Items related to Glimpses of Paradise: The marvel of massed animals

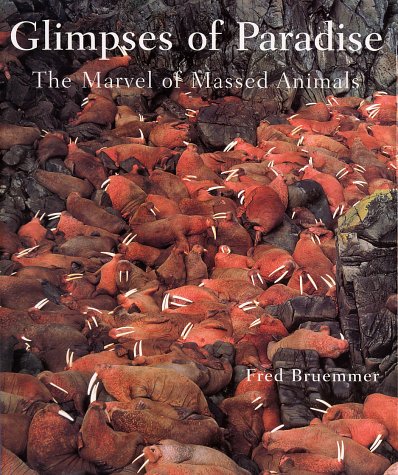

For ten years, internationally respected photographer and writer Fred Bruemmer traveled around the world to capture on film the staggering spectacle of massed animals of all kinds. Glimpses of Paradise is just that: a peek into a world rapidly fading into extinction -- an Eden where animals and birds pulsed across the earth and through the air in huge numbers. Coupled with Bruemmer's engaging and earnest text, this is a stunning record of a world few have the privilege to see.

While forty-five animal and bird species from all corners of the globe are featured, all of these massings reveal the truly remarkable, interdependent relationships that are the web of nature. Masses of shorebirds migrating to their arctic breeding grounds stop along the Jersey shores to fill up on billions of eggs left by massing horseshoe crabs. In the Amazon, pierid butter- flies mass near Madre de Dios River, where they sip the salty tears of nesting turtles. Risking their lives, Peru's blue-headed parrots flock to exposed cliff-sides to lick the clay that protects them from the poisons in their preferred food, unripe fruit.

From across the world, Bruemmer brings us stunning photographs of nature's spectacles, including:

- a million wildebeests -- the last great massing of an animal species in Africa the world's largest black-browed albatross colony nesting on the Falklands Island Africa's immense Rift Valley is dusted pink by a million flamingos the world's only colonies of king penguins on Antarctica's South Georgia Island millions of monarch butterflies filling the tree tops of remote Mexican mountains the roar of Canada's migrating caribou, last of North America's great wildlife herds millions of ladybird beetles "painting" remote Arizona hills in a deep red lacquer a thousand beluga whales congregating in Canada's Arctic to mate, molt and talk

Glimpses of Paradise is a remarkable vision of a natural world teeming with life. It is an essential addition to nature photography collections, both for its accurate and up-to-date text and for its stunning wildlife images.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Fred Bruemmer is an internationally celebrated writer and photographer. His previous titles include World of the Polar Bear, Seasons of the Seal, The Long Hunt and Arctic Animals and the ground-breaking The Arctic World, one of the first trade books to feature nature photography of the Arctic. He lives in Montreal, Canada.

Introduction

In 1919, toward the end of his life, the great American naturalist John Burroughs looked back in sorrow at the vanished world of his youth. Then spring had brought "vast armies of passenger pigeons ... the naked beechwoods would suddenly become blue with them, and vocal with their soft, childlike calls. It was such a spectacle of beauty, of joyous, copious animal life, of fertility in the air and in the wilderness, as to make the heart glad. I have seen the fields and woods fairly inundated for a day or two with these fluttering, piping, blue-and-white hosts. The very air at times seemed suddenly to turn to pigeons."

The passenger pigeon was once the most numerous bird in the world. Alexander Wilson, the so-called father of American ornithology, estimated in 1808 that one Kentucky flock numbered more than two billion birds. John James Audubon saw such a flock cross the Ohio River in 1813: "The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noonday was obscured as by an eclipse."

Death waited for the massed pigeons. "The people were all in arms," wrote Audubon. "The banks of the Ohio were crowded with men and boys incessantly shooting ... Multitudes were thus destroyed."

Market hunters killed the birds in millions. In 1805, Audubon saw "schooners loaded in bulk with pigeons ... coming in to the wharf at New York," and on New York markets passenger pigeons were sold for one cent a piece.

Farmers shot adult pigeons, knocked down nests and chicks, and fattened their hogs with the dying birds. Sport hunters captured passenger pigeons, sewed their eyes shut, and set them out as decoys on small perches to attract other pigeons into shooting range (hence the term "stool pigeon").

By the 1880s the marvelous flights of massed pigeons ended, never to be seen again. Ruthlessly hunted, the birds became rare. The last wild passenger pigeon was shot on March 24, 1900. The very last passenger pigeon on earth, a female named Martha, died at the age of 29 at 4 p.m. on September 1, 1914 in the Cincinnati Zoo. All that remains of these lovely birds that once filled the sky in rushing masses of life are 1,532 skins and mounts in the museums of the world, where their luster has faded.

The mighty bison, the largest land animal in North America, nearly shared the passenger pigeon's fate. In herds that numbered 100,000 or more, these animals roamed the infinite prairies. When they migrated south in fall to better grazing grounds, early European explorers saw streams of the mighty animals fill the land from horizon to horizon, and it filled them with awe. The total number of bison was estimated to be about 60 million. They were probably the most numerous large animals on earth.

"The Bison has several enemies," wrote Audubon, "The worst is, of course, man." Bison formed the basis of existence for the Plains Indians, but since there were few of them and their weapons were simple, they never threatened the vast herds. That changed when white hunters came to the plains. They were dubbed "buffalo butchers," or "hide and tongue hunters," because they took only the skins that could be sold and the bison's tongues, which were prized as a delicacy. They left the carcasses to rot. In 1882 alone, the Northern Pacific Railway carried 200,000 bison hides out of Montana and the Dakotas. The vast herds dwindled, and the Indians starved. "A cold wind blew across the prairies when the last buffalo fell ... a death-wind for my people," mourned the great Indian chief Sitting Bull.

A few animals did survive the slaughter. In 1889, William T. Hornaday of the Smithsonian Institution estimated that 835 bison remained, 200 of them in Yellowstone National Park. Legislation was introduced to protect the last few bison. Their numbers began to increase, but the animals were limited to parks and reserves, for nearly all their vast prairie realm was turned into farms and ranches.

Humans have multiplied prodigiously and most of the ancient animal wealth of our world has been destroyed. We shall never see passenger pigeons again, and the great herds of bison are a wonder of times past. But here and there, for a variety of reasons, some animal species still exist in huge numbers and convey in their multitude a vision of Eden, of a world that once existed.

I have searched for paradise for more than 30 years. I've sought out those magic places where animals congregate in large numbers, places that teem with the fullness of life.

Not surprisingly, some of the greatest concentrations of animals are in regions where humans do not live or where populations are small-the Far North and the Far South, the Arctic and the Antarctic.

In the dialect of northwestern Greeniand's Polar Inuit May is called agpaliarssuit tikarfiat, which means "the dovekies are coming." I was in that part of the world in May of 1971. I stood at the floe edge with Jes Qujaukitsok, an Inuit hunter. We were waiting for seals, and I was also hoping to see narwhal. It was an enchanted night, clear and cold and beautiful; the sea glossy black, the ice deep blue, the light honey yellow on the far mountains. Belugas swam in the distance, their milky white backs arching out of the dark water. We could hear them trill and grunt in the quiet of the night. Eider ducks flew past in great flocks. And then the dovekies came -- great dark clouds in the blue-green sky, hundreds of thousands, all winging north, toward the great breeding slopes of the Siorapaluk-Etah area to keep their date with destiny.

Thirty years later I was on South Georgia, a subantarctic island with lush green valleys hemmed by glittering glaciers. On great Salisbury Plain stood nearly half a million king penguins, the most beautiful of all penguins. Each adult bird was nearly three feet (1m) tall, its belly glossy white, its back a shining slate blue, with glowing golden orange patches on nape and bill and bib. In addition to the elegant adults there were groups of thick-downed, solemn hungry chicks. They stood like tubby men in fuzzy cloaks, waiting for their parents to arrive with food. I looked down from a slope and beneath me the neatly spaced birds spread toward the far hills in a marvelous tapestry of life.

Many years ago, when the migration routes of caribou were still relatively unknown, a biologist and I followed one large herd by plane, flying high above the animals every day. It was late fall and the caribou were marching southward. During the day, they scattered as they fed but then came together in the afternoon, the haphazard drift becoming a purposeful march. Far beneath us, the many mile-long mass seemed to glide across the tundra, skirting lakes and bunching into tight brown clusters at rivers and narrows. The sun was setting. The land beneath lay somber, its myriad glittering lakes reflecting the copper sky. Over the dark earth snaked the vast throng of migrating caribou, a golden ribbon of life in the sun's slanting rays.

Later, in Tanzania, I flew high above the Serengeti, that immense grassy plain that is home to Africa's largest wildlife herds. Most wildebeest had given birth within a two-week period, and now brownish long-legged calves were trotting near their mothers. The herds, consisting of more than a million wildebeest, were marching northward in search of greener pastures, following their age-old migration trails.

Some concentrations of animals, such as fur seal colonies, were discovered centuries ago. Others have only recently been discovered. In 1963, National Geographic published an article entitled "Mystery of the Monarch Butterfly." The mystery concerned the whereabouts of the monarch's winter roosting grounds. Twelve years later the mystery had been solved and National Geographic published: "Discovered: The Monarch's Mexican Haven." A few years later I visited this butterfly haven high in the Sierra Madre Mountains,

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFirefly Books

- Publication date2002

- ISBN 10 1552976661

- ISBN 13 9781552976661

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages256

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Glimpses of Paradise: The marvel of massed animals

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # DADAX1552976661

GLIMPSES OF PARADISE: THE MARVEL

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 3.09. Seller Inventory # Q-1552976661