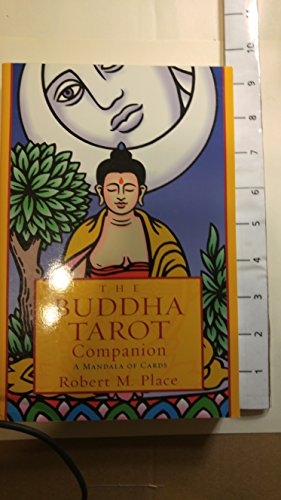

Items related to The Buddha Tarot Companion: A Mandala of Cards

In this companion guide to The Buddha Tarot, artist and writer Robert M. Place, who drew parallels between Christianity and the Tarot in the Tarot of the Saints, now applies his unique vision to connect the Eastern and Western spiritual experience.

This book examines the history and development of Tarot, from its roots in the Middle Ages to its myriad modern incarnations. The author also delves deeply into Western mysticism and philosophy, showing how Platonic and Neoplatonic thought influenced centuries of Western magic and mysticism. He then examines Buddhism from a Westerner's point of view, including a description of the Buddha's life and an in-depth look at the themes represented in traditional Tarot and their parallels in Buddhist teachings. The Buddha Tarot Companion also includes a detailed description of each card and its symbolism, and how each card in this unique deck relates to the Tarot tradition.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Life of Buddha

The legend of the life of Buddha has many variations. Even the date of

his birth is disputed. In China, he is believed to have been born in 947

BCE, but elsewhere the most commonly given date is 563 BCE. At

birth, he was given the name Siddhartha, and his family name was Gautama.

He is also called Sakyamuni, which means “the sage (-muni) of

the Sakya clan.” Buddha is a title, not a name. It means “one who is

awake.” To the Buddhists, a Buddha is no longer a person. It is a different

category of being―not a mere god, but a being superior to a god.

The following account is a popular version of Buddha’s life, focusing,

as do the Buddhist texts, on Siddhartha’s early life and his heroic

quest for enlightenment. The oldest Buddhist texts were written in the

first century BCE in Pali (an ancient language of northern India close to

the language that Siddhartha spoke), although the oldest copy of a Pali

manuscript that we actually have today is about five hundred years

old.1 These stories are more concerned with symbolic significance than

an accurate account of Siddhartha’s life. Later a more complete biography

was written in Sanskrit.

In the Pali texts and the subsequent Sanskrit texts, we learn not only

of Siddhartha’s life, but also of his past lives and of the twenty-four

Buddhas who preceded him in other ages. At one time in a past incarnation,

Siddhartha was a Brahman named Sumedha, an ascetic who

came into the prescience of the first Buddha, named Dipankara. Like

all Buddhas, Dipankara had the power of clairvoyance, and seeing

Sumedha in the midst of the assembled crowd, he announced that one

day Sumedha would also become a Buddha. This event set Siddhartha

on his spiritual path, and led to his eventual Buddhahood. In the following

547 incarnations, Siddhartha experienced life as a lion, a snake,

and other animals, as well as a human. During this process he purified

himself and perfected the ten virtues: generosity, morality, renunciation,

intelligence, energy, patience, truthfulness, determination, benevolence,

and equanimity. He became a Bodhisattva, a title that refers to a person

on his or her way to becoming a Buddha, and he incarnated in

Tusita Heaven with the gods.

Tusita Heaven is a paradise above Mount Meru in the sacred center

of the world. The beings that live there are gods, but in Buddhist theology,

the gods are not immortal. Although their lives are so long that

they seem immortal to us, they, too, will suffer death. Of the six worlds

shown on the Wheel of Life mandala, Tusita is the best place in which

to incarnate. Realizing that his time there was ending, Siddhartha knew

that it was time to incarnate in the world of men and to take the final

step that he had been preparing for throughout all of his past lives: to

become a Buddha.

Siddhartha was born on the full moon in Wesak (our month of May),

although the Chinese fix his date of birth on our modern calendar as

April 8. He was born in Kapilavastu, a principality that no longer exists

but which included an area that is now encompassed by northern India

and Nepal. His father and mother were Suddhodhana and Maya, the

wealthy rulers of Kapilavastu. They were members of the Ksatriya caste

(the noble or warrior class).

Before Siddhartha’s birth, Maya had a dream in which she was visited

by a white elephant with six tusks. In the dream, the elephant impregnated

Maya by piercing her side painlessly with one of his tusks. Ten

lunar months later, Siddhartha was born. After his birth, it is said that he

immediately stood and a white lotus rose under his feet from which he

surveyed the ten directions. He then took seven steps toward each of the

cardinal directions, and declared this to be his final birth. In some versions

of the story, Suddhodhana and Maya had not yet consummated

their marriage when Maya became pregnant. Therefore, Siddhartha’s

birth, like that of Jesus, was from a virgin. Seven days after Siddhartha’s

birth, Maya died of joy and ascended to Tusita Heaven. Maya’s sister,

Mahaprajapati, married Suddhodhana and raised Siddhartha.

A short time later, a seer named Asita, a saintly old man from the

Himalayas, came to visit the child and confirmed that two possible destinies

awaited him. If Siddhartha embraced a worldly life, he would

grow to be a chakravartin (literally, “a wheel-turner”), a great emperor

over a unified India. If he embraced asceticism, he would become a

world savior―a Buddha. Asita was sure that Siddhartha would take

the religious path.

As the child was growing, his father summoned a council of wise

Brahmans (members of the priest class). They determined that Siddhartha’s

destiny hinged on whether or not he beheld the four sights:

old age, sickness, death, and the life of the holy hermit. Suddhodhana

wanted his son to succeed him to the throne and become a powerful

ruler instead of an ascetic, so he kept Siddhartha in a beautiful palace

with sumptuous gardens and delightful young women to serve as his

attendants or as his courtesans. Some accounts say that the palace was

surrounded by three walls; others say that it was surrounded by four

gardens, one for each of the four directions. All accounts agree that the

sight or even the mention of death or grief was forbidden.

The young, charismatic Siddhartha excelled in the martial arts and

in his intellectual studies. He was the perfect example of his caste, even

surpassing the knowledge of his teachers. When he was sixteen, his

father encouraged his marriage to the beautiful princess Yasodhara. To

win her, Siddhartha had to enter a competition of martial arts. He won

by stringing and shooting a perfect arrow with his ancestral bow, a

bow that most men could not even lift. After this, Siddhartha became

enchanted by the delights of marriage, and his father felt secure that his

son, having been conquered by love, would follow the worldly path.

However, this enchantment did not last. The young man grew restless;

his life of sensual pleasure began to appear shallow and vain.

Motivated by a desire for greater knowledge of the world, Siddhartha

decided to leave the palace and prepared to visit the city in his chariot.

His father, worried about what Siddhartha would find there, had the

entire city swept clean of any unpleasantness. But the truth prevailed

after all. Siddhartha saw an old man, bent, trembling, and leaning on

a cane―the first of the four sights that had been predicted by the

Brahmans. The young man had never seen someone that old before,

and it taught him that decrepitude is the fate of those who live out

their lives.

On his second visit to the city, Siddhartha came across a man suffering

from an incurable disease. On his third visit, he saw a funeral procession

carrying a corpse. Through these experiences, Siddhartha

learned that all human lives eventually include suffering and death, and

that it is the fate of humanity to repeat this suffering again and again

during the seemingly endless rotations of the wheel of reincarnation.

On his fourth and final visit to the city, Siddhartha met a sadhu, a

holy hermit, who wandered through the country carrying a begging

bowl. Despite his poverty, this man was calm and peaceful. It seemed

to Siddhartha that this man offered him a path out of the torment that

the other sights had caused him. He returned to the palace with hope.

After his son Rahula was born, Siddhartha realized that his obligation

to continue his royal line had been fulfilled. With great strength

and determination, he prepared to leave the palace and seek enlightenment

by becoming a sadhu. One night while his family slept, he rode

out on his faithful horse, Kantaka, determined not to return until he

reached his goal. He gave Kantaka to his equerry, cut off his hair, and

exchanged his splendid robes for those of a hunter.

Siddhartha’s quest for enlightenment moved through three phases.

First, he wished to attain wisdom. He sought out two of the foremost

Hindu masters of the day and learned all he could from their tradition,

including the discipline of meditation.

In the second phase, Siddhartha decided that the desires of his body

were holding him back. To crush his body’s interference, he joined a

band of ascetics. In that time, sadhus were known to practice severe

austerity, but Siddhartha outdid his teachers in every discipline and

gathered five disciples of his own. In a final effort to attain victory over

his body, he went on a prolonged fast. Eventually, he turned himself

into a living skeleton, but this still did not bring him to his goal. Siddhartha

saw that asceticism was as futile and as egotistical as sensuality

―neither would bring an end to suffering. He began to eat and build

up his strength. When a village girl named Sujata offered him a bowl of

rice and milk, he accepted it. After his meal, he bathed in the river. In

that time, several practitioners of Jainism had fasted themselves to

death in an effort to gain liberation and Siddhartha’s disciples hoped

that he would do the same. When he began to eat, his disciples left him

in disgust.

Now Siddhartha entered the third and final stage of his quest. He was

inspired to follow the Middle Way, a path of balance between the

extremes of denial and indulgence. He wandered alone until one evening

he sat down under a fig tree (later named the Bodhi Tree, which means

“the tree of enlightenment”). Here, he entered into a state of deep mystic

concentration and vowed not to rise until he had attained his goal.

Mara, the Evil One, king of the demons called maras, realized that

Siddhartha was nearing his goal. If Siddhartha could find an end to suffering,

this would be a threat to Mara’s power, and he was determined to

interfere. First, Mara sent his three voluptuous daughters, Lust, Passion,

and Delight. Having overcome his attachment to sensuality in his life as

a prince, Siddhartha was immune to their temptations. Next, Mara tried

to frighten him by sending an army of demons equipped with an imaginative

array of sadistic weapons. However, Siddhartha’s life as an ascetic

had made him immune to fear of bodily harm, and, as the demons

approached, they found themselves halted. Siddhartha had ceased to

echo emotions like fear and anger, emotions that the demons needed to

feed on. In place of these emotions, they found only compassion. As the

demons entered Siddhartha’s aura, they became calm and peaceful and

simply bowed down before him.

Mara made the final attack himself. Riding on a cloud, he hurled his

terrible flaming disk at Siddhartha. Yet this weapon, which could cleave

a mountain, was useless against Siddhartha. The disk transformed into

a garland of flowers and hung suspended above Siddhartha’s head.

Mara was beaten. In a last effort, he challenged Siddhartha’s right to

do what he was doing. Siddhartha merely touched the earth with a finger

of his right hand, and, in a voice like thunder, the earth answered,

“I bear you witness.”

It was Wesak, the night of the full moon in May. During that night,

Siddhartha entered into the initial stage of enlightenment. For the first

time, he could see the entire wheel of rebirth, including all of his past

lives. He saw the suffering of all living creatures, and then the means to

end that suffering. He realized that as long as he tried to find the way

to his salvation or his enlightenment, he was still trapped in his ego. It

was only when he replaced all concern for himself with total compassion

that he was free. When he did this, he was no longer a separate

ego and he and the world became one. As the sun rose, Siddhartha was

fully enlightened―but he was no longer Siddhartha. He was now Buddha,

which means “the awakened one.”

Buddha remained in meditation for another seven days before rising

from his seat. He remained near his tree for several weeks. Then he realized

that before he could proceed, he had to make a decision. Two paths

were open to him: he could enter Nirvana at once, or he could renounce

his own deliverance for a while in order to remain on earth and spread

his message. Mara, of course, urged him to enter Nirvana. Mara argued

that people are ignorant and incapable of understanding Buddha’s wisdom

and that Buddha should leave them to their own devices. After

some initial hesitation, Buddha had a vision that helped him realize that

this was the final trick of the ego. To enter Nirvana at once without

thought of others who were in need of his teaching would mean letting

go of the very compassion that had brought him this opportunity. There

was only one answer. Without further hesitation Buddha said, “Some

will understand.” Buddha remained on earth to teach and to become an

embodiment of wisdom and joy in the world.

Buddha’s first sermon, in a place called Deer Park, was to the five

disciples who had previously deserted him. They were quickly converted

to his new teaching. Over the next half-century, these five disciples

became the nucleus of a monastic community that grew to include

both men and women from all classes of society. Buddha’s parents, his

wife, his son, his half-brother, and even his cousin became his disciples.

Everywhere Buddha went he made converts, and his teachings reached

countless individuals. This oral tradition provided the foundation for

the scriptures of Buddhism, the sutras. It was only after reaching the

age of eighty that Buddha died. He was accidentally served a poisonous

meal (some say it was mushrooms; others say pork). His last words

included:

All compounds grow old.

Work out your own salvation with diligence.2

After his death, Buddha passed into the bliss of Nirvana.

The Four Noble Truths

We may wish that we were at that first sermon in Deer Park when it is

said that Buddha set the Dharmachakra, the Wheel of the Law, in motion.

What was this teaching that has had such lasting value for over two thousand

years?

By calling the teaching a “wheel,” Buddhists created the symbolic

equivalent to St. Ambrose labeling the four Platonic virtues “cardinal.”

They were saying that the teaching, like Plato’s four cardinal virtues,

was capable of overcoming the wheel of fate or the wheel of reincarnation.

Like the virtues, this first sermon had a fourfold structure. It is

called the Four Noble Truths and they are listed as follows:

I. All life is dukkha, a word usually translated as “suffering.” In

Buddha’s time, dukkha described a wheel whose axle was bent or

off-center. By this Buddha was not saying that life is continuously

painful, but that all lives contain some pain and suffering. Buddha

pinpointed four principal moments when this is true: at the trauma

of birth, in illness, in the decline of old age, and at the approach of

death. He also spoke of the pain of being separated from what one

loves or desires, and the pain of being chained to what one does

not desire. However, even at its best, there is something shallow

and off-center about the pleasures of life. Buddha had lived like a

playboy, havi...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherLlewellyn Publications

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 1567185290

- ISBN 13 9781567185294

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages384

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Buddha Tarot Companion: A Mandala of Cards

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1567185290

The Buddha Tarot Companion: A Mandala of Cards

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1567185290

The Buddha Tarot Companion: A Mandala of Cards

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1567185290

THE BUDDHA TAROT COMPANION: A MA

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.3. Seller Inventory # Q-1567185290

The Buddha Tarot Companion: A Mandala of Cards

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB1567185290