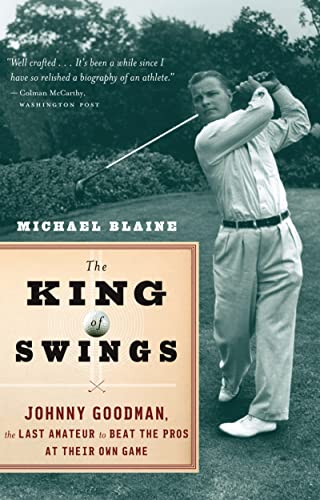

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game - Softcover

Amateur at a little-known California course called Pebble Beach. Goodman’s victory sent shock waves through the rarified world of golf in the Roaring Twenties, but he was just getting started. The idealistic Goodman clung to his amateur status despite lucrative offers from sponsors and Hollywood, ultimately winning the 1933 U.S. Open—the last amateur to perform this stunning feat. A hero in the Depression-era press, Goodman went on to win the 1937 U.S. Amateur—becoming only the fifth golfer in history to wear both crowns.

Like The Greatest Game Ever Played, Michael Blaine’s King of Swings brings the story of one of golf’s forgotten heroes to life.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The fifth child of William and Rose Goodman, Johnny Goodman was born in South Omaha, Nebraska, on December 28, 1909. For most of his childhood he lived in a single-story frame house at 4128 South Thirty-sixth Street, in close proximity to Omaha’s great stockyards and meatpacking plants.

Johnny Goodman’s name first appeared in the Omaha papers in 1916, when he contracted diphtheria. Alerted to the situation by neighbors, health workers discovered the feverish boy in a bed he shared with three other siblings. In the same room, four more Goodman children slept in a single bed. Suspicious of the officials’ motives and fearful of hospitals in general, Rose Goodman refused to allow the authorities to take her son away for treatment. In response to her intransigence, the city quarantined the entire family.

Today, Rose’s resistance to medical intervention would be viewed as irrational, bordering on child abuse. But for an illiterate immigrant whose knowledge of hospitals was limited to the unsanitary poor wards of Lithuania, her actions can be seen in a different light.

However misguided, she was taking a stand to protect her son. Miraculously, none of Rose’s other children caught the disease and Johnny eventually recovered.

Johnny’s father worked in one of the city’s meatpacking plants. Every morning William Goodman would join the masses of men and animals pouring toward the looming slaughterhouses, never knowing if there would be work that day. Over the years he labored in the pickling room, where meat was hauled out of vats of salty water, and the boning room, where the air contained fine bits of bone that lodged in workers’ lungs. If he was lucky he’d catch on with the hog-killing gang a man could breathe better on that job but there were always accidents. If you got cut, you wrapped a rag around the wound and kept on slicing.

He stood all day long in blood and water up to his ankles. On the killing floor in the winter his feet would grow numb with cold, and he would wrap them in layer after layer of cloth until he felt as if he were walking on frozen hooves, but he was thankful for the job; back in Lithuania, there was little work for a man like him. Eventually he became a butcher and earned a little more an hour. It was a dangerous job during speedups” on the line the exhausted men sometimes cut one another accidentally with razor-sharp knives but you stuck some plaster on the wound, you laughed it off, and cut some more.

He worked hard and provided for his wife and children. In fact, he managed to buy his own home. By then he had nine children, all of whom attended school. He made his mortgage payments and fed his family.

Despite his punishing job, William learned to read and write English. For a number of years he was the picture of an upwardly mobile man, able to feed and clothe his sprawling family. But hacking away at steer carcasses ten hours a day left him worn out and hungry for release. At the end of his shift he began joining the other meatpackers in the local saloons. At first it was just for the free pea soup and boiled cabbage, for the raw talk about who almost fell into which vat, who skinned himself good, and what the bosses were going to pull next. There was nothing unusual about downing a few beers after a hard day’s work, but William Goodman’s taste for liquor grew, and soon he was staying out later and later.

There were joints that would serve you after hours too, and if you didn’t get home in time to sleep, you could still make the next shift. If you were a minute late, the company docked you an hour’s pay.

And if you didn’t get home on payday, you could always show up the next day as long as you had a few dollars to throw down on the kitchen table.

Johnny learned to stay out of his father’s way on the nights he came roaring home. He learned the telltale sounds that meant trouble, the scraping of a key that missed the lock, the low muttering, the uneven shuffle of uncertain feet, and he learned to make himself small. Sometimes Anna and Mary and Johnny would skitter out to the yard and wait for things to quiet down. It was better to stand outside in the cold than to catch the back of his father’s hand, but then the neighbors might see you and guess what was going on. The thought of strangers looking down on his family made him squirm.

More often than not, he prayed his father would never come home. At the same time, he wished he would come home, but sober and quiet. In the perfectly still mornings after one of his old man’s sprees, his mother never said a word. Johnny learned it was better not to talk about these things. He would gather his books, tiptoe over the wreckage, and make his way out to the street.

In school, the desks were lined up in strict order. The walls were whitewashed and the floors smelled of fresh wax. Subjects cammmmme one after the other at the same time every day. No matter what was happening at home, Johnny got his homework in, and his teachers praised his precise, perfectly slanted handwriting. When complimented, he would look at his shoes he never said much when teachers praised him but he liked the kind words more than he’d admit.

His father couldn’t touch him in school. He didn’t even know that Johnny was doing better than his brothers and sisters had ever done, and he probably wouldn’t have cared. But in school Johnny felt as good as the next kid, and sometimes better.

William Goodman maintained an ominous silence when he wasn’t drunk. He brooded or slept half the day. Then he was gone again. Over time, his absences grew longer. He would disappear for weeks at a time, then turn up at the table for a bowl of mushroom barley soup with bacon and carrot baba, a queer dish that Johnny’s mother insisted on making even though the kids thought it tasted strange, foreign. Maybe she thought good Lithuanian cooking would keep her husband coming back.

Other fathers Johnny knew went on binges, too. Other fathers sat in the corner of overheated kitchens and never said a word. At least on the surface, the Goodmans weren’t all that different from the other immigrant families who lived cheek by jowl in his neighborhood. You just kept your mouth shut about the bad times, and you didn’t stick your nose into other people’s business.

On a warm June day when he was eleven years old, Johnny went wandering down the tracks and clear out of South Omaha. He was accompanied by his younger friend, Matt Zadalis. The boys passed out of the confines of the stockyards and slaughterhouses into the more genteel precincts of the Omaha Field Club. The golf course’s rolling hills framed the roadbed, but they had only the haziest idea of what the men and women waving clubs were doing.

At four separate points, golfers had to cross the railroad tracks, but when Johnny and Matt saw a foursome sauntering across the roadbed, they didn’t think much of it. For all they knew, every golf course in the world was split by a set of rails.

Then they saw the ball nestled outside the fence, right between the tracks. Johnny picked the thing up and brushed off the grit. It was smaller than a baseball, and it didn’t have any stitching on its strangely slick surface. What was it made of?

On schedule, a steam locomotive whistled. Before they even saw the train, the boys could feel the tracks vibrating. They weren’t frightened. They had half a minute to hop out of the way. Every kind of car flashed by. Boxcars, cattle cars, flatbeds, a dusty tanker.

Johnny flipped the ball a second time. There was something appealing about it, but he couldn’t explain it. He wondered how high it would bounce.

Then a man appeared on the other side of the fence. He was wearing pants bunched below his knees. Knickers, they called them. Approaching, he offered an easy smile, but the boys were wary.

The closer the golfer came to the fence, the more the boys pulled away. They were suspicious. Adults were always telling you what to do.

Then the man made a proposal. He would give them a nickel in return for the ball. It sounded like a good deal, but the boys still had doubts. Maybe the man was trying to trick them into doing some chores. On the other hand, maybe he was on the level. Johnny wanted to see Shark Monroe, starring the movie cowboy William S. Hart. The four-reeler was playing downtown. Movies cost money.

To be safe, Johnny stepped back from the fence and made the man repeat the offer.

Finally, with an easy motion, Johnny tossed the ball over the fence. A moment later the coin came sailing down. Johnny snatched it out of the air.

Then the man told them something even more intriguing. For carrying a player’s golf bag around the field, they could make fifty cents. The man called the job caddying.

You had to be eleven. Johnny was old enough, and Matt swore he was, too. Johnny could imagine his mother’s face if he came home with fifty cents.

In a few days Johnny and Matt were looping at the Omaha Field Club. At first it wasn’t easy. Johnny had to ask the other boys what to do, and more often than not they hooted at his ignorance. Once in a while, in a voice barely above a whisper, he questioned the stern caddiemaster about the names of the clubs. They all sounded funny. Niblick, mashie, spade mashie, midiron, brassie, spoon, driver, putter. Didn’t you dig with a spade? Didn’t cars putter?

He watched the players to see how high and far the balls hit with each club went, and how high and far each member could hit each specific club. By observing the other bag haulers, he learned where to stand close enough to dispense the right club but far enough away to keep from catching the eye of a golfer in deep concentration over his ball.

During the first few weeks, he wondered if he would ever get the names of the clubs and the arcane rules straight in his head. Early on in Johnny’s caddying education, one old man snarled at him for stepping on his line on the second green. What was a line? Johnny stared and stared at the green, unable to make the damn thing out. When the round ended, the old buzzard stiffed Johnny without a word. Johnny would have to find out what a line was or work for nothing.

The caddies called the cheap members snakes and the generous ones snags. A snake would always find fault; a snag would be free with his money even if you made one or two mistakes. Johnny learned to make himself scarce when a snake was looking for a caddie.

Every Sunday Johnny hauled bags around the carefully tended Field Club layout twice, but sometimes he showed up late because his mother made him attend Mass. He was a bright, eager boy, though, so the members didn’t make a fuss. More often than not, caddies were devoted to worse pursuits.

Johnny and Matt didn’t forget the five cents they made on the man’s golf ball, either. Hunting lost balls became a fever. They found them in clumps of grass on the edges of railroad ties. They found them under scraggly bushes near the country club. They found them sunk in mud puddles and once in a while just sitting out there in plain sight like dimpled eggs. If one ball was worth a nickel, how much would ten, twenty, thirty get them? After three weeks, Johnny and Matt built up a huge hoard, one hundred balls on the nose.

They carried them in a gunnysack to the caddiemaster, who sent them to the pro, an avuncular man in tweeds who hoisted the bag of balls and tossed it behind the counter. They waited eagerly for the money to pour from his pocket, but instead he pulled a battered mashie a five iron out of a barrel.

The boys didn’t know what to make of the thing, but they were sure they’d been cheated. The club had a scarred hickory shaft, and the clubface was studded with a pattern of small holes the reason, they figured, that the man was throwing it away. In a shy voice, Johnny spoke up. Couldn’t they get some money for the balls instead?

The caddiemaster gave them a severe look. Hadn’t he given them a good golf club? What more did they want?

Disappointed, they retreated with their dubious prize in hand. Matt had secreted one cut ball in the pocket of his short pants. When they passed through the club’s gates, he tossed it into the air.

The boys exchanged glances. There was a farm a couple of miles away. They’d be safer hitting the ball there. The cows wouldn’t mind. Nervous excitement ran through the boys now. Maybe it hadn’t been such a bad deal.

They slid under the farmer’s fence and placed the ball on a tuft of grass. Johnny splayed his feet the way the toffs at the club did, but there was something wrong. The clubface was turned backward. The pro had slipped them damaged goods. Johnny took a mighty swing, but the ball dribbled away, never leaving the ground.

In silence the boys examined the mashie, turning it this way and that. Then Johnny had an idea. If the clubhead was screwed on backward, then he’d line up backward too. He reversed the position of his hands, placing the left below the right, and set himself up on the other side of the ball.

Now the clubface was aimed in the right direction. Could he swing left-handed, though? Why not? He knew a kid who threw righty and batted lefty. Johnny took a long backswing, swayed back, got up on his toes, and whaled one. Veering left in a screaming slice, the ball barely rose ten feet, but it did get up in the air. Now he was running after it, Matt whooping at his heels.

Soon they developed their own game. Whoever hit the ball farthest in an afternoon got to take the club home and practice with it. Years later spectators marveled when, blocked against a tree, Johnny Goodman would make a miraculous left-handed recovery, but Matt Zadalis knew how long Johnny had labored to perfect that swing.

Copyright © 2006 by Michael Blaine. Reprinted with permission by Houghton Mifflin Company.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMariner Books

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0618871896

- ISBN 13 9780618871896

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0618871896-2-1

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0618871896-new

King of Swings : Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 4981583-n

The King of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. The King of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game 0.85. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780618871896

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2416190080423

The King Of Swings Pa by Blaine, Michael [Paperback ]

Print on DemandBook Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. This item is printed on demand. Seller Inventory # 9780618871896

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0618871896

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0618871896

The King Of Swings: Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0618871896

The King of Swings Johnny Goodman, the Last Amateur to Beat the Pros at Their Own Game

Print on DemandBook Description PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. THIS BOOK IS PRINTED ON DEMAND. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # IQ-9780618871896