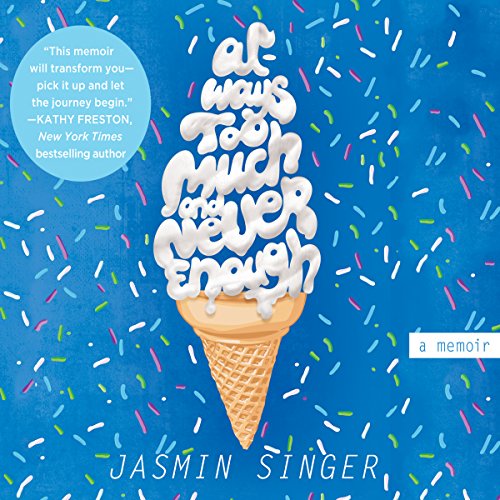

Items related to Always Too Much and Never Enough

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

I

what i lost

ONE

let’s do this

That bathroom stall was ridiculously small. I wriggled my way around, trying to wedge both me and my stupid, gigantic purse into the cramped rectangle. I shimmied, did a tiny pirouette, and finally edged my pants down. It was like Swan Lake in there, and all so that I could successfully maneuver my 221-pound, five-foot-four self into proper peeing position.

“This is like a goddamn gestation crate,” I said to no one in particular, finally finding a suitable stance, but only after banging my funny bone on the sanitary napkin disposal.

A few minutes later, as small beads of sweat collected on my forehead, I washed my hands, thinking, “Why is soap in public bathrooms always hot pink?”

I was winded. I decided to take a moment to catch my breath. My dining mates could wait. They were probably in a tabbouleh daze by now anyway, busy working their way through the fava bean appetizer.

Oh, how I loved the food in San Francisco! Even in comparison to my own gritty city, New York—which was just bursting with flavors and cuisines vibrant and diverse enough to keep any foodie busy (including a vegan one, like me)—there was something about this town that made me hungry to try everything. On that night, my partner, Mariann, and I had met up with a couple of friends who knew the ins and outs of the restaurant scene in the City by the Bay. They’d chosen a slightly gaudy, but nonetheless mouthwatering, Mediterranean restaurant in the Tenderloin district—ironic, because we were there for its scrumptious vegan menu. The only tenderloins in our lives were made out of wheat gluten.

Just before I excused myself to go to the bathroom, my friends John and Cassie had been telling Mariann and me (but mainly me) about a new documentary, Fat, Sick & Nearly Dead, set to be released the following spring. John and Cassie worked in magazine publishing and had been given an advance press copy.

They told us that the film was about a man who juice fasted for sixty days in an effort to get his health back. As he flooded his body with fruits and vegetables, he lost a tremendous amount of weight, got off all his medications, and cured a debilitating autoimmune disease that had plagued him for years. “You really should borrow it, Jasmin,” John told me, a bit too adamantly for my taste. “Seriously, you’ve got to see it.”

I fake smiled. “You know what?” I announced. “Nature calls . . .”

The truth is, when John—a naturally excited guy—shared his enthusiasm with me, I took it personally. Was his exuberance a way of calling me fat? Was he comparing me to the man in the film? When I was a kid, I had been accused of making everything about me, and perhaps there was legitimacy in that still. But this hit pretty close to home.

There I was, hiding away in the maroon and turquoise bathroom instead of sitting beside my girlfriend enjoying the company of my good buddies and eating incredible food. I suddenly felt a twinge in my right shoulder. “Dang purse,” I mumbled, shaking off the pain. What the hell was I carrying with me, anyway? I opened it up and instantly spotted the culprit: my new shoes.

And by new, I mean old. I had picked up those adorable green and white hemp sneakers at my favorite thrift store in the Mission District earlier that day. I’d forgotten putting them in my bag. Satisfied that I wasn’t suddenly suffering from brittle bones, I fished out a lip gloss.

And then, unthinkingly—before having the foresight to prepare myself—I foolishly looked at myself in the mirror.

It’s amazing, really, how easy it is to master the art of looking in the mirror without actually looking at yourself—in a way that doesn’t make you want to step in front of a bus, that is. I knew all the tricks: how to hang mirrors a few inches too high so my view of myself was always from the way-more-flattering angle above; how to suck in my cheeks just a little bit to give myself fake cheekbones, widening my eyes at the same time to add to the effect; and, finally, how to look at only one part of my body at a time—my eyes if I was putting on shadow, the crown of my head if I was brushing my hair.

Even a simple act like walking down the street with a friend was like a real-life video game. The challenge? To keep the conversation going while avoiding, at all costs, catching a glimpse of my reflection in a window—an image that echoed the truth in ways I was not prepared to handle. And so, rather than take the chance of spotting my silhouette, I would maintain unrelenting eye contact with my hapless companion, who was no doubt wondering why I seemed to be trying to peer into his or her soul. Anything to avert my eyes from the truth, to remain in the dark.

It had been a good number of years, in fact, since I had looked at myself, head-on, in full, with no preparation—with no absurd rationalization of what I was about to see, of who I was about to see.

Except, this time, I acted too quickly and, as I stared at myself in the bathroom mirror, I accidentally saw it all: my three chins, my blazer that didn’t close, and my Humpty Dumpty figure. Just like that, there I was, without my mirror-face on to protect me.

I was alone in the bathroom, with only myself and my cracked veneer, and yet I was self-conscious, somehow feeling as if I were being watched. My stomach ached, and not because of the numerous triangles of perfectly browned pita bread I’d just eaten. I needed an escape, fast. Just as it started to dawn on me that the intensity I was feeling was my own DIY wall of denial beginning to crumble, I randomly spotted a plastic earring on the floor that someone must have dropped. That one-earringed person was clearly my angel, because in that moment, that plastic earring saved my life—or at least my evening—giving me the distraction I needed to pull myself together.

“Stop feeling sorry for yourself,” I quietly commanded. Self-pity was simply not an option. Wallowing should be reserved for people who were truly without. I had no right to be upset just because I was fat.

“Focus on what you’ve got right,” I whispered. Like my thick-framed blue and white glasses, which I had bought at Fabulous Fanny’s in the East Village, or the two dozen glittery barrettes that decorated my spiky black and pink hair. I had “a look”—that was what people had told me my whole life—and as my weight stepped up, so did my many ornaments. I had always assumed that my eyeliner diverted attention from my bulbous belly and that my nose hoop distracted from my self-consciousness.

And yet, in spite of the temporary respite provided by the lost earring and my standard pep talk, all my warts were still right there, smack in front of me, staring back. At that moment, a familiar, happy thought occurred to me: I was fairly certain that the overwhelming sense of despair that was always lying dormant in me, and that was starting to bubble up right at that instant in the ostentatious bathroom in the Tenderloin, would be effectively cured by spinach pie.

So I put on lip gloss without watching and headed back to my booth, where the all-knowing Mariann shot me the “is everything okay?” look, and I smiled another fake smile—all the while knowing she wouldn’t buy the bullshit and we’d have to hash it out later. She was, after all, one of the realest parts of my life—the part that grounded me when the whole world seemed out of control.

“There was a wait,” I lied, a little too exuberantly.

And then—Jesus Christ!—it was as though my dining mates had paused the clock and stared into space while I was in the bathroom, counting the seconds until I returned to the booth just to pick up the conversation exactly where we had left off. My abrupt exit had been dramatic only to me. Next time I’d have to try harder.

“So, as I was saying,” John said as he wiped a dollop of hummus from the right corner of his lip. “You’ve gotta see this movie, Jazz.”

Cassie agreed. “You’ve gotta. It’s a game changer.”

A game changer.

When I stepped onstage for the first time in first grade and realized that I could be anyone in the world up there, and maybe I’d be accepted, because I was good at it, and I could be someone else while I was center stage—that was a game changer. When I slept with a woman for the first time, at nineteen, that had been a game changer (especially for my then boyfriend). When I learned, at twenty-four, that the food industry was lying to me, and I went vegan—a decision that shaped me, gave me the kind of fulfillment that many people my age only dreamed of having, and added deep and profound purpose to my life—a game changer indeed. When, at twenty-seven, I met Mariann, and together we decided to try to change the world—game changer.

I knew a thing or two about changing the game.

I held my breath, wanting so badly to talk about anything besides a man who was fat and sick and nearly dead. A man to whom my friends were obviously comparing me.

Sometimes change comes merely as a result of hearing something at exactly the right moment. Sometimes, like a pair of perfect hemp sneakers at a secondhand store, you have no idea what’s about to enter your life.

Given the conversation about the documentary that my friends insisted I “really had to see,” it seemed a remarkable coincidence that I had just read an article about juice fasting and, much to my surprise, had found myself intrigued.

The waiter placed my dish in front of me. “The spinach pie, miss.”

My belief that spinach pie would distract me from the thoughts that kept bubbling up proved wrong. In spite of the deliciousness that sat right there in front of me, I could no longer refuse to notice the lingering back and shoulder pain that I felt every morning, the rashes I got on my thighs from flesh rubbing against flesh, the deeply buried sadness and anger that hid behind my days. There were only so many glittery barrettes.

My shoulder twinged again—I was used to being achy. Even though I was only thirty, it was difficult for me to go up a flight of stairs without stopping halfway to rest. Sometimes I stopped in the middle, pretending I needed to adjust the cuff of my jeans, or check a pretend text, just to buy some time before finishing the exhausting trek. Why did I feel like shit all the time? I was young, vegan, and even had a master’s in health and healing. And yet, I was digging myself an early grave. It was embarrassing.

Even though I rationalized my weight by saying that my life of abundance—decadent food on a consistent basis, several soy lattes a day, wine each night—was a way to repay myself for the hard work I did, the truth was that I knew I was hurting myself. The even deeper truth was that I was addicted, and rationalization is the oldest tool of the addict. Even when the results from my physical came in and I was told, point-blank, that my weight and cholesterol were issues that I needed to pay attention to, I still rationalized. They weren’t big concerns yet, I said, and I’d deal with them if and when they became issues.

As I stared down at my spinach pie, I couldn’t help but wonder when exactly that moment would come and I would begin to take responsibility for my health.

Cassie, true to form, was now animatedly discussing the newest cashew cheese to hit the market. It’s difficult to find more passionate foodies than a group of vegans. My dining mates and I had seen the dark, early days of bad vegan cheese, so we felt we were allowed a little over-the-top excitement on the matter.

I interrupted. “Hey, you guys?” I said, suddenly self-conscious, yet trying—as always—to seem unflappable. “I think I’ll borrow that movie you mentioned, if that’s cool. The one about being fat and sick?”

“Yeah, sure!” John beamed. “Pick it up from my office tomorrow.”

—

After I picked up the movie and went back to my hotel room and watched it—immediately, on my laptop, with Mariann beside me—everything came to a head. All of it—the lies, the sadness, the rationalization, the heavy heart, the sometimes misdirected anger at the world and at myself—it all culminated in one surprisingly simple, subtle shrug.

“Let’s do this,” I said.

In retrospect, I am not sure precisely what I meant by “let’s do this.” It seems to me I was trying to say, “Let’s do a juice fast. Let’s lose weight. Let’s get healthy.”

But by “doing this,” I wound up committing to a whole lot more than I’d be able to grasp for years to come, and in some ways am still trying to grasp, and maybe always will be. It took losing nearly one hundred pounds for me to start to understand what I was, in fact, “doing.” And perhaps more importantly, what the world was doing to me.

The world was, I would later find out, interested in my size to a much greater degree than had ever occurred to me. Because it was only when I lost the weight and my body suddenly seemed to suit the narrow definition of “acceptable”—slim, svelte, slight—that I started to experience what it felt like to be propelled upward by the same society that had previously seemed to prefer that I just disappear.

Prior to that proclamation, “Let’s do this,” I would have told you that I already had a meaningful understanding of the food I ate and the way it affected me and the way it affected the world. I would have theorized that the reason I had always felt as if I was going up the down staircase was because I was offbeat, or because I was an individual thinker, not because I was fat and therefore deemed unworthy by society; not because I was a food addict who was battling shame issues as steadily as I was battling bullies. I ate and lived in a way that was in harmony with my worldview, and I loved that. That had been good enough for me, until suddenly it wasn’t. And when it wasn’t anymore, that was when something permanently shifted. That was when it became abundantly clear to me that simply eating in a way that avoided hurting others was never going to be enough if my eating habits were still hurting me.

So when I started shedding the weight and reclaiming my health, it was quite a shock to learn that, in order to truly live genuinely, I had to confront how I had been betrayed by a food industry that relied on my willful ignorance and by a society that relied on my undiscerning willingness to buy into its arbitrary notions of self-worth and beauty.

I see now that it was that dinner with my friends that was the turning point. It was the warm decadence and safe reassurance of the spinach pie—that suddenly didn’t seem so safe. It was John’s persistent vehemence that I just had to watch that documentary. It was Mariann gently squeezing my knee under the table, reminding me that I wasn’t alone, that she was beside me. That this was real. That I was real.

It was standing in a bathroom stall, unable to turn around because the walls were closing in on me. It was accidentally catching a glimpse of myself in that bathroom mirror, witnessing in real time my own vulnerability, my desperation, my heaviness. It was knowing in that moment that outside of the bathroom of that restaurant in that city was an entire universe—and in that universe, ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherDreamscape Media

- Publication date2016

- ISBN 10 1682629910

- ISBN 13 9781682629918

- BindingAudio CD

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want