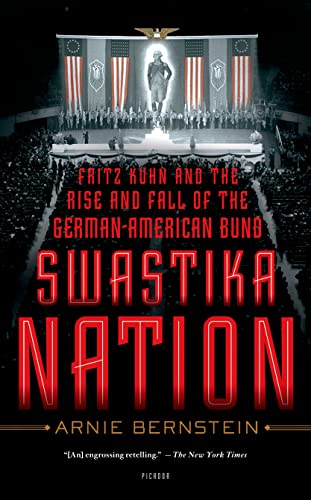

Items related to Swastika Nation

Imagine a United States where swastikas hang proudly in meeting rooms across the country. Cries of Sieg Heil! resound at rural family retreats. A dictator pontificates at Madison Square Garden to an overflowing crowd for a Nuremberg-style rally.

This is not alternative historical fiction; this is the true story of the German-American Bund. In the late 1930s, the Bund, led by Fritz Kuhn, was a small but powerful national movement, determined to conquer the U.S. government with a fascist dictatorship. However, the Bundist dream of a swastika nation attracted powerful foes. Many larger-than-life figures―including New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia; the newly formed Congressional House Committee on Un-American Activities; newspaper columnist Walter Winchell; and Jewish mobsters Meyer Lansky and Mickey Cohen―brought Kuhn and the German-American Bund to an inglorious end.

Arnie Bernstein's Swastika Nation is a story of bad guys, good guys, and a few guys in between. The rise and fall of Fritz Kuhn and his German-American Bund is a sometimes funny, sometimes harrowing, always compelling story from start to finish, a vibrant narrative of a forgotten corner of American history.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Fritz Julius Kuhn

ON THE EVENING OF November 8, 1923, three thousand men packed the Bürgerbräukeller, a beer hall in Munich, Germany, waiting to hear a speech by Gustav Ritter von Kahr, the controversial leader of Bavaria’s chaotic postwar government. Outside, where a uniformed and adversarial mix of stormtroopers and police uneasily mixed, it was wet and cold. Inside the hall was a choking miasma of stale smoke, beer, and sweat.

A foppish man outfitted with a Charlie Chaplin toothbrush mustache sat nervously at the bar and ordered three beers. In the wake of Germany’s crippling postwar recession the price was hard: one billion marks per glass.1

Austrian by birth, German by choice, Adolf Hitler was a failed art student and veteran of the Great War; a brooder overflowing with ideas and prepared for action. It was time to live up to his name “Adolf,” an old Teutonic word meaning “fortunate wolf.”2 Tonight, within the packed confines of a Munich beer hall, this fortunate wolf felt poised to change the world. The dismal late autumn weather had compounded a daylong headache. What’s more, his jaw throbbed from an ugly toothache. “See a dentist,” his friends had implored, but Hitler had paid them no mind. There was work to be done, work of national importance—nay, world importance. His physical maladies were nothing compared to the rot pervading his adopted country.3

As Kahr outlined the aims of his government, a colleague approached Hitler at the bar. The time was now.

Hitler whipsawed one of the billion-mark beers to the floor, smashing the mug with a loud crash. Pulling his Browning pistol from its holster Hitler, surrounded by a thug entourage pushing and elbowing bewildered inebriates out of the way, defiantly took the stage. Hitler held his pistol high, squeezed the trigger, and sent a bullet into the ceiling.

The Browning’s loud bang! did the trick. The confused and rambunctious crowd fell into uneasy silence, a moment that lasted all of an eye blink. From outside storm troopers poured into the packed hall, crying “ Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler!” It was a dictum more than a salute, barked out by loyalists to a cause greater than themselves.4

“The national revolution has broken out!” Hitler declared. “The hall is surrounded!”5

History would remember this night as the “Beer Hall Putsch,” Hitler’s attempt to seize the government for Nazi control. Though the night ended in failure with Hitler’s arrest, it marked the beginning for a nascent movement that grew into a New World Order the fortunate wolf dreamed of: Germany’s conquering Third Reich.

As the cult of Hitler expanded over the years, many of his acolytes would proudly say, “I was at Bürgerbräukeller. I stood with our führer from the start.” Among those who declared he boldly followed the future dictator into the melee was a plump, nearsighted chemist named Fritz Julius Kuhn.6 In the end, it didn’t really matter whether or not Kuhn was part of the putsch mob. Throughout his life, he would claim many things.

* * *

Fritz Julius Kuhn was born on May 15, 1896, in Munich to Karl and Anna Kuhn.7 The Kuhns raised a large brood; Fritz was one of Karl and Anna’s twelve children.8 His childhood was nondescript at best. Certainly nothing emerged in later investigations of Kuhn’s past that would show any glimmer of what he was to become.

In 1913, during Kuhn’s high school years, Hitler moved to Munich from Vienna. He was twenty-four, a failed art student with a dismal future and completely taken with his new surroundings. “A German city!” he later rhapsodized in his autobiography/manifesto Mein Kampf. “[T]here was … heartfelt love which seized me for this city more than any other place that I knew, almost from the first hour of my sojourn there.”9 Munich provided fertile ground for Hitler’s growing Jewcentric ideologies. This “German city” was teeming with anti-Semitic salons and Hitler soaked it in.10 He plunged himself into studies, while eking out a meager living selling architectural drawings to afford the tiny room where he lived. After long days of creating art and voraciously devouring book upon book, Hitler would head to beer halls for the always lively, sometimes drunken political discussions hurled back and forth on any given night.11 In some quarters, a greeting was traded between friends to indicate their anti-Semitic political bonds. It was a simple but effective word: Heil!12

* * *

On June 28, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie paraded in an open car through the streets of Sarajevo. The pleasingly plump couple seemed not to have a care in the world as they soaked in the cheers of a mostly adoring crowd lining the streets. Yet among the happy faces were some stern looks, silently holding in their contempt for the royal pomposity.

Lurking within the crowd, slipping in and out of the throng, five teenagers all wracked by tuberculosis tightly held their coats, guarding secrets. The minutes dragged until one of the young men saw his chance. He hurled a pocket-sized explosive at the archduke’s car. Evasive moves by Ferdinand’s sharp-eyed driver couldn’t stop the bomb from landing in the automobile. Quickly realizing what was happening, the archduke threw up his arm to shield Sophie from the incoming firepower. His actions had limited effect; shrapnel from the explosion cut her slightly along the neck. The chauffeur floored the gas pedal, smashed cars, and injured pedestrians in the confusion.

Not ones to let an assassination attempt ruin the day, Ferdinand and Sophie next attended a mayoral welcoming ceremony at Sarajevo’s city hall. After the ritual pomp and circumstance, the archduke insisted on going to the hospital to meet people hit by his car during the royal getaway.

Apparently the change in plans confused the chauffer. He drove down the scheduled motorcade route but was corrected on his mistake and told to change direction.

The car stopped. Five feet away, Gavrilo Princip saw his chance.

Princip, the brains of the tubercular quintet, pulled a handgun from his coat and squeezed off two shots. Ferdinand, the intended target, was neatly hit. The second bullet penetrated the car door, then struck Sophie. Seconds after pulling the trigger the assassin tried to turn the gun on himself. A mob grabbed him, deflecting any chance for Princip to commit suicide. His second option, chomping down on a vial of cyanide, was an equal failure. The poison within was old, its lethal potency long evaporated.13

Princip’s bullets cut down two people. The war sparked by this assassination ultimately would kill millions, military and civilian alike.

* * *

One month to the day after Ferdinand’s assassination, Austria-Hungry declared war on Serbia. Four days later, on August first, Hitler joined the exuberant crowd in Odeonsplatz, Munich’s central square, celebrating Germany’s declaration of war on France and Russia.14

Like Hitler, and so many young men of his generation, eighteen-year-old Fritz Kuhn volunteered in the fight for his country. Joining a Bavarian combat unit, Kuhn developed adept skills as a machine gunner, providing firepower support to brethren in the war-torn trenches of France.15 He served four years, rising to the rank of lieutenant. For bravery on the field of battle Kuhn was awarded the Iron Cross First Class, the German military’s highest honor. It surely was a proud moment, as this esteemed laurel was rarely bestowed on enlisted men.16 And in this award, Kuhn’s life invisibly crossed Hitler’s, another enlisted man who earned the coveted medal.17

Luster ultimately dimmed in the wake of German defeat in the Great War. The devastating loss was followed by the Treaty of Versailles, a forced contract on Germany from the American, French, and English victors demanding reparations be paid from a people shattered by postwar economic recession.

With no job and no future in sight, Kuhn joined many disillusioned veterans in the Freikorps, a paramilitary force determined to restore honor to the Fatherland. These freelance troops were funded surreptitiously with money funneled into an anti-Bolshevik movement by leaders of German heavy industry, including Alfred Krupp, Emil Kirdorf, Hugo Stinnes, Albert Vögler, and Hermann Röchling. The country may have been in turmoil and deep in an overwhelming recession, but the barons of business were taking no chances that upstart rebels might cut into their profits via revolution.18 Freikorps volunteers, still bitter from Germany’s loss, were lured by patriotic broadsides and newspaper advertisements, crying out for men to defend honor of country and “prevent Germany from becoming the laughingstock of the earth.”19

They operated under the eye of Gustav Noske, Germany’s postwar Minister of Defense. In the terrible wake of Germany’s humiliation in the Great War, the Freikorps served as a sort of internal protection force. Their law enforcement techniques were highly unorthodox, driven by a mob psychology specializing in intimidation and brutality.20

The bankrollers behind Freikorps had reason to worry. The Spartacus League, a leftist force that took its name from the leader of the ancient Greek slave revolt, was making inroads. Under the leadership of Rosa Luxemburg—a Jewish Russian–born Marxist—and her colleague, fiery German attorney Karl Liebknecht, a Bolshevik takeover similar to the recent Russian revolution loomed. The Spartacist movement was gaining momentum in Berlin, taking control of public utilities, transportation, and munitions factories. Friedrich Ebert, the postwar German Republic’s first president, panicked. He fired Berlin’s chief of police, declaring the man a Spartacist sympathizer.21

On Sunday, January 5, 1919, Spartacists held rallies and demonstrations throughout the streets of Berlin. Luxemburg issued a broadsheet imploring people throughout Germany to join the fight. “Act! Act! Courageously, consistently—that is the ‘accursed’ duty and obligation…” she wrote. “Disarm the counter-revolution. Arm the masses. Occupy all positions of power. Act quickly!”

Overthrow of the government was quelled through efficient and merciless means.

During what became known as “Bloody Week,” Freikorps volunteers from throughout the country flocked to Berlin. Forces amplified to thousands of men salivating for street battles against the paltry opposition.

Using an abandoned school as his headquarters, Noske took command as Freikorps men brought down wave upon wave of the enemy throughout the week. On January 11, Freikorps shock troops, armed with flamethrowers and machine guns, unleashed their furies on the headquarters of the leftist newspaper Vorwärts. Spartacist snipers scattered throughout the building held out as best they could. Finally seven of the rebels came out waving white handkerchiefs. One member of the group was sent back into the building, with the message that Freikorps would only accept unconditional surrender. The remaining six were beaten and shot. As they fell into gruesome heaps, three hundred remaining Spartacists inside the building were rounded up. Seven people in this final group were turned into helpless targets, blasted with a fusillade of ammunition as their comrades were taken into custody en masse.

Next were Luxemburg and Liebknecht. The duo, holed up in the flat of one of Liebknecht’s relatives, was found on January 15th. They were hauled to the ironically named Hotel Eden in the center of Berlin. Liebknecht was clubbed insensible with rifle butts.22 Battered and helpless, he was dragged off to nearby Tiergarten, a public greenery described by author Erik Larson as “… Berlin’s equivalent to Central Park. The name, in literal translation, meant ‘animal garden’ or ‘garden of the beasts…’”23 Liebknecht was ordered to walk. As he stumbled forward Freikorps guns riddled his back with bullets. The bloodied corpse was dumped off at the Berlin Zoo like a slab of freshly butchered meat meant for animal feed.24

Once Liebknecht was dispatched attentions turned to Luxemburg. Like her now-dead comrade, she was slammed in the skull with merciless rifle butts. Bleeding from her nose and mouth, unconscious yet still alive, she was thrown into a car and spirited away. Hotel workers heard pistol shots as the automobile peeled off.25 Upon reaching Berlin’s Landwehr Canal, Luxemburg’s killers secured heavy stones around her body with tightly bound wire, and then threw the weighted corpse into the water. “The old slut is swimming now,” sneered one of the assassins.26 Five months later Luxemburg’s remains, a bloated caricature of a woman, were found in one of the canal locks.27

Emboldened by the unchecked Berlin slaughter, men throughout the country clamored to join Freikorps. Kuhn signed on with a unit organized by Colonel Franz Ritter von Epp, a highly decorated hero of Germany’s doomed war efforts.28 The division—known as Freikorps Epp—was formed in the violent wake of Bloody Week. Its members were mostly former enlisted men such as Kuhn and became the largest Freikorps regiment in Bavaria.29 Determined not to let any rebels create new threats, Kuhn and his fellow soldiers in the Freikorps Epp kept tight and brutal rings surrounding cities throughout the region. “No pardon is given,” one member of the group wrote. “We shoot even the wounded.… Anyone who falls into our hands first gets the rifle butt and then is finished off with a bullet. We even shot ten Red Cross nurses on sight because they were carrying pistols. We shot those little ladies with pleasure—how they cried and pleaded with us to save their lives. Nothing doing! Anyone with a gun is our enemy…”30

Like many of his Freikorps volunteers, Kuhn joined Hitler’s growing Nazi Party, officially becoming a member in 1921. Intellectual ambition separated him from the majority of his peers, most of whom were working class men of limited schooling. Kuhn enrolled in the University of Munich and in 1922 earned the American equivalent of a master’s degree in chemical engineering.31

Higher education afforded Kuhn opportunities outside the classroom. He developed a penchant for pilfering the overcoats of fellow students, a crime that earned Kuhn four months at Munich’s Stadelheim Prison in 1921.32 Again, Kuhn and Hitler crossed inadvertent paths. On April 16, 1922, Hitler was arrested and taken to Stadelheim for inciting an Easter Sunday riot, shouting, “Two thousand years ago, the mob of Jerusalem dragged a man to execution in just this way!”33

Fearful for his son’s future, Karl Kuhn sought out Reinhold Spitz, a Jewish manufacturer whose clothing factory was down the street from Kuhn’s business. Spitz empathized with the situation, having known Fritz since he was four years old, and in 1924 hired the wayward young man as a shipping clerk.34

Within a few months Spitz noticed that bolts of cloth used in factory machinery were coming up short. On further investigation, he realized the actual lengths of cloth were not as stated on inventory tags. Spitz’s first thought was that his suppliers were cheating him, but this proved wrong. Next he traced how the cloth bolts were transported within his factory. Somewhere between the first-floor stock room and the third-floor manufacturing plant on the top of the building, an employee was altering inventory. Watching carefully through a workroom door, Spitz found his culprit. Fritz Kuhn was using tailor’s shear...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPicador

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1250056012

- ISBN 13 9781250056016

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Swastika Nation

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks368190

Swastika Nation

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB1250056012