in the backseat.Madeline turned off the radio after we had driven a short distance.I noticed she was not in her usual sloppy slacks but was insteadwearing a dress. I remember she was wearing a brooch.

“Why do you have your good clothes on?”

She shrugged and kept her eyes on the road.

“I had an uncle who used to tell us, ‘Always wear your worstclothes.’”

“Why?” she asked without looking at me, still with her eyes onthe road.

“You have more of them. ‘Don’t be tempted into wearing yourbest clothes,’ he’d say. ‘Save them for a better occasion. If ever you findyourself wearing your best clothes, it means you’ve admitted to yourselfthat it’s never going to get any better than this.’ They buried himin his best clothes.”

“That’s not true,” Madeline said, both hands on the wheel.

“No, it is. I had an uncle and . . . he’s . . . he’s dead now. . . . Butit’s like the title of that book by Yevtushenko, prose, not poetry, Don’tDie Before Your Death. Yevtushenko’s telling us to wear our best clothesbefore it’s too late. He’s got a remarkable spirit, that man. I met him,you know, in Melbourne.”

“I know.”

“Few years ago now. Told a great story. Well, more than one, butthis one concerned a poor Russian peasant who tried to save what littlemoney he had by training his horse to eat less and less each week.With every week the peasant fed his horse a little less than the previousweek.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRiverhead Books

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 1573223212

- ISBN 13 9781573223218

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 5.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Reasons I Won't Be Coming

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. AUTHOR SIGNED nf/nf (as new) 1st printing hardcover in mylar protected dustjacket. First US edition. As new; not remaindered, not bookclub, dj price intact & full numberline. Simple author signature, no inscription. fiction. Language: eng. Signed by Author. Seller Inventory # 9027

The Reasons I Won't Be Coming

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1573223212

The Reasons I Won't Be Coming: Stories (Signed First Edition)

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. First edition. First printing. Hardbound. NEW! Very Fine/Very Fine in all respects. SIGNED by author on title page. He has signed his name only,m without any inscription. A pristine unread copy. (Smoke free shop; no marks or defects). All books shipped in well padded boxes with bubblewrap. You cannot find a better copy. Signed by Author(s). Seller Inventory # bbsjan06-1

THE REASONS I WON'T BE COMING

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1. Seller Inventory # Q-1573223212