Items related to Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African...

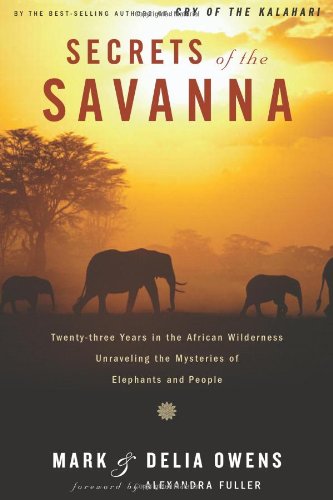

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People - Hardcover

Crossing stick bridges over swollen rivers and battling swarms of tsetse flies, Mark and Delia Owens found their way into one of the most startlingly beautiful, wild places on earth, the northern Luangwa Valley in Zambia. As they were setting up camp to launch their lion research, gunfire echoed off the cliffs nearby. Gangs of ivory poachers were not only shooting the elephants but also virtually enslaving local villagers. Against unimaginable odds, Mark and Delia stopped the poaching by helping the villagers find other work, start small businesses, and improve their health care and education.

Living with wild creatures all around (lions sleeping at their toes, an orphan elephant dancing a jig in camp), Mark and Delia observed surprising similarities between the behaviors of humans and those of other animals. The bonding among young female animals and the competition among males reminded them of their own childhoods. As the elephant population slowly recovered from poaching, the Owenses saw parallels to human societies under stress. Older elephants, killed for their tusks, had taken with them the knowledge that had been passed down to the young for generations. The slaughter of the elders led to chaos -- single mothers without older females to guide them, solitary orphans, rowdy gangs of young males -- and a scientific mystery: how could there be so many babies and so few females old enough to be mothers? A young orphan they named Gift eventually provided the clue to the remarkable discovery that revealed the elephants' secret.

After the local ivory poachers were put out of business, they shifted their sights from the elephants to the Owenses. To save themselves, Mark and Delia took a lesson from the elephants, employing one of the last secrets of the savanna.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

A gift into the world for whoever will accept it.

Richard Bach . . . there are conflicts of interest between male and female in courtship and mating.

J . R. Krebs and N. B. Davies

Between the trees of the forest, amid the thorny undergrowth, under tangles of twisted twigs is a space that is more color than place. It is a grayness painted by drooping limbs and distant branches that blur together and fade into nothingness. It is not a shadow but a pause in the landscape, rarely noticed because our eyes touch the trees, not the emptiness on either side of them. And elephants are the color of this space. As large as they are, elephants can disappear into these secret surroundings, dissolve into the background. When poachers slaughtered the elephants of North Luangwa, the few remaining survivors slipped into the understory. They were seldom seen and almost never heard because they rarely lifted their trunks to trumpet.

When we first came to the Luangwa Valley we could barely grab a glimpse through our binoculars of the elephants’ broad, gray bottoms and thin tails before they tore into the thick brush and disappeared. As poaching decreased, a hushed peace settled over the valley, like the silence of fog folded among hills at the end of a rain. In 1991 fewer than ten elephants were shot in North Luangwa, down from a thousand killed illegally every year for a decade. It was an unexpected yet natural quiet, as if a waterfall had frozen in midsong in an ice storm, leaving the land humming with the soft sounds of life. And then, once again, the elephants began to trumpet.

Slowly, beginning with Survivor, then Long Tail, Cheers, Stumpie, and Turbo the Camp Group a few of the male elephants learned that they were safe near our camp, Marula-Puku, which we had built in a large grove of marula trees on a small river, the Lubonga, halfway between the massive mountains of the escarpment and the Luangwa River. The elephants came at all times of the year, not just when the marula fruits were ripe. Sometimes they turned their giant rumps to our thatched roof and scratched their thick hides on the rough grass, closing their eyes in what appeared to be the most blissful glee. Elephants can make a lot of noise while feeding, tearing down branches or pushing over medium-size trees, or they can feed as silently as kittens, munching on fruits for long moments.

One night, as Cheers fed on one side of our cottage and Long Tail on the other, both only a few yards from our bed made of reeds, they let forth with full vocalizations. Mark and I, shrouded in our mosquito net, sat up as the sounds shook us. A lion’s roar pounds the chest like deep sounds reverberating in a barrel; an elephant’s trumpet, especially after decades of being stifled, stills the heart.

In the years before they learned to trust us, they must have watched from the hillsides, remembering the fruits of the marula grove yet afraid to come near. But once they made up their minds that we were harmless, nothing we did seemed to bother them. No matter whether Mark flew the helicopter low over the treetops, or our trucks rumbled in and out, or we cooked popcorn on the open fire, the elephants came to camp. When we stepped out of our cottages, we had to remember to look carefully both ways, or we might walk into an elephant’s knee.

That nearly happened one dark evening when Mark walked quickly out of our open, thatched dining n’saka, or gazebo, where we were eating a dinner of spicy beans by candlelight. He was headed toward our bedroom cottage to retrieve the mosquito repellent and, having his mind on other things, played his flashlight beam along the ground looking for snakes. He heard a loud wooosh and felt a rush of wind. Looking up, he saw an elephant’s chin and trunk swishing wildly about against the stars. Cheers stumbled out of Mark’s path, twisting and turning to avoid the small primate. Both man and elephant backpedaled twenty yards and stood gazing at each other. Cheers finally settled down. He lifted his trunk one last time, flicking dust in the flashlight beam, and ambled to the office cottage, where he fed on marula fruits, making loud slurping sounds.

The elephants were not always so amiable. On a soft afternoon when the sun was shining through a mist of rain, I was reading in the n’saka by the river. Cheers marched briskly and silently into camp and fed on fallen marula fruits next to the bedroom cottage some thirty yards away. For a while he and I, alone in camp, went about our work, only glancing at the other now and then. The occasional heavy drop of rain fell from the trees as the mist cleared, and a faint wisp of steam rose from Cheers’s broad, warm back. Thee picture was too beautiful to keep only as a memory, so I decided to photograph him. To get a better view, I tiptoed out and stood under a fruittttt tree not, as it turned out, a good place to stand in marula season. Suddenly Cheers turned and walked directly toward my tree. Within seconds he was only fifteen yards away. Surely he had seen me, but he came on purposefully, his massive body swaying, as though I weren’t there. I was unsure whether to stand or run, but Cheers was not the least bit indecisive; this was his tree, his fruit. Flapping his ears wildly, he mock-charged me. I ran backward about ten yards, turned, and jumped off the steep bank into the river, where Ripples the crocodile lived.

Even as the poaching decreased, the small female groups the remnants of those once large family units were shyer than the males. Finally, after several years, one or two females with their young calves would feed on the tall grass across the river, not far from Long Tail or Survivor. But they never ventured into camp, just wandered nearby and stared at us from the bluff above our cottages. Their backs glistening with mud, the youngsters would splash in and out of the river and romp on the beach across from the n’saka.

To keep out the African sun, we built our camp cottages with stone walls fourteen inches thick and roofed them with thatch about two feet deep. The huts stayed cave-cool even when the dry-season heat exceeded one hundred degrees. One afternoon, as I sat in the dim office cottage analyzing elephant footprint data on the solar-powered computer, a soft knock sounded on the door, and I looked up to see Patrick Mwamba, one of the first four Bemba tribesmen we had hired, years before, at the door. When he first came to us asking for work, the only tool he knew was his faithful ax; now he was our head mechanic and grader operator. Patrick is shy and gentle, with a fawnlike face.

Dr. Delia, come see,” he said. There is a baby elephant. She is coming to us by the river.” I switched off the computer to save solar power and rushed to the doorway, where Patrick pointed to a small elephant trotting along the river’s edge toward camp. Her tiny trunk jiggled about as she rambled along the sand. Suddenly she changed directions, galloped into the long grass, and reappeared upstream jogging in yet another direction, looking wildly around. Finally she halted and lifted her trunk, turning the end around like a periscope.

Patrick, have you seen her mother any other elephants?” No, madame, she is very much alone in this place.” An orphan. The park was sprinkled with these tiny survivors, youngsters who had watched every adult in their family mowed down by poachers. From the air we had seen infants standing by their fallen mothers or wandering around in aimless search for their families. Some died right there, waiting for their mothers to rise again. Some never found the herd. By the time we arrived at the site, the young elephants were usually gone or dead. Now one youngster had stumbled onto the shore opposite our camp and stood still, trunk hanging low, looking away as if we did not exist.

I could see Harrison Simbeye and Jackson Kasokola, our other assistants, and Mark watching the small elephant from behind the marula trees at the workshop. She wandered around the beach again for a few more minutes, then disappeared into the thick acacia brush. Without speaking and alert for crocodiles, the men and I forded the shallow river. We stood in a long line staring at the lonely prints in the sand.

Elephants grow throughout their lives, so their age can be determined by measuring the length of their hind footprints. The size of the prints suggested that this elephant was five years old. We named her Gift, after the recently deceased daughter of Tom Kotela, one of the Zambian game scout leaders. But we doubted if we would ever see her again.

There are two species of elephants in Africa. One, Loxodonta cyclotis, is the forest elephant found in Congo. Most of the others, including those of the Luangwa Valley, are Loxodonta africana, the savanna elephant.

Normally, when there is little or no poaching, female elephants live in family units whose matriarchal gene lines persist for generations. As is the case with many other social mammals, a female remains in her birth group all her life, so the group is made up of grandmothers, mothers, aunts, and sisters who feed, play, and raise their young together until they die. Males born into the group remain with the family only until their hormones send them off in search of unrelated females with whom to mate. Then they wander on their own or with a loose alliance of cronies, taking risks, fighting, or showing off to attract as many females as possible. So there are no adult males permanently attached to the family unit.

Female elephants touch often, rub backs and shoulders, gently tangling trunks. From their mothers and older relatives, the youngsters learn which plants to eat, where the waterholes are, and how to avoid predators. When an infant squeals, any of the female group members will run to the rescue. An elephant family is a fortress of females.

But little Gift was alone. She was old enough to be weaned, yet how could she survive without her family unit? Elephants rarely adopt orphans, and never nonrelatives.

The next day we spotted Long Tail and Cheers across the river, tearing up long grass and shoving it into their mouths with their trunks. Gift was forty yards away, feeding on shorter, tenderer grasses. From then on, whenever Long Tail, Cheers, or the other males wandered into camp, little Gift bounced along behind them. She looked minute next to them, a windup toy circling on her own in the background. In the absence of her family unit, and abandoning all normal elephant behavior, Gift had taken up residency near the Camp Group males.

For the most part, the males ignored her. At five, she was much too young to breed and, as is true of most male mammals, they had no other use for her. Before poaching was rampant in the Luangwa Valley, female elephants usually ovulated for the first time at fourteen years of age and delivered their first calf at sixteen. So, as the males roamed around in their habitual feeding patterns, first on the hillsides, then across the river in the long grass, the diminutive Gift stayed within sight of them but fed on her own. Sometimes she stepped gingerly up to one of the towering males and reached out her tiny trunk in greeting. Her mother, sisters, and aunts would have snaked their trunks out to hers and twisted them together. Her female family would have circled her, bumped heads, rubbed backs like affectionate tanks. Gift would have observed older mothers suckling their young and played with other infants, all the while learning the elephant alphabet. But the Camp Group males turned away from her, their huge backsides blocking her only chance at companionship. A cold shoulder from an elephant is a big rejection.

It would be an exaggeration to call any female elephant dainty. With their tree-trunk legs, thick ankles, and heavy shoulders not to mention their less than elegant profiles it’s difficult to describe them as at all feminine. However, Gift came close to being ladylike, at least for an elephant. Perhaps it was just that compared to the males, she seemed so much more delicate in her feeding and lighter of foot. She had other little habits that reminded me of a young girl who had somehow found herself in a male world. One afternoon while feeding on a small tree, she broke off a branch covered with fresh, green leaves. Instead of eating the forage, she wandered around rather aimlessly for over thirty minutes carrying the branch in her trunk, as a girl might carry wildflowers in a spring meadow.

With no group, Gift had no playmates. More than a pastime, play with peers and elders is essential for forming lifelong bonds, perfecting trunk- eye coordination, and testing dominance. Gift had to play alone. Once she stepped into the flooded river and submerged herself completely. Rolling over and over, she splashed about, with a leg poking up here, her trunk there. Now and then she would burst out of the water like a breaching whale and dive underneath again.

Gift’s special trademark was her jig. We often blundered into her when we rushed around camp. In a hurry to get to the plane for an elephant survey or to the office for binoculars or notebook, we would stride around a tree and come face to face with her. But she never charged us. If we got too close for her liking, she would trot away about five steps, stop, lift her tail slowly to the side, throw her head around dramatically, make a one-eighty turn, and trot back toward us. She would repeat this several times, as if dancing a jig. She also performed her dance for the massive buffaloes who fed in our camp and sometimes got in her way. Gift was never a pet; we never fed her and certainly did not touch her. But she must have felt safe around us, because she lived nearby as though she had set up her own camp near ours. She sometimes stood near our cottages watching the small female families across the river, as the youngsters frolicked and the adults greeted one another with tangled trunks. We hoped that she would join them, that against all elephant tradition they would adopt her. But she never ventured near them. As she grew older, Gift wandered farther from camp during her feeding forays, and sometimes we would not see her for weeks, and then even for months. We always worried that she had been shot, and then she would show up at our camp again.

Whenever we flew over the valley, observing the elephant families from the air, taking notes on every detail of the groups, counting to see if their numbers were increasing, I always searched for Gift. I longed to see a little elephant among the others, one who would perhaps look up at us and dance her jig.

Copyright © 2006 by Mark Owens and Delia Owens. Reprinted with permission by Houghton Mifflin Company.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0395893100

- ISBN 13 9780395893104

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages230

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Elephants and People

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # Hafa_fresh_0395893100

Secrets of the Savanna: Twenty-Three Years in the African Wilderness Unraveling the Mysteries of Ele

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0395893100

SECRETS OF THE SAVANNA: TWENTY-T

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.95. Seller Inventory # Q-0395893100