Items related to The Perfect Summer

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Juliet Nicolson has written an elegiac and atmospheric account of England in the summer of 1911, three years before the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo and the beginning of World War I. The Perfect Summer is primarily a portrait of life among Britain's wealthiest and most privileged citizens, with occasional bows in the direction of those less fortunate and more aggrieved, but it doesn't take many pages before the reader is likely to start wondering, as I certainly did: What, exactly, was so "perfect" about that particular summer?

The narrative begins, "On the first day of May 1911 temperatures throughout England began to rise, and everyone agreed that the world was becoming exceedingly beautiful," and the reader immediately assumes that the weather henceforth will be, well, perfect. But though there were many lovely days in England that summer, there were also many dreadful ones. By early July "the oppressive weather was becoming increasingly hard to tolerate," and "on 17 July most of the country was perspiring in eighty-degree temperatures," which will seem balmy to anyone inured to a Washington summer but was uncomfortably hot in a country that did not enjoy the relief of air-conditioning and expected people to wear layers of elaborate clothing in all temperatures, including, for fashionable women, corsets. Not merely that, but "by 20 July there had been twenty consecutive days without rain," and "two days later fires began to break out spontaneously along the railway tracks at Ascot, Bagshot and Bracknell," and "in King's Lynn a temperature of 92ºF broke all previous records for that part of the country."

That was scarcely the end of it. "At the beginning of August the constitutional health of England was beginning to falter badly in the continuing heat," and "by late August lassitude had begun to further weaken the nation's energy, as the hot weather hung over England like a brocade curtain." Not until later in the month did the heat finally break, by which time many of those who could afford to do so had fled to the beach, though the cool water provided only limited relief to women, who wore bathing suits almost as heavy as their clothing and who were shepherded into the water inside a ridiculous contraption, a "fully enclosed bathing machine . . . a sort of garden shed with wheels at one end." Women filed into this pen, changed into their bathing costumes far from the prying eyes of men, and when all was ready, "a horse, a muscley man or even occasionally a mechanical pulley-contraption [dragged] the whole machine and its human contents to a line just beyond the surf."

Amusing? Absolutely. But "perfect"? Hardly. The hunch here is that Nicolson's publisher, remembering the remarkable success a decade ago of Sebastian Junger's The Perfect Storm, tried to roll the same dice. It's harmless enough, but it's something of a pity to watch Nicolson struggling to live up to her book's title when so much of the evidence points in a quite contrary direction. The story that Nicolson tells, and for the most part tells well, isn't just about dreadful weather, but about rising tensions between Britain and Germany, about bitter confrontations between labor and capital, about restlessness and anger among the rural and urban poor, about "the entire structure of the country teetering towards breakdown" under the weight of paralyzing strikes and bitter debate in Parliament over a measure (it passed on August 10) that greatly restricted the power of the House of Lords.

Yes, the summer did have its light moments. A year after the sudden death of the immensely popular Edward VII, George V was crowned amid all the usual pomp. Nicolson writes sympathetically about this quiet, undemonstrative man and his wife, May, who had to change her name to Mary after becoming queen. She was a shy, "self-conscious woman who now found herself at the pinnacle of a society that alarmed her." She "lived in a palace lit by two hundred thousand electric light bulbs, with a faithful husband, six loving children, dozens of servants, twelve personal postmen doing their rounds inside the palace, a private police force, and six florists. It felt like a trap." Nicolson is especially good about this sort of thing, no doubt in great measure because she knows whereof she writes: She is the granddaughter of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson, whose privileged but exceedingly complicated marriage was elegantly portrayed by her father, Nigel Nicolson, in his hugely successful book, Portrait of a Marriage (1973).

Nicolson writes about the doings of the upper crust with a not-unattractive mixture of fascination and amusement. She is perhaps a bit more fascinated than she really ought to be by lavish parties, extravagant menus and glittering gowns -- her accounts of "the gay summer life of the capital" become a trifle wearing after a while -- but she also can be wry and unexpectedly informative. Thus, for example, we have the trendy and beautiful Lady Diana Manners, spoiled within an inch of her life, forsaking the designs of the couturier Charles Frederick Worth:

"Diana . . . had her eye on the far more pacey clothes produced by his apprentice and successor Paul Poiret, the current French arbiter of fashion, who had established a considerable following with his sexy, clingy dresses. Curiously, Poiret was also the designer responsible for the inhibiting and controversial hobble skirt and, paradoxically but 'in the name of liberty', the man who 'proclaimed the fall of the corset and the adoption of the brassière.' The freedom he offered was eagerly welcomed behind locked bedroom doors, where time was often precious to illicit lovers. Poiret well knew that in an era of the elaborately laced corset, 'undressing a woman is an undertaking similar to the capture of a fortress.' "

There's much amusing stuff of that nature in The Perfect Summer, and a cast of interesting characters, some familiar, some not: Winston Churchill, "the youngest Home Secretary since Robert Peel nearly a hundred years earlier," "opportunistic," "flagrantly ambitious," "unpredictable, verging on reckless," "a man to be watched, with caution"; Ben Tillett, leader of the dockworkers' union, "an inspiration and hero to his union's quarter of a million members"; Rupert Brooke, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Stephen, Siegfried Sassoon and other young writers, poets and litterateurs who were getting ready to change English letters in dramatic, lasting ways.

There are lively accounts of aristocratic house parties where, after the lights went out, lovers crept about from room to room: "Lord Charles Beresford became particularly vigilant after leaping with an exultant 'Cock-a-doodle-doo!', onto a darkened bed, believing it to contain his lover, only to be vigorously batted away by the much startled Bishop of Chester." More seriously, there are vivid passages about the rural poor, afflicted by "disease and dissatisfaction," and their urban counterparts, living in fetid tenements where "four or five people might share not just one room but one bed, crammed into a twelve-foot by ten-foot space, a baby squashed in one corner, a banana crate for its cot."

Somehow one doubts that the summer of 1911 was "perfect" for these people, and somehow one suspects that this same doubt is shared by Nicolson herself. She seems to have set out to write a nostalgic book about England at the 10th or 11th hour before calamity, and to have encountered a great many inconvenient facts. It is to her credit that she does not shy away from recording them, but it's a pity that she didn't adjust her narrative's tone in order to accommodate them.

Copyright 2007, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherJohn Murray

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0719562422

- ISBN 13 9780719562426

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number3

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 5.98

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

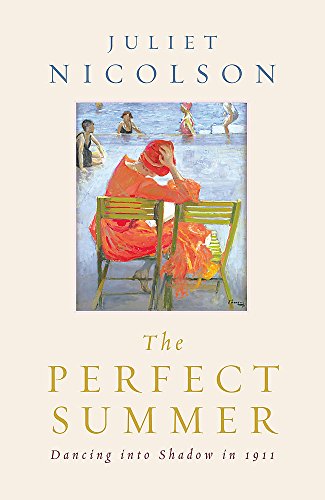

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Hardback. Condition: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # GOR001223418

The Perfect Summer : Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Condition: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 14414041-6

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Condition: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. . Seller Inventory # 7719-9780719562426

The Perfect Summer: Dancing Into Shadow: England in 1911

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.4. Seller Inventory # G0719562422I3N00

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Good. 1st Edition. Seller Inventory # ABE-1606244662592

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: very good. Later printing. 2nd impression. 8vo. Pp xiii + 290 + 16pp b&w plates. Black cloth boards stamped in gilt on the spine. A clean, unmarked and tightly bound copy in an unclipped dust jacket. Lightly bumped at the bottom corner of upper board. Light spotting to the book block edges and the prelims. Seller Inventory # 102146

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Used; Good. **SHIPPED FROM UK** We believe you will be completely satisfied with our quick and reliable service. All orders are dispatched as swiftly as possible! Buy with confidence! Greener Books. Seller Inventory # mon0000060953

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow in 1911

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Used; Good. ***Simply Brit*** Welcome to our online used book store, where affordability meets great quality. Dive into a world of captivating reads without breaking the bank. We take pride in offering a wide selection of used books, from classics to hidden gems, ensuring there is something for every literary palate. All orders are shipped within 24 hours and our lightning fast-delivery within 48 hours coupled with our prompt customer service ensures a smooth journey from ordering to delivery. Discover the joy of reading with us, your trusted source for affordable books that do not compromise on quality. Seller Inventory # mon0001726801

THE PERFECT SUMMER

Book Description Hardback. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. 9.1 X 6.3 X 1.3 inches; 256 pages. Seller Inventory # 143031

The Perfect Summer: Dancing into Shadow England in 1911

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Like New. Dust Jacket Condition: Like New. Third printing. Signed by the author with a dedication to a previous owner on the title page. A lovely copy in like new condition in a like new dust jacket. By Author. Seller Inventory # 017000657