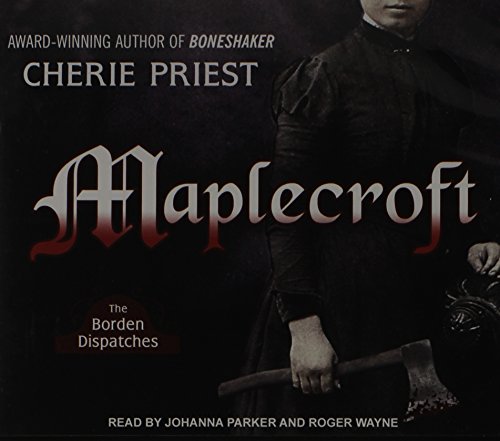

Items related to Maplecroft: The Borden Dispatches (Borden Dispatches,...

But it is not far enough from the affliction that possessed my parents. Their characters, their very souls, were consumed from within by something that left malevolent entities in their place. It originates from the ocean's depths, plaguing the populace with tides of nightmares and madness. This evil cannot hide from me. No matter what guise it assumes, I will be waiting for it. With an axe.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Praise for Maplecroft

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THESE ARE THE THINGS AN EARTHQUAKE BRINGS

Lizzie Andrew Borden

MARCH 17, 1894

No one else is allowed in the cellar.

Emma has a second key, in case I am injured or trapped down there; but Emma also has instructions about how and when to use that key. When she knocks upon the cellar door, I must always reply, “Emma dear, I’m nearly finished.” Even if I’m not working on anything at all. Even if I’m simply down there, writing in my journals. If I say anything else when she knocks, or if I do not respond—my elder sister knows what to do: She must summon Doctor Seabury, and then prevent him from descending into the cellar unarmed.

I wish there were someone closer she could send for, but no one else would come.

The good doctor, though . . . he could be persuaded to attend us, I believe. And he’s a large man, sturdy, and in good health for a fellow of his age. Quite a commanding presence, very much the old soldier, which is no surprise. During the War Between the States, he served as a field surgeon—I know that much. He must’ve been quite young, but the military training has served him well through the years, even in such a provincial setting as Fall River.

Yes, I think all things being equal, he’s the last and best chance either Emma or I would have, were either of us to meet with some accident. And between the two of us, I suppose it must be admitted—to myself, if no one else—that accidents are more likely to befall me than her.

Ah, well. I’d take up safer hobbies if I could.

I locked the cellar door behind myself, and proceeded down the narrow wood-slat stairs into the darkness of that half-finished pit, once intended for vegetables, roots, or wines. I’ve paid a pretty penny to refurbish the place so that the floor is stable and the walls are stacked with stone. During wet weather, those stones weep buckets and the floor creaks something awful, but by and large it’s secure enough.

Secure and quiet. Dreadfully so, as I’ve learned on occasion. I could scream my head off down there and Emma could be reading peacefully by the fireplace. She’d never hear a thing.

Obviously this concerns me, but what can I do? My precautions are for the safety and well-being of us both.

Of us all.

I lit the gas fixtures as I went. All three came on with a turn of their switches, and by the time I reached the final stair I cast a huge, long shadow—as if I were a giant in my own laboratory.

My laboratory. That feels like the wrong word, but what else can I call it? This is the place where I’ve gathered my specimens, collected my tools, recorded my findings, and meticulously documented all experiments and tests. So the word must apply.

I cannot claim to have made any real progress, except I now know a thousand ways in which I have failed to save anyone, anywhere. From anything.

It would be easier, I think, if I knew there was some finite number of possibilities—an absolute threshold of events I could try in order to produce successful, repeatable results. If I knew there were only a million hypothetical trials, I would cheerfully, painstakingly navigate them all from first to last. Such a task might take the rest of my life, but it’d be a comfort to know I was forcing some definite evolution to a crisis.

But I don’t know any such thing. And more likely, the possibilities measure in the billions—or are altogether endless. I shudder to consider it, but I’d be a fool if I didn’t.

So I go on wishing. I wish for the prospect of a definite finale, and I wish I were not alone.

That would make things easier, too—if there were someone else to share the burden, apart from poor Emma. And though she appeared invulnerably strong when I was a child (due in part to the ten-year difference in age between us), in our middling years her health has failed her in a treacherous fashion. Often she’s confined to a bed or a seat, and she coughs with such frequency that I only notice it anymore if she’s stopped. Consumption, everyone supposes. Consumption, and possibly the shock of what befell our father and Mrs. Borden.

That’s the rest of what everyone supposes, and that’s probably true, in its way. It’s true that Emma has never been herself since those last weeks when she fled the house, insisting that something was wrong and that she felt a hideous suffocation, and she needed to find some other air to breathe.

That’s how she put it. Finding other air to breathe.

At the time we assumed she only wanted a change of scenery from the fighting, the bickering, and the sudden appearance of William—and all the difficulties he inspired.

True, true. All of it true, but incomplete.

We were both contaminated by something, by whatever took the other Bordens. It worked its way inside us, too—whether by breath, or through the skin, or through something we consumed, still I cannot say. All I can do is pray that we caught it in time, and that we have removed ourselves beyond its influence . . .

Alas.

I almost wrote, “before any permanent damage was done.” But then I thought of Emma and her fragile lungs, and her bloodied handkerchiefs. And I thought also of my poisoned dreams and the awful visions that sometimes distract me even while waking. I often believe in retrospect that they’re telling me something crucial . . . but doesn’t every dreamer insist that every dream is meaningful at the time? However, in the retelling, the dreams (and my visions) are trite at best, disturbing at worst.

I will not burden Emma with them, for she is burdened enough with her own body’s complaints. And I don’t have anyone else to tell, not really. Not except for Nance, and I fear to the point of fretful, bowel-clenching sickness that I might chase her away even without the secrets that darken the space between us. Little though I see her lately, since her most recent job for that director, Peter Rasmussen . . . still I value beyond my life the time I spend with her beside me.

Nance has accused me, once or twice in teasing, of being a sentimental old fool. She’s right, absolutely.

She’s also young—very young. So young it’s all the more inappropriate, how we carry on between ourselves. Carelessly, it’s been said. Wantonly, it’s been accused. Nance wouldn’t argue with either one; she would laugh instead, and add her own descriptors with even less propriety. But women her age, barely out of their teens and with the whole world before them, they haven’t yet had time to lose the things they love. Every affair is a fairy tale or a tragedy, and either one is fine so long as the story is good. Every love is all or nothing, and even their “nothings” are poetry. They don’t yet know how the years fade and stretch the highs and the lows, wearing them thin, making them vulnerable. They haven’t yet known much of death.

I don’t think I’m talking about Nance anymore.

It doesn’t matter. She won’t come again for weeks, maybe months. And I won’t hold that against her.

I can’t. I’m the one who asked her to stay away.

· · ·

Upon reaching the cellar’s floor I turned on the two largest gaslights, and the bleak, cluttered space was flooded with a quivering white light that joined the illumination from the stairs. I blinked against it. I set one hand on the nearest table and leaned there while my eyes adjusted, and when they did, I took a very deep breath and considered the week’s samples.

My laboratory is a large open room, undivided except by two rows of three tables each. Several of the tables are occupied by jars of assorted sizes, ranging from tubes as small as my thumb to bigger containers that could easily hold a loaf of bread. Floating within them in an alcohol solution are things I’ve collected over the last two years. Some are recognizable as varieties of ordinary ocean flora and fauna, and some are not. I’ve gathered plants, fish, sea jellies, crustaceans, and cephalopods by the score, and I’ve cataloged them all by their deformities. Some are laden with so many aberrations that it’s impossible to tell what the original species might have been; some have minor exterior problems, though these malformations often mask more obvious internal ones.

For example, one of my larger jars holds a brown octopus (octopus vulgaris) with two distinct heads and three extra tentacles. Upon a cursory dissection of it, I discovered that it also had twice the usual complement of hearts—which is to say six of them. Two of these hearts were pitiably underdeveloped, but distinct and bafflingly present.

I’ve also found fish with too many sets of gills, grotesquely oversized fins, or no eyes whatsoever. I’ve retrieved lobsters with three claws, with one claw, with no tail, or no legs. The story is much the same for simpler creatures, though the abnormalities are sometimes harder to spot.

My conclusions, such as they are, sound like utter madness. But I believe they are borne out by the books that are stacked on the other desks, where I’ve had to establish the library. We couldn’t put shelves along the wall or else the damp would ruin them, so two of the farthest tables are stacked with shorter bookcases. Each of these cases is piled with volumes too arcane and peculiar to display upstairs, despite the fact that we virtually never see visitors.

Upon reflection, I’m not entirely sure who I’m hiding them from. Not Emma. She’s the one who ordered most of them, and regardless, she’s read them already.

Nance? No, I don’t think so. Nance is difficult to scandalize, and she’s aware of my interests—though not aware of their extent, or their origins. If pressed, I’d have to say that I’m hiding the books from Nance’s friends, who sometimes accompany her when she visits.

Or maybe I only do it out of optimism, from the eternal hope that someday we’ll have friends of our own again.

It’s ridiculous, I know. My infamy taints my sister, who declares her intent to stay by my side even as we both know she’s too fragile for any other recourse. And it’s furthermore ridiculous because our respective activities require a certain solitude. I must be left alone to pursue my experiments, and Emma could never continue her correspondences with eminent scientists and biologists if anyone knew that “E. A. Jackson” was a woman. Thank heavens none of her correspondents has ever dropped by for a spot of tea. I honestly don’t know what she’d tell them.

It’s a blessing, really, that no one will have anything to do with us.

· · ·

I picked up the nearest lantern and lit it. It’s a special one, affixed with mirrors and foils, to direct the light wherever I wish to project it—and I wanted to brighten the back right table, beside the two oversized sinks and an assortment of hoses, hooks, tongs, knives, and scalpels. There, in one of my larger jars, a peculiar mass had sunk to the bottom, where it sizzled enough to muster a light froth that foamed throughout the container. It’d been sizzling that way for two days, while an acid solution nibbled away at the calcite. Within that mass, I have always sensed there was something important.

When I first discovered it, the object was approximately the size of a small melon, and it lacked any geometric shape to speak of. If I were to assign it any general description, I’d say that it looked like a very large hand grabbed a fistful of the ocean bottom and squeezed until the sediment became stone. It was roughly column-like, with bits of finny fluting. Primarily it was white, or the swirled browns and bleached hues of ocean detritus.

I found it on one of my evening walks on the beach, after dark with a lantern. And at the risk of sounding hysterical, I believe that I felt it. I believe that it called me, and I heard it.

So I retrieved it, setting my lantern on the sand and hefting the rock into my hands, holding it there. Though it was in no way shaped like a shell, I held it up to my ear and listened—for what, I cannot say.

But this draw, this lure. I’ve felt it before and I don’t yet understand the full implications of what it means, but I know I should’ve taken more care with the sample. I should’ve wrapped it in my apron and carried it that way, without touching it bare-handed, but I didn’t. I cradled it in one naked arm and held my light aloft with the other, all the way back home.

There, I returned to my senses and dumped it into the jar full of acid to let science sort it out.

· · ·

I forcibly tugged my attention away from the bubbling, hypnotic jar and turned instead to a box I keep buried beneath the floor.

With a quick pop of a pry bar at just the right spot, a row of boards slipped out of place. My floor is not as seamless and immutable as it appears; it is riddled with compartments such as this one.

Some people keep cupboards in a wall. I keep them in the ground.

Beneath this lid, which I’d disguised as flooring, a box squatted—smelling of wet soil and worms, and moss, and lichen, and whatever else blackens the earth below my home. I could have pried it out and brought it up to the floor, but I chose not to. For some reason, I felt that the box was safest right there, underneath everything. Underneath my house, my basement, my floor.

I would bury it deeper if I could, but I need to keep it within reach, this little repository of evil. Soon, I might need to add to its contents—depending on what lies at the heart of that strange mass which dissolves by atoms on the back right table.

I’m not sure what made me reach into the hole and touch the iron-bound top of that box.

Yes, again, I’m mired in uncertainties and suspicions, but I have taken all the precautions I can. More than likely, at least half of them don’t work. But when I don’t know what works and what does not work, all I can do is throw it all in together, and trust that some measure of success will result, even if that success is diluted by imprecision.

So there is a box that is lined with lead and sealed with iron bands, and inscribed with unsettling symbols, and buried in the earth, beneath the rowan-wood boards that make up the floor of my basement.

I reached down into the hole and fumbled with the latches until it was unfastened all around, and then I lifted the lid for no good reason whatsoever. I’d like to say that the motion was dreamlike on my behalf, that I scarcely recall doing it; but this isn’t quite true, because I remember watching my arm extend, and my fingers manipulate the fasteners, and then lift the lid. I recall every bit of this, and in my recollection, I was fully in control of myself.

Except that I can’t have been.

Because now, with some distance from that box and that basement, I know full well that it was a dangerous, absurd thing to do—and that not all the gold in the world, nor all the threats or complaints, could ever persuade me to open it right now, with nothing to add to its treasure.

And I jot this down, all of it, in case—upon eventual review—some pattern is revealed. ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTantor Audio

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1494502461

- ISBN 13 9781494502461

- BindingAudio CD

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want