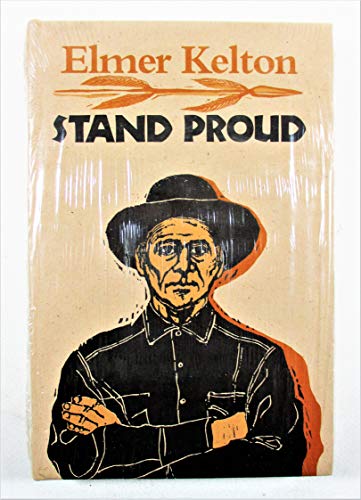

Items related to Stand Proud (Texas Tradition (Hardcover))

In Stand Proud, one of his most controversial novels, legendary Western writer Elmer Kelton takes on a character who is not as easy to like as he is to admire. Frank Claymore is cantankerous, stubborn, and intolerant--just the qualities that make him a success as an open-range cattle rancher on the West Texas frontier. Stand Proud follows Claymore form the time of the Civil War to the dawn of the twentieth century--through marriage, births, deaths, and a creeping change in the society that once hailed him as a hero, and which later has him condemned as a despoiler and tried for murder. Based in part of legendary rancher Charles Goodnight, Claymore is only one example of the many men who dreamed of cattle, and through their dedication to that dream came to change the face of Western history.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Elmer Kelton is the author of over thirty novels set in the West and the recipient of awards from the Texas Institute of Letters, the National Cowboy Hall of Fame, Western Writers of America, the Western Literature Association, and others.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

·1·

The jarring strike of the clock in the towering cupola drew Frank Claymore's unwilling eyes to the two-story courthouse. It was a Texas-plains impression of some forbidding Old World castle in which monstrous crimes had been wrought upon the innocent. Claymore had opposed the construction of this gray-stone insult, just one of many fights lost as the years stole his strength and diminished his influence. His taxes, reluctantly paid, had gone far toward building that courthouse. Now he was being tried in it, and the wolves were at his gate.

A deputy sheriff slouched at one corner of the hotel's front porch, trying to be inconspicuous as he watched Frank Claymore with nervous, weasel eyes.

There ain't no job too low for somebody who don't want to work, Claymore thought darkly.

Muttering, he moved toward a bench, attacking the floor with his cane at every step. It was hard to come to a tolerance for this kind of attention. For a time now, until just lately, it had seemed that hardly anyone except Homer Whitcomb and the hired hands paid attention to him. Older people didn't count for much anymore. He muttered a bit louder, taking crude comfort from mule-skinner language that had always been therapeutic.

Homer was at his elbow. "You say somethin', Frank?" He took Claymore's arm and tried to help him toward the bench. "You just set yourself down. Be a spell yet before court takes up again. Yonder comes the prosecutin' attorney to dinner, him and that whole pack."

Claymore jerked his arm free of Homer Whitcomb's solicitous hands. "I can set myself, thank you." Instantly he regretted his irritability, but he knew he would react no differently the next time. Long years of struggle had etched a belligerent independence into his grain, as time had conditioned the gentle Homer Whitcomb to overlook such provocations and permit them to leave no track. It had long galled Claymore that Homer showed no evidence of rheumatism, of stiffened joints that ached in protest over every quick move. Homer's hair remained indecently dark, though he was by two years the older. But, then, he had never been run over by a herd of cattle, had never carried a flint arrowhead amongst his vitals.

Homer had what Claymore regarded as a hound-dog face, loose skinned and wonderfully pliable, falling easier into smile than frown, seeming usually to harbor some private joke that he savored like old wine. To Claymore, a man who bore so little worry on his shoulders was shirking his responsibilities.

Claymore pushed aside a newspaper he found lying in the way, then settled himself upon the center of the bench so no one could share it with him. He glanced about with his eyes fierce in challenge of anyone who might have the temerity to try.

Homer asked, "Anything I can bring you, Frank?"

"I just had dinner. What the hell could I want?"

Homer seated himself in a nearby chair, showing no reaction. He was more than a working partner; he was a friend from far back down the long years. Like Frank Claymore, he had always done as he damn well pleased, and it had never pleased him to acknowledge the unpleasant.

Claymore studied the business-suited men passing through the gate of the white picket fence that surround the court-house square, picking their way among the tied horses, the wagons and buggies. His vision was still sharp when he looked into the distance. He could see the special prosecuting attorney and his own lawyer walking side by side, conversing pleasantly, apparently the best of friends.

Claymore muttered again. When a man worked for you and accepted your pay, your enemies ought to be his enemies.

He did not understand lawyers. He did not understand anybody who spent his days sheltered beneath a roof, dealing in intangibles such as law or accounts receivable rather than something solid and real like cattle and horses. It was incomprehensible that two men could wrangle for hours in a courtroom and then shut off hostility at the moment of adjournment, like blowing out a lamp. He supposed his Anderson Avery was a good man, as lawyers went. At least he cost enough. But Claymore was not comfortable leaving his future in the hands of a man who had fought all his battles in the comfort of a courtroom, where the only blood he ever saw was in an opponent's eyes.

Anderson Avery mounted the hotel steps and asked politely if Claymore had enjoyed his dinner. Claymore only grunted. Special prosecuting attorney. Elihu Mallard looked past the old rancher, fastening his attention upon the screen door and passing through as quickly as he could.

Afraid of me, Claymore thought with satisfaction. Outside of the courtroom he ain't got the guts to look me in the eye.

Inside the hotel lobby Mallard declared, loudly enough for Claymore to hear, "Sheriff, than man out there is on trial for his life. Why do you not have him in custody?"

The sheriff's voice was touchy. "I got Willis keepin' an eye on him. Anyway, he ain't fixin' to run off. I don't believe that old man ever ran from anything."

Homer Whitcomb nursed a secret smile that often irritated Claymore almost to violence. For the twentieth time he made reference to the prosecutor's name. "Malard. Good handle for such a funny-lookin' duck."

To Homer, anyone outside the cattle-and-horse fraternity was peculiar.

Claymor grumped, "I've looked at better men over the sights of a rifle." The banked coals of courtroom anger stirred to a glow. "I wish it was still just the Indians. They faced you. These days you don't know who the enemy is half the time. They fight you with a pen instead of a gun."

He picked up the newspaper but could read only the Dallas masthead. He passed it to Homer. "You can still read without glasses. What does it say about me?"

"You don't want to hear all them lies."

Claymore demanded, "Read it!"

Reluctantly Homer folded the paper and held it almost at arm's length. He read slowly, stumbling now and again over an unfamiliar word as the article reviewed its version of Frank Claymore's spotted life. Claymore winced in pain when it touched upon the outlaw career of Billy Valentine. He interrupted Homer with an angry outburst. "Damn them, Homer! Damn them! Why can't they let Buily and all them other poor people just rest in peach?"

Homer shook his head and started to put the paper aside. Claymore motioned for him to continue reading. At length Homer came to a section that described Claymore as a greedy, evil old man, a despot of the range, a usurper of the children's grass. Homer looked up, reading the word again. "What's usurper mean?"

Claymore sighed. "I remember the stories they printed about me a long time ago. Said I was forgin' trails in the wilderness. Said I was turnin' them into highways and openin' the plains for civilization. I'm the same man. Old now, is all, instead of young. I was a hero then, Now I'm a greedy old despot. Where's the difference, Homer? I ain't changed."

Homer shook his head. "The world has changed."

Sheriff Ed Phelps walked out onto the porch, picking his teeth. He nodded civilly at Claymore but held his distance. Crowding forty, beginning to pack the first signs of tallow beneath his belt, he looked like a cattleman. Claymore felt more comfortable with him than the lawyers.

The deputy Willis motioned excitedly for the sheriff's attention. "Ed, I wisht you'd looky yonder. There's two Indians settin' under that big chinaberry tree."

Clay more said, "They're friends of mine."

The sheriff's eyebrow arched. "I thought you was an old Indian fighter."

Claymore frowned. "Used to be. Not anymore."

The deputy asked worriedly, "You want me to run them off, Ed"

Testily Claymore repeated. "They're friends of mine."

The sheriff pondered the two figures squatted in the tree's generous shade. "They look harmless to me."

Claymore saw a smile in Hormer's eyes. Harmless, he thought. Hell of a lot these people know. They just ain't old enough to remember.

Homer dropped the newspaper to the gray-painted gallery floor and stared wistfully off into the distance toward the open range, where the new spring grass was rising. Claymore hunched on the bench. He took out his watch, refusing to acknowledge the big clock in that hated cupola. He held the cane between his bony knees, tapping its tip against the toes of his foot-pinching black boots. Drowsiness came over him, for the trial had robbed him of his nap. He stared at the dreary courthouse, dreading his return to it. Gradually the dark stones seemed to dissolve before his half-closed eyes, and the town yielded to the open prairie. The years fell away from his weary shoulders, and in his mind he was again upon the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, where he had ridden so long ago with Homer and with others who were no but a fading memory...

* * *

Down from the rock-crested long hills into the broad valley of the Clear Fork the three horsemen had moved since dawn in a chill autumn mist, searching at first for their cattle, then watching in vain for a landmark to tell them where they were. The hills were brooding dark ghosts dimly seen through a blue-gray curtain drawn down by the season's first raw norther.

The sudden confrontation startled the Comanche hunting party as much as it surprised Frank Claymore and the two men who rode beside him. The riders reined up, stunned, facing each other across fifty yards of wet, brown-cured grass. Horses on both sides sensed the tension and danced nervously, wanting to run.

"My God!" declared George Valentine. "We're dead!"

Frank Claymore, barely the summer past twenty-two, felt as if the ground were opening up to engulf him. Shivering, he summoned the foresight to slip off the soft deerskin case that protected his long rifle from morning dampness. The Indians quickly spread out, widening their line. Frank had no idea whether this was a defensive move or preparation for a charge. He had never seen a hostile this near before. Ten-no, eleven. He looked expectantly at George Valentine for guidance. George, by a full three years his elder, captained the local flop-eared militia. But George trembled and offered no counsel.

Homer Whitcomb always had something to say whether it helped or not. "Them's Indians."

George asked plaintively, "What we goin' to do, Frank?"

Frank's first surge of fear made room for a little of annoyance. He was the youngest of the three. Why do they always look to me? He said, "You're the captain. You tell us."

But George Valentine gaped in shuddering silence at the Indians waving their weapons in challenge. He was ready to break and run.

Frank said, "Let's stand our ground." He tried to put more steel into his voice than he felt. "If we run they'll overtake us and kill us one by one."

George tugged on his reins. "We've got to try." His voice was unnaturally high-pitched. "Maybe our horses are faster."

Frank knew George's panic was about to infect Homer. He felt it himself. It would probably be fatal to them all. He reached deep for nerve. "We can't outrun them, not all of us. Let's get down slow. Show them we'll fight."

Homer Whitcomb dismounted first. He sighted his rifle across the saddle, the reins wrapped around his wrist. If firing started, Homer might not have the horse; the horse might have Homer. In the long run, Frank thought gravel, it probably would not matter.

He remained in the saddle, rifle leveled toward the Comanches, until George was down. Then Frank eased slowly to the ground, though an inner voice shrilled at him to hurry. The Indians shouted. Frank watched them with a mixture of dread and morbid fascination. He fought down an insistent fear, wondering which warrior carried the leadership. The Indians flung away the blankets they had worn against the chill. Frank saw no paint on their faces. He was vaguely disappointed, for their plainness did not live up to his expectations. But he saw color enough in the buffalo-hide shields they raised in taunting gestures and in the feathers and animal tails ornamenting the edges. He saw no firearms. All the warriors brandished bows. That was no firearms. All the warriors brandished much faster than the could fire and reload cap and ball.

George's voice was still strained. "One shot, then they'll be on us before we can reload. We'll have to bluff them."

Frank flared but did not speak the thought. If you know so damned much, why didn't you speak up before?

Homer Whitcomb was never too frightened to talk. "The one on the black horse acts like the leader...the one with the red shield that looks like blood spilled all over it."

Shortly that warrior rode out alone toward the three white men. Frank tensed, expecting the rush.

Rachal! he thought in dismay. Rachal may never know what happened to me.

The Comanche gestured with the crimson shield on his left arm and the bow in his right hand. His eyes fastened on Frank.

Homer said, "I believe he wants you to fight him."

The morning cold bit through Frank's soggy deerskin shirt. "I don't believe I want to do that." He looked at George, but George had nothing to offer.

Damn it, he thought, why should they always assume I am smarter, or stranger, or braver? But he recognized the dependency in the faces of George and Homer. Where he pointed, they would follow. If he panicked, so would they.

He studied the Indian and began as methodical a calculation as he could muster against a smothering fear. Frank was a good shot. Fatherless since ten, he had been sent into the woods by older brothers to fetch home meat while they tended crops. Far back east of here, on the Colorado River, Frank's rifle had often stood between the Claymores and hunger, for the land had been reluctant in its yield.

The Indian had only a bow, and arrows in a buckskin quiver on his shoulder.

It was not Frank's custom to call for help, not even from God. Prayer did not cross his mind. He said tightly, "Next time I may let you hunt cows by yourselves!"

Struggling against an instinct to cut and run, he left his brown horse and walked slowly into the middle ground where the challenging Indian waited. He had considered going mounted but reasoned that he could hold the long rifle steadier if he were on the ground. The Indian motioned for him to move closer. Twenty paces was as far as Frank would go. he held his breath while the Indian walked his horse toward him, shouting, gesturing with the feather-rimmed red shield. Frank could plainly see the dark round face. It struck him that the Comanche was no older than he. Perhaps his comrades had thrust this responsibility upon him as Frank's had done. Frank looked into the black eyes and thought he saw fear behind the bluster. Or perhaps he saw a mirroring of his own.

From a sheath at his waist the taunting warrior flourished a long, crude knife. Frank guessed he was being challenged to a duel with the steel, but the prospect of a knife chilled him. He held the rifle steady, pointing at a tiny rawhide bag hanging from the Indian's neck. At this close range he could not miss. But he knew the other Indians would kill him.

The warrior sheathed the knife, then whooped and drummed his heels into the black horse's ribs. While Frank stared in surprise, the Indian s...

The jarring strike of the clock in the towering cupola drew Frank Claymore's unwilling eyes to the two-story courthouse. It was a Texas-plains impression of some forbidding Old World castle in which monstrous crimes had been wrought upon the innocent. Claymore had opposed the construction of this gray-stone insult, just one of many fights lost as the years stole his strength and diminished his influence. His taxes, reluctantly paid, had gone far toward building that courthouse. Now he was being tried in it, and the wolves were at his gate.

A deputy sheriff slouched at one corner of the hotel's front porch, trying to be inconspicuous as he watched Frank Claymore with nervous, weasel eyes.

There ain't no job too low for somebody who don't want to work, Claymore thought darkly.

Muttering, he moved toward a bench, attacking the floor with his cane at every step. It was hard to come to a tolerance for this kind of attention. For a time now, until just lately, it had seemed that hardly anyone except Homer Whitcomb and the hired hands paid attention to him. Older people didn't count for much anymore. He muttered a bit louder, taking crude comfort from mule-skinner language that had always been therapeutic.

Homer was at his elbow. "You say somethin', Frank?" He took Claymore's arm and tried to help him toward the bench. "You just set yourself down. Be a spell yet before court takes up again. Yonder comes the prosecutin' attorney to dinner, him and that whole pack."

Claymore jerked his arm free of Homer Whitcomb's solicitous hands. "I can set myself, thank you." Instantly he regretted his irritability, but he knew he would react no differently the next time. Long years of struggle had etched a belligerent independence into his grain, as time had conditioned the gentle Homer Whitcomb to overlook such provocations and permit them to leave no track. It had long galled Claymore that Homer showed no evidence of rheumatism, of stiffened joints that ached in protest over every quick move. Homer's hair remained indecently dark, though he was by two years the older. But, then, he had never been run over by a herd of cattle, had never carried a flint arrowhead amongst his vitals.

Homer had what Claymore regarded as a hound-dog face, loose skinned and wonderfully pliable, falling easier into smile than frown, seeming usually to harbor some private joke that he savored like old wine. To Claymore, a man who bore so little worry on his shoulders was shirking his responsibilities.

Claymore pushed aside a newspaper he found lying in the way, then settled himself upon the center of the bench so no one could share it with him. He glanced about with his eyes fierce in challenge of anyone who might have the temerity to try.

Homer asked, "Anything I can bring you, Frank?"

"I just had dinner. What the hell could I want?"

Homer seated himself in a nearby chair, showing no reaction. He was more than a working partner; he was a friend from far back down the long years. Like Frank Claymore, he had always done as he damn well pleased, and it had never pleased him to acknowledge the unpleasant.

Claymore studied the business-suited men passing through the gate of the white picket fence that surround the court-house square, picking their way among the tied horses, the wagons and buggies. His vision was still sharp when he looked into the distance. He could see the special prosecuting attorney and his own lawyer walking side by side, conversing pleasantly, apparently the best of friends.

Claymore muttered again. When a man worked for you and accepted your pay, your enemies ought to be his enemies.

He did not understand lawyers. He did not understand anybody who spent his days sheltered beneath a roof, dealing in intangibles such as law or accounts receivable rather than something solid and real like cattle and horses. It was incomprehensible that two men could wrangle for hours in a courtroom and then shut off hostility at the moment of adjournment, like blowing out a lamp. He supposed his Anderson Avery was a good man, as lawyers went. At least he cost enough. But Claymore was not comfortable leaving his future in the hands of a man who had fought all his battles in the comfort of a courtroom, where the only blood he ever saw was in an opponent's eyes.

Anderson Avery mounted the hotel steps and asked politely if Claymore had enjoyed his dinner. Claymore only grunted. Special prosecuting attorney. Elihu Mallard looked past the old rancher, fastening his attention upon the screen door and passing through as quickly as he could.

Afraid of me, Claymore thought with satisfaction. Outside of the courtroom he ain't got the guts to look me in the eye.

Inside the hotel lobby Mallard declared, loudly enough for Claymore to hear, "Sheriff, than man out there is on trial for his life. Why do you not have him in custody?"

The sheriff's voice was touchy. "I got Willis keepin' an eye on him. Anyway, he ain't fixin' to run off. I don't believe that old man ever ran from anything."

Homer Whitcomb nursed a secret smile that often irritated Claymore almost to violence. For the twentieth time he made reference to the prosecutor's name. "Malard. Good handle for such a funny-lookin' duck."

To Homer, anyone outside the cattle-and-horse fraternity was peculiar.

Claymor grumped, "I've looked at better men over the sights of a rifle." The banked coals of courtroom anger stirred to a glow. "I wish it was still just the Indians. They faced you. These days you don't know who the enemy is half the time. They fight you with a pen instead of a gun."

He picked up the newspaper but could read only the Dallas masthead. He passed it to Homer. "You can still read without glasses. What does it say about me?"

"You don't want to hear all them lies."

Claymore demanded, "Read it!"

Reluctantly Homer folded the paper and held it almost at arm's length. He read slowly, stumbling now and again over an unfamiliar word as the article reviewed its version of Frank Claymore's spotted life. Claymore winced in pain when it touched upon the outlaw career of Billy Valentine. He interrupted Homer with an angry outburst. "Damn them, Homer! Damn them! Why can't they let Buily and all them other poor people just rest in peach?"

Homer shook his head and started to put the paper aside. Claymore motioned for him to continue reading. At length Homer came to a section that described Claymore as a greedy, evil old man, a despot of the range, a usurper of the children's grass. Homer looked up, reading the word again. "What's usurper mean?"

Claymore sighed. "I remember the stories they printed about me a long time ago. Said I was forgin' trails in the wilderness. Said I was turnin' them into highways and openin' the plains for civilization. I'm the same man. Old now, is all, instead of young. I was a hero then, Now I'm a greedy old despot. Where's the difference, Homer? I ain't changed."

Homer shook his head. "The world has changed."

Sheriff Ed Phelps walked out onto the porch, picking his teeth. He nodded civilly at Claymore but held his distance. Crowding forty, beginning to pack the first signs of tallow beneath his belt, he looked like a cattleman. Claymore felt more comfortable with him than the lawyers.

The deputy Willis motioned excitedly for the sheriff's attention. "Ed, I wisht you'd looky yonder. There's two Indians settin' under that big chinaberry tree."

Clay more said, "They're friends of mine."

The sheriff's eyebrow arched. "I thought you was an old Indian fighter."

Claymore frowned. "Used to be. Not anymore."

The deputy asked worriedly, "You want me to run them off, Ed"

Testily Claymore repeated. "They're friends of mine."

The sheriff pondered the two figures squatted in the tree's generous shade. "They look harmless to me."

Claymore saw a smile in Hormer's eyes. Harmless, he thought. Hell of a lot these people know. They just ain't old enough to remember.

Homer dropped the newspaper to the gray-painted gallery floor and stared wistfully off into the distance toward the open range, where the new spring grass was rising. Claymore hunched on the bench. He took out his watch, refusing to acknowledge the big clock in that hated cupola. He held the cane between his bony knees, tapping its tip against the toes of his foot-pinching black boots. Drowsiness came over him, for the trial had robbed him of his nap. He stared at the dreary courthouse, dreading his return to it. Gradually the dark stones seemed to dissolve before his half-closed eyes, and the town yielded to the open prairie. The years fell away from his weary shoulders, and in his mind he was again upon the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, where he had ridden so long ago with Homer and with others who were no but a fading memory...

* * *

Down from the rock-crested long hills into the broad valley of the Clear Fork the three horsemen had moved since dawn in a chill autumn mist, searching at first for their cattle, then watching in vain for a landmark to tell them where they were. The hills were brooding dark ghosts dimly seen through a blue-gray curtain drawn down by the season's first raw norther.

The sudden confrontation startled the Comanche hunting party as much as it surprised Frank Claymore and the two men who rode beside him. The riders reined up, stunned, facing each other across fifty yards of wet, brown-cured grass. Horses on both sides sensed the tension and danced nervously, wanting to run.

"My God!" declared George Valentine. "We're dead!"

Frank Claymore, barely the summer past twenty-two, felt as if the ground were opening up to engulf him. Shivering, he summoned the foresight to slip off the soft deerskin case that protected his long rifle from morning dampness. The Indians quickly spread out, widening their line. Frank had no idea whether this was a defensive move or preparation for a charge. He had never seen a hostile this near before. Ten-no, eleven. He looked expectantly at George Valentine for guidance. George, by a full three years his elder, captained the local flop-eared militia. But George trembled and offered no counsel.

Homer Whitcomb always had something to say whether it helped or not. "Them's Indians."

George asked plaintively, "What we goin' to do, Frank?"

Frank's first surge of fear made room for a little of annoyance. He was the youngest of the three. Why do they always look to me? He said, "You're the captain. You tell us."

But George Valentine gaped in shuddering silence at the Indians waving their weapons in challenge. He was ready to break and run.

Frank said, "Let's stand our ground." He tried to put more steel into his voice than he felt. "If we run they'll overtake us and kill us one by one."

George tugged on his reins. "We've got to try." His voice was unnaturally high-pitched. "Maybe our horses are faster."

Frank knew George's panic was about to infect Homer. He felt it himself. It would probably be fatal to them all. He reached deep for nerve. "We can't outrun them, not all of us. Let's get down slow. Show them we'll fight."

Homer Whitcomb dismounted first. He sighted his rifle across the saddle, the reins wrapped around his wrist. If firing started, Homer might not have the horse; the horse might have Homer. In the long run, Frank thought gravel, it probably would not matter.

He remained in the saddle, rifle leveled toward the Comanches, until George was down. Then Frank eased slowly to the ground, though an inner voice shrilled at him to hurry. The Indians shouted. Frank watched them with a mixture of dread and morbid fascination. He fought down an insistent fear, wondering which warrior carried the leadership. The Indians flung away the blankets they had worn against the chill. Frank saw no paint on their faces. He was vaguely disappointed, for their plainness did not live up to his expectations. But he saw color enough in the buffalo-hide shields they raised in taunting gestures and in the feathers and animal tails ornamenting the edges. He saw no firearms. All the warriors brandished bows. That was no firearms. All the warriors brandished much faster than the could fire and reload cap and ball.

George's voice was still strained. "One shot, then they'll be on us before we can reload. We'll have to bluff them."

Frank flared but did not speak the thought. If you know so damned much, why didn't you speak up before?

Homer Whitcomb was never too frightened to talk. "The one on the black horse acts like the leader...the one with the red shield that looks like blood spilled all over it."

Shortly that warrior rode out alone toward the three white men. Frank tensed, expecting the rush.

Rachal! he thought in dismay. Rachal may never know what happened to me.

The Comanche gestured with the crimson shield on his left arm and the bow in his right hand. His eyes fastened on Frank.

Homer said, "I believe he wants you to fight him."

The morning cold bit through Frank's soggy deerskin shirt. "I don't believe I want to do that." He looked at George, but George had nothing to offer.

Damn it, he thought, why should they always assume I am smarter, or stranger, or braver? But he recognized the dependency in the faces of George and Homer. Where he pointed, they would follow. If he panicked, so would they.

He studied the Indian and began as methodical a calculation as he could muster against a smothering fear. Frank was a good shot. Fatherless since ten, he had been sent into the woods by older brothers to fetch home meat while they tended crops. Far back east of here, on the Colorado River, Frank's rifle had often stood between the Claymores and hunger, for the land had been reluctant in its yield.

The Indian had only a bow, and arrows in a buckskin quiver on his shoulder.

It was not Frank's custom to call for help, not even from God. Prayer did not cross his mind. He said tightly, "Next time I may let you hunt cows by yourselves!"

Struggling against an instinct to cut and run, he left his brown horse and walked slowly into the middle ground where the challenging Indian waited. He had considered going mounted but reasoned that he could hold the long rifle steadier if he were on the ground. The Indian motioned for him to move closer. Twenty paces was as far as Frank would go. he held his breath while the Indian walked his horse toward him, shouting, gesturing with the feather-rimmed red shield. Frank could plainly see the dark round face. It struck him that the Comanche was no older than he. Perhaps his comrades had thrust this responsibility upon him as Frank's had done. Frank looked into the black eyes and thought he saw fear behind the bluster. Or perhaps he saw a mirroring of his own.

From a sheath at his waist the taunting warrior flourished a long, crude knife. Frank guessed he was being challenged to a duel with the steel, but the prospect of a knife chilled him. He held the rifle steady, pointing at a tiny rawhide bag hanging from the Indian's neck. At this close range he could not miss. But he knew the other Indians would kill him.

The warrior sheathed the knife, then whooped and drummed his heels into the black horse's ribs. While Frank stared in surprise, the Indian s...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTexas Christian University Press

- Publication date1990

- ISBN 10 0875650430

- ISBN 13 9780875650432

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages285

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 253.36

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Stand Proud (Texas Tradition (Hardcover))

Published by

Texas Christian University Press

(1990)

ISBN 10: 0875650430

ISBN 13: 9780875650432

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0875650430

Buy New

US$ 253.36

Convert currency