Items related to Fannie's Last Supper: Two Years, Twelve Courses,...

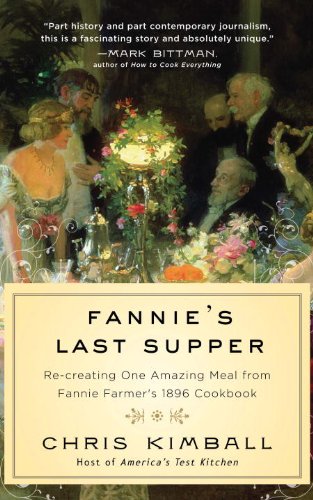

Fannie's Last Supper: Two Years, Twelve Courses, and One Amazing Meal from Fannie Farmer's 1896 Cookbook - Hardcover

Before The Joy of Cooking, there was The Boston Cooking School Cookbook. Written by Fannie Farmer, principal of the school, and published in 1896, it was the bestselling cookbook of its age. 400,000 copies were sold by Farmer's death in 1915 — and more than 4 million were sold by the 1960s. It perfectly encapsulates the late Victorian era, but it's also surprisingly modern; in short, it's ripe for reevaluation. And who better to conduct such an experiment than Chris Kimball, founder of Cook's Illustrated and host of PBS's America's Test Kitchen? Fannie's Last Supper is the result. In it, Kimball assembles an extravagant 12-course Christmas dinner from Farmer's cookbook and serves it in an 1859 Boston townhouse, complete with an authentic Victorian home kitchen, uniformed maids, and a distinguished guest list. The menu includes Roast Goose with Potato Stuffing, Canton Punch, Three Moulded Victorian Jellies, and Mandarin Cake. But Kimball includes more than just the dinner party's dishes — Fannie's Last Supper is a working cookbook with tested, rewritten, updated recipes drawn from Farmer's opus. It's a culinary thriller of sorts, travelling back in time to reexamine something most of us take for granted: the North American table.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

CHRIS KIMBALL founded Cook's Magazine in 1980. Now known as Cook's Illustrated, it has a paid circulation of 1,000,000. He also hosts America's Test Kitchen and Cook's Country, the top-rated cooking shows on public television.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

A Culinary Time Machine

A Seat at the Victorian Table

A high Victorian dinner party was a modern re-creation of the ancient ritual of class and culinary artistry, displaying the plumage of high society while underlining the rigid rules of proper social intercourse. It was tails for the gentlemen and full dress costume for the ladies. One was expected to arrive neither early nor more than fifteen minutes late. When dinner was announced, the guests were led in pro cession from parlor to dining room, the host escorting the honored lady of the evening. The standard twelve courses were to be served briskly, in no more than two hours, yet there were few restraints on the amount of silverware used, with up to 131 separate pieces per setting in myriad styles from neoclassical, Persian, and Elizabethan to Jacobean, Japa nese, Etruscan, and even Moorish. The rules of behavior were well known to all diners: one was never to appear greedy, draining the last drop from a wineglass or scraping the final morsel from the plate; one never ate hurriedly, which implied uncontrolled hunger; and since meal preparation was not something to be shown in public, plates were prepared out of view.

Within this rigid construct, food was the creative spark, the manna for imagination, and the kitchen a place where one was at last allowed to express one’s wildest desires. Victorian jellies with ribbons of colors and flavors, Bavarian cream fillings, and hundreds of custom molds were a culinary free-for-all, as was the sheer variety of a twelve-course menu, from oysters and champagne to fish, turtle, goose, venison, duck, chicken, beef, vegetables, salads, cakes, bonbons, coffee, and liqueurs, all carefully orchestrated from soup to crackers to provide an eclectic, wide-ranging array of tastes and textures. Among the very wealthy, these dinners occasionally crossed the line from artistic perfection to excess, with menus that included roasted lion, naked cherubs leaping out from live-nightingale pies, chimps in tuxedos feted as guests of honor, and gentlemen in black tie dining on horse back. The Victorian dinner table was a moment in time that encapsulated the dreams of a young country—the radical pace of change from farm to city, from water to steam power, from local to international, from poor to rich—that defined our nineteenth century, and this food, these menus, this dining experience have today remained dormant for over a century, just waiting to be rediscovered: the old cast-iron stove lit once again, the venison roasted, the geese plucked, and the dining table decorated using the furthest reaches of culinary imagination.

And so, in 2007, with Fannie Farmer’s original 1896 Boston Cooking School cookbook in hand, using a twelve-course menu printed in the back of the book and an authentic Victorian coal cookstove installed in our 1859 Boston town house, I set out on a two-year journey: to test, update, and master the cooking of Fannie Farmer’s America, re-creating a high Victorian feast that I hoped to serve in perfect succession to a dozen celebrity guests for a televised public tele vi sion special.

The project had begun with a book. It was horse chestnut brown, the color of a dark penny roux, mottled through a century of use, and measuring just 5 by 73⁄4 inches. The cover had separated from the binding, and there was no printing on the front or back—just a simple mustard yellow title on the upper spine: Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book. It was subtitled, on the inside, What to Do and What Not to Do in Cooking. The book was published in Boston by Roberts Brothers in 1890, seven years after the first edition; it was 536 pages. In 1896, Fannie Farmer, the new head of the Boston Cooking School, revised, updated, and expanded Mrs. Lincoln’s work.

I had found it in 1983 through an act of pure serendipity, in the library of a house I was thinking of purchasing at the top of Mine Hill Road in Fairfield, Connecticut. It was a two-story white clapboard number, more a square than a colonial rectangle, well proportioned and big enough for a small family, but no trophy house by any stretch. The former occupant, well in her eighties, had just died; she had been the German mistress of a long-departed lawyer in town who had willed her the use of the house during her lifetime. Coming up the back steps into the kitchen for our first inspection, my wife-to-be, Adrienne, and I noticed the antique gas stove, the even older four-door General Motors refrigerator, and a screen door between the kitchen and the dining room, as if the occupant had kept live chickens or goats secluded from the rest of the living quarters.

As the Realtor took Adrienne on a tour of the upstairs, I sat on a window seat and read the preface of the small cookbook I’d found abandoned on a shelf. In it, Mrs. Lincoln put forth her premise: to compile a book “which shall also embody enough of physiology, and of the chemistry and philosophy of food.” Hmm, that sounded quite modern to me, hardly what I might have expected from a book published in 1890. She went on to define cooking as “the art of preparing food for the nourishment of the human body. [Cooking] must be based upon scientific principles of hygiene and what the French call the minor moralities of the house hold. The degree of civilization is often mea sured by its cuisine.” Clearly, she was a heck of a lot more enlightened regarding cooking and diet than 99 percent of all cookbook authors today, most of whom were promising meals in minutes.

Who were these Victorian cooks? Years later, while researching this book, I came across an awe-inspiring account of the Boston Food Fair of 1896. This made the contemporary Fancy Food Show look like amateur hour. A series of over-the-top meals was served, including a “Mermaid’s Dinner.” There was an electric dairy in the convention hall that churned out three thousand pounds of butter each day, a towering replica of a castle to promote flour, and a giant barn with grass, trees, and a Paul Bunyan– sized cow whose only purpose was to promote canned evaporated cream. Women queued up for free samples from two hundred different vendors: shredded wheat, cereals, gelatins, extracts, ice cream, candy, and custards. Other booths promoted shredded fish, preserved fruits, olives, baking powders, and dried meats. And then, just to remind us that we were still in the Victorian age, tucked darkly under the stairs, was the perfect dour touch: a melancholy exhibit of gravestones to remind passers by of their inevitable end. Just as today, food and cooking were at the convergence of popular entertainment and capitalism.

In fact, in the late 1800s, the culinary world was on fire, as technology came to the rescue of the exhausted home cook with modern versions of classic ingredients. Powdered gelatin had recently replaced ungainly thickeners such as isinglass, made from the swim bladders of sturgeon, or Irish moss, made from seaweed, or, God forbid, calf’s-foot jelly, a smelly proposition indeed. Jell-O was even marketing an ice-cream powder in vanilla, strawberry, chocolate, and lemon as an alternative to making the real thing. Gas stoves were coming into use, replacing dirty, high-maintenance coal cookstoves. Fruits were being shipped in from California and the Northwest, mushrooms from France, extra-virgin olive oil from Italy, and cheese from all over Eu rope, including real Parmesan and Emmanthaler. Sugar was now modern and highly refined, no longer consumed in yellow loaves, but pure white and granulated. Contemporary cookbooks, especially The Epicurean by Charles Ranhofer, exhibited an advanced knowledge of cooking and the assumption that home cooks were up to the task of creating elaborate masterpieces.

Then a strange and self-indulgent notion struck me. Trying to understand the culinary past through old cookbooks and newspapers is a dodgy enterprise at best. A century or two from now, would historians be able to paint an accurate picture of home cooking in the early twenty-first century by reading the New York Times food pages or looking at Amazon best-sellers in the Cooking, Food, and Wine category? Instead, why not just cook my way back through history—investigate the ingredients and the techniques; make the puddings, the soups, the roasts, the jellies, and the cakes; and then give myself a final exam, a twelve-course Victorian blowout dinner party that I would serve to the most interesting group of guests I could cobble together? Oh, and I should do all of this on an authentic coal cookstove from the period and make everything from scratch, including the stocks, the puff pastry, the gelatin, and the food colorings. It would be like building a culinary time machine: I could travel back through history and stand next to Fannie as she cooked, feeling the intense heat of the cast-iron stove and the chill of the thin strips of salt pork as I larded a saddle of venison, and then follow her instructions precisely as I handled a poached calf’s brain so gently that it did not dissolve into custard.

This idea was to remain nothing more than a daydream until 1991, when I moved to Boston and purchased an 1859 brick bowfront only a few blocks away from Fannie Farmer’s home in 1896, the year that she published The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. I still had to renovate the house and re -create an authentic Victorian kitchen—all of that would take years—but the seed had been planted. My fantasy dinner party, sleuthing the Victorian age through its recipes, was about to be born.

A Seat at the Victorian Table

A high Victorian dinner party was a modern re-creation of the ancient ritual of class and culinary artistry, displaying the plumage of high society while underlining the rigid rules of proper social intercourse. It was tails for the gentlemen and full dress costume for the ladies. One was expected to arrive neither early nor more than fifteen minutes late. When dinner was announced, the guests were led in pro cession from parlor to dining room, the host escorting the honored lady of the evening. The standard twelve courses were to be served briskly, in no more than two hours, yet there were few restraints on the amount of silverware used, with up to 131 separate pieces per setting in myriad styles from neoclassical, Persian, and Elizabethan to Jacobean, Japa nese, Etruscan, and even Moorish. The rules of behavior were well known to all diners: one was never to appear greedy, draining the last drop from a wineglass or scraping the final morsel from the plate; one never ate hurriedly, which implied uncontrolled hunger; and since meal preparation was not something to be shown in public, plates were prepared out of view.

Within this rigid construct, food was the creative spark, the manna for imagination, and the kitchen a place where one was at last allowed to express one’s wildest desires. Victorian jellies with ribbons of colors and flavors, Bavarian cream fillings, and hundreds of custom molds were a culinary free-for-all, as was the sheer variety of a twelve-course menu, from oysters and champagne to fish, turtle, goose, venison, duck, chicken, beef, vegetables, salads, cakes, bonbons, coffee, and liqueurs, all carefully orchestrated from soup to crackers to provide an eclectic, wide-ranging array of tastes and textures. Among the very wealthy, these dinners occasionally crossed the line from artistic perfection to excess, with menus that included roasted lion, naked cherubs leaping out from live-nightingale pies, chimps in tuxedos feted as guests of honor, and gentlemen in black tie dining on horse back. The Victorian dinner table was a moment in time that encapsulated the dreams of a young country—the radical pace of change from farm to city, from water to steam power, from local to international, from poor to rich—that defined our nineteenth century, and this food, these menus, this dining experience have today remained dormant for over a century, just waiting to be rediscovered: the old cast-iron stove lit once again, the venison roasted, the geese plucked, and the dining table decorated using the furthest reaches of culinary imagination.

And so, in 2007, with Fannie Farmer’s original 1896 Boston Cooking School cookbook in hand, using a twelve-course menu printed in the back of the book and an authentic Victorian coal cookstove installed in our 1859 Boston town house, I set out on a two-year journey: to test, update, and master the cooking of Fannie Farmer’s America, re-creating a high Victorian feast that I hoped to serve in perfect succession to a dozen celebrity guests for a televised public tele vi sion special.

The project had begun with a book. It was horse chestnut brown, the color of a dark penny roux, mottled through a century of use, and measuring just 5 by 73⁄4 inches. The cover had separated from the binding, and there was no printing on the front or back—just a simple mustard yellow title on the upper spine: Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book. It was subtitled, on the inside, What to Do and What Not to Do in Cooking. The book was published in Boston by Roberts Brothers in 1890, seven years after the first edition; it was 536 pages. In 1896, Fannie Farmer, the new head of the Boston Cooking School, revised, updated, and expanded Mrs. Lincoln’s work.

I had found it in 1983 through an act of pure serendipity, in the library of a house I was thinking of purchasing at the top of Mine Hill Road in Fairfield, Connecticut. It was a two-story white clapboard number, more a square than a colonial rectangle, well proportioned and big enough for a small family, but no trophy house by any stretch. The former occupant, well in her eighties, had just died; she had been the German mistress of a long-departed lawyer in town who had willed her the use of the house during her lifetime. Coming up the back steps into the kitchen for our first inspection, my wife-to-be, Adrienne, and I noticed the antique gas stove, the even older four-door General Motors refrigerator, and a screen door between the kitchen and the dining room, as if the occupant had kept live chickens or goats secluded from the rest of the living quarters.

As the Realtor took Adrienne on a tour of the upstairs, I sat on a window seat and read the preface of the small cookbook I’d found abandoned on a shelf. In it, Mrs. Lincoln put forth her premise: to compile a book “which shall also embody enough of physiology, and of the chemistry and philosophy of food.” Hmm, that sounded quite modern to me, hardly what I might have expected from a book published in 1890. She went on to define cooking as “the art of preparing food for the nourishment of the human body. [Cooking] must be based upon scientific principles of hygiene and what the French call the minor moralities of the house hold. The degree of civilization is often mea sured by its cuisine.” Clearly, she was a heck of a lot more enlightened regarding cooking and diet than 99 percent of all cookbook authors today, most of whom were promising meals in minutes.

Who were these Victorian cooks? Years later, while researching this book, I came across an awe-inspiring account of the Boston Food Fair of 1896. This made the contemporary Fancy Food Show look like amateur hour. A series of over-the-top meals was served, including a “Mermaid’s Dinner.” There was an electric dairy in the convention hall that churned out three thousand pounds of butter each day, a towering replica of a castle to promote flour, and a giant barn with grass, trees, and a Paul Bunyan– sized cow whose only purpose was to promote canned evaporated cream. Women queued up for free samples from two hundred different vendors: shredded wheat, cereals, gelatins, extracts, ice cream, candy, and custards. Other booths promoted shredded fish, preserved fruits, olives, baking powders, and dried meats. And then, just to remind us that we were still in the Victorian age, tucked darkly under the stairs, was the perfect dour touch: a melancholy exhibit of gravestones to remind passers by of their inevitable end. Just as today, food and cooking were at the convergence of popular entertainment and capitalism.

In fact, in the late 1800s, the culinary world was on fire, as technology came to the rescue of the exhausted home cook with modern versions of classic ingredients. Powdered gelatin had recently replaced ungainly thickeners such as isinglass, made from the swim bladders of sturgeon, or Irish moss, made from seaweed, or, God forbid, calf’s-foot jelly, a smelly proposition indeed. Jell-O was even marketing an ice-cream powder in vanilla, strawberry, chocolate, and lemon as an alternative to making the real thing. Gas stoves were coming into use, replacing dirty, high-maintenance coal cookstoves. Fruits were being shipped in from California and the Northwest, mushrooms from France, extra-virgin olive oil from Italy, and cheese from all over Eu rope, including real Parmesan and Emmanthaler. Sugar was now modern and highly refined, no longer consumed in yellow loaves, but pure white and granulated. Contemporary cookbooks, especially The Epicurean by Charles Ranhofer, exhibited an advanced knowledge of cooking and the assumption that home cooks were up to the task of creating elaborate masterpieces.

Then a strange and self-indulgent notion struck me. Trying to understand the culinary past through old cookbooks and newspapers is a dodgy enterprise at best. A century or two from now, would historians be able to paint an accurate picture of home cooking in the early twenty-first century by reading the New York Times food pages or looking at Amazon best-sellers in the Cooking, Food, and Wine category? Instead, why not just cook my way back through history—investigate the ingredients and the techniques; make the puddings, the soups, the roasts, the jellies, and the cakes; and then give myself a final exam, a twelve-course Victorian blowout dinner party that I would serve to the most interesting group of guests I could cobble together? Oh, and I should do all of this on an authentic coal cookstove from the period and make everything from scratch, including the stocks, the puff pastry, the gelatin, and the food colorings. It would be like building a culinary time machine: I could travel back through history and stand next to Fannie as she cooked, feeling the intense heat of the cast-iron stove and the chill of the thin strips of salt pork as I larded a saddle of venison, and then follow her instructions precisely as I handled a poached calf’s brain so gently that it did not dissolve into custard.

This idea was to remain nothing more than a daydream until 1991, when I moved to Boston and purchased an 1859 brick bowfront only a few blocks away from Fannie Farmer’s home in 1896, the year that she published The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. I still had to renovate the house and re -create an authentic Victorian kitchen—all of that would take years—but the seed had been planted. My fantasy dinner party, sleuthing the Victorian age through its recipes, was about to be born.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMcClelland & Stewart

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0771095554

- ISBN 13 9780771095559

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 77.00

Shipping:

US$ 23.00

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Fannie's Last Supper: Two Years, Twelve Courses, and One Amazing Meal from Fannie Farmer's 1896 Cookbook Kimball, Chris

Published by

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771095554

ISBN 13: 9780771095559

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # DRG1---0173

Buy New

US$ 77.00

Convert currency

Fannie*s Last Supper: Two Years, Twelve Courses, and One Amazing Meal from Fannie Farmer*s 1896 Cookbook

Published by

McClelland & Stewart

(2010)

ISBN 10: 0771095554

ISBN 13: 9780771095559

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. New. book. Seller Inventory # D7S9-1-M-0771095554-4

Buy New

US$ 212.71

Convert currency