Items related to Kickboxing Geishas: How Modern Japanese Women Are Changing...

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

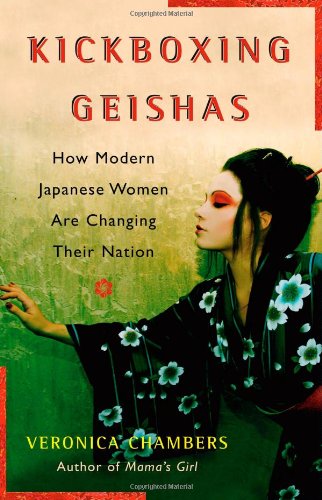

KICKBOXING GEISHAS

The funny thing about my love affair with Japan is that it was never the country of my dreams. The country I loved, the bad boy I could never get to walk me down the aisle, was France. Two days into my first trip to Paris, I called my mother from a pay phone on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. "Sell everything I own," I said dramatically, "I'm staying." Even as the words came out of my mouth I knew they were untrue. I was twenty-four years old. I worked for the New York Times at a job that journalists twice my age would kill for. All that, and I didn't own much worth selling. I had just enough money to cover the cost of my trip and I was too pragmatic to play the starving artist. But the sentiment, the desire to stay, said everything I could not about how deeply I had fallen in love with the city, how I longed to follow in the footsteps of all the writers who had made Paris their home before me.

I spent the next five years trying to get to Paris, watching French movies, reading French Elle, studying French, visiting whenever I could. I was twenty-nine and working at Newsweek magazine when a colleague named Greg Beals suggested I apply for a fellowship to go to Japan. "But I'm not trying to go to Japan," I told him. "I want to go to Paris." He rolled his eyes. Anyone who had spent any amount of time with me knew that I was gunning for Newsweek's Paris bureau. "Yeah, well, they're not giving out fellowships to go to Paris," he says. "You should apply for this fellowship, check out Tokyo."

I had visited my friend Mina in Shanghai just a few months before. I remember overhearing a lengthy discussion among foreign correspondents at a bar in New York about the difference between those who go to China and those who go to Japan. China folks were serious. People who went to Japan, said the journalists I was with, only filed superficial stories about music and fashion. They said this as if it were a bad thing, but it piqued my interest nonetheless. I liked music and fashion. I adored the writer Banana Yoshimoto, author of Kitchen, and her warm, frothy tales of young women coming of age in Tokyo. I took the application from Greg and promptly forgot it.

God bless Greg Beals. Two months later, he came by my office. "Did you apply for that fellowship?" I shook my head no, dug it out from the "Don't Forget" pile on my desk and was sad to see that I'd missed the deadline. "Maybe next year?" I said weakly. An hour later, Greg was back. "You're in luck," he said. "I called over there and they've extended the deadline."

In Tokyo I stayed at International House, or I-House, a kind of Harvard Club for Western writers and academics in the Roppongi section of the city. Roppongi is known for its high-density population of foreigners, nightclubs, and restaurants. Later, I would look down on Roppongi as a gaijin ghetto, gaijin being the Japanese word for foreigners. But for me, it was a good starting place: filled with clubs and restaurants and a lively street life that kept me from feeling completely isolated.

I grew up in New York City, so I knew a thing or two about crowds. But in Tokyo, density is the thing. Tokyo is the most heavily populated city in the world: more than a quarter of the nation's population live crammed into an area that represents less than 2 percent of the country. It's got a good ten million people on Mexico City, Sao Paolo, or New York. So the second most important phrase I learned was "sumimasen," a hybrid of "excuse me" and "I'm sorry." It is the oil that keeps the wheels of social grace turning. You say sumimasen when you bump into someone on the train or when you want them to know that if they don't move, you will bump into them. Sumimasen is used when you want to catch the attention of a friend, colleague, or stranger, or when you want to ask a question, the time, directions, anything.

But it is also a kind of thank you. A way to say, "I'm sorry that I've taken up some of your precious time. I so appreciate it." The first time I took a rush hour train and watched a white gloved official literally shove us into the subway car, I realized that sumimasen was the vocabulary equivalent of those white gloves. In a city of twelve million people, you are bound to step on some toes. But sumimasen smoothes it out.

In one of my favorite poems, Yusef Komunyakaa writes about a black man's sense of isolation and humiliation in the American South. The poem is called I Apologize For the Eyes in My Head. In Japan, I apologized constantly, but it did not make me feel ashamed or isolated. Sumimasen was the thread that wove me closer to the fabric of Tokyo.

It was five years before Sofia Coppola's soporific tale of a young woman in Japan, but I soon began to live out my own Lost in Translation scenario. I had studied Japanese for six months before my trip. I did not yet dream in Japanese, but occasionally, I daydreamed in the language: a kind of Romper Room fantasy where various brightly colored objects would be pointed out to me and I would, correctly, call them by their Japanese name. When I arrived in Tokyo, I was immediately set up with a series of translators. I asked if the translators could take a back seat, filling in where necessary. "Well..." my fellowship adviser said, "we'll see." As any visitor to Japan and I suspect many other Asian countries soon learns, you are rarely told a straight-out "No." Instead, your host oh so politely sidesteps a yes.

During meetings when I greeted the interviewee with a simple "Ohayo gozaimasu," there would be much exclamation about how wonderful my Japanese was. If I introduced myself and said where I was from, there would be more amusement and praise. Once I started to ask a question in Japanese, however, my interpreters firmly stepped in. Later, they would tell me that I could speak a little Japanese, but they were there to make the interviewee feel at ease. It was important to a Japanese artist or executive that he or she not be misquoted or misunderstood.

There were more dangers in my trying to express myself in Japanese. If I spoke more Japanese than my counterpart spoke English, this would cause them to lose face. Losing face being of course, the utmost dishonor. Finally, my translator explained, I was a representative of the United States and the Japan Society, who had been kind enough to give me this fellowship. Did I want to risk repercussions to fall down upon my country and future fellows should I make some sort of careless mistake? This confirmed the comical Lost in Translation scenes that anyone who has worked with an interpreter has experienced. You ask a question to a dignitary, say, the mayor of Yokohama. Your interpreter asks the question in Japanese. The mayor gives a long, elaborate answer in Japanese. There is much gesturing and emotion and nuance. You don't need to understand the words to know this: you can see it, you can feel it. Then your interpreter turns to you and says "He says yes." The interpreters are always filtering and yet it is so easy to put yourself in their hands.

There were two main interpreters I worked with. One I secretly called "Mama-san." She was a fifty-something woman whose only child had gone off to college and who had recently reentered the work force. I called her "Mama-san" because she was a Japanese Doris Day: prim and proper, always in skirts and sensible shoes, a frilly pink umbrella by her side, in case it should rain. She showed up early for every appointment and dragged me, like a child, down the streets of Tokyo at lightning bolt speed. She told me what I should or shouldn't do and what I should or shouldn't say.

It was March when I arrived, and colder than I had expected. Sex and the City was the hit show back at home and following Carrie Bradshaw's stylistic lead, I had stopped wearing stockings. This did not escape Mama-san's notice.

"You aren't wearing stockings," she pointed out.

I muttered something in a twelve-year-old's voice about this being the style.

She sighed, "Maybe no one will notice."

I was stockingless again the next time she saw me. "Your legs must be very cold," she said.

I was, in fact, freezing and I had tried to remedy the situation. "I went to the store, but they didn't have any stockings in my size."

She could hardly argue with this. Japanese women are universally tiny. I am universally not. She clucked, "Maybe no one will notice."

I-House was located on a side street of Roppongi, at the high point of a small hill. If you went down the hill, you found the streets and clubs along the wide street Roppongi-dori. It was great for people watching: men in shiny suits pressing strip club flyers into the reluctant hands of passersby; young club girls teetering around in high heels while looking for foreign boyfriends; salarymen -- the Japanese equivalent of the man in the grey flannel suit -- working women, students, and lots of foreigners from all over the world. At that time, spring 2000, schoolgirls, the joshi kosei, were all the rage. It was not uncommon on a Sunday afternoon to pass one group of girls dressed up like the court of Marie Antoinette, walk one block down and see another group of girls dressed like Hello Kitty and then turn the corner and bump into a bunch of leather-clad biker chicks. It wasn't so much that these girls pioneered one particular style, as it was that they were fearless and relentless in their ability to cycle through every period in fashion history. These Japanese had long been the master of a certain kind of copycat culture. But the teenage girls, who took care of every detail -- from the right period shoe, to a three-hour makeup job to get the punk rock look just right -- took the copycatting to another level. This was a case of "Anything you can do, I can do better."

The obsession with teenage girls was not relegated to street culture. For a retrospective of his work at the Tokyo Contemporary Museum of Art, seminal designer Issey Miyake invited over one hundred cheerleaders...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0743271564

- ISBN 13 9780743271561

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Kickboxing Geishas: How Modern Japanese Women Are Changing Their Nation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0743271564

Kickboxing Geishas: How Modern Japanese Women Are Changing Their Nation

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0743271564

KICKBOXING GEISHAS: HOW MODERN J

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.85. Seller Inventory # Q-0743271564