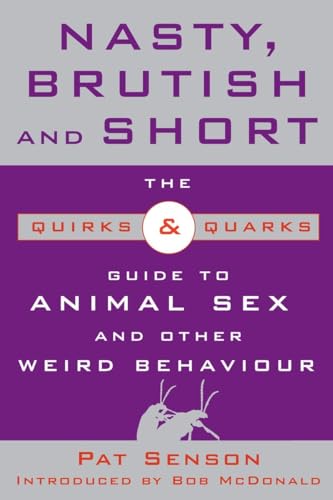

Items related to Nasty, Brutish, and Short: The Quirks and Quarks Guide...

Nasty, Brutish, and Short: The Quirks and Quarks Guide to Animal Sex and Other Weird Behaviour - Softcover

Birds do it, and bees do it, so do all animals, some of them in weird and wonderful ways. Quirks & Quarks' latest book explores the more bizarre behaviours of more than 100 creatures, from barnacles to Panda bears.

The tiny spider that has to tear off one of its two huge sex organs just to be able to get around; the sea slug that produces a powerful love drug and mates with both males and females; the bedbug that stabs its penis into the female's abdomen — the range of animal sexual practices is mind-boggling. And it's not only reproduction that has them doing very strange things. There's a beetle that shoots a stream of boiling hot, toxic liquid when it's threatened; a lizard that can run on water; a shrimp that explodes its prey.

Quirks & Quarks' latest guide is much more than a catalogue of peculiar practices, it's an engrossing look at the astonishing behaviours different animals have evolved in order to survive and reproduce.

With an introduction by Bob McDonald, host of Quirks & Quarks.

The tiny spider that has to tear off one of its two huge sex organs just to be able to get around; the sea slug that produces a powerful love drug and mates with both males and females; the bedbug that stabs its penis into the female's abdomen — the range of animal sexual practices is mind-boggling. And it's not only reproduction that has them doing very strange things. There's a beetle that shoots a stream of boiling hot, toxic liquid when it's threatened; a lizard that can run on water; a shrimp that explodes its prey.

Quirks & Quarks' latest guide is much more than a catalogue of peculiar practices, it's an engrossing look at the astonishing behaviours different animals have evolved in order to survive and reproduce.

With an introduction by Bob McDonald, host of Quirks & Quarks.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

For nine seasons biologist PAT SENSON was a producer with CBC Radio's national science program, Quirks & Quarks, where his documentary work received numerous awards and accolades. He can still be heard every week on CBC Radio across the country as he supplies science stories to the local afternoon shows through CBC's syndication service. Pat currently lives in Toronto with his partner and their two slightly addled cats.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

1

The Battle of the Sexes

The Insects

For examples of extreme sexual conflict in the animal world, insects are the place to look. From arms races to fatal copulation, they do it all.

Insect Arms Race

It would hardly be novel to say that males and females frequently want different things. But when it comes to insects, we’re not talking about hanging out with buddies at a football game versus staying home watching romantic movies. No, this is a story about sex, and so it’s ultimately about evolution, with males wanting one evolutionary outcome and females another. Nature has set up some species for sexual conflict that goes far beyond the battle over who takes out the garbage. Take, for example, the water strider. This group of insects is locked in a sexual struggle that has all the features of an evolutionary arms race, complete with occasional detente and the threat of mutually assured destruction.

You would probably recognize water striders if you saw them. They’re found all over the world, and according to Dr. Locke Rowe, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Toronto, just about anywhere there’s a pool of water there will be water striders. As their name suggests, they’re able to walk across the surface of the water, standing on the ends of their long legs.

Their sexual conflict arises out of the different desires of the males and females. The males want as many matings as possible. The more they mate, the more babies are their kin, and the more genes they’ll pass on. For the females, though, mating is much more costly, since it takes a lot of energy to produce eggs. As soon as a female’s eggs are fertilized, she doesn’t need to mate again, but the males are still going to show interest. Also, as Dr. Rowe says, “The females actually carry the males during mating, and that’s an energetic cost. So they fight. If you see water striders on the surface and look closely, you’ll see, after some time, males jumping on females and females struggling and somersaulting to get rid of them.”

So, the females have come up with ways to try and keep the males off their backs once they have already mated. In some species they have developed long spines that make it difficult for the males to climb on them. The males have fought back by evolving their entire body into one big grappling device. Each of their three pairs of legs has grappling hooks and spines that allow them to hang on, for dear life, to the females. In one species, the males have evolved antennae that are, Dr. Rowe says, “big, muscularized, swollen-up armaments that they use for grasping those females.” These antennae are not much use for sensing the environment any more (their original purpose) – but very helpful when the female doesn’t want to co-operate.

This back-and-forth retaliation has been going on throughout the water striders’ evolution. The females develop a way of repelling males, and the males come up with a way of countering the new apparatus. Then the female comes up with a new defence, and the male responds. And so on. Except, not always. Dr. Rowe has observed that sometimes there’s a de-escalation in the arms race, and there are fewer and fewer armaments on successive generations of the insects. Depending on the particular species, the arms race seems to be raging, quieting down, or staying steady. Curiously, as long as there’s a balance between the two sexes’ armaments, all these different species are about equally successful at reproducing. That’s a lot like a human arms race. As long as everyone’s in the same boat, then how well armed you are isn’t the point; it’s the balance that counts.

Sometimes the balance is off, and whenever the male has the advantage, mating rates shoot up to as much as ten times what they are in other strider species. But that puts females under a great deal of pressure to evolve defences, so it isn’t long before they do and balance is restored. This explains how escalation can happen, but why there’s de-escalation is more complicated.

No one knows for sure, but Dr. Rowe thinks it’s because of the heavy costs of the arms race to the individual insects. Their armaments take a lot of energy to grow and maintain and can get in the way of normal activity. So, if they are not needed, might as well get rid of them. De-escalation happens when females are so far behind the males in the arms race that they just give up. Then the males don’t need to be so heavily armoured, and the ones who waste less energy building grappling hooks have the advantage, and so gradually both sexes scale back. Same thing when males are scarce; then the females’ desire to breed leads them over a few generations to abandon their weapons and be nice to the guys.

But whether it’s a full-scale war or just a skirmish, as long as the armaments on both sides are balanced, then this arms race helps the species keep striding along.

Weevil Penises

It’s pretty safe to say that men and women generally have different priorities when it comes to sex. But that isn’t just a human trait. Throughout the animal kingdom, what females want is not always matched by male desire. A good example is the humble bean weevil (Callosobruchus maculatus), an animal that seems to have taken the battle of the sexes to a new extreme. Their copulatory conflict was first described by Dr. Helen Crudgington, a researcher at the University of Sheffield in England.

Looking for sexual activity among bean weevils is no simple task. The beetles are a common pest species found throughout the world, but they’re really small, only about three and a half millimetres long (about an eighth of an inch). And they’re fairly nondescript brown bugs, or they appear to be until you look at the males really closely. Examine the penis of a bean weevil and you’ll discover it’s covered in hard, sharp spines. The purpose of these spines? Well, when a male bean weevil mates, these spines puncture the lining of the female’s genital tract.

This is not, to say the least, what a female is looking for in a sexual encounter. So, she’s faced with a problem. She does need to get fertilized. After all, as Dr. Crudgington explains it, “It may not be in the interests of females to go along with those matings, but they obviously need at least one to get sperm to fertilize their eggs. And in evolutionary terms, it’s no good if you remain a virgin.” But the damage caused by the males, says Dr. Crudgington, “can produce costs for the female in terms of dehydration – that is, losing moisture from these wounds. And they can also be costly in the sense that they can be a route for the entrance of harmful pathogenic organisms. So, obviously, this is not ideal for the females.” Now there’s an understatement.

From the male perspective, however, there are two possible advantages to damaging the female like this. First of all, if she is injured, she’s unlikely to try to mate again until she’s healed. In the meantime, her eggs will mature, and the male who has fertilized her gets to be the father of all the offspring. Second, these wounds are so traumatic that they can leave the female close to death, and the biological response to that is to produce a lot of eggs quickly. It could be her last chance to have offspring, so, from an evolutionary perspective, she wants to have as many as possible, as soon as possible. And the male who got to her first is the one whose sperm she’s going to use when she lays those eggs. But it’s not in the male’s best interests to do too much damage to the female. Killing her is no good – she won’t produce any offspring that way, and he’ll have wasted all that energy chasing her down. For the male bean weevil, there has to be some level of restraint.

So we end up with a system that requires a certain balance. The male wants to mate with, but not damage too much, as many females as possible. The females want to mate with as few males as they can. How this manifests is quite curious. It’s what got Dr. Crudgington to look at the bean weevil’s sexual practices in the first place. She had noticed that, during mating, the females furiously kick at the males to get them off their backs. This “mate kicking,” as Dr. Crudgington calls it, is quite awkward, since the spines on the penis are lodged inside the females. But it seems to work. The females minimize their injuries, the males unload their sperm, and the species is thriving.

There’s an evolutionary lesson in all this, though. It doesn’t seem to make evolutionary sense for a species if sex is this dangerous for the individuals involved. It can only reduce the number of potential offspring. But evolution doesn’t work at the level of species. It’s the pressure on the individual to do the best he or she can for himself or herself that results in evolutionary change. And these spiny penises are great for the males, so they’ve stuck around (so to speak).

The Power of One

Some stories are not for the squeamish, and this one might leave you on edge. So, take a deep breath before you read on.

There’s a spider, Tidarren sisyphoides, that has an unusual sexual habit. While getting ready to find a female and mate, the male rips off one of his two sex organs and casts it aside. Then, unencumbered by the weight of the organ, he heads off in pursuit of a paramour. This seems like an odd and extremely painful measure, but Dr. Duncan Irschick, now a behavioural ecologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, thinks he knows why self-mutilation is this spider’s best strategy.

The answer comes from the evolutionary history of this critter. As is the case with many species of spider, the female T. sisyphoides is much larger than the male. In fact, in this species, the difference is huge: the female is one hundred times larger. And, not to put too fine a point on it, her sex organs are proportional to her body size. That’s a real problem for the male. If he’s one hundred times smaller than his mate, and his sex organs – or pedipalps, as they’re called – are proportional to his body, he’s never going to match up with his partner. What’s he to do? The answer is to develop really big pedipalps.

Calling them “really big” is an understatement. The two pedipalps each make up about 10 per cent of the spider’s total body mass. Dr. Irschick describes them as “giant beach balls sitting in front of the male.” They are big enough to fertilize the female, but they come at a cost for the males. They’re so large that when the male starts to walk or run, they drag along.

The male spiders want to find the females as quickly as possible. After all, as Dr. Irschick says, “Whichever male in this species finds the female first gets all the goodies.” If you want to speed yourself up, as any car enthusiast knows, one way is to reduce drag. So, these male spiders spin a silk thread (they are spiders, after all), wrap it around one of their pedipalps, tighten the thread to seal it off, suck out the fluid, and, well, rip off the unnecessary organ. Don’t try this at home! Also, as Dr. Irschick discovered, humans shouldn’t do this to the spider – he won’t survive. But when the male performs the surgery on himself, he’s able to head off quickly in search of a mate.

Removing this organ makes a major difference. In Dr. Irschick’s lab (he was working at Tulane University at the time), the researchers chased spiders, some with one and some with two pedipalps, around a track, to see how long they’d last. On average, the “intact” males pooped out after sixteen minutes, while the single-sided spiders lasted for as long as twenty-eight. Putting it in human terms, Dr. Irschick says, “That’s the equivalent of you going out and running about 2 miles [3.2 kilometres] versus ripping off your reproductive organ, or leg or some appendage, and then going out and running 3.5 miles [5.6 kilometres]. It’s a big performance advantage.”

The males definitely need this advantage. Female spiders of this species are few and far between in the forests of the southern United States, where they live. So males have a real challenge finding them. Any benefit in speed that they can get for their hunt is going to be critical. Of course, this advantage might come at a cost, too. It’s possible that losing one pedipalp cuts down on the amount of sperm the male can produce. But as far as anyone can tell, the males seem to be doing all right so far – the species’ population isn’t in any trouble. And while it might be painful for the spiders, until someone comes up with a way to conduct spider questionnaires, we’ll never know for sure whether it is.

If you think that the male has already sacrificed enough for the sake of sex, think again. For the male of this spider species, mating is basically a suicide mission. After he finds a female, they copulate and he stays attached to her body, which probably blocks access for other males. Eventually he dies, at which point, Dr. Irschick says, “He basically gets sucked dry [by the female] and flicked off like a piece of dirt, afterwards.” This is not exactly a great future for a young male spider to look forward to, but at least his genes are transferred to the next generation.

There’s one question that remains in this tale of self-sacrifice. Wouldn’t it be much easier for the male to evolve a larger body, to mate more easily with the female and keep his organs from dragging? The problem is, the bigger the individual male, the more energy he needs to expend finding a female. So, in fact, being small is an evolutionary advantage to these males. For the females, however, bigger is better, since the larger she is, the more eggs she can produce. So, the organ removal by the males seems to be a compromise solution. The alternative of evolving a single pedipalp is probably too difficult, because biology prefers symmetry. And ripping one off is a quick, easy operation, and it gets the job done.

But it does make you wonder: what possessed the first male spider to try tearing off a part of himself?

Bedbug Penis Tasting

Bedbugs are not a particularly romantic lot. For the males, sex is wham, bam, thank you ma’am. The females, on the other hand, are a deceptive bunch, each trying to appear chaste, even virginal, in their attempt to attract the male with the most sperm. But male bedbugs have their own means of testing a lady’s virtue. They’ve developed a phallus that can detect whether a female they’ve mated with has been faithful. Dr. Michael Siva-Jothy, an evolutionary physiologist at the University of Sheffield in England, thinks that this is an adaptation that prevents the males from wasting sperm.

Before we get to the perceptive penis, here are some other interesting facts about bedbug sex that are worth knowing. First, even though the females have a fully developed reproductive tract, the males don’t use it. It’s strictly for laying eggs. Dr. Siva-Jothy explains this oddity: “The male’s penis is like a hypodermic needle. He stabs it into the body wall of the female, and he inseminates directly into her body cavity. Now, that’s pretty strange.” Pretty strange, indee...

The Battle of the Sexes

The Insects

For examples of extreme sexual conflict in the animal world, insects are the place to look. From arms races to fatal copulation, they do it all.

Insect Arms Race

It would hardly be novel to say that males and females frequently want different things. But when it comes to insects, we’re not talking about hanging out with buddies at a football game versus staying home watching romantic movies. No, this is a story about sex, and so it’s ultimately about evolution, with males wanting one evolutionary outcome and females another. Nature has set up some species for sexual conflict that goes far beyond the battle over who takes out the garbage. Take, for example, the water strider. This group of insects is locked in a sexual struggle that has all the features of an evolutionary arms race, complete with occasional detente and the threat of mutually assured destruction.

You would probably recognize water striders if you saw them. They’re found all over the world, and according to Dr. Locke Rowe, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Toronto, just about anywhere there’s a pool of water there will be water striders. As their name suggests, they’re able to walk across the surface of the water, standing on the ends of their long legs.

Their sexual conflict arises out of the different desires of the males and females. The males want as many matings as possible. The more they mate, the more babies are their kin, and the more genes they’ll pass on. For the females, though, mating is much more costly, since it takes a lot of energy to produce eggs. As soon as a female’s eggs are fertilized, she doesn’t need to mate again, but the males are still going to show interest. Also, as Dr. Rowe says, “The females actually carry the males during mating, and that’s an energetic cost. So they fight. If you see water striders on the surface and look closely, you’ll see, after some time, males jumping on females and females struggling and somersaulting to get rid of them.”

So, the females have come up with ways to try and keep the males off their backs once they have already mated. In some species they have developed long spines that make it difficult for the males to climb on them. The males have fought back by evolving their entire body into one big grappling device. Each of their three pairs of legs has grappling hooks and spines that allow them to hang on, for dear life, to the females. In one species, the males have evolved antennae that are, Dr. Rowe says, “big, muscularized, swollen-up armaments that they use for grasping those females.” These antennae are not much use for sensing the environment any more (their original purpose) – but very helpful when the female doesn’t want to co-operate.

This back-and-forth retaliation has been going on throughout the water striders’ evolution. The females develop a way of repelling males, and the males come up with a way of countering the new apparatus. Then the female comes up with a new defence, and the male responds. And so on. Except, not always. Dr. Rowe has observed that sometimes there’s a de-escalation in the arms race, and there are fewer and fewer armaments on successive generations of the insects. Depending on the particular species, the arms race seems to be raging, quieting down, or staying steady. Curiously, as long as there’s a balance between the two sexes’ armaments, all these different species are about equally successful at reproducing. That’s a lot like a human arms race. As long as everyone’s in the same boat, then how well armed you are isn’t the point; it’s the balance that counts.

Sometimes the balance is off, and whenever the male has the advantage, mating rates shoot up to as much as ten times what they are in other strider species. But that puts females under a great deal of pressure to evolve defences, so it isn’t long before they do and balance is restored. This explains how escalation can happen, but why there’s de-escalation is more complicated.

No one knows for sure, but Dr. Rowe thinks it’s because of the heavy costs of the arms race to the individual insects. Their armaments take a lot of energy to grow and maintain and can get in the way of normal activity. So, if they are not needed, might as well get rid of them. De-escalation happens when females are so far behind the males in the arms race that they just give up. Then the males don’t need to be so heavily armoured, and the ones who waste less energy building grappling hooks have the advantage, and so gradually both sexes scale back. Same thing when males are scarce; then the females’ desire to breed leads them over a few generations to abandon their weapons and be nice to the guys.

But whether it’s a full-scale war or just a skirmish, as long as the armaments on both sides are balanced, then this arms race helps the species keep striding along.

Weevil Penises

It’s pretty safe to say that men and women generally have different priorities when it comes to sex. But that isn’t just a human trait. Throughout the animal kingdom, what females want is not always matched by male desire. A good example is the humble bean weevil (Callosobruchus maculatus), an animal that seems to have taken the battle of the sexes to a new extreme. Their copulatory conflict was first described by Dr. Helen Crudgington, a researcher at the University of Sheffield in England.

Looking for sexual activity among bean weevils is no simple task. The beetles are a common pest species found throughout the world, but they’re really small, only about three and a half millimetres long (about an eighth of an inch). And they’re fairly nondescript brown bugs, or they appear to be until you look at the males really closely. Examine the penis of a bean weevil and you’ll discover it’s covered in hard, sharp spines. The purpose of these spines? Well, when a male bean weevil mates, these spines puncture the lining of the female’s genital tract.

This is not, to say the least, what a female is looking for in a sexual encounter. So, she’s faced with a problem. She does need to get fertilized. After all, as Dr. Crudgington explains it, “It may not be in the interests of females to go along with those matings, but they obviously need at least one to get sperm to fertilize their eggs. And in evolutionary terms, it’s no good if you remain a virgin.” But the damage caused by the males, says Dr. Crudgington, “can produce costs for the female in terms of dehydration – that is, losing moisture from these wounds. And they can also be costly in the sense that they can be a route for the entrance of harmful pathogenic organisms. So, obviously, this is not ideal for the females.” Now there’s an understatement.

From the male perspective, however, there are two possible advantages to damaging the female like this. First of all, if she is injured, she’s unlikely to try to mate again until she’s healed. In the meantime, her eggs will mature, and the male who has fertilized her gets to be the father of all the offspring. Second, these wounds are so traumatic that they can leave the female close to death, and the biological response to that is to produce a lot of eggs quickly. It could be her last chance to have offspring, so, from an evolutionary perspective, she wants to have as many as possible, as soon as possible. And the male who got to her first is the one whose sperm she’s going to use when she lays those eggs. But it’s not in the male’s best interests to do too much damage to the female. Killing her is no good – she won’t produce any offspring that way, and he’ll have wasted all that energy chasing her down. For the male bean weevil, there has to be some level of restraint.

So we end up with a system that requires a certain balance. The male wants to mate with, but not damage too much, as many females as possible. The females want to mate with as few males as they can. How this manifests is quite curious. It’s what got Dr. Crudgington to look at the bean weevil’s sexual practices in the first place. She had noticed that, during mating, the females furiously kick at the males to get them off their backs. This “mate kicking,” as Dr. Crudgington calls it, is quite awkward, since the spines on the penis are lodged inside the females. But it seems to work. The females minimize their injuries, the males unload their sperm, and the species is thriving.

There’s an evolutionary lesson in all this, though. It doesn’t seem to make evolutionary sense for a species if sex is this dangerous for the individuals involved. It can only reduce the number of potential offspring. But evolution doesn’t work at the level of species. It’s the pressure on the individual to do the best he or she can for himself or herself that results in evolutionary change. And these spiny penises are great for the males, so they’ve stuck around (so to speak).

The Power of One

Some stories are not for the squeamish, and this one might leave you on edge. So, take a deep breath before you read on.

There’s a spider, Tidarren sisyphoides, that has an unusual sexual habit. While getting ready to find a female and mate, the male rips off one of his two sex organs and casts it aside. Then, unencumbered by the weight of the organ, he heads off in pursuit of a paramour. This seems like an odd and extremely painful measure, but Dr. Duncan Irschick, now a behavioural ecologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, thinks he knows why self-mutilation is this spider’s best strategy.

The answer comes from the evolutionary history of this critter. As is the case with many species of spider, the female T. sisyphoides is much larger than the male. In fact, in this species, the difference is huge: the female is one hundred times larger. And, not to put too fine a point on it, her sex organs are proportional to her body size. That’s a real problem for the male. If he’s one hundred times smaller than his mate, and his sex organs – or pedipalps, as they’re called – are proportional to his body, he’s never going to match up with his partner. What’s he to do? The answer is to develop really big pedipalps.

Calling them “really big” is an understatement. The two pedipalps each make up about 10 per cent of the spider’s total body mass. Dr. Irschick describes them as “giant beach balls sitting in front of the male.” They are big enough to fertilize the female, but they come at a cost for the males. They’re so large that when the male starts to walk or run, they drag along.

The male spiders want to find the females as quickly as possible. After all, as Dr. Irschick says, “Whichever male in this species finds the female first gets all the goodies.” If you want to speed yourself up, as any car enthusiast knows, one way is to reduce drag. So, these male spiders spin a silk thread (they are spiders, after all), wrap it around one of their pedipalps, tighten the thread to seal it off, suck out the fluid, and, well, rip off the unnecessary organ. Don’t try this at home! Also, as Dr. Irschick discovered, humans shouldn’t do this to the spider – he won’t survive. But when the male performs the surgery on himself, he’s able to head off quickly in search of a mate.

Removing this organ makes a major difference. In Dr. Irschick’s lab (he was working at Tulane University at the time), the researchers chased spiders, some with one and some with two pedipalps, around a track, to see how long they’d last. On average, the “intact” males pooped out after sixteen minutes, while the single-sided spiders lasted for as long as twenty-eight. Putting it in human terms, Dr. Irschick says, “That’s the equivalent of you going out and running about 2 miles [3.2 kilometres] versus ripping off your reproductive organ, or leg or some appendage, and then going out and running 3.5 miles [5.6 kilometres]. It’s a big performance advantage.”

The males definitely need this advantage. Female spiders of this species are few and far between in the forests of the southern United States, where they live. So males have a real challenge finding them. Any benefit in speed that they can get for their hunt is going to be critical. Of course, this advantage might come at a cost, too. It’s possible that losing one pedipalp cuts down on the amount of sperm the male can produce. But as far as anyone can tell, the males seem to be doing all right so far – the species’ population isn’t in any trouble. And while it might be painful for the spiders, until someone comes up with a way to conduct spider questionnaires, we’ll never know for sure whether it is.

If you think that the male has already sacrificed enough for the sake of sex, think again. For the male of this spider species, mating is basically a suicide mission. After he finds a female, they copulate and he stays attached to her body, which probably blocks access for other males. Eventually he dies, at which point, Dr. Irschick says, “He basically gets sucked dry [by the female] and flicked off like a piece of dirt, afterwards.” This is not exactly a great future for a young male spider to look forward to, but at least his genes are transferred to the next generation.

There’s one question that remains in this tale of self-sacrifice. Wouldn’t it be much easier for the male to evolve a larger body, to mate more easily with the female and keep his organs from dragging? The problem is, the bigger the individual male, the more energy he needs to expend finding a female. So, in fact, being small is an evolutionary advantage to these males. For the females, however, bigger is better, since the larger she is, the more eggs she can produce. So, the organ removal by the males seems to be a compromise solution. The alternative of evolving a single pedipalp is probably too difficult, because biology prefers symmetry. And ripping one off is a quick, easy operation, and it gets the job done.

But it does make you wonder: what possessed the first male spider to try tearing off a part of himself?

Bedbug Penis Tasting

Bedbugs are not a particularly romantic lot. For the males, sex is wham, bam, thank you ma’am. The females, on the other hand, are a deceptive bunch, each trying to appear chaste, even virginal, in their attempt to attract the male with the most sperm. But male bedbugs have their own means of testing a lady’s virtue. They’ve developed a phallus that can detect whether a female they’ve mated with has been faithful. Dr. Michael Siva-Jothy, an evolutionary physiologist at the University of Sheffield in England, thinks that this is an adaptation that prevents the males from wasting sperm.

Before we get to the perceptive penis, here are some other interesting facts about bedbug sex that are worth knowing. First, even though the females have a fully developed reproductive tract, the males don’t use it. It’s strictly for laying eggs. Dr. Siva-Jothy explains this oddity: “The male’s penis is like a hypodermic needle. He stabs it into the body wall of the female, and he inseminates directly into her body cavity. Now, that’s pretty strange.” Pretty strange, indee...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMcClelland & Stewart

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0771079680

- ISBN 13 9780771079689

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages296

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 42.51

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Nasty, Brutish, and Short: The Quirks and Quarks Guide to Animal Sex and Other Weird Behaviour

Published by

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771079680

ISBN 13: 9780771079689

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0771079680-2-1

Buy New

US$ 42.51

Convert currency

Nasty, Brutish, and Short: The Quirks and Quarks Guide to Animal Sex and Other Weird Behaviour

Published by

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771079680

ISBN 13: 9780771079689

New

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0771079680-new

Buy New

US$ 42.52

Convert currency

Nasty, Brutish, and Short: The Quirks and Quarks Guide to Animal Sex and Other Weird Behaviour

Published by

McClelland & Stewart Ltd

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771079680

ISBN 13: 9780771079689

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 224 pages. 8.50x5.50x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0771079680

Buy New

US$ 30.10

Convert currency