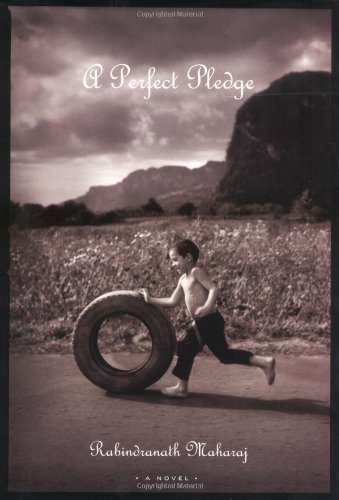

A Perfect Pledge: A Novel - Hardcover

In A Perfect Pledge, Maharaj combines a Dickensian rendering of the effects of poverty, caste, envy, superstition,corruption and bigotry with vivid, complex characters and gorgeous writing, in a novel that celebrates both the resilience of the human spirit and the heartbreak of failed dreams.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

On the evening the baby was delivered by Mullai, the village midwife, a chain-smoking dwarf who smelled of roasted almonds, cumin, and cucumber stems, Narpat, who was fifty-five years old and had given up the idea of fathering a son, was sitting cross-legged in the kitchen methodically compiling one of his lists: ginger, saffron, sapodilla, pineapple, avocado, coconut jelly, and sikya fig, a small banana found in all the birdcages in the village. Narpat had pored over his list for more than an hour, adding new ingredients and crossing out others. Finally, satisfied that he had achieved a balance between restorative and purgative items, he untwisted a long piece of copper wire from a nail on the wall and stabbed the sheet so that it lay atop a jumble of yellow dietary clippings he had pinched out of newspapers and magazines. Over the years the nail had accumulated scores of lists, most detailing dietary stipulations, but others an odd blend of injunctions and affirmations, and in miniature scribbles, baffling classifications: Small men with cracked skin who eat quickly and suffer from sleeplessness, accumulate and waste money quickly. Fat men with oily skin and a bad body odour are slow in decisions but fast in temper. Men with a medium body and small, light eyes are enterprising but faultfinding.

The groceries and fruits were for Narpat, who had calculated, typically, that neither mother nor baby would have much appetite for the next few days. He strung the wire on the nail and returned to the wooden bench, the Pavilion, drawing up both his feet and tracing the veins that ran along his calves to his ankles. When he heard the midwife alternately berating his wife in Hindi and encouraging her in English, he got up, walked to the small wooden porch, and leaned over the railing.

He had single-handedly built the house when he moved from Piarco to Lengua in 1926, thirty years ago, and it had been constructed in the simple style of that time: a boxy, threadbare structure with a roof of corrugated aluminum and walls of unpainted cedar and toporite. “People who live in painted houses,” he would tell his daughters, “just playing with fire. The toxic fumes that outgassing bit by bit, will breed bloating and brain fog. Then they will blame these complaints on obeah or maljeau or jadoo. People in this country have a thousand different reasons for every simple thing. It make them smarter, they believe. Like little children trying to understand how a toy operate.”

There were other unmistakable traces of Narpat’s hand in the design. The front of the building was elevated about three feet from the ground with thick, stubby mora logs, but the posts at the back were shorter, or had sunk, so there was a slope all the way to the kitchen. Occasionally Narpat grumbled about the water from the kitchen sink – in reality, a ledge projecting from the back window – spilling over and softening the post’s foundation, but at other times he maintained that the decline would strengthen the calf muscles, enhance balance, and tone up circulation. He told his daughters stories of loggers in Canada balancing on massive trees in the rivers and of sailors from around the world sword-fighting on tilting vessels. Transforming the house’s defect into a romantic fancy, he sang, “Our own little ship sailing to the Azores, laden with pepper and spice.”

The inside of the house was as bare as a ship’s deck too. The small front porch, enclosed by shaky wooden bars knocked into a split railing, led to the dining room, its floor built with uneven mora planks so the children could peep through the gaps at the rusted tools and aluminum sheets their father had, over the years, lodged beneath the house. There were spaces on the walls too, which his wife Dulari had tried to cover with the calenders she got every Christmas from the Chinese grocer. Whenever she complained that the cedar, hollowed by termites, was paper thin in some spots, Narpat would grin at his three daughters hunched over the low table and weave the almanac pictures of hollies and watchful deities and kittens into implausible stories. When he was finished, he would call one of his three daughters, Chandra, Kala, or Sushilla, to his knees and say, “Crazy story, crazy story.”

It was only with his children that his playful side surfaced; for them he had named the bench in the living room the Pavilion; and to its side, the bookcase crammed with manuals on agriculture, diseases, and construction, Carnegie. On its top shelf, enclosed by two dusty glass windows pimpled with mud dauber nests, were old Hindi texts and mysterious yellow folders. One end of the bookcase was elevated with a wedge of poui to accommodate the floor’s slant. On the other side of the wall was the children’s bedroom, with two beds jammed together and taking up half the room’s space. Sometimes late at night the girls would be awakened by their father knocking back books in the bookcase, or by conversations, usually in Hindi, from their parents’ bedroom. In that room was the only piece of furniture of any significance: a dresser with three oval mirrors and brass-knuckled handles on the wooden drawers. The dresser was a wedding present from Dulari’s brother, Bhola, and over the years the wood had warped and the varnish had raised in concentric circles, which had grown so familiar to the children, they seemed to be decorations rather than blemishes. The kitchen, the last room in the house, was a little cubicle with a chulha, a clay fireplace set at the corner and surrounded by pots and pans hanging from nails on the wall. The ceiling and the walls were powdered with soot that sometimes dropped on the floor in soft gray clumps, like dead bats. In the nights the smouldering coals in the chulha cast a dull pall on the pots and pans and on the dusty almanacs. The entire house smelled of ashes and woodsmoke, which, Narpat maintained, cleared the lungs of congestion. Just before the chulha was the door leading to Dulari’s backyard garden, with small beds of tomatoes, pepper and melongene, and machans, bamboo trellises with carailli and cucumber vines. In the centre of the garden a narrow trail of tiny white melau pebbles that glinted like scattered shillings in the night led to the latrine.

The beds of marigolds, periwinkles, zinnias, and daisies, and the poinsettia tree and the thorny bougainvillea on both sides of the porch, were also Dulari’s. The front yard was paved with asphalt, which had sunk and fragmented into irregular slabs, exposing muddy boulders beneath. To the left of the house, the asphalt had completely succumbed to knot grass, which flourished around the short Julie mango tree and the copper, a huge water basin bought from the sugar factory in St. Madeline.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0374230706

- ISBN 13 9780374230708

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Perfect Pledge

Book Description Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 19246702-75

A Perfect Pledge

Book Description Hard Cover. Condition: Like New. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. Maharaj combines a Dickensian rendering of the effects of poverty, caste, envy, superstition, corruption and bigotry with vivid, complex characters and gorgeous writing, in a novel that celebrates both the resilience of the human spirit and the heartbreak of failed dreams. Seller Inventory # 008173

A Perfect Pledge: A Novel

Book Description hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_397921895

A Perfect Pledge

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Used; Good. **SHIPPED FROM UK** We believe you will be completely satisfied with our quick and reliable service. All orders are dispatched as swiftly as possible! Buy with confidence! Greener Books. Seller Inventory # 3955229