Items related to The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History...

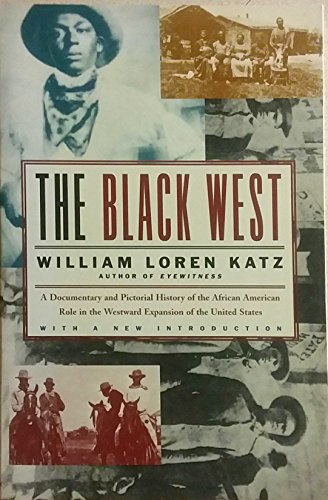

The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States - Softcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chapter 1

The Explorers

We Americans have learned about the development of the West from history books, school texts, novels, movies and TV screens. In so doing we have been silently saddled with the myth that the frontier cast of characters included only white and red men. Although western stereotypes abound-treacherous red men, hearty pioneers, intrepid explorers, gentle missionaries, heroic and handsome cowboys and cavalrymen -- black men and women do not appear.

In 1942 Pulitzer-prize historian James Truslow Adams, author and editor of more than two dozen volumes on American history, insisted that black men "were unfitted by nature from becoming founders of communities on the frontier as, let us say the Scotch Irish were preeminently fitted for it...." To be sure, black men had "many excellent qualities," Adams noted, "even temper, affection, great loyalty...imitativeness, willingness to follow a leader or master," but these were, one must agree, "not the qualities which...made good...frontiersmen...." The racial bias and misinformation upon which this statement was based has been traditional among American historians -- and has prolonged our ignorance.

Black men sailed with Columbus and accompanied many of the European explorers to the New World. Pedro Alonzo Nino, said to be black, was on Columbus's first voyage, and other Africans sailed with him on his second voyage the following year. By Columbus's third voyage in 1498 the black population of the New World was expanding, its economic value slowly being recognized by the Spanish and Portuguese.

The Spaniards saw the Africans as both useful and dangerous. In 1501 when a royal ordinance first gave official sanction to the importation of African slaves to Hispaniola, many feared to use them because of their rebelliousness. Two years later Governor Ovando of Hispaniola complained to King Ferdinand that his African slaves "fled among the Indians and taught them bad customs and never would be captured." His solution, however, based on labor needs, was to remove all restrictions on their importation. He evidently won his point at the Spanish court. On September 15, 1505, King Ferdinand wrote him: "I will send more Negro slaves on your request. I think there may be a hundred. At each time a trustworthy person will go with them who may share in the gold they may collect and may promise them ease if they work well." By 1537, the governor of Mexico noted, "I have written to Spain for black slaves because I consider them indispensable for the cultivation of the land and the increase of the royal revenue." Ten years earlier Antonio de Herrera, royal historian to King Philip II of Spain, estimated their New World colonies as having about ten thousand Africans. This was ninety-two years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth. By 1600, more than ninety thousand Africans had been sent to Latin America. The landings at Jamestown and Plymouth were still to come.

When the Spanish conquistadores left Hispaniola to explore the mainland of the Americas, black men accompanied them. In 1513 Balboa's men, including thirty Africans, hacked their way through the lush vegetation of Panama and reached the Pacific. There the party paused and built the first ships ever constructed on America's west coast. In 1519 Africans accompanied Cortez when he conquered the Aztecs; the three hundred Africans dragged his huge cannons. One of Cortez's black men then planted and remained to harvest the first wheat crop in the New World. Others were with Ponce de Leon in Florida and Pizarro in Peru, where they carried his murdered body to the cathedral.

Pioneer Maroon Settlements

From the misty dawn of America's earliest foreign landings, Africans who broke their chains fled to the wilderness to create their own "maroon" settlements (after a Spanish word for runaways). Europeans saw "maroons" as a knife poised at the heart of the slave system, perhaps pressed against the entire thin line of white military rule in the New World. But for the daring men and women who built these outlaw communities in the wilderness, they were a pioneer's promise.

In remote areas of the Americas beyond the reach of European armies many became strongly defended agricultural and trading centers bearing such names as "Disturb Me If You Dare" and "Try Me If You Be Men." Maroon songs resonate with defiance: "Black man rejoice/White man won't come here/And if he does/The Devil will take him off." For more than 90 years in 17th century Brazil the Republic of Palmares fought off onslaughts by Dutch and Portuguese troops. In 1719 a Brazilian colonist wrote to King Jao of Portugal of maroons: "Their self-respect grows because of the fear whites have of them."

Women played a vital role in these pioneer settlements. Often in short supply, they were sought as revered wives and mothers who would provide stability, the nourishment of family life and children, the community's future. Families meant these enclaves would strive for peace, but that their soldiers would fight invading slave-catching armies to the death.

Two women ruled maroon settlements in colonial Brazil. Fillipa Maria Aranha governed a colony in Amazonia where her military prowess convinced Portuguese officials it was wiser to negotiate than try to defeat her armies. A treaty granted Aranha's people independence, liberty and sovereignty. In Passanha, an unnamed African woman hurled her Malali Indian and African guerrilla troops against European soldiers.

Throughout the Americas Africans were welcomed into Native American villages as sisters and brothers. Often enslaved together, red people and black people commonly united to seek freedom. "The Indians escaped first and then, since they knew the forest, they came back and liberated the Africans," writes anthropologist Richard Price about the origins of the Saramaka people of Suriname in the 1680s. He is describing an American frontier tradition as old as Thanksgiving.

A Native American adoption system that had no racial barriers recruited black men and women in the battle against encroaching Europeans. Artist George Catlin described "Negro and North American Indian, mixed, of equal blood" as being "the finest built and most powerful men I have ever yet seen."

Before 1700 maroons were generally ruled by Africans, but after that they were more likely to be governed by children of African-Native American marriages. Carter G. Woodson, father of modern black history, called this racial mixture "one of the longest unwritten chapters in the history of the United States." In the 1920s research at Columbia University by anthropologist Melvin J. Herskovits proved that one in every three African-Americans had an Indian branch in their family tree.

Beginning with a Jamestown, Virginia battle in 1622 whites complained "the Indians murdered every white but saved the Negroes." Charleston's Colonel Stephen Bull urged division of the races in order to "Establish a hatred between Negroes and Indians." Europeans prevented their meetings and marriages, ended enslavement of Indians and introduced African slavery to the Five Civilized Nations, the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks and Seminoles. But John Bartram found Indian slavery was so gentle it permitted slaves to marry masters and find "freedom...and an equality."

"We make Indians and Negroes a checque upon each other lest by their Vastly Superior Numbers we should be crushed by one or the other," stated Reverend Richard Ludlam. Native Americans were hired or bribed to hunt slave runaways, and slaves were armed to fight Native Americans. When local nations refused, fighters from distant regions were hired.

But the white lid never closed shut. In 1721 the Governor of Virginia made the Five Nations promise to return all runaways; in 1726 the Governor of New York had the Iroquois Confederacy promise; in 1746 the Hurons promised and the next year the Delawares promised. None ever returned a slave.

To the consternation of slaveholders, two dark peoples began to unite as allies and family from the Atlantic westward.

Stephen Dorantes or Estevan

The first African whose name appears in the historical chronicles of the New World was an explorer of many skills, though he lived and died a slave. Estevan, born in Azamore, Morocco, at the turn of the fifteenth century, was the servant of Andres Dorantes and has variously been called Estevanico, Stephen Dorantes or Esteban. On June 17, 1527, in San Lucas de Barrameda, Spain, he and his master boarded a ship for the New World. Estevan was then about thirty and possibly no more than his master's manservant. Both were part of a five-hundred-man expedition to explore the northern shore of the Gulf of Mexico, an assignment authorized by King Charles I and headed by his newly commissioned governor of Florida, PŠnfilo de NarvŠez. In all probability Estevan was not the only African in the party; but he became the first to shape the course of history both for people living in the New World and European newcomers.

On April 14, 1528, the NarvŠez expedition landed in Florida, probably at Sarasota Bay, and began its planned exploration. Almost immediately it floundered on a combination of inept management and natural calamities and its numbers were steadily reduced through starvation, desertions and even cannibalism. In one Indian village, which they would later rename "Misfortune Island," through disease the party dwindled from eighty to fifteen. Finally only four were left, Estevan, his master and two other whites. All four were soon enslaved by Indian tribes. During a semiannual Indian gathering the four met and, like slaves anywhere, began plotting their escape. At the next Indian gathering the three white and one black slave escaped together, plunging westward along the Gulf Coast.

The only record of the years of wandering was later recorded by Alvar NķŮez Cabeza de Vaca, their leader. He told how the four managed to get along with Indian tribes by posing as medicine men, using the sign of the cross, Christian prayers and incantations, and some efforts at minor surgery. Estevan, Cabeza de Vaca noted, "was our go-between; he informed himself about the ways we wished to take, what towns there were, and the matters we desired to know." In 1536, eight years after the NarvŠez party had landed in Florida, its four sole survivors reached Spanish headquarters in Mexico.

The three white men left for Spain, Andres Dorantes selling Estevan to Antonio de Mendoza, viceroy of New Spain. Estevan's stories, embellished from Indian tales about Cibola or "The Seven Cities of Gold," enthralled his Spanish listeners, particularly when he produced some metal objects to demonstrate that smelting was an art known in Cibola.

In 1539 Governor Mendoza selected Father Marcos de Niza, an Italian priest, to lead an expedition to Cibola. Estevan was the logical choice for his guide. The African was sent ahead with several Indians and two huge greyhounds, and instructed to send back wooden crosses whose size would indicate his nearness to his goal. Estevan again decided to pose as a medicine man, this time carrying a large gourd decorated with strings of bells and a red and white feather. Soon many Indians were drawn to the party of this mysterious black man. And one by one huge white crosses began to arrive in Father Marcos's camp, carried by Estevan's Indian guides, who also reported that the African's entourage had swelled to three hundred and he was being showered with jewelry. There was also the evidence of the crosses: each was larger than the last, and every few days another arrived. Father Marcos issued orders to hasten the march to Estevan and Cibola.

Father de Niza Sends Estevan Ahead

So the sayde Stephan departed from mee on Passion-sunday after dinner: and within foure dayes after the messengers of Stephan returned unto me with a great Crosse as high as a man, and they brought me word from Stephan, that I should forthwith come away after him, for bee had found people which gave him information of a very mighty Province, and that he had sent me one of the said Indians. This Indian told me, that it was thirtie dayes journey from the Towne where Stephan was, unto the first Citie of the sayde Province, which is called Ceuola. Hee affirmed also that there are seven great Cities in this Province, all under one Lord, the houses whereof are made of Lyme and Stone, and are very great....

Father Marcos de Niza in Richard Hakluyt, Hakluyt's Collection of the Early Voyages, Travels, and Discoveries of the English Nation (London, 1810)

But no further word came from Estevan. Weeks later two wounded Indians arrived and told Father Marcos of Estevan's capture and the massacre of the entire expedition just as they were about to enter an Indian village. Their report concluded, "We could not see Stephen any more, and we think they have shot him to death, as they have done all the rest which went with him, so that none are escaped but we only."

Estevan's story does not end with his death. He was the first non-Indian to explore Arizona and New Mexico and the stories and legends of his journey stimulated the explorations of Coronado and de Soto.

The Death of Estevan

These wounded Indians I asked for Stephan, and they...sayd, that after they had put him into the...house without giving him meat or drinke all that day and all that night, they took from Stephan all the things which hee carried with him. The next day when the Sunne was a lance high, Stephan went out of the house [and suddenly saw a crowd of people coming at him from the city,] whom as soone as hee sawe he began to run away and we likewise, and foorthwith they shot at us and wounded us, and certain men fell dead upon us...and after this we could not see Stephan any more, and we thinke they have shot him to death, as they have done all the rest which went with him, so that none are escaped but we onely.

Father Marcos de Niza in Richard Hakluyt, Hakluyt's Collection of the Early Voyages, Travels, and Discoveries of the English Nation (London, 1810)

Estevan Becomes a Zuni Legend

It is to be believed that a long time ago, when roofs lay over the walls of Kyaki-me, then the Black Mexicans came from their abodes in Everlasting Summerland. Then the Indians of So-no-li set up a great howl, and thus they and our ancients did much ill to one another. Then and thus was killed by our ancients, right where the stone stands down by the arroyo of Kya-ki-me, one of the Black Mexicans, a large man, with chilli lips.

Cited by Monroe W. Work, The Negro Year Book, 1925

Estevan also lived on in a Zuni legend which told of a brave black man who had entered their village and had been slain. Though no one ever found the Seven Cities of Gold, the belief in their existence and the search for them not only led to exploration of the entire American Southwest, but gave the newcomers from abroad the material they would shape into the first great American folk myth. That an African slave should first search the New World for a mythical land of wealth and comfort is symbolic of the black experience in America.

Jean Ba...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTouchstone

- Publication date1996

- ISBN 10 0684814781

- ISBN 13 9780684814780

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0684814781

The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0684814781

The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0684814781

The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0684814781

The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History of the African American Role in the Westward Expansion of the United States

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0684814781

THE BLACK WEST: A DOCUMENTARY AN

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.05. Seller Inventory # Q-0684814781