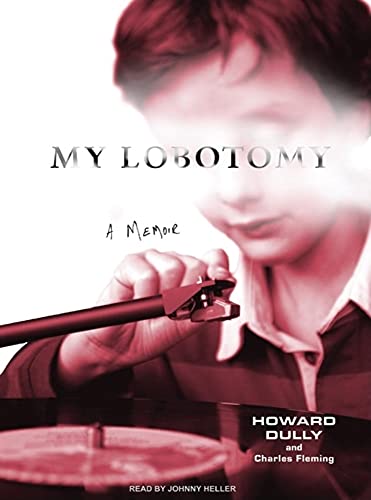

Items related to My Lobotomy: A Memoir

A gut-wrenching memoir by a man who was lobotomized at the age of twelve.

Assisted by journalist/novelist Charles Fleming, Howard Dully recounts a family tragedy whose Sophoclean proportions he could only sketch in his powerful 2005 broadcast on NPR's All Things Considered.

"In 1960," he writes, "I was given a transorbital, or 'ice pick' lobotomy. My stepmother arranged it. My father agreed to it. Dr. Walter Freeman, the father of the American lobotomy, told me he was going to do some 'tests.' It took ten minutes and cost two hundred dollars." Fellow doctors called Freeman's technique barbaric: an ice pick-like instrument was inserted about three inches into each eye socket and twirled to sever connections from the frontal lobe to the rest of the brain. The procedure was intended to help curb a variety of psychoses by muting emotional responses, but sometimes it irreversibly reduced patients to a childlike state or (in 15 percent of the operations Freeman performed) killed them outright. Dully's ten-minute "test" did neither, but in some ways it had a far crueler result, since it didn't end the unruly behavior that had set his stepmother against him to begin with.

"I spent the next forty years in and out of insane asylums, jails, and halfway houses," he tells us. "I was homeless, alcoholic, and drug-addicted. I was lost." From all accounts, there was no excuse for the lobotomy. Dully had never been "crazy," and his (not very) bad behavior sounds like the typical acting-up of a child in desperate need of affection. His stepmother responded with unrelenting abuse and neglect, and his father allowed her to demonize his son and never admitted his complicity in the lobotomy; Freeman capitalized on their monumental dysfunction. It's a tale of epic horror, and while Dully's courage in telling it inspires awe, listeners are left to speculate about what drove supposedly responsible adults to such unconscionable acts.

Assisted by journalist/novelist Charles Fleming, Howard Dully recounts a family tragedy whose Sophoclean proportions he could only sketch in his powerful 2005 broadcast on NPR's All Things Considered.

"In 1960," he writes, "I was given a transorbital, or 'ice pick' lobotomy. My stepmother arranged it. My father agreed to it. Dr. Walter Freeman, the father of the American lobotomy, told me he was going to do some 'tests.' It took ten minutes and cost two hundred dollars." Fellow doctors called Freeman's technique barbaric: an ice pick-like instrument was inserted about three inches into each eye socket and twirled to sever connections from the frontal lobe to the rest of the brain. The procedure was intended to help curb a variety of psychoses by muting emotional responses, but sometimes it irreversibly reduced patients to a childlike state or (in 15 percent of the operations Freeman performed) killed them outright. Dully's ten-minute "test" did neither, but in some ways it had a far crueler result, since it didn't end the unruly behavior that had set his stepmother against him to begin with.

"I spent the next forty years in and out of insane asylums, jails, and halfway houses," he tells us. "I was homeless, alcoholic, and drug-addicted. I was lost." From all accounts, there was no excuse for the lobotomy. Dully had never been "crazy," and his (not very) bad behavior sounds like the typical acting-up of a child in desperate need of affection. His stepmother responded with unrelenting abuse and neglect, and his father allowed her to demonize his son and never admitted his complicity in the lobotomy; Freeman capitalized on their monumental dysfunction. It's a tale of epic horror, and while Dully's courage in telling it inspires awe, listeners are left to speculate about what drove supposedly responsible adults to such unconscionable acts.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

At twelve years old, Howard Dully was one of the youngest patients to receive an "ice pick" lobotomy.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chapter 1

June

This much I know for sure: I was born in Peralta Hospital in Oakland, California, on November 30, 1948. My parents were Rodney Lloyd Dully and June Louise Pierce Dully. I was their first child, and they named me Howard August Dully, after my father’s father. Rodney was twenty-three. June was thirty-four.

They had been married less than a year. Their wedding was held on Sunday, December 28, 1947, three days after Christmas, at one o’clock in the afternoon, at the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Sacramento, California. The wedding photographs show an eager, nervous couple. He’s in white tie and tails, with a white carnation in his lapel. She’s in white satin, and a veil decorated with white flowers. They are both dark-haired and dark-eyed. Together they are cutting the cake—staring at the cake, not at each other—and smiling.

A reception followed at 917 Forty-fifth Street, at the home of my mother’s uncle Ross and aunt Ruth Pierce. My father’s mother attended. So did his two brothers. One of them, his younger brother, Kenneth, wore a tuxedo all the way up from San Jose on the train.

My father’s relatives were railroad workers and lumberjack types from the area around Chehalis and Centralia, Washington. My dad spent his summers in a lumber camp with one of his uncles. They were logging people.

My father’s father was an immigrant, born in 1899 in a place called Revel, Estonia, in what would later be the Soviet Union. When he left Estonia, his name was August Tulle. When he got to America, where he joined his brothers, Alexander and John— he had two sisters, Marja and Lovisa, whom he left behind in Estonia—he was called August Dully. He later added the first name Howard, because it sounded American to him.

My father’s mother was the child of immigrants from Ireland. She was born Beulah Belle Cowan in Litchfield, Michigan, in 1902. Her family later moved to Portland, Oregon, in time for Beulah to attend high school, where she was so smart she skipped two grades.

August went to Portland, too, because that’s where his brothers were. According to his World War I draft registration card, he was brown-haired, blue-eyed, and of medium height. He got work as a window dresser for the Columbia River Ship Company. He became a mason. He met the redheaded Beulah at a dance. She told her mother that night, “I just met the man I’m going to marry.” She was sixteen. A short while later, they tied the knot and took a freighter to San Francisco for their honeymoon, and stayed. A 1920 U.S. Census survey shows them living in an apartment building on Fourth Street. Howard A. Dully was now a naturalized citizen, working as a laborer in the shipyards.

Sometime after, they moved to Washington, where my grandfather went to work on the railroads. They started having sons—Eugene, Rodney, and Kenneth—before August got sick with tuberculosis. Beulah believed he caught it on that freighter going to San Francisco. He died at home, in bed, on New Year’s Day, 1929. My dad was three years old. His baby brother was only fourteen months old.

Beulah Belle never remarried. She was hardheaded and strong-willed. She said, “I will never again have a man tell me what to do.”

But she had a hard time taking care of her family. She couldn’t keep up payments on the house. When she lost it, the boys went to stay with relatives. My dad was sent to live with an aunt and uncle at age six, and was shuffled from place to place after that. By his own account, he lived in six different cities before he finished high school—born in Centralia, Washington; then shipped around Oregon to Marshfield, Grants Pass, Medford, and Eugene; then to Ryderwood, Washington, where he and his brother Kenneth lived in a logging camp with their former housekeeper Evelyn Townsend and her husband, Orville Black.

At eighteen, Rod left Washington to serve with the U.S. Army, enlisting in San Francisco on December 9, 1943. Though he later was reluctant to talk about it, I know from my uncles that he was sent overseas and stationed in France. He served with the 723rd Railroad Division, laying track in an area near L’Aigle, France, that was surrounded by mines. One of my uncles told me that my father never recovered from the war. He said, “The man who went away to France never came back. He was damaged by what he saw there.”

But another of my uncles told me Rod bragged about having a German girlfriend, so I guess it wasn’t all bad. Not as bad as his brother Gene, who joined the army and got sent to Australia and New Guinea, where he developed malaria and tuberculosis and almost died. He weighed one hundred pounds when he came back to America, and lived at a military hospital in Livermore, California, for a long time after that.

By the time Rod finished his military service, his mother had left her job with Western Union Telegraph, in the Northwest, and moved to Oakland to work for the Southern Pacific Railroad. She was later made a night supervisor, working in the San Francisco office on Market Street. She would still be working there when I was born.

My mother’s folks came from the other end of the economic spectrum. June was the daughter of Daisy Seulberger and Hubert O. Pierce—German on her mother’s side, English on her father’s. Daisy grew up weatlthy, married Pierce, and had three children: Gordon, June, and Hugh. When Pierce died, Daisy married Delos Patrician, another wealthy Bay Area businessman. She moved her family to Oakland, into a huge, three-story shingled home on Newton Avenue. June spent her childhood there.

After his military service, my father relocated to the Bay Area and started taking classes at San Francisco Junior College, learning to be a teacher and doing his undergraduate work in elementary education.

Over the summers, he got part-time work at a popular high Sierras vacation spot, Tuolumne Meadows, in Yosemite. He met a young woman there, working as a housekeeper, who captured his eye. Her name was June.

She was tall, dark, and athletic, and for Rod she was a real catch. She was a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, where she had been active with the Alpha Xi Delta sorority, and had a certificate to teach nursery school. She was from a well-known Oakland family, and for several years she had been a fixture on the local social scene. During the war she had worked in Washington, D.C., as a private secretary to the U.S. congressman from her district. When she returned to Oakland, she often had her name in the newspapers, hosting luncheons and teas for her society friends.

She had been courted by quite a few young men, but her controlling mother, Daisy, drove all the boyfriends away. When she met Rod, June was still beautiful, but she was no longer what you’d call young, especially not at that time. She was thirty-two. Being unmarried at that age during the 1940s was almost like being a spinster.

Their courtship was sudden and passionate. They fell in love over the summer of 1946, and saw each other in San Francisco and Berkeley through the next year. When June returned to work in Yosemite in the summer of ’47, this time at Glen Aulin Camp, Rod left for the lumberyards of northern California and southern Oregon, where he was determined to make enough money to marry June in style. His letters over that summer were eager and filled with love. He was full of plans and promises—for his career, their wedding, the house he would buy her, the family they would have. He was worried that he was not the man June’s mother wanted, or from the right level of society, but he was determined to prove himself. “I expect to make you happy. I won’t marry you and take you into a life you won’t be happy in,” he wrote. “I’m happy now, much happier than I’ve ever been before in my life, cause you’re my little dream girl and my dream is coming true.”

After a hard summer of logging work, the plans for the wedding were made. The ceremony was held three days after Christmas in Sacramento. According to a newspaper story a week later, the couple was “honeymooning in Carmel” after a ceremony in which “the bride wore a white satin gown with a sweetheart neckline, long sleeves ending in points at the wrists and full skirt with a double peplum pointed at the front. Her full-length veil of silk net was attached to a bandeau of seed pearls and orange blossoms. She also carried a handkerchief which has been in her family for 75 years.”

The bride was given away by her uncle Ross, in whose Sacramento house she had been living. The groom’s best man was his brother Kenneth.

According to family stories, some of June’s family objected. Rod was too young for June, Daisy said, and didn’t have good prospects. June may have been uncomfortable with the relative poverty she was marrying into, too. My dad later told people that he got into a fender bender not long after he met June, and that his feelings were hurt when she said she was embarrassed to be seen driving around in his banged-up car.

With a wife to support, my father left school. He and my mother moved up north, to Medford, Oregon, where Rod returned to the lumber business and went to work as a lumber tallyman with the Southern Oregon Sugar Pine Corporation in Central Point, two miles outside of Medford.

Soon the young married couple had a baby on the way—me. Near the end of her term, my mother left my dad in Medford and moved in with her mother in Oakland, a pattern she would repeat for the births of all her children.

If everything had gone as planned, she probably would have returned to Medford and raised a family.

But my father had some bad luck. One morning on a work break he became incoherent and had to be taken by ambulance to a Medford hospital. He was trea...

June

This much I know for sure: I was born in Peralta Hospital in Oakland, California, on November 30, 1948. My parents were Rodney Lloyd Dully and June Louise Pierce Dully. I was their first child, and they named me Howard August Dully, after my father’s father. Rodney was twenty-three. June was thirty-four.

They had been married less than a year. Their wedding was held on Sunday, December 28, 1947, three days after Christmas, at one o’clock in the afternoon, at the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Sacramento, California. The wedding photographs show an eager, nervous couple. He’s in white tie and tails, with a white carnation in his lapel. She’s in white satin, and a veil decorated with white flowers. They are both dark-haired and dark-eyed. Together they are cutting the cake—staring at the cake, not at each other—and smiling.

A reception followed at 917 Forty-fifth Street, at the home of my mother’s uncle Ross and aunt Ruth Pierce. My father’s mother attended. So did his two brothers. One of them, his younger brother, Kenneth, wore a tuxedo all the way up from San Jose on the train.

My father’s relatives were railroad workers and lumberjack types from the area around Chehalis and Centralia, Washington. My dad spent his summers in a lumber camp with one of his uncles. They were logging people.

My father’s father was an immigrant, born in 1899 in a place called Revel, Estonia, in what would later be the Soviet Union. When he left Estonia, his name was August Tulle. When he got to America, where he joined his brothers, Alexander and John— he had two sisters, Marja and Lovisa, whom he left behind in Estonia—he was called August Dully. He later added the first name Howard, because it sounded American to him.

My father’s mother was the child of immigrants from Ireland. She was born Beulah Belle Cowan in Litchfield, Michigan, in 1902. Her family later moved to Portland, Oregon, in time for Beulah to attend high school, where she was so smart she skipped two grades.

August went to Portland, too, because that’s where his brothers were. According to his World War I draft registration card, he was brown-haired, blue-eyed, and of medium height. He got work as a window dresser for the Columbia River Ship Company. He became a mason. He met the redheaded Beulah at a dance. She told her mother that night, “I just met the man I’m going to marry.” She was sixteen. A short while later, they tied the knot and took a freighter to San Francisco for their honeymoon, and stayed. A 1920 U.S. Census survey shows them living in an apartment building on Fourth Street. Howard A. Dully was now a naturalized citizen, working as a laborer in the shipyards.

Sometime after, they moved to Washington, where my grandfather went to work on the railroads. They started having sons—Eugene, Rodney, and Kenneth—before August got sick with tuberculosis. Beulah believed he caught it on that freighter going to San Francisco. He died at home, in bed, on New Year’s Day, 1929. My dad was three years old. His baby brother was only fourteen months old.

Beulah Belle never remarried. She was hardheaded and strong-willed. She said, “I will never again have a man tell me what to do.”

But she had a hard time taking care of her family. She couldn’t keep up payments on the house. When she lost it, the boys went to stay with relatives. My dad was sent to live with an aunt and uncle at age six, and was shuffled from place to place after that. By his own account, he lived in six different cities before he finished high school—born in Centralia, Washington; then shipped around Oregon to Marshfield, Grants Pass, Medford, and Eugene; then to Ryderwood, Washington, where he and his brother Kenneth lived in a logging camp with their former housekeeper Evelyn Townsend and her husband, Orville Black.

At eighteen, Rod left Washington to serve with the U.S. Army, enlisting in San Francisco on December 9, 1943. Though he later was reluctant to talk about it, I know from my uncles that he was sent overseas and stationed in France. He served with the 723rd Railroad Division, laying track in an area near L’Aigle, France, that was surrounded by mines. One of my uncles told me that my father never recovered from the war. He said, “The man who went away to France never came back. He was damaged by what he saw there.”

But another of my uncles told me Rod bragged about having a German girlfriend, so I guess it wasn’t all bad. Not as bad as his brother Gene, who joined the army and got sent to Australia and New Guinea, where he developed malaria and tuberculosis and almost died. He weighed one hundred pounds when he came back to America, and lived at a military hospital in Livermore, California, for a long time after that.

By the time Rod finished his military service, his mother had left her job with Western Union Telegraph, in the Northwest, and moved to Oakland to work for the Southern Pacific Railroad. She was later made a night supervisor, working in the San Francisco office on Market Street. She would still be working there when I was born.

My mother’s folks came from the other end of the economic spectrum. June was the daughter of Daisy Seulberger and Hubert O. Pierce—German on her mother’s side, English on her father’s. Daisy grew up weatlthy, married Pierce, and had three children: Gordon, June, and Hugh. When Pierce died, Daisy married Delos Patrician, another wealthy Bay Area businessman. She moved her family to Oakland, into a huge, three-story shingled home on Newton Avenue. June spent her childhood there.

After his military service, my father relocated to the Bay Area and started taking classes at San Francisco Junior College, learning to be a teacher and doing his undergraduate work in elementary education.

Over the summers, he got part-time work at a popular high Sierras vacation spot, Tuolumne Meadows, in Yosemite. He met a young woman there, working as a housekeeper, who captured his eye. Her name was June.

She was tall, dark, and athletic, and for Rod she was a real catch. She was a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, where she had been active with the Alpha Xi Delta sorority, and had a certificate to teach nursery school. She was from a well-known Oakland family, and for several years she had been a fixture on the local social scene. During the war she had worked in Washington, D.C., as a private secretary to the U.S. congressman from her district. When she returned to Oakland, she often had her name in the newspapers, hosting luncheons and teas for her society friends.

She had been courted by quite a few young men, but her controlling mother, Daisy, drove all the boyfriends away. When she met Rod, June was still beautiful, but she was no longer what you’d call young, especially not at that time. She was thirty-two. Being unmarried at that age during the 1940s was almost like being a spinster.

Their courtship was sudden and passionate. They fell in love over the summer of 1946, and saw each other in San Francisco and Berkeley through the next year. When June returned to work in Yosemite in the summer of ’47, this time at Glen Aulin Camp, Rod left for the lumberyards of northern California and southern Oregon, where he was determined to make enough money to marry June in style. His letters over that summer were eager and filled with love. He was full of plans and promises—for his career, their wedding, the house he would buy her, the family they would have. He was worried that he was not the man June’s mother wanted, or from the right level of society, but he was determined to prove himself. “I expect to make you happy. I won’t marry you and take you into a life you won’t be happy in,” he wrote. “I’m happy now, much happier than I’ve ever been before in my life, cause you’re my little dream girl and my dream is coming true.”

After a hard summer of logging work, the plans for the wedding were made. The ceremony was held three days after Christmas in Sacramento. According to a newspaper story a week later, the couple was “honeymooning in Carmel” after a ceremony in which “the bride wore a white satin gown with a sweetheart neckline, long sleeves ending in points at the wrists and full skirt with a double peplum pointed at the front. Her full-length veil of silk net was attached to a bandeau of seed pearls and orange blossoms. She also carried a handkerchief which has been in her family for 75 years.”

The bride was given away by her uncle Ross, in whose Sacramento house she had been living. The groom’s best man was his brother Kenneth.

According to family stories, some of June’s family objected. Rod was too young for June, Daisy said, and didn’t have good prospects. June may have been uncomfortable with the relative poverty she was marrying into, too. My dad later told people that he got into a fender bender not long after he met June, and that his feelings were hurt when she said she was embarrassed to be seen driving around in his banged-up car.

With a wife to support, my father left school. He and my mother moved up north, to Medford, Oregon, where Rod returned to the lumber business and went to work as a lumber tallyman with the Southern Oregon Sugar Pine Corporation in Central Point, two miles outside of Medford.

Soon the young married couple had a baby on the way—me. Near the end of her term, my mother left my dad in Medford and moved in with her mother in Oakland, a pattern she would repeat for the births of all her children.

If everything had gone as planned, she probably would have returned to Medford and raised a family.

But my father had some bad luck. One morning on a work break he became incoherent and had to be taken by ambulance to a Medford hospital. He was trea...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTantor Audio

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 1400105366

- ISBN 13 9781400105366

- BindingAudio CD

- Number of pages9

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 66.85

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Published by

Tantor Audio

(2007)

ISBN 10: 1400105366

ISBN 13: 9781400105366

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1400105366

Buy New

US$ 66.85

Convert currency

My Lobotomy: A Memoir

Published by

Tantor Audio

(2007)

ISBN 10: 1400105366

ISBN 13: 9781400105366

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1400105366

Buy New

US$ 68.29

Convert currency