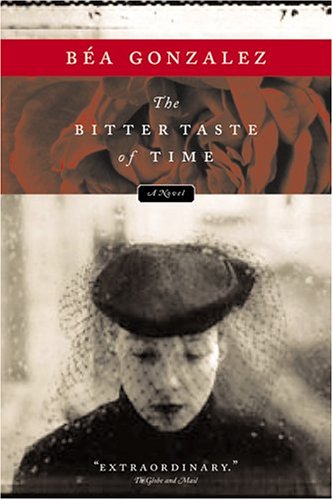

Bitter Taste Of Time Reissue - Softcover

Can you believe the things that happen to those Encarna women? No family in the small Spanish town of Canteira has ever given the gossips so much to talk about, so many tragedies and disasters to share on long winter nights. After the absurd but tragic death of her husband, María Encarna, the family's imposing matriarch, turns her granite house into a pensión, opening it up to strangers with their colorful stories of demons and wars.

The pensión is very much a woman's world: there's María, known as María la Reina - the Queen - because of her haughty manner and legendary beauty; María's two unmarried sisters, Cecilia, given to daring culinary experiments and endless melodrama, and Carmen, the Holy One; and María's two daughters, Matilde, lost in a world of the imagination; and Asunción, a great beauty and her mother's favorite - until she marries Manuel Pousada, the town's most notorious sinner,whose true motive is to get closer to the disdainful María, the unwilling object of his perverse longings.

Fueled by the profits of her connection with the contrabandistas, María builds a 50-bed hotel and cafe-bar. Through the Spanish Civil War, a dictatorship, and the beginning days of the new democracy, the Encarna women, now joined by Asunción's entrepreneurial daughter Gloria, become the wealthiest family in the town. Yet despite their success and tenacity, tragedy comes calling, usually in the form of a man'and almost always on a Friday.

In the tradition of Like Water for Chocolate and Antonia's Line, The Bitter Taste of Time is a wondrous, rich and romantic tale of a sweeping history that belongs to a family of remarkable women, a story of passion, pride, love, and war. By turns funny, tragic and touched with a fine sense of magic realism, The Bitter Taste of Time is a hugely entertaining read.

Béa Gonzalez's work has been published in The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star, T.O. Magazine and Brick Literary Magazine. She has been a finalist twice in the CBC/Saturday Night literary competition. Béa Gonzalez spent several years in Galicia, Spain, while growing up and now lives in Toronto

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

BÉA GONZALEZ

was born in Vigo, Spain, and immigrated withher family to Canada as a child. Following studies in Spain and in Toronto, shecompleted an M.A. in European literary and historical studies at King’sCollege, University of London. Gonzalez also develops and leads cultural toursto Spain and Latin America to study the works of their poets and writers.PART ONE1920-1930LATER, AFTER YEARS HAD PASSED AND THEY ALL HAD THE benefit of hindsight, they would comment on how truly strange Asunción Encarna had been from the start. A curious bird. As unpredictable as a goat. As peculiar as all those foreigners who arrived on the coasts of Spain dressed in gingham shorts and knee-high socks.The roots of this peculiarity--the one that years later would have her collecting clocks in all shapes and sizes--they traced back to the events at the train station on a Friday in 1920. It was there that her husband of two short months, Manuel Pousada--a lunatic himself, one was quick to comment, a criminal of the worst kind, another added--aware that gossips loomed all around them and eager to avoid a scene during these, their final moments together, had tried in vain to stem her tears, silence her pleas, keep her from making a public spectacle of herself.But then, he never loved her, they would say later. No, not for one moment did he seem sad to leave her.Manuel Pousada and Asunción Encarna were at the station that day so that Manuel could take the train to the coast. From there, he would be boarding the ship to Brazil. Brazil. Howlong he had waited for this. The word rested sensuously on his tongue, the thought of it seemed like heaven. His wife's tears, her adolescent tantrums, jarred him now that the dream seemed so close at hand, now that his mind was already lost in the thought of much better things, on the stories he had heard from all those who had gone before him and had returned with gold and women and especially with the heat--sí, especially the heat, which they captured and brought back with them, and which glinted in their eyes and shone in their hair and glowed in their habit of walking with erect shoulders forever after.And then one more kiss, one last backward look, a shake of the head, and he was gone, into the train and away from her life. And more tears and more anguish, and the promise--Cariño, he had said, it is only a matter of time now.It would indeed be a matter of time before Asunción heard news of him, and then only after showering a mountain of abuse on the archaic and inefficient postal system of the region and the half-witted man in charge, who cried real tears of desperation because of it. When the letter finally arrived, she shared its contents with no one, stopping only to fold it neatly into its four parts once it had been read and announcing to all that her husband had now joined the ranks of the dearly departed.Three months later, in August of 1920, after a long day and an even longer night, their daughter Gloria was born. In the room with Asunción, accompanying her through every heave and every push, were her mother María, her sister Matilde, and her aunts Carmen and Cecilia. There too was Doña Emilia, the town's midwife, and the two old women who accompanied all of the women in Canteira through the mysteries of labour, Doña Teresa and Doña Elena--greatly respected for having delivered eight healthy babies apiece, and eager to tell the storyof each of those births as a way of reminding everyone that childbirth, fraught with so many dangers, could as often as not produce healthy, happy children.Outside, the town of Canteira was as silent as the stars with only the occasional sound rising here and there to punctuate the night--the whelp of a dog, the gasping spasms of a donkey, the odd distant and disembodied voice emerging from the hills which appeared purple and bruised in the encroaching darkness. It was a hot night, one of the hottest of that year. The large windows in the bedroom had been left open, but the warm breeze that drifted in did little to alleviate the oppressive humidity. For months before the birth, Asunción had remained closeted in this room, grieving for her dead husband and praying for the health of her unborn child. There, at least, she was thought to be safe from the many dangers that lurked outside, like the moon--the source of inspiration to many a haunted poet, but which pregnant women avoided, believing that to look at it would be to risk giving birth to an idiot.As the labour progressed, and Asunción's screams grew shriller, her discomfort greater, Doña Teresa and Doña Elena interrupted their stories to implore the midwife to take some extraordinary measures.Bring us a pair of her husband's pants or one of his hats, Doña Teresa said between two particularly strong contractions. There is no surer way to calm the pain than with some of the father's clothing. May he rest in peace, she added quickly, crossing herself as she did so.A prayer to San Ramón will do the trick, Doña Elena said. The prayers I myself uttered can scarcely be counted.María, Asunción's mother, an imposing woman with little respect for the sayings of the people, for all the crazy ideas thatcirculated through town, the fears of the dead and the superstitions that held so many hostage, dismissed the suggestions of these women with an impatient wave of her hand.She turned now to her sister Cecilia--a nervous, emotional woman, who would punctuate every contraction and accompanying scream with a furious Dios mío--ordering her to boil some more water in the kitchen--a command she issued more to rid the room of her sister than because any water was actually needed.Later, it would be Cecilia who would tell the story of the birth, exaggerating and embellishing the details to such an extent that eventually no one who had been there could distinguish between what they could remember and the inventions of Cecilia's feverish mind. What was true, irrefutable because it had become a part of the history of the town itself, was that Gloria had been born into a world full of women. It was not only that her father had perished in an unimaginable and distant land before her birth, but that he had left his wife behind in the care of her mother, two aunts, and a younger sister. What was also true was that Asunción had almost perished from the effort, all the pushing and the pulling, all the tears, all the desperate screams. The screams had been heard, in fact, as far away as the region of Castile--this, again, according to Cecilia, who had held Asunción's hand through most of the ordeal, attempting to ease her pain by forcing almost two full glasses of aguardiente into her mouth, but carefully, one drop at a time, until Asunción had grown drunk and delusional from the devastating combination of liquor, longing and pain.It is during childbirth that you discover love, Asunción would tell them all afterwards, once the child had been born and she was so overwhelmed with grief that she was sure she had caughta glimpse of Manuel, hovering over her like a dark, unforgiving angel. In her drunken stupor, she had slurred his name so many times and with such a deep feeling that the women had been reduced to a heap of tears and even Edelmiro, the barnyard help, who had never loved and never lost, even he had felt as if there were a hole inside his stomach too, created by the acidic vapours of such an intense and unfulfilled yearning.At least it is a girl. The child's grandmother was the first to say it. Her two sisters, Cecilia and Carmen, and her daughter Matilde had thought this too but had refrained from uttering what could only have been said by a grandmother. María said this only after her daughter Asunción had ceased crying--only after three weeks of her sobbing did María say this, and then only to bring to the house a well-needed tone of order.She had always mistrusted the child's father, Manuel Pousada. Insolent eyes; unspeakable desires. No better than a peasant traipsing into their lives, without thought or forewarning, seducing her daughter in one single furtive morning.But now there was this newborn, his newborn, a girl of white marble. Cabrón she thought uncharitably. Another man lost to the other world where he could walk unencumbered by memory or obligation. Amidst her cursing, though, it occurred to María, not for the first time, that Manuel's death had perhaps not been an altogether bad thing.Many days passed after the baby's birth before the rhythm of the house was restored to its proper order--before the women could return to the work that fed and clothed them in a world where money was always an uncertain prospect. For years the women had survived by providing room and board to the many travellers who passed through town on their way to the coast.In those days Canteira bustled and boomed with the machinations of illegal commerce. Situated in the heart of the Spanish region of Galicia, between the Atlantic coast and the border with León, the town was the resting stop for the endless stream of contrabandistas who travelled through at first on horseback and later inside Renaults and Peugeots, on their way to the coast to retrieve the goods that would be peddled in the dark cities of the Spanish interior.The country as a whole had by then fully declined into a slothful decay. One by one, the colonies that remained in the Americas had reclaimed their independence from the incompetent central government of Spain. After 1898, all that remained were bitter words scribbled by a generation of writers bleeding their shame into the gaping wound the colonies left in their wake. All Spain could boast of now were greedy landowners, fattened Jesuits, disgruntled miners biding their time till they could stand up against the owners of the fetid hellholes where they worked themselves into an early grave.In Galicia things were worse. Long forgotten by the central powers of Spain, no easy path led people to th...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHarper Perennial

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0006393233

- ISBN 13 9780006393238

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages247

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 3.49

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Bitter Taste Of Time Reissue

Book Description paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_389689123