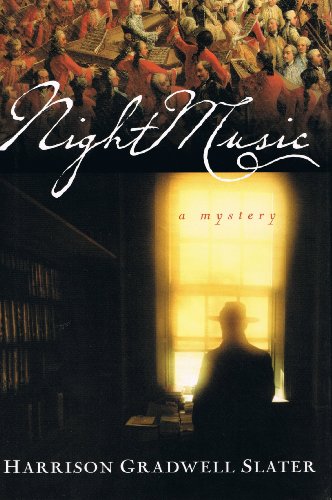

Items related to Night Music

If authentic, the diary could catapult Matthew Pierce into wealth and fame. His search for the truth leads him into a dazzling world of Europe's wealthiest and most gifted musicians and aristocrats. But the brilliance of his surroundings is clouded by intrigue, threats, and murder. Matthew becomes both searcher and prey, and the peril mounts. Traveling across Europe with an entourage of divas and gentry, Matthew unravels the fiendish plots that threaten him and his friends, while giving us the Mozart diary, a new and delightful insight into the world of one of the greatest musicians ever to have lived.

Harrison Slater, internationally known Mozart scholar and performer, makes a terrific debut into the world of literary mysteries.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The life of every man is a diary...

-J. M. BARRIE

At the ticket window in the central station, there was a huge line of anxious, impatient travelers, mostly Italian. When I finally reached the counter, the agent informed me, "Trains heading south are running several hours late." Standing behind me in line, a traveler accustomed to the caprices of the Italian railways added that he had heard a group of disgruntled workers had blockaded the tracks at Salerno with their own bodies.

"Nothing serious," the agent at the window concluded. "Just the usual Christmas strike." But to me it suggested serious delays, and I envisioned spending hours in an immobile train packed to capacity with restless holiday travelers.

"The best thing to do?" I asked.

"Wait a day and see what happens," the ticket agent replied, and the veteran traveler concurred.

After checking into a small hotel, I crossed the street to Via Mecenate, where the windows of a large auction house caught my eye. A preview was taking place and although I suspected I would be gone by the time the items were auctioned, the quality and number of antiques were imposing enough to capture my imagination, and so I entered. Spread out over many rooms was an infinite number of impressive pieces: inlaid period furniture, marble busts, and eighteenth-century engravings, all competing for the eye. In a room dedicated entirely to leather-bound volumes and illuminated manuscripts, I noticed a dusty archival folder marked "di scarsa importanza" (of little importance). Untying it, I found a thick stack of tawny ochre pages covered with columns of script and numbers penned meticulously in Italian. The random words olio, vino, and legno-oil, wine, and firewood-caught my eye, indicating that the pages were a balance sheet for household expenditures. As I proceeded through the stack, the color of the pages shifted gradually to ashen gray and I began to detect a musky stench, the smell of damp paper.

In peeling the layers apart, my hands were continuing to search long after my mind had decided that I had better things to do on my vacation. But my fingers persisted in their silent hunt, since I realized that the folder, after making it through so many centuries, could easily end up in a Dumpster if no one bought it.

The ink, a rich sepia, glistened with a syrupy viscosity, and the enigmatic quality of the leaves and layers intrigued me. Dampness had weakened the folios, but the paper was from virile stock-much like the rich, sturdy pages used today for artistic writing paper and fine private editions from exclusive bookmakers-and seemed to have stood up to the ravages of time. After prying apart a new layer, I was surprised to find myself staring at a set of pages completely different from the anonymous ledgerlike household accounts that preceded them; these were not in Italian, but in German.

As I peeled back another page, a name caught my eye: Nannerl. The name was so special-the nickname of Mozart's sister. In fact, I realized I had never heard of anyone else using the name Nannerl. But my thoughts were interrupted when I spied numerous tiny burrows and tunnels traversing the pages, apparently made by worms eating their way through the layers. An involuntary shudder swept through my body as I searched for a date, aware that I might at any moment unpeel a page and find one or a dozen of the voracious creatures squirming and wriggling before my eyes.

The mere glimpse of the name Nannerl triggered a flood of impressions. In some ways her life had been unfortunate; she had been a child prodigy on the harpsichord, but the extraordinary abilities of her younger brother gradually eclipsed her own talent and usefulness. Although she had appeared before the sovereigns of the greatest courts in Europe, she was eventually relegated to staying home in Salzburg with her mother while her father, Leopold, traveled with Mozart to Italy in search of fame. Attractive, well mannered, and educated, she was prevented by her father from marrying the man she loved in favor of a nobleman who was almost twenty years older. And she died alone, almost blind and in poverty. The birth of a genius in her family had proven both a blessing and a curse.

Despite the damage, the pages were almost pristine: no smudged edges, no signs of reading and rereading. In fact, I had the distinct impression they had never been touched. When I found the scrawled date, "January 24, 1770," my mind shut down momentarily and my heart began to pound. Looking around surreptitiously, I tried to see if anyone had noticed my reaction, but customers were too busy discussing how items would look in their apartments, and the sales and security personnel were too interested in guarding small silver objects on display.

To avoid attracting attention, I resisted the temptation of reading through the folios and debated canceling the rest of my trip, which had been undertaken at great financial risk. Not having received any word about several job prospects, I had decided to toss caution to the wind and buy an airline ticket on my last credit card. And I was now paying my travel expenses with the remaining trickle of available credit. All because I had come to realize that Europe-that rich, elusive sanctuary of Western art and culture-was necessary to my existence. For years, my precarious financial situation kept me from traveling outside America. But I had begun to wonder what the purpose of all my hard work was. Unwisely, and regardless of the consequences, I had put up my last dollar to travel, and now I was considering giving it up in midstream.

Somehow the innocuous little stack of papers made sense of it all. The prospect of a serendipitous discovery sent a wave of optimism racing through me: for once, fate was smiling on this impoverished, unemployed scholar. Briefly, I even imagined a few lines in the Associated Press, an event that could give me an edge over hundreds of other candidates for a permanent teaching position.

Maybe it was all just by instinct but I decided to cancel the rest of my trip. After all, even established, well-paid university professors would do the same thing. And if the diary were authentic, nearly any one of them would kill for what I had in my hands.

On the evening of my fourth day in Milan, I arrived early at the imposing, frescoed auction room, where seventy or eighty buyers were seated. A huge lot of inlaid Italian furniture from the time of Louis XVI immediately drew intense activity, followed by keen interest in a splendid oil painting of the Madonna by Murillo. The language in the room was unknown to me: a pen or an index finger raised aloft almost imperceptibly, a brief raising of the chin or a subtle nod. After an hour and a half, the grimy folder that had caught my attention came up for bid, and I waited in the uncomfortable silence while the auctioneer opened the bidding at dieci...ten euros. About ten dollars.

The moment he was ready to move on, I said, "Dieci," using my best poker voice.

After a painfully silent pause, no one was interested in making a higher bid. "Once, twice..." the auctioneer announced.

"Venti." Glancing over my shoulder, I saw an extraordinarily well dressed man with a thick black mustache who raised an eyebrow when my eye caught his. Was he a professional, hired to push up the bidding? Or was his curiosity suddenly stimulated by a foreigner bidding on a worthless stack of papers?

My heart suddenly pounding, I hesitated to respond too quickly. "Trenta," I finally said. It was only about thirty dollars, but I realized I could soon find myself outside my possibilities for bidding.

After a pause, I heard, "Cinquanta." Raising his bid to fifty dollars, it seemed as if the only other bidder was playing a game with me. Although I tried to be inconspicuous as I examined the contents of my wallet, I sensed every eye in the room was riveted on me.

"Cinquantacinque," I responded. About fifty-five dollars.

"No, Signore," the auctioneer replied in Italian, with a reprimanding tone. "Dieci is the minimum bid."

"Scusi," I replied, apologizing, furious that I hadn't thought of bringing more cash. "Sessanta." Sixty dollars.

The next half minute was excruciating. With my temples pounding, the silence was interminable. The ear-splitting rap of his gavel on the desk struck me with the force of a thunderbolt. "Aggiudicato!"

That's me! I suddenly realized, I have it. Looking over my shoulder, I caught the eye of the impeccably dressed Italian, who shrugged his shoulders casually, with an ironic expression.

My precious, unexplored trophy held tightly under my arm, I exited quickly, with a slight degree of paranoia, as if an invisible gauntlet of pickpockets was poised and waiting. Walking back toward my hotel, I was both ecstatic and skeptical. Had I just been scammed by a professional bidder into paying my entire week's budget for a stack of worthless papers?

The massive paving stones of the Piazza Duomo, just washed, glistened with a tired dignity, and it surprised me to see hundreds of people out at night, crowded into cafés, huddling in small groups, smoking or enjoying a leisurely stroll after dinner, just as incalculable generations before them had done. Bright lights illuminated the facade of the immense Gothic cathedral, giving the impression of daylight. Detail, so much detail, overwhelmed the exterior, a masterpiece of mannered, cluttered elegance. Sculptures of transcendental lightness, thousands, competed for attention, and tons of stone hewn into lace soared above me, more like fragile paper cutouts than marble. And from the highest pillar, a tiny gold Madonna looked down upon the mad frenzy beneath her with helpless incomprehension.

Near the cathedral was the entrance to the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, a massive structure of glass and wrought-iron filigree reminiscent of some great nineteenth-century horticultural exhibition. At a small indoor café, I ordered the house aperitif and then stopped short. Checking my remaining cash, I quickly changed my order to una piccola birra alla spina, a small draft beer, realizing I couldn't even afford to leave the waiter a tip.

Slowly, I began to evaluate my newly acquired treasure. Again I unearthed the folio dated January 24, 1770, and tried to remember where Mozart was living at that period of his life-an easy task thanks to Leopold Mozart, who had planned to write a biography of his famous son and had chronicled and documented his life more than that of any composer in modern history. Mozart was born in 1756, so I calculated he would have been about fourteen years old in 1770, and in Italy for the first time with his father, where they hoped to secure a commission for Mozart to write a serious opera for the theater that preceded La Scala opera house.

Although the weight and quality of the paper suggested that it could have come from the eighteenth century, I returned to the folio that had caught my eye with a more critical, even skeptical, approach and started to make a careful transcription of the text.

January 24, 1770

This journal will, of necessity, be brief. It will be my silent companion and faithful confidant. It will be the only possession that is mine alone, the one part of my life that is truly my own.

Papa is in the next room discussing practical matters with two gentlemen. He knows my usual pace in composing so it would not be wise to spend too much time on this diary. For this reason, my journal will have to be comprised of short passages.

Perhaps a diary is the only way to understand the many feelings I am experiencing. After all, we are alone in Italy for the first time, without Mama and Nannerl, and the sense of freedom is exhilarating. My impressions of this new world are too powerful to suppress, they burst from my pen like themes flowing from my fingers at the keyboard.

Papa would certainly disapprove of my "ill use" of the gifts God has given me in my writing a diary instead of a new composition. But he himself keeps a precious book of notes, and his weekly letters to Mama are just like a journal, carefully preserved each week in our heavy wooden chest in Salzburg. Why should the same privilege be denied me?

Each day a ferocious thought returns to torment me: I have been denied a great deal. Over and over again, I hear, "The most fortunate, the most blessed of children. A miracle, a gift of God." All this and more. Yet something has been missing for a long time: my childhood evaporated like snowflakes on the windowpane. Like an inquisitive bird peering from the nest, I desire to spread my wings. And I fear the inevitable, that the days of my adolescence will be denied me as well.

Papa insists that the tailor, the wigmaker, and even the artist who just painted my portrait emphasize my youth, and he has even told people that I am younger than my true age. Yet, regardless of his determination to portray me as a child, since our arrival in Italy, I have become a man, and nothing Papa can do will ever change that.

As I leafed through the folios, a mounting rush of excitement surged through me: discovering a Mozart diary could be my first big break, my chance of establishing a foothold in the tight, closed world of academia. Somehow, all the struggles to make ends meet now seemed worth it-the nights researching and writing until 2 A.M., knowing that I still had to prepare music classes for the next day. Perhaps the meager times were coming to an end. The diary began to represent that elusive, seductive light at the end of the tunnel.

The text of the document was certainly credible since, at that time in his life, Mozart consistently referred to his father, Leopold, as Papa. And what a father Leopold was: a renowned educator who supervised every aspect of his children's development and a keen businessman who controlled every detail of the many journeys made with Mozart. Perhaps, as the diary suggested, he controlled too much and too successfully. But the material was convincing-either it was the work of an expert forger who knew Mozart's life well, or I had stumbled onto something authentic.

It was my last night in Milan, so I was reluctant to surrender myself to the barren, unadorned walls of my hotel room. Instead, in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, I was immersed in a world of frescoes, mosaic floors, and sculpted ornaments, lit theatrically to evoke space and perspective-a stage set of scrolls, shells, and sculptures and of tiny wrought-iron balconies where no one could walk. And the Galleria was overflowing with a vibrant celebration of life.

It was time for me to make an important decision: whether to try my luck with the diary in the lucrative commercial world of international auctions or in the academic world. Unfortunately, my life in the world of academia had brought nothing but disappointment. I thought that my total devotion to Mozart, music, and my students would mean something. But by now, my career had become a nonstop odyssey-traveling from one single-year appointment in musicology to another, always in places where no one wanted to live, always for a pitiful salary. Sometimes tenure was offered as the proverbial carrot and stick, but in reality, universities periodically fired me before that could ever take place, as they did everyone else. Hiring junior faculty simply cost less. It was all a painful blur, a nightmare I needed to forget in order to go on, to survive.

Of course I had to take some of the blame for my lack of success in academia. I had refused to play the game, to treat pompous and arrogant professors the way they expected to be...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHarcourt

- Publication date2002

- ISBN 10 015100580X

- ISBN 13 9780151005802

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages576

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Night Music

Book Description New Hardbound book w/dust jacket. 2002 ~ FIRST EDITION COMPLIMENTARY DELIVERY CONFIRMATION INCLUDED. Binding tight. Boards clean, straight and edges sharp. Dust jacket in great condition, price intact, clean and glossy. Pages crisp, clean and unmarked. No remainder mark. Ships within 24 hrs except for Sundays and Holidays. Thanks for supporting a small family business. Seller Inventory # VW-8XVR-ZPMD

Night Music

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. Brand new, never sold, first edition first printing, full letter line, no remainder marks. Ships in a box, fast service from a real bricks and mortar independent bookseller open since 1998. Seller Inventory # 009757

NIGHT MUSIC

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.99. Seller Inventory # Q-015100580X

NIGHT MUSIC

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.99. Seller Inventory # Q-015100580x