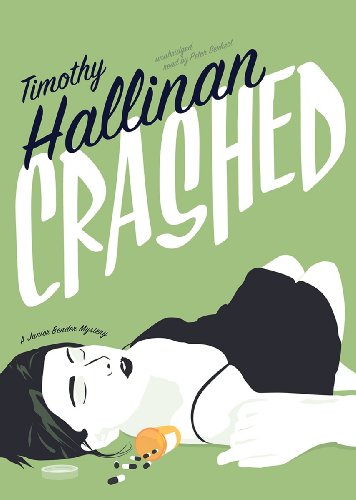

Items related to Crashed (Junior Bender Mysteries)

[MP3CD audiobook format in vinyl case.]

[Read by Peter Berkrot]

Introducing Junior Bender, the favorite burglar turned private investigator of Hollywood crooks

Junior Bender is a Los Angeles burglar with a magic touch. Since he first started breaking into houses at age fourteen, he's never once been caught. But now, after twenty-two years building an exemplary career, Junior has been blackmailed by Trey Annunziato, one of the most powerful crime bosses in LA, into acting as a private investigator on the set of Trey's porn venture, which someone keeps sabotaging. The star Trey has lined up to do all that's unwholesome on camera is Thistle Downing, America's beloved child star, who now lives alone in a drug-induced stupor, destitute and uninsurable. Her starring role will be the scandalous fall-from-grace gossip of rubberneckers across the country. No wonder Trey needs help keeping the production on track.

Junior knows what he should do -- but doing the right thing will land him on the wrong side of LA's scariest mob boss. With the help of his precocious twelve-year-old daughter, Rina, and his criminal sidekick, ex-getaway driver Louie the Lost, Junior will have to pull off a miracle to get out of this mess.

[Read by Peter Berkrot]

Introducing Junior Bender, the favorite burglar turned private investigator of Hollywood crooks

Junior Bender is a Los Angeles burglar with a magic touch. Since he first started breaking into houses at age fourteen, he's never once been caught. But now, after twenty-two years building an exemplary career, Junior has been blackmailed by Trey Annunziato, one of the most powerful crime bosses in LA, into acting as a private investigator on the set of Trey's porn venture, which someone keeps sabotaging. The star Trey has lined up to do all that's unwholesome on camera is Thistle Downing, America's beloved child star, who now lives alone in a drug-induced stupor, destitute and uninsurable. Her starring role will be the scandalous fall-from-grace gossip of rubberneckers across the country. No wonder Trey needs help keeping the production on track.

Junior knows what he should do -- but doing the right thing will land him on the wrong side of LA's scariest mob boss. With the help of his precocious twelve-year-old daughter, Rina, and his criminal sidekick, ex-getaway driver Louie the Lost, Junior will have to pull off a miracle to get out of this mess.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

TIMOTHY HALLINAN is the Edgar- and Macavity Award-nominated author of over a dozen widely praised books, including the 'Poke Rafferty' Bangkok thrillers and the 'Junior Bender' series. In 2010 Hallinan conceived and edited an e-book of original short stories by twenty mystery writers, Shaken: Stories for Japan, with 100 percent of the proceeds going to Japanese disaster relief.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

If I’d liked expressionism, I might have been okay.

But the expressionists don’t do anything for me, don’t even

make my palms itch. And Klee especially doesn’t do anything

for me. My education, spotty as it was, pretty much set my Art

Clock to the fifteenth century in the Low Countries. If it had

been Memling or Van der Weyden, one of the mystical Flemish

masters shedding God’s Dutch light on some lily-filled annunciation,

I would have been looking at the picture when I took it off

the wall. As it was, I was looking at the wall.

So I saw it, something I hadn’t been told would be there.

Just a hairline crack in the drywall, perfectly circular, maybe

the size of a dinner plate. Seen from the side, by someone peeking

behind the painting without moving it, which is what most

thieves would do in this sadly mistrustful age of art alarms, it

would have been invisible. But I’d taken the picture down, and

there it was.

And I’m weak.

I think for everyone in the world, there’s something you

could dangle in front of them, something they would run onto

a freeway at rush hour to get. When I meet somebody, I like to

try to figure out what that is for that person. You for diamonds,

darling, or first editions of Dickens? Jimmy Choo shoes or a

Joseph Cornell box? And you, mister, a thick stack of green? A

troop of Balinese girl scouts? A Maserati with your monogram

on it?

For me, it’s a wall safe. From my somewhat specialized perspective,

a wall safe is the perfect object. To you, it may be a hole

in the wall with a door on it. To me, it’s one hundred percent

potential. There’s absolutely no way to know what’s in there.

You can only be sure of one thing: Whatever it is, it means a hell

of a lot to somebody. Maybe it’s what they’d run into traffic for.

A wall safe is just a question mark. With an answer inside.

Janice hadn’t told me there would be a safe behind the picture.

We’d discussed everything but that. And, of course, that—

meaning the thing I hadn’t anticipated—was what screwed me.

What Janice and I had mostly talked about was the front door.

“Think baronial,” she’d said with a half-smile. Janice had

the half-smile down cold. “The front windows are seven feet

from the ground. You’d need a ladder just to say hi.”

“How far from the front door to the curb?” The bar we were

in was way south of the Boulevard, in Reseda, far enough south

that we were the only people in the place who were speaking

English, and Serena’s Greatest Hits was on permanent loop. The

air was ripe with cilantro and cumin, and the place was mercifully

lacking in ferns and sports memorabilia. A single widescreen

television, ignored by all, broadcast the soccer game. I am

personally convinced that only one soccer game has ever actually

been played, and they show it over and over again from

different camera angles.

As always, Janice had chosen the bar. With Janice in charge

of the compass, it was possible to experience an entire planet’s

worth of bars without ever leaving the San Fernando Valley. The

last one we’d met in had been Lao, with snacks of crisp fish bits

and an extensive lineup of obscure tropical beers.

“Seventy-three feet, nine inches.” She broke off the tip of a

tortilla chip and put it near her mouth. “There’s a black slate

walk that kind of curves up to it.”

I was nursing a Negra Modelo, the king of Hispanic dark

beers, and watching the chip, calculating the odds against her

actually eating it. “Is the door visible from the street?”

“It’s so completely visible,” she’d said, “that if you were a

kid in one of those ’40s musicals and you decided to put on a

show, the front door of the Huston house is where you’d put it

on.”

“Makes the back sound good,” I’d said.

“Aswarm with rottweilers.” She sat back, the jet necklace at

her throat sparkling wickedly and the overhead lights flashing

off the rectangular, black-framed glasses she wore in order to

look like a businesswoman but which actually made her look

like a beautiful girl wearing glasses.

Burglars, of which I am one, don’t like Rottweilers. “But

they’re not in the house, right? Tell me they’re not in the house.”

“They are not. One of them pooped on the Missus’s ninety

thousand-dollar Kirghiz rug.” Janice powdered the bit of chip

between her fingers and let it fall to her napkin. “Or I should

say, one of the Missus’s ninety thousand-dollar Kirghiz rugs.”

“There are several women called Missus?” I asked. “Or several

rugs?”

“Either way,” Janice said, reproachfully straightening her

glasses at me. “The dogs are kept in back, and they get fed like

every other Friday.”

“Meaning no going in through the back,” I said.

“Not unless you want to be kibble,” Janice said. “Or the

side, either. The wall around the yard is flush with the front wall

of the house.”

“Speaking of kibble.”

“Please do,” Janice said. “I so rarely get a chance to.”

“Does anyone drop by to feed the beasts? Am I likely to run

into—”

“No one in his right mind would go into that yard. The only

way to feed them would be to throw a bison over the walls. The

Hustons have a very fancy apparatus, looks like it was built for

the space shuttle. Delivers precise amounts of ravening beastfood

twice a day. So they’re strong and healthy and the old killer

instinct doesn’t dim.”

“So,” I said. “It’s the front door.”

She used the tip of her index finger to slide her glasses down

to the point of her perfect nose, and looked at me over them.

“Afraid so.”

I drained my beer and signaled for another. Janice took a

demure sip of her tonic and lime. I said, “I hate front doors. I’m

going to stand there for fifteen minutes, trying to pick a lock in

plain sight.”

“That’s why we came to you,” she said. “Mr. Ingenuity.”

“You came to me,” I said, “because you know this is the

week I pay my child support.”

Janice was a back-and-forth, working for three or four brokers,

guys with clients who knew where things were and wanted

those things, but weren’t sufficiently hands-on to grab them for

themselves. She’d used me before, and it had worked out okay.

She didn’t know I’d backtracked her to two of her employers.

One of them, an international-grade fence called Stinky Tetweiler,

weighed 300 hard-earned pounds and lived in a long, low

house south of the Boulevard with an ever-changing number

of very young Filipino men with very small waists. Like a lot

of the bigger houses south of Ventura, Stinky’s place had once

belonged to a movie star, back when the Valley was movie-star

territory. In the case of Stinky’s house, the star was Alan Ladd,

although Stinky had rebuilt the house into a sort of collision

between tetrahedrons that would have had old Alan’s ghost, had

he dropped by, looking for the front door.

Janice’s other client, known to the trade only as Wattles,

worked out of an actual office, with a desk and everything,

in a smoked-glass high-rise on Ventura near the 405 Freeway.

His company was listed on the building directory as Wattles

Inc. Wattles himself was a guy who had looked for years like

he would die in minutes. He was extremely short, with a belly

that suggested an open umbrella, a drinker’s face the color of

rare roast beef, and a game leg that he dragged around like an

anchor. I’d hooked onto his back bumper one night and followed

him up into Benedict Canyon until he slowed the car to

allow a massive pair of wrought-iron gates to swing open, then

took a steep driveway up into the pepper trees.

But Janice wasn’t aware I knew any of this. And if she had

been, she wouldn’t have been amused at all.

“Where’s the streetlight?”

She gave me her bad-news smile, brave and full of fraudulent

compassion. “Right in front. More or less directly over the end

of the sidewalk.”

“Illuminating the front door.”

“Brilliantly,” she said. “Don’t think about the front door.

Think about what’s on the other side.”

“I am,” I said. “I’m thinking I have to carry it seventy-three

feet and nine inches to the van. Under a streetlight.”

“You always focus on the negative,” she said. “You need to

do something about that. You want your positive energy to flow

straight and true, and every time you go to the negative, you put

up a little barrier. If it weren’t for your constant focus on negative

energy, your marriage might have gone better.”

God, the things women think they have the right to say. “My

marriage went fine,” I said. “It was before the marriage went

that was difficult.”

“You have to be positive about that, too,” she said. “Without

the marriage, you wouldn’t have Rina.”

Ahh, Rina, twelve years old and the light of my life. “To the

extent I have her, anyway.”

She gave me the slow nod women use to indicate that they

understand our pain, they admire the courage with which we

handle it, and they’re absolutely certain that it’s all our fault. “I

know it’s tough, Kathy being so punitive with visitation. But she’s

your daughter. You’ve got to be happy about that.” Janice put

down her glass and patted me comfortingly on the wrist with wet,

cold fingers. I resisted the impulse to pull my wrist away. After all,

her hand would dry eventually. She was working her way toward

flirting, as she did every time we met, even though we both knew

it wouldn’t lead anywhere. I was still attached to Kathy, my former

wife, and Janice demonstrated no awkwardness or any other

kind of perceptible difficulty turning down dates.

“Of course, I’m happy about that,” I said. And then, because

it was expected, I made the usual move. “Want to go to dinner?”

She lowered her head slightly and regarded me from beneath

her spiky bangs. “Tell me the truth. When you thought about

asking me that question, you anticipated a negative response,

didn’t you?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “It’s the ninth time, and you’ve never

said yes.”

“See what I mean?” she said. “Your negativity has put kinks

in your energy flow.”

“Can you straighten it for me?”

“If your invitation had been made in a purely affirmative

spirit, I might have said yes.”

“Might?” I took a pull off the beer. “You mean I could purify

my spirit, straighten out my energy flow, sterilize my anticipations,

and you still might say no?”

“Oh, Junior,” she said. “There are so many intangibles.”

“Name one.”

The slow head-shake again. “You’re a crook.”

“So are you.”

“I beg to differ,” she said. “I’m a facilitator. I bring together

different kinds of energies to effect the transfer of physical

objects. It’s almost metaphysical.” She held her hands above the

table so her palms were about four inches apart, as though she

expected electricity to flow between them. She turned them so

the left hand was on top. “On one side,” she said, “the energy of

desire: dark, intense, magnetic.” She reversed her hands so the

right was on top. “On the other side, the energy of action: direct,

kinetic, daring.”

“Whooo,” I said. “That’s me?”

“Certainly.”

“Sounds like somebody I’d go out with.”

“And don’t think I don’t want to,” she said, and she narrowed

her eyes mystically, which made her look nearsighted. I’ve always

loved nearsighted women. They’re so easy to help. “Some day the

elements will be in alignment.” She pushed the glass away and got

up, and guys all over the place turned to look. In this bar, Janice

was as exotic as an orchid blooming in the snow.

“A brightly lighted front door,” I said, mostly to slow her

down. I liked watching her leave almost as much as I liked

watching her arrive. “Seventy-three feet to the curb. Carrying

that damn thing.”

“And nine inches.”

“Seventy-three feet, nine inches. In both directions.”

“And you have to solve it by Monday,” she said. “But don’t

worry. You’ll think of something. You always do. When the

child support’s due.”

She gave me a little four-finger wiggle of farewell, turned,

and headed for the door. Every eye in the place was on her backside.

That may be dated, but it was true.

And, of course, I had thought of something. In the abstract the

plan had seemed plausible. Sort of. And it had continued to

seem plausible right up to the moment I pulled up in front of the

house in broad daylight. Then, as I climbed out, wincing into

the merciless July sun that dehydrates the San Fernando Valley

annually, it seemed very much less plausible. I felt a rush of what

Janice would undoubtedly call negative energy, and suddenly it

seemed completely idiotic.

But this was not the time to improvise. It was Monday afternoon

in an upscale neighborhood, and I needed to justify my

presence. Sweating in my dark coveralls, I went around to the

back of the van and opened the rear door. Out of it I pulled a

heavy dolly, which I set down about two feet behind the rear

bumper. I squared my shoulders, the picture of someone about

to do something difficult, leaned in, and very slowly dragged

out an enormous cardboard refrigerator carton, on one side of

which I had stenciled the words SUB ZERO. This was no neighborhood

for Kelvinators or Maytags.

Back behind the house, the dogs began to bark. They were all

bassos, ready to sing the lead in “Boris Godunov,” and I thought

I could distinguish four of them, sounding like they weighed a

combined total of 750 pounds, mostly teeth. Christ, I was seventy-

three feet, nine inches from the door, not even standing on

the damn lawn yet, and I was already too close for them.

Kathy, my ex-wife, has taught Rina to love dogs. It doesn’t

matter how obscure the opportunity for revenge is; Kathy will

grab it like a trapeze.

Grunting and straining, I tilted the box down and slid it onto

the dolly. I’d put a couple of sandbags in the bottom of the box,

mostly to keep it from tipping or being blown over, but it took

some work to make it look heavy enough. Once I had it on the

dolly, I tilted it back and made a big production of hauling it up

the four-inch vertical of the curb. Then I walked away from it

so I was visible from all directions, pulled out a cell phone, and

called myself.

I listened to my message for a second and then talked into

the phone. With it pressed to my ear, I turned to face the house,

looked up at a second-story window, and gave a little wave. The

cell phone slipped easily into the top pocket of the coveralls, and

I grabbed the dolly handles, put my back into tilting it up onto

the wheels, and towed the carton up the slate path.

At the door, I positioned the box so the side with SUB ZERO

on it faced the street. Then I got in between the box and the door

and pushed open the flap I’d cut in the closest side of the box—

just three straight lines with a box cutter, leaving the fourth side

of the rectangle intact to serve as a hinge. The flap was about five

feet high and three feet wide, and it swung open into the box. I

climbed in. From the street, all anyone would see was the box.

The door was fancy, not functional. Heavy dark wood, brass

hardware, and a big panel of stained glass in the upper half—

some sort of coat of arms, a characteristically confused collision

of symbolic elements that included an ax, a rose, and something

that looked suspiciously like a pair of pliers. A good graphic artist

could have made a fortune in the Middle Ages.

My working valise was at the bottom of the box. I snapped

on a pair of surgical gloves, pulled out ...

But the expressionists don’t do anything for me, don’t even

make my palms itch. And Klee especially doesn’t do anything

for me. My education, spotty as it was, pretty much set my Art

Clock to the fifteenth century in the Low Countries. If it had

been Memling or Van der Weyden, one of the mystical Flemish

masters shedding God’s Dutch light on some lily-filled annunciation,

I would have been looking at the picture when I took it off

the wall. As it was, I was looking at the wall.

So I saw it, something I hadn’t been told would be there.

Just a hairline crack in the drywall, perfectly circular, maybe

the size of a dinner plate. Seen from the side, by someone peeking

behind the painting without moving it, which is what most

thieves would do in this sadly mistrustful age of art alarms, it

would have been invisible. But I’d taken the picture down, and

there it was.

And I’m weak.

I think for everyone in the world, there’s something you

could dangle in front of them, something they would run onto

a freeway at rush hour to get. When I meet somebody, I like to

try to figure out what that is for that person. You for diamonds,

darling, or first editions of Dickens? Jimmy Choo shoes or a

Joseph Cornell box? And you, mister, a thick stack of green? A

troop of Balinese girl scouts? A Maserati with your monogram

on it?

For me, it’s a wall safe. From my somewhat specialized perspective,

a wall safe is the perfect object. To you, it may be a hole

in the wall with a door on it. To me, it’s one hundred percent

potential. There’s absolutely no way to know what’s in there.

You can only be sure of one thing: Whatever it is, it means a hell

of a lot to somebody. Maybe it’s what they’d run into traffic for.

A wall safe is just a question mark. With an answer inside.

Janice hadn’t told me there would be a safe behind the picture.

We’d discussed everything but that. And, of course, that—

meaning the thing I hadn’t anticipated—was what screwed me.

What Janice and I had mostly talked about was the front door.

“Think baronial,” she’d said with a half-smile. Janice had

the half-smile down cold. “The front windows are seven feet

from the ground. You’d need a ladder just to say hi.”

“How far from the front door to the curb?” The bar we were

in was way south of the Boulevard, in Reseda, far enough south

that we were the only people in the place who were speaking

English, and Serena’s Greatest Hits was on permanent loop. The

air was ripe with cilantro and cumin, and the place was mercifully

lacking in ferns and sports memorabilia. A single widescreen

television, ignored by all, broadcast the soccer game. I am

personally convinced that only one soccer game has ever actually

been played, and they show it over and over again from

different camera angles.

As always, Janice had chosen the bar. With Janice in charge

of the compass, it was possible to experience an entire planet’s

worth of bars without ever leaving the San Fernando Valley. The

last one we’d met in had been Lao, with snacks of crisp fish bits

and an extensive lineup of obscure tropical beers.

“Seventy-three feet, nine inches.” She broke off the tip of a

tortilla chip and put it near her mouth. “There’s a black slate

walk that kind of curves up to it.”

I was nursing a Negra Modelo, the king of Hispanic dark

beers, and watching the chip, calculating the odds against her

actually eating it. “Is the door visible from the street?”

“It’s so completely visible,” she’d said, “that if you were a

kid in one of those ’40s musicals and you decided to put on a

show, the front door of the Huston house is where you’d put it

on.”

“Makes the back sound good,” I’d said.

“Aswarm with rottweilers.” She sat back, the jet necklace at

her throat sparkling wickedly and the overhead lights flashing

off the rectangular, black-framed glasses she wore in order to

look like a businesswoman but which actually made her look

like a beautiful girl wearing glasses.

Burglars, of which I am one, don’t like Rottweilers. “But

they’re not in the house, right? Tell me they’re not in the house.”

“They are not. One of them pooped on the Missus’s ninety

thousand-dollar Kirghiz rug.” Janice powdered the bit of chip

between her fingers and let it fall to her napkin. “Or I should

say, one of the Missus’s ninety thousand-dollar Kirghiz rugs.”

“There are several women called Missus?” I asked. “Or several

rugs?”

“Either way,” Janice said, reproachfully straightening her

glasses at me. “The dogs are kept in back, and they get fed like

every other Friday.”

“Meaning no going in through the back,” I said.

“Not unless you want to be kibble,” Janice said. “Or the

side, either. The wall around the yard is flush with the front wall

of the house.”

“Speaking of kibble.”

“Please do,” Janice said. “I so rarely get a chance to.”

“Does anyone drop by to feed the beasts? Am I likely to run

into—”

“No one in his right mind would go into that yard. The only

way to feed them would be to throw a bison over the walls. The

Hustons have a very fancy apparatus, looks like it was built for

the space shuttle. Delivers precise amounts of ravening beastfood

twice a day. So they’re strong and healthy and the old killer

instinct doesn’t dim.”

“So,” I said. “It’s the front door.”

She used the tip of her index finger to slide her glasses down

to the point of her perfect nose, and looked at me over them.

“Afraid so.”

I drained my beer and signaled for another. Janice took a

demure sip of her tonic and lime. I said, “I hate front doors. I’m

going to stand there for fifteen minutes, trying to pick a lock in

plain sight.”

“That’s why we came to you,” she said. “Mr. Ingenuity.”

“You came to me,” I said, “because you know this is the

week I pay my child support.”

Janice was a back-and-forth, working for three or four brokers,

guys with clients who knew where things were and wanted

those things, but weren’t sufficiently hands-on to grab them for

themselves. She’d used me before, and it had worked out okay.

She didn’t know I’d backtracked her to two of her employers.

One of them, an international-grade fence called Stinky Tetweiler,

weighed 300 hard-earned pounds and lived in a long, low

house south of the Boulevard with an ever-changing number

of very young Filipino men with very small waists. Like a lot

of the bigger houses south of Ventura, Stinky’s place had once

belonged to a movie star, back when the Valley was movie-star

territory. In the case of Stinky’s house, the star was Alan Ladd,

although Stinky had rebuilt the house into a sort of collision

between tetrahedrons that would have had old Alan’s ghost, had

he dropped by, looking for the front door.

Janice’s other client, known to the trade only as Wattles,

worked out of an actual office, with a desk and everything,

in a smoked-glass high-rise on Ventura near the 405 Freeway.

His company was listed on the building directory as Wattles

Inc. Wattles himself was a guy who had looked for years like

he would die in minutes. He was extremely short, with a belly

that suggested an open umbrella, a drinker’s face the color of

rare roast beef, and a game leg that he dragged around like an

anchor. I’d hooked onto his back bumper one night and followed

him up into Benedict Canyon until he slowed the car to

allow a massive pair of wrought-iron gates to swing open, then

took a steep driveway up into the pepper trees.

But Janice wasn’t aware I knew any of this. And if she had

been, she wouldn’t have been amused at all.

“Where’s the streetlight?”

She gave me her bad-news smile, brave and full of fraudulent

compassion. “Right in front. More or less directly over the end

of the sidewalk.”

“Illuminating the front door.”

“Brilliantly,” she said. “Don’t think about the front door.

Think about what’s on the other side.”

“I am,” I said. “I’m thinking I have to carry it seventy-three

feet and nine inches to the van. Under a streetlight.”

“You always focus on the negative,” she said. “You need to

do something about that. You want your positive energy to flow

straight and true, and every time you go to the negative, you put

up a little barrier. If it weren’t for your constant focus on negative

energy, your marriage might have gone better.”

God, the things women think they have the right to say. “My

marriage went fine,” I said. “It was before the marriage went

that was difficult.”

“You have to be positive about that, too,” she said. “Without

the marriage, you wouldn’t have Rina.”

Ahh, Rina, twelve years old and the light of my life. “To the

extent I have her, anyway.”

She gave me the slow nod women use to indicate that they

understand our pain, they admire the courage with which we

handle it, and they’re absolutely certain that it’s all our fault. “I

know it’s tough, Kathy being so punitive with visitation. But she’s

your daughter. You’ve got to be happy about that.” Janice put

down her glass and patted me comfortingly on the wrist with wet,

cold fingers. I resisted the impulse to pull my wrist away. After all,

her hand would dry eventually. She was working her way toward

flirting, as she did every time we met, even though we both knew

it wouldn’t lead anywhere. I was still attached to Kathy, my former

wife, and Janice demonstrated no awkwardness or any other

kind of perceptible difficulty turning down dates.

“Of course, I’m happy about that,” I said. And then, because

it was expected, I made the usual move. “Want to go to dinner?”

She lowered her head slightly and regarded me from beneath

her spiky bangs. “Tell me the truth. When you thought about

asking me that question, you anticipated a negative response,

didn’t you?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “It’s the ninth time, and you’ve never

said yes.”

“See what I mean?” she said. “Your negativity has put kinks

in your energy flow.”

“Can you straighten it for me?”

“If your invitation had been made in a purely affirmative

spirit, I might have said yes.”

“Might?” I took a pull off the beer. “You mean I could purify

my spirit, straighten out my energy flow, sterilize my anticipations,

and you still might say no?”

“Oh, Junior,” she said. “There are so many intangibles.”

“Name one.”

The slow head-shake again. “You’re a crook.”

“So are you.”

“I beg to differ,” she said. “I’m a facilitator. I bring together

different kinds of energies to effect the transfer of physical

objects. It’s almost metaphysical.” She held her hands above the

table so her palms were about four inches apart, as though she

expected electricity to flow between them. She turned them so

the left hand was on top. “On one side,” she said, “the energy of

desire: dark, intense, magnetic.” She reversed her hands so the

right was on top. “On the other side, the energy of action: direct,

kinetic, daring.”

“Whooo,” I said. “That’s me?”

“Certainly.”

“Sounds like somebody I’d go out with.”

“And don’t think I don’t want to,” she said, and she narrowed

her eyes mystically, which made her look nearsighted. I’ve always

loved nearsighted women. They’re so easy to help. “Some day the

elements will be in alignment.” She pushed the glass away and got

up, and guys all over the place turned to look. In this bar, Janice

was as exotic as an orchid blooming in the snow.

“A brightly lighted front door,” I said, mostly to slow her

down. I liked watching her leave almost as much as I liked

watching her arrive. “Seventy-three feet to the curb. Carrying

that damn thing.”

“And nine inches.”

“Seventy-three feet, nine inches. In both directions.”

“And you have to solve it by Monday,” she said. “But don’t

worry. You’ll think of something. You always do. When the

child support’s due.”

She gave me a little four-finger wiggle of farewell, turned,

and headed for the door. Every eye in the place was on her backside.

That may be dated, but it was true.

And, of course, I had thought of something. In the abstract the

plan had seemed plausible. Sort of. And it had continued to

seem plausible right up to the moment I pulled up in front of the

house in broad daylight. Then, as I climbed out, wincing into

the merciless July sun that dehydrates the San Fernando Valley

annually, it seemed very much less plausible. I felt a rush of what

Janice would undoubtedly call negative energy, and suddenly it

seemed completely idiotic.

But this was not the time to improvise. It was Monday afternoon

in an upscale neighborhood, and I needed to justify my

presence. Sweating in my dark coveralls, I went around to the

back of the van and opened the rear door. Out of it I pulled a

heavy dolly, which I set down about two feet behind the rear

bumper. I squared my shoulders, the picture of someone about

to do something difficult, leaned in, and very slowly dragged

out an enormous cardboard refrigerator carton, on one side of

which I had stenciled the words SUB ZERO. This was no neighborhood

for Kelvinators or Maytags.

Back behind the house, the dogs began to bark. They were all

bassos, ready to sing the lead in “Boris Godunov,” and I thought

I could distinguish four of them, sounding like they weighed a

combined total of 750 pounds, mostly teeth. Christ, I was seventy-

three feet, nine inches from the door, not even standing on

the damn lawn yet, and I was already too close for them.

Kathy, my ex-wife, has taught Rina to love dogs. It doesn’t

matter how obscure the opportunity for revenge is; Kathy will

grab it like a trapeze.

Grunting and straining, I tilted the box down and slid it onto

the dolly. I’d put a couple of sandbags in the bottom of the box,

mostly to keep it from tipping or being blown over, but it took

some work to make it look heavy enough. Once I had it on the

dolly, I tilted it back and made a big production of hauling it up

the four-inch vertical of the curb. Then I walked away from it

so I was visible from all directions, pulled out a cell phone, and

called myself.

I listened to my message for a second and then talked into

the phone. With it pressed to my ear, I turned to face the house,

looked up at a second-story window, and gave a little wave. The

cell phone slipped easily into the top pocket of the coveralls, and

I grabbed the dolly handles, put my back into tilting it up onto

the wheels, and towed the carton up the slate path.

At the door, I positioned the box so the side with SUB ZERO

on it faced the street. Then I got in between the box and the door

and pushed open the flap I’d cut in the closest side of the box—

just three straight lines with a box cutter, leaving the fourth side

of the rectangle intact to serve as a hinge. The flap was about five

feet high and three feet wide, and it swung open into the box. I

climbed in. From the street, all anyone would see was the box.

The door was fancy, not functional. Heavy dark wood, brass

hardware, and a big panel of stained glass in the upper half—

some sort of coat of arms, a characteristically confused collision

of symbolic elements that included an ax, a rose, and something

that looked suspiciously like a pair of pliers. A good graphic artist

could have made a fortune in the Middle Ages.

My working valise was at the bottom of the box. I snapped

on a pair of surgical gloves, pulled out ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBlackstone Audiobooks

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 1470838117

- ISBN 13 9781470838119

- BindingMP3 CD

- Rating

US$ 37.83

Shipping:

US$ 47.89

From Germany to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Crashed (Junior Bender Mysteries, Band 1)

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: Sehr gut. Unabridged. 0 Gepflegter, sauberer Zustand. 23058061/2 Altersfreigabe FSK ab 0 Jahre MP3 CD, Größe: 13.5 x 1.5 x 19.1 cm. Seller Inventory # 230580612

Buy Used

US$ 37.83

Convert currency