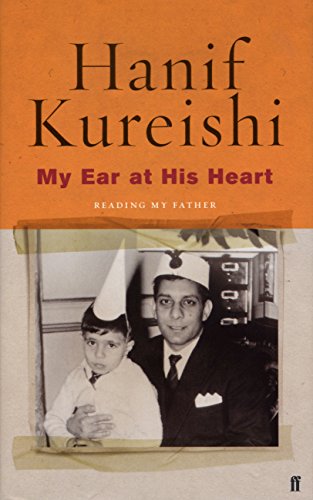

My Ear at His Heart - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

CHAPTER ONE

On the floor in a corner of my study, sticking out from under a pile of other papers, is a shabby old green folder containing a manuscript I believe will tell me a lot about my father and my own past. But ever since it was discovered I have been glancing at it, looking away, getting on with something else, thinking about it, doing nothing. The manuscript was given to me a few weeks ago, having turned up after more than eleven years. It is a novel written by my father, a legacy of words, a protracted will, perhaps ? I don?t know yet what it contains. Like all his fiction it was never published. I think I should read it.

When I first conceived the book I am now writing, lying in bed at night ? before the discovery of dad?s text ? I intended it to start with other books. I was wondering about the past as I often do now, dreaming further and further back, and thought that a way of capturing the flavour of my younger self might be to reread the writers I?d liked as a young man. I would look at, for instance, Kerouac, Dostoevsky, Salinger, Orwell, Hesse, Ian Fleming and Wilde again, in order to see whether I could rein-habit the worlds they once made in my head, and identify myself in them.

As well as being about the writers who?d meant most to me, the book would be about the 1960s and 70s, set alongside the present, with some material about the context in which the reading, and then the rereading, took place. Each book, I hoped, would revive memories of the circumstances in which it was read. It would then set me thinking about what each particular book had come to mean for me.

Whoever else was in it, I decided right away that the focus would be Chekhov?s work, his letters, plays and stories. He had been one of my father?s favourite writers, a man and doctor we discussed often. All books contain some sort of attitude towards life, and most such approaches you grow out of; like dead relationships, they no longer offer you anything. But I am still curious about Chekhov and the numerous voices his work can sustain, and often think of returning not only to his writing, but to him as a man, to the way he thought and felt, and to the questions he asked.

I came to some sort of self- and political consciousness in the 1970s, a particularly ideological time of aggressive self-description. Women, gays and blacks were beginning to speak a new or undiscovered rendition of their history. If you wanted to work in the theatre, as I did, it was impossible to escape the argument that culture was inevitably political. When Trotsky wrote, ?The function of art in our epoch is determined by its attitude towards the revolution?, the only questions for writers were: where did you stand? and, what were you doing? (You couldn?t say, what revolution? without ruling yourself out of the conversation.)

When I didn?t know what the purpose of my writing was, or when I wanted to think of what I did as an exploration of ideas and character, I?d remember Chekhov. He was a subtle writer, a supreme poet of disillusionment, suffering and stasis; and, like Albert Camus, a man who saw that being pushed into an ideological corner was of no benefit to anyone.

The book I intended originally to write would have a ?loose? form, being a journal rather than criticism, and be about the way one reads or uses literature, as much as anything else. After all, it is rare ? rare for me ? to read a book from beginning to end in one go. I read, live, return to a book, forget who the characters are (particularly if they have Russian names), pick up another book, put it down, go on holiday and, maybe, get to the end while having forgotten the beginning.

As an adolescent, and in my twenties and thirties, I read consistently and even seriously. By seriously I mean I read stuff I didn?t want to read, even making notes, hoping this would help the material become part of me. I felt I?d had a pretty poor education until the age of sixteen. Or, rather, having read so many public-school novels ? school novels then didn?t seem to be any other kind ? I had intimidating fantasies about those book-stuffed public-school boys, kids like my father, who knew Latin and understood syntax. I was convinced they?d be way ahead of me, intellectually and therefore socially. People would want to hear what they had to say.

What I required from reading was to extend my knowledge and what I thought of as my ?orientation?. This meant having new ideas, which would function like tools or instructions, making me feel less helpless in the world, less bereft, less of a child. If you knew about things in advance, they wouldn?t seem so intimidating, you would be prepared, as though you?d been given a map of the future. My mother and sister mystified me, so I wanted, for instance, to find out about sex, and what women were like, what they felt and thought about, and whether it was different from men, particularly when men were not present. And, when I began writing myself, I wanted to find out what was going on in the literary arena, what other writers were thinking and doing ? how they were symbolising the contemporary world, for instance ? and what I, in turn, might be able to do.

Although I have this idea of myself as not having enough education ? enough for what? ? a couple of years ago my mother found, in the attic of our house in the suburbs where she still lives, a notebook with a home-made cover of wallpaper. I started it in 1964, when I was ten, and listed the books I had read. It must have been around then that I began to write everything down in an ever-increasing number of pompously-named notebooks, as though the world only had reality once it was translated into words. Thinking about this now, I can?t help but find it odd that for me ?education? always meant reading, the accumulation of information. I never thought of it in terms of experience, for instance, or feeling or pleasure or conversation.

In 1964, to my surprise, I read one hundred and twenty-two books. Some Arthur Ransome; more than enough Enid Blyton; E. Nesbit; Mark Twain; Richmal Crompton; oddities like Pakistan Cricket on the March; Adventure Stories for Boys by ?lots and lots of people?; Stalky & Co and The Jungle Book.

Four years later, in 1968, the tone had changed. January begins with Billy Bunter the Hiker but right after it came The Man with the Golden Gun, which is followed by G-Man at the Yard by Peter Cheyney. Then it?s From Russia With Love, The Saint, The Freddie Trueman Story, P. G. Wodehouse, Mickey Spillane and the Beatles biography by Hunter Davies (in brackets, ?re-read?, which is unusual for me at that stage). Finally there is Writing and Selling Fact & Fiction by Harry Edward Neal.

In 1974 I was supposed to be at university, but didn?t feel like attending classes. After all, I?d been at school, sitting still and listening, since I was five. I was, in fact, writing and living with my girlfriend in Morecambe, Lancashire, a run-down freezing seaside town not far from the Heysham Head nuclear power station. It was the first time I?d lived with anyone not my parents. Once we hitch-hiked to the Lake District, otherwise we?d walk on the cliffs and the sand, and listen to music. Sometimes we would cook and eat huge meals, consisting of five or six courses, eating until we were stuffed, until we couldn?t move, and passed out where we lay.

Morecambe was far from London. That was the idea. Except that you leave home and recreate your home life in another place, where the regime you make is even more fervent, the obedience greater. I was, therefore, mostly behind a closed door, having written in my diary, in 1970, ?The idea is for me to stay in my room all the time.? This was my father?s wish for me ? one he made when he thought I should become a writer ? and it was already the only place I felt safe, something I would feel for years, and still do, to a certain extent. Perhaps my girlfriend made me embarrassed about the writing-things-down habit, as well as the lists, notebooks and much else. (I still do the lists, but about other things.) The books read during this time are by Sartre and Camus, Alan Watts and Beckett, before the lists stop. Maybe, for a bit, I went out into the world. The last entry is Fitzgerald?s The Beautiful and Damned, of which I recall almost nothing, only the memorable image of a weeping woman on a bed, halfmad, embracing a shoe. I liked anything erotic, of course. Not that there had been much around. Lady Chatterley, Lolita and even The Catcher in the Rye ? then considered to be a ?dirty? book ? were kept in dad?s bedroom. None of them did much for me. James Bond was better; Harold Robbins represented a delicious, shameless indulgence. My girlfriend, who was a good teacher, introduced me to the work of Philip Roth and Erica Jong, as well as to that of Miles Davis and Mahler.

But these are other artists and I am vacillating. Pressingly, there is still the question of the semihidden book in the folder poking out from under a pile of other papers in my study, papers I have yet to find a place for, which reproach me every time I spot them. I have to say that I know the folder contains a novel called ?An Indian Adolescence?. My father, who was a civil servant in the Pakistan Embassy in London, wrote novels, stories, and stage and radio plays all his adult life. I think he completed at least four novels, though all were turned down by numerous publishers and agents, which was traumatic for our family, who took the rejection personally. But dad did publish journalism about Pakistan, and about squash and cricket, and wrote two books on Pakistan for young people.

I am sure that ?An Indian Adolescence? was his last novel, written, I guess, after his heart surgery, a bypass, when he was no longer employed in the Embassy, where he?d worked most of his adult life. I have little idea what to expect from dad?s novel, but I do anticipate being shocked and, probab...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFaber & Faber

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0571224032

- ISBN 13 9780571224036

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages198

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

My Ear at His Heart

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 5AUZZZ000GYY_ns

My Ear at His Heart

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ009XWQ_ns

My Ear at His Heart

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks182569