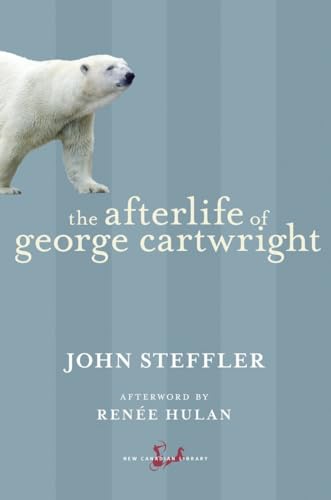

Items related to The Afterlife of George Cartwright

In this stunning and original novel, John Steffler has recreated a lost time and place, and has given life to an enigmatic figure from Canada’s 18th-century past. Described quietly by historians as “soldier, diarist, entrepreneur,” George Cartwright emerges in Steffler’s tale as a character of overwhelming appetite and ambition. Until this time Cartwright’s greatest legacy has been the place in Labrador named after him and the journal he wrote during his years there, when he lived amongst Native people and ran a successful trading post. Now his legacy becomes our own: a telling portrait of our past; a warning.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

John Steffler was born in Toronto and currently lives in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, where he teaches at Memorial University’s Sir Wilfred Grenfell College.

An acclaimed poet, his most recent books of poetry are The Grey Islands and The Wreckage of Play. The Afterlife of George Cartwright, published in Canada and the U.S., won the 1992 Smithbooks/Books in Canada First Novel Award, the 1993 Thomas Raddall Award, and was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for Fiction and for the 1993 Best First Book Commonwealth Prize.

John Steffler is currently at work on his next novel.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

An acclaimed poet, his most recent books of poetry are The Grey Islands and The Wreckage of Play. The Afterlife of George Cartwright, published in Canada and the U.S., won the 1992 Smithbooks/Books in Canada First Novel Award, the 1993 Thomas Raddall Award, and was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for Fiction and for the 1993 Best First Book Commonwealth Prize.

John Steffler is currently at work on his next novel.

One

Nottinghamshire shimmers. Fragrant, dizzy with bees at the peak of May. Turning around in the saddle, George Cartwright squints at the scattered fields – no birds within range, no sign of another person. Never a sign of another person. He lets his horse carry him on at its own easy pace, following the Nottingham road out from Mansfield, the same route he’s taken every day since his death in 1819. His hawk, Kaumalak, is perched on his left fist. Sunlight pricks blue fire from the feathers of her wings, and

Cartwright smoothes her iridescence: this dainty mortar shell. Songs from invisible birds beckon him forward, stirring his appetite for the hunt. For the moment, his loneliness is nearly without pain. Sparrows splash in the puddled wagon tracks ahead, but he keeps his hawk hooded, scanning the pastures and groves, waiting for larks. Cartwright knows he’s dead, but death isn’t the way he expected – although after 170 years it isn’t something that troubles him very much anymore. In the last weeks of his life, riding this same well- known road, feeling his hawk unusually heavy on his glove, he had sensed the end coming and wondered what lay beyond. Not harps and angels, he suspected, but at least a brief audience with his Maker. Probably a reunion with family and old acquaintances who had already died – some he wasn’t so sure he wanted to face again, but even that he was curious about. Forgiveness and understanding would likely prevail. Maybe a new incarnation in a new world awaited him, something as unimaginable as Labrador. Certainly explanations and marvels, and a few rewards. He didn’t anticipate many punishments. God, he assumed, under his aura or robes or whatever, would be a manly gentleman who favoured a bit of push and gusto in his chaps on earth. But instead of any of that, he died in his room at The Turk’s Head in Mansfield and woke up there, and nothing had changed. Except time had stopped, at least in his immediate vicinity, and everyone was away somewhere. All he could think to do was go hawking.

This morning, for example, like every morning, he had sat on the edge of his bed in The Turk’s Head Inn – after a night of unspeakable dreams – and had thought about his unfinished affairs in Labrador, about Caubvick, the Inuit woman, and Mrs. Selby, his mistress, wondering how he might have kept them with him during his days alive. And as he sat picturing their beautiful, troubled faces, speaking to them in his mind, making them smile, and as he proved to himself once again that his bankrupt business might have been saved, his ruminations were mixed with a constant awareness of the smell of damp soot in the fireplace and of the soundlessness of the building around him, the deserted taproom downstairs, Mansfield’s deserted houses, deserted streets. And then, sitting hopelessly, he noticed Kaumalak on her perch. Her keen eyes and beak. Her economical movements. Her stern looks. And in his heart Cartwright felt, with a surge of gladness, the old desire to hunt, to feel the kick of his Hanoverian rifle or the push of his peregrine’s talons as she launched herself in a burst at the sight of doves. He looked out his window then at his horse, Thoroton, stabled across the courtyard, and began hurrying, whistling, getting into his boots.

Although time has stopped for Cartwright, he knows that just beneath the surface of what surrounds him it has been racing along at an insane speed. He’s discovered that time is like sound – that the past doesn’t vanish, but encircles us in layers like a continuous series of voices, with the closest, most recent voice drowning out those that have gone before. And just as it’s possible to sit on a bench in a city reading a book, oblivious to the complex racket all around, then to withdraw from the page and pick out from the cascade of noises the voice of one street vendor two blocks away, so for Cartwright it’s possible at times to tune in a detail from either the past or the ongoing course of time and, by concentrating on it, become witness to some event in the affairs of the dead or the living.

For the living, the past is always overlaid, made inaccessible by the present, but for Cartwright, both the past and the present are elusive background phenomena, subject to occasional capture. His experience as a hunter and his 170 years of practice have made him adept at nabbing rare moments by their whiskers or tails. He even stumbles into pockets of time unintentionally, the way he’s often stumbled into a rabbit hole during his rambles in search of game.

Right now while Thoroton plods and the saddle creaks, Cartwright’s eye is caught by a red glimmer ahead in the roadside grass. A ring dropped by some lady or gentleman? A berry? A beetle? The ruby gleam rapidly grows in size and hurtles toward him, pulling in its wake a black river of pavement and two wide wings of images: sharp- cornered brick buildings in rows on either side, poles and wires, smoke. The scarlet double- decker Trent Lines bus bearing down on him is a familiar sight. It rushes under or through him, at which point Cartwright sees it, feels its rush, but can’t see his horse or himself. Groups of cars plunge through him from both directions. He seems to whirl upward, enlarged on an eddy of turbulence, feeling a mixture of horror and admiration. To ride in one of those things! The inventor and sportsman in him are aroused. And yet he’s annoyed. He has spied enough on the present to know how small, how mechanical people there have become. Children of Edmund, he thinks, remembering his brother Edmund’s power- loom and gunpowder engine. This is where all that led. And then remembering his own attempted inventions, he admits to himself some blame for this state of affairs.

At certain periods Cartwright has been a fan of the present, though usually a rather grudging, critical fan, following it more out of idle curiosity than love. For a while the smell of the lichen on an oak tree in Averham Park was a reliable way of getting into the Robin Hood Tavern in Nottingham, and although the effort required to trace the smell into the tavern and keep himself there was extremely draining, Cartwright had spent many hours standing by The Robin Hood’s coat- rack watching television and reading the paper over the shoulder of a retired dry- cleaner who always sat nearby and whom Cartwright regarded as more dead than himself. He was actually quite interested in Nottingham Forest, the local football team, for a time – knew all the players and their statistics, laughed at the barbaric remarks of their manager, Brian Clough. But then the effort became too much, and he felt foolish, and went back to his hawk and the Nottingham road. It was lonely and predictable there on the whole, but at least it was his death, and there must be some purpose in it, he thought.

The red gleam, the Trent bus, had taken Cartwright by surprise. After a moment he recomposes himself and looks around from his elevated position over the countryside. He is out of the present again. The landscape he sees now is the familiar one, exactly as it was on the 19th of May in 1819, the day he died. To the east he sees the old family estate at Marnham and to the south, near Newark, his father’s famous bridge, far from any water, like a length of Roman aqueduct, the folly that had swallowed what little was left of the family fortune and had sent Cartwright into the army and to Labrador. Buttercups and grasses festoon its parapets. A small herd of cows enjoys the shade under one of its spans.

Perhaps he’s borrowing Kaumalak’s eyes. This ability of his to stretch up and scan the surface of the earth is getting stronger, he’s noticed. It works best, for some reason, on horseback from the top of a hill. He has seen as far east as Saxony, where he was injured by a boar for the sake of the ungrateful Marquis of Granby, and even to Minorca where he nearly died of fever. To the west he has seen Lizard Head and the Scilly Isles where more than once he came close to being shipwrecked returning from Labrador. He has seen as far as the mid- Atlantic, the same mountainous grey and yellow waves that had rolled clean over his leaking ships. But not yet as far as Newfoundland and the Labrador coast.

Cartwright rises slightly in his saddle and farts and searches the sky over the meadows for larks. No, the present causes him little envy. The past is what he can’t let alone.

He turns Thoroton to the left through an open gate onto a cattle track and immediately flushes a pair of pheasants from beyond a hedge. He deftly releases his hawk’s jesses and takes off her hood. She swivels her head once, unfolds her wings, and kicks back hard as he braces himself in the stirrups and throws up his arm, pushing with all his might against the amazing force.

Nottinghamshire slips from Cartwright’s lap like a quilt. He watches his hands shoot out far, fingers hooked for the pleasure of catching. For feeling the quick pulse burst into bloom, red petals scattering.

His centre melts, a current of hunger surging out of his throat and eyes in his hawk’s wake. His body forgotten on Thoroton’s back.

Diving into a pocket of blood in the sky. Pure fugitive treasure. The motherhood under everything, even rocks and ice.

Kaumalak has disappeared in the sun. Cartwright hangs suspended, waiting, hearing a pasture gate lazily striking its post in the light breeze, pausing, striking.

Like that knocking on board the Mary during his first voyage home from Labrador. The sound belonged to the part of his cargo he couldn’t understand; the most precious part, he now thinks, the most curious of all he carried from Labrador. The sound of beliefs fathered in people by icebergs and rocks.

Having lost sight of land east of Belle Isle, the Mary broke into her full ocean roll, creaking without restraint. Mrs. Selby had made a nest for herself on some bales of marten pelts by the window at the stern and was reading a book. Beside her a set of caribou antlers was lashed to the cabin wall. A tall willow cage containing an eagle swung from an antler point. Cartwright sat at a table making entries in his journal, pleased to be bound for home. Every inch of the ship was snug with cargo, the fruit of a two- year stay in Labrador.

“1772. November. Sunday 8,” he had written, “Wind N.N.E. fresh. At day- break we put to sea from Chateau, and set sail for Ireland. We found a great sea in the straits, and by mid- afternoon are two leagues to the eastward of the island of Belle Isle.” Pausing to match his hand to the ship’s movement, he became aware of repeated knocking in the next cabin, not in time with the pitch and roll. He rose, exchanged a questioning look with Mrs. Selby, then stepped out to investigate, opened the nearest door.

The smell of the Inuit: woodsmoke and old fat. Only slightly different from his own smell after being surrounded for so long by dried fish, furs, barrels of oil from the cooked blubber of seals. Ickcongoque was lying on her back on the small cabin floor. Her husband, Attuiock, knelt a few feet from her head, chanting slowly and mournfully. Using a musket’s ramrod as a lever balanced over a pewter jug, he was raising Ickcongoque’s head by means of a leather thong which hung from the ramrod’s end and passed under the back of her neck. Their four- year- old daughter, Ickeuna, was snuggled in Caubvick’s lap, both of them fixedly watching the rite. Caubvick’s husband, Tooklavinia, was asleep in one of the bunks. Caubvick turned her beautiful face to Cartwright and smiled when she heard him come in.

Attuiock chanted monotonously, his eyes shut, then opened them wide, hissed a couple of words with great intensity, and let Ickcongoque’s head drop to the cabin floor. Then he began his chanting again, raising Ickcongoque’s head.

Cartwright waited, watching intently, as he had done so often with these people, glad of their incomprehensible displays. Attuiock paused, looking proud and wise. “It is very good, very good,” he said, pointing to Ickcongoque and his device.

“That may be,” Cartwright nodded, “but pray, what is it good for?”

“My wife has got the headache.”

“Ah!” Cartwright raised his eyebrows and quickly withdrew.

Three strides up the companionway, hit by the tilting bite of the air, he gripped the rail and let his laughter explode. He was rich, he knew it. The old chief ’s solemn face! How he loved him, his childishness and wisdom – always what Cartwright loved: dignity and fantasy combined.

Cartwright could see his success. His cargoes wouldn’t completely repay his debts, but they would impress his creditors, bringing investment for his next trip out, for expanding his operations on the Labrador coast. He would speak about that with the Board of Trade. And the Inuit would bring him renown, audiences with curious grandees, people of influence – perhaps with the King himself. Some gifts of furs and curios for the men on the Board of Trade, and for Cartwright sole right to fish and hunt in the watersheds of the St. Lewis River and the Alexis River, and eventually Sandwich Bay. And Noble and Pinson’s territory as well – he would have to devour those rivals who were trying to squeeze him out. And better naval support – British law to hold it all in place. Tall doors opening everywhere to admit the adventurer- gentleman back from the Empire’s outposts with proofs of supremacy. He wanted that. Thick- headed George Cartwright, the sporting dolt. He knew what his brothers thought of him. A failed soldier, forever in debt, retired young on half- pay with nothing to do and not enough money with which to do it.

He felt himself grin at the prospect of showing off England to the Inuit, watching their faces as they rode in a coach through London’s streets. As they entered St. Paul’s. He liked their capacity for awe, and the thought of the tales they’d take back to their people in Labrador. They looked on the English as a small tribe of landless wanderers. He wanted to show them the true proportion of things, amaze them, make them willing subjects of his rule, to both their advantages. He needed to keep them working for him, bringing him whalebone and furs; he wanted them to see that they needed his knowledge and goods in exchange.

He imagined their comic conjectures and his explanations, their blunders in high society. He was eager for this, the disruption they’d cause. He felt they embodied a part of him self returning home. He had never fitted into London society. He was happier gutting a deer. He pictured himself in London walking his wolf cub on a leash, carrying his eagle, escorted by Inuit, and felt the power they gave him – not merely because of the spectacle, but because they were his natural company. They proclaimed what he’d always harboured inside himself.

His youngest sister, Dorothy, would be frightened, filled with wonder. His brothers would be speechless for a change. In their chairs in the parlour at Marnham. Political pamphlets, inventions, and sonnets would be swept from their minds as they watched him stride ab...

Nottinghamshire shimmers. Fragrant, dizzy with bees at the peak of May. Turning around in the saddle, George Cartwright squints at the scattered fields – no birds within range, no sign of another person. Never a sign of another person. He lets his horse carry him on at its own easy pace, following the Nottingham road out from Mansfield, the same route he’s taken every day since his death in 1819. His hawk, Kaumalak, is perched on his left fist. Sunlight pricks blue fire from the feathers of her wings, and

Cartwright smoothes her iridescence: this dainty mortar shell. Songs from invisible birds beckon him forward, stirring his appetite for the hunt. For the moment, his loneliness is nearly without pain. Sparrows splash in the puddled wagon tracks ahead, but he keeps his hawk hooded, scanning the pastures and groves, waiting for larks. Cartwright knows he’s dead, but death isn’t the way he expected – although after 170 years it isn’t something that troubles him very much anymore. In the last weeks of his life, riding this same well- known road, feeling his hawk unusually heavy on his glove, he had sensed the end coming and wondered what lay beyond. Not harps and angels, he suspected, but at least a brief audience with his Maker. Probably a reunion with family and old acquaintances who had already died – some he wasn’t so sure he wanted to face again, but even that he was curious about. Forgiveness and understanding would likely prevail. Maybe a new incarnation in a new world awaited him, something as unimaginable as Labrador. Certainly explanations and marvels, and a few rewards. He didn’t anticipate many punishments. God, he assumed, under his aura or robes or whatever, would be a manly gentleman who favoured a bit of push and gusto in his chaps on earth. But instead of any of that, he died in his room at The Turk’s Head in Mansfield and woke up there, and nothing had changed. Except time had stopped, at least in his immediate vicinity, and everyone was away somewhere. All he could think to do was go hawking.

This morning, for example, like every morning, he had sat on the edge of his bed in The Turk’s Head Inn – after a night of unspeakable dreams – and had thought about his unfinished affairs in Labrador, about Caubvick, the Inuit woman, and Mrs. Selby, his mistress, wondering how he might have kept them with him during his days alive. And as he sat picturing their beautiful, troubled faces, speaking to them in his mind, making them smile, and as he proved to himself once again that his bankrupt business might have been saved, his ruminations were mixed with a constant awareness of the smell of damp soot in the fireplace and of the soundlessness of the building around him, the deserted taproom downstairs, Mansfield’s deserted houses, deserted streets. And then, sitting hopelessly, he noticed Kaumalak on her perch. Her keen eyes and beak. Her economical movements. Her stern looks. And in his heart Cartwright felt, with a surge of gladness, the old desire to hunt, to feel the kick of his Hanoverian rifle or the push of his peregrine’s talons as she launched herself in a burst at the sight of doves. He looked out his window then at his horse, Thoroton, stabled across the courtyard, and began hurrying, whistling, getting into his boots.

Although time has stopped for Cartwright, he knows that just beneath the surface of what surrounds him it has been racing along at an insane speed. He’s discovered that time is like sound – that the past doesn’t vanish, but encircles us in layers like a continuous series of voices, with the closest, most recent voice drowning out those that have gone before. And just as it’s possible to sit on a bench in a city reading a book, oblivious to the complex racket all around, then to withdraw from the page and pick out from the cascade of noises the voice of one street vendor two blocks away, so for Cartwright it’s possible at times to tune in a detail from either the past or the ongoing course of time and, by concentrating on it, become witness to some event in the affairs of the dead or the living.

For the living, the past is always overlaid, made inaccessible by the present, but for Cartwright, both the past and the present are elusive background phenomena, subject to occasional capture. His experience as a hunter and his 170 years of practice have made him adept at nabbing rare moments by their whiskers or tails. He even stumbles into pockets of time unintentionally, the way he’s often stumbled into a rabbit hole during his rambles in search of game.

Right now while Thoroton plods and the saddle creaks, Cartwright’s eye is caught by a red glimmer ahead in the roadside grass. A ring dropped by some lady or gentleman? A berry? A beetle? The ruby gleam rapidly grows in size and hurtles toward him, pulling in its wake a black river of pavement and two wide wings of images: sharp- cornered brick buildings in rows on either side, poles and wires, smoke. The scarlet double- decker Trent Lines bus bearing down on him is a familiar sight. It rushes under or through him, at which point Cartwright sees it, feels its rush, but can’t see his horse or himself. Groups of cars plunge through him from both directions. He seems to whirl upward, enlarged on an eddy of turbulence, feeling a mixture of horror and admiration. To ride in one of those things! The inventor and sportsman in him are aroused. And yet he’s annoyed. He has spied enough on the present to know how small, how mechanical people there have become. Children of Edmund, he thinks, remembering his brother Edmund’s power- loom and gunpowder engine. This is where all that led. And then remembering his own attempted inventions, he admits to himself some blame for this state of affairs.

At certain periods Cartwright has been a fan of the present, though usually a rather grudging, critical fan, following it more out of idle curiosity than love. For a while the smell of the lichen on an oak tree in Averham Park was a reliable way of getting into the Robin Hood Tavern in Nottingham, and although the effort required to trace the smell into the tavern and keep himself there was extremely draining, Cartwright had spent many hours standing by The Robin Hood’s coat- rack watching television and reading the paper over the shoulder of a retired dry- cleaner who always sat nearby and whom Cartwright regarded as more dead than himself. He was actually quite interested in Nottingham Forest, the local football team, for a time – knew all the players and their statistics, laughed at the barbaric remarks of their manager, Brian Clough. But then the effort became too much, and he felt foolish, and went back to his hawk and the Nottingham road. It was lonely and predictable there on the whole, but at least it was his death, and there must be some purpose in it, he thought.

The red gleam, the Trent bus, had taken Cartwright by surprise. After a moment he recomposes himself and looks around from his elevated position over the countryside. He is out of the present again. The landscape he sees now is the familiar one, exactly as it was on the 19th of May in 1819, the day he died. To the east he sees the old family estate at Marnham and to the south, near Newark, his father’s famous bridge, far from any water, like a length of Roman aqueduct, the folly that had swallowed what little was left of the family fortune and had sent Cartwright into the army and to Labrador. Buttercups and grasses festoon its parapets. A small herd of cows enjoys the shade under one of its spans.

Perhaps he’s borrowing Kaumalak’s eyes. This ability of his to stretch up and scan the surface of the earth is getting stronger, he’s noticed. It works best, for some reason, on horseback from the top of a hill. He has seen as far east as Saxony, where he was injured by a boar for the sake of the ungrateful Marquis of Granby, and even to Minorca where he nearly died of fever. To the west he has seen Lizard Head and the Scilly Isles where more than once he came close to being shipwrecked returning from Labrador. He has seen as far as the mid- Atlantic, the same mountainous grey and yellow waves that had rolled clean over his leaking ships. But not yet as far as Newfoundland and the Labrador coast.

Cartwright rises slightly in his saddle and farts and searches the sky over the meadows for larks. No, the present causes him little envy. The past is what he can’t let alone.

He turns Thoroton to the left through an open gate onto a cattle track and immediately flushes a pair of pheasants from beyond a hedge. He deftly releases his hawk’s jesses and takes off her hood. She swivels her head once, unfolds her wings, and kicks back hard as he braces himself in the stirrups and throws up his arm, pushing with all his might against the amazing force.

Nottinghamshire slips from Cartwright’s lap like a quilt. He watches his hands shoot out far, fingers hooked for the pleasure of catching. For feeling the quick pulse burst into bloom, red petals scattering.

His centre melts, a current of hunger surging out of his throat and eyes in his hawk’s wake. His body forgotten on Thoroton’s back.

Diving into a pocket of blood in the sky. Pure fugitive treasure. The motherhood under everything, even rocks and ice.

Kaumalak has disappeared in the sun. Cartwright hangs suspended, waiting, hearing a pasture gate lazily striking its post in the light breeze, pausing, striking.

Like that knocking on board the Mary during his first voyage home from Labrador. The sound belonged to the part of his cargo he couldn’t understand; the most precious part, he now thinks, the most curious of all he carried from Labrador. The sound of beliefs fathered in people by icebergs and rocks.

Having lost sight of land east of Belle Isle, the Mary broke into her full ocean roll, creaking without restraint. Mrs. Selby had made a nest for herself on some bales of marten pelts by the window at the stern and was reading a book. Beside her a set of caribou antlers was lashed to the cabin wall. A tall willow cage containing an eagle swung from an antler point. Cartwright sat at a table making entries in his journal, pleased to be bound for home. Every inch of the ship was snug with cargo, the fruit of a two- year stay in Labrador.

“1772. November. Sunday 8,” he had written, “Wind N.N.E. fresh. At day- break we put to sea from Chateau, and set sail for Ireland. We found a great sea in the straits, and by mid- afternoon are two leagues to the eastward of the island of Belle Isle.” Pausing to match his hand to the ship’s movement, he became aware of repeated knocking in the next cabin, not in time with the pitch and roll. He rose, exchanged a questioning look with Mrs. Selby, then stepped out to investigate, opened the nearest door.

The smell of the Inuit: woodsmoke and old fat. Only slightly different from his own smell after being surrounded for so long by dried fish, furs, barrels of oil from the cooked blubber of seals. Ickcongoque was lying on her back on the small cabin floor. Her husband, Attuiock, knelt a few feet from her head, chanting slowly and mournfully. Using a musket’s ramrod as a lever balanced over a pewter jug, he was raising Ickcongoque’s head by means of a leather thong which hung from the ramrod’s end and passed under the back of her neck. Their four- year- old daughter, Ickeuna, was snuggled in Caubvick’s lap, both of them fixedly watching the rite. Caubvick’s husband, Tooklavinia, was asleep in one of the bunks. Caubvick turned her beautiful face to Cartwright and smiled when she heard him come in.

Attuiock chanted monotonously, his eyes shut, then opened them wide, hissed a couple of words with great intensity, and let Ickcongoque’s head drop to the cabin floor. Then he began his chanting again, raising Ickcongoque’s head.

Cartwright waited, watching intently, as he had done so often with these people, glad of their incomprehensible displays. Attuiock paused, looking proud and wise. “It is very good, very good,” he said, pointing to Ickcongoque and his device.

“That may be,” Cartwright nodded, “but pray, what is it good for?”

“My wife has got the headache.”

“Ah!” Cartwright raised his eyebrows and quickly withdrew.

Three strides up the companionway, hit by the tilting bite of the air, he gripped the rail and let his laughter explode. He was rich, he knew it. The old chief ’s solemn face! How he loved him, his childishness and wisdom – always what Cartwright loved: dignity and fantasy combined.

Cartwright could see his success. His cargoes wouldn’t completely repay his debts, but they would impress his creditors, bringing investment for his next trip out, for expanding his operations on the Labrador coast. He would speak about that with the Board of Trade. And the Inuit would bring him renown, audiences with curious grandees, people of influence – perhaps with the King himself. Some gifts of furs and curios for the men on the Board of Trade, and for Cartwright sole right to fish and hunt in the watersheds of the St. Lewis River and the Alexis River, and eventually Sandwich Bay. And Noble and Pinson’s territory as well – he would have to devour those rivals who were trying to squeeze him out. And better naval support – British law to hold it all in place. Tall doors opening everywhere to admit the adventurer- gentleman back from the Empire’s outposts with proofs of supremacy. He wanted that. Thick- headed George Cartwright, the sporting dolt. He knew what his brothers thought of him. A failed soldier, forever in debt, retired young on half- pay with nothing to do and not enough money with which to do it.

He felt himself grin at the prospect of showing off England to the Inuit, watching their faces as they rode in a coach through London’s streets. As they entered St. Paul’s. He liked their capacity for awe, and the thought of the tales they’d take back to their people in Labrador. They looked on the English as a small tribe of landless wanderers. He wanted to show them the true proportion of things, amaze them, make them willing subjects of his rule, to both their advantages. He needed to keep them working for him, bringing him whalebone and furs; he wanted them to see that they needed his knowledge and goods in exchange.

He imagined their comic conjectures and his explanations, their blunders in high society. He was eager for this, the disruption they’d cause. He felt they embodied a part of him self returning home. He had never fitted into London society. He was happier gutting a deer. He pictured himself in London walking his wolf cub on a leash, carrying his eagle, escorted by Inuit, and felt the power they gave him – not merely because of the spectacle, but because they were his natural company. They proclaimed what he’d always harboured inside himself.

His youngest sister, Dorothy, would be frightened, filled with wonder. His brothers would be speechless for a change. In their chairs in the parlour at Marnham. Political pamphlets, inventions, and sonnets would be swept from their minds as they watched him stride ab...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherNew Canadian Library

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0771093985

- ISBN 13 9780771093982

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages304

- Rating

US$ 16.08

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Afterlife of George Cartwright

Published by

New Canadian Library

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771093985

ISBN 13: 9780771093982

Used

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.6. Seller Inventory # G0771093985I4N00

Buy Used

US$ 16.08

Convert currency

The Afterlife of George Cartwright

Published by

New Canadian Library

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771093985

ISBN 13: 9780771093982

Used

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.6. Seller Inventory # G0771093985I3N00

Buy Used

US$ 16.08

Convert currency