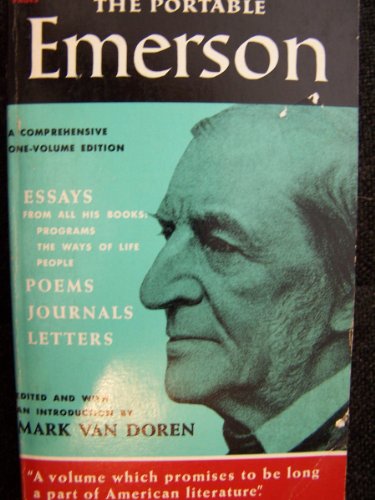

The Portable Emerson - Softcover

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s diverse body of work has done more than perhaps any other thinker to shape and define the American mind. Literary giants including Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Walt Whitman were among Emerson’s admirers and protégés, while his central text, Nature, singlehandedly engendered an entire spiritual and intellectual movement in transcendentalism. This long-awaited update—the first in more than thirty years—presents the core of Emerson’s writings, including Nature and The American Scholar, along with revelatory journal entries, letters, poetry, and a sermon.

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,700 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Jeffrey S. Cramer is the Curator of Collections at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods. He is the editor of the award-winning Walden: A Fully Annotated Edition, The Quotable Thoreau, among other books. He lives in Maynard, Massachusetts.

—EMERSON, IN HIS JOURNAL, 1828

Acknowledgments

To my editor at Penguin, Elda Rotor, for seeing the need for a new edition of The Portable Emerson, first edited by Mark Van Doren in 1946 and reedited by Carl Bode in 1977.

To the Ralph Waldo Emerson Memorial Association for permission to include the selection from Emerson’s correspondence.

And to my family—Julia, Kazia, and Zoë—for sharing our home with yet another Transcendentalist.

Introduction

To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men,—that is genius.

—EMERSON IN “SELF-RELIANCE”1

“I often say of Emerson,” Walt Whitman eulogized half-a-dozen years after Emerson’s death,

that the personality of the man—the wonderful heart and soul of the man, present in all he writes, thinks, does, hopes—goes far towards justifying the whole literary business—the whole raft good and bad, the entire system. You see, I find nothing in literature that is valuable simply for its professional quality: literature is only valuable in the measure of the passion—the blood and muscle—with which it is invested—which lies concealed and active in it.2

Emerson would agree. As he wrote in his journal of 1845, “Writing should be the settlement of dew on the leaf, of stalactites on the wall of the grotto, the deposit of flesh from the blood, of woody fibre in the tree from the sap.”3 It was not only that the words need to be created from an author’s lifeblood, however, but that it must produce a correspondent passion in the reader: “Let us answer a book of ink with a book of flesh and blood.”4 The right use of books, the “one end which all means go to effect,” he wrote, is “for nothing but to inspire. I had better never see a book than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul.”5

Like Henry David Thoreau, who, in Walden, wanted to wake his neighbors up, Emerson said of his neighbors while in the midst of writing his first book, Nature: “They want awakening. Get the soul out of bed, out of her deep habitual sleep, out into God’s universe, to a perception of its beauty, and hearing of its call, and your vulgar man, your prosy, selfish sensualist awakes, a god, and is conscious of force to shake the world.”6

Emerson did not want a generation of disciples, of followers, but of original thinkers. “I have been writing and speaking what were once called novelties, for twenty-five or thirty years, and have not now one disciple. Why?” Emerson asked in 1859:

Not that what I said was not true; not that it has not found intelligent receivers but because it did not go from any wish in me to bring men to me, but to themselves. I delight in driving them from me. What could I do, if they came to me?—they would interrupt and encumber me. This is my boast that I have no school & no follower. I should account it a measure of the impurity of insight, if it did not create independence.7

Those thought of as disciples, such as Thoreau or Margaret Fuller or Amos Bronson Alcott, were appreciated by Emerson for their originality and perception, their ability to “alter my state of mind,”8 and because he found in them “souls that made our souls wiser.”9

• • •

Between May 25, 1803, when he was born without ceremony in the First Church parsonage in Boston to Reverend William and Ruth Haskins Emerson, and April 27, 1882, when the bell of the First Parish in Concord tolled seventy-nine times announcing his death from pneumonia, Ralph Waldo Emerson had become one of America’s leading intellectuals, earning him the epithet, the Sage of Concord. “Great geniuses have the shortest biographies,” Emerson wrote. “Their cousins can tell you nothing about them. They lived in their writings, and so their house and street life was trivial and commonplace.”10

Many who achieve prominence show no particular marks of distinction and promise in their early years. Emerson was no exception. He attended Boston Latin School and Harvard College as a satisfactory student, teaching after graduation in various schools until he decided to prepare for the ministry by attending the Harvard Divinity School. Once licensed to preach he found himself welcome at many pulpits around Boston; he finally accepted a position as colleague, or junior, pastor—soon promoted to pastor—at the Second Church in Boston.

In December 1827 Emerson met Ellen Louisa Tucker. She was sixteen, with a sweet and kind disposition, and tubercular, a condition they either ignored or hoped she would overcome. They married in 1829. Sixteen months later Emerson was a widower. Emerson’s aunt, Mary Moody Emerson, wrote shortly before Ellen’s death, “Waldo has borne so well his personal trials—has done & labored so much for his family that it is grievous to find him so tried—he is discouraged about this lovely flower who has so captivated his affections.”11

After Ellen’s death, Emerson found himself in conflict with the Second Church over the administration of the sacrament, a ritual from which he believed “the life and suitableness have departed,” making it “as worthless . . . as the dead leaves that are falling around us.”12 He had begun his lifelong process of thought, consideration, evaluation, and realignment, in a cycle that left no concept secure, and damned “foolish consistency” as the “hobgoblin of little minds.”13 As he would write in his essay “Circles,” “No truth so sublime but it may be trivial to-morrow in the light of new thoughts.”14

“The true preacher,” Emerson wrote, “can be known by this, that he deals out to the people his life,—life passed through the fire of thought.”15 To be a true preacher for Emerson left him no recourse but to resign his pastorate. Freedom was the “essence”16 of faith. A few days after leaving the Second Church in December 1831 he sailed for Europe, visiting the great sites of Italy and France, but it was in England and Scotland where, having met William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and a man who would be a lifelong friend, Thomas Carlyle, his world changed. Although he did not yet know in what way, the life he left behind in America was not the life he was returning to.

His journal during his European period shows a mind receptive to, sparked and animated by, all his experiences: places he visited, things he saw, events he witnessed, and people he met, all offering new perspectives. When visiting the Jardin des Plantes in Paris he wrote in a notebook that he was

impressed with the inexhaustible riches of nature. The universe is a more amazing puzzle than ever, as you glance along this bewildering series of animated forms—the hazy butterflies, the carved shells, the birds, beasts, fishes, insects, snakes, and the upheaving principle of life everywhere so incipient, in the very rock aping organized forms. Not a form so grotesque, so savage, nor so beautiful but is an expression of some property inherent in man the observer—an occult relation between the very scorpions and man. I feel the centipede in me—cayman, carp, eagle, and fox. I am moved by strange sympathies; I say continually, “I will be a naturalist.”17

His experiences in Paris informed Emerson’s lecture, “The Uses of Natural History,” in which he explained natural history as a lexicon of the language of God and the universe:

Every fact that is disclosed to us in natural history removes one scale more from the eye; makes the face of nature around us so much more significant. . . . Thus knowledge will make the face of the earth significant for us: it will make the stone speak and clothe with grace the meanest weed. Indeed it is worth considering in all animated nature what different aspects the same object presents to the ignorant and the instructed eye. . . . It is in my judgment the greatest office of natural science, and one which as yet is only begun to be discharged, to explain man to himself. . . . The knowledge of all the facts of all the laws of nature will give man his true place in the system of being. . . . Nature is a language and every new fact we learn is a new word. . . . I wish to learn this language—not that I may know a new grammar but that I may read the great book which is written in that tongue.18

Although Emerson continued to preach sermons throughout the 1830s, the number of moralistically religious addresses tapered off rapidly toward the end of the decade as he delivered more discourses and lectures on diverse themes that might attract a wider audience. His interest in science and nature had been expanding since the 1830s. By the 1840s he was speaking increasingly on such issues as abolitionism, Indian rights, America’s focus on materialism, and society’s increasing lack of spiritual support and focus. For Emerson, though, there may have been little difference between the church and the lyceum. As Elizabeth Peabody wrote:

I think Mr. Emerson was always pre-eminently the preacher to his own generation and future ones, but as much—if not more—out of the pulpit as in it; faithful unto the end to his early chosen profession and the vows of his youth. Whether he spoke in the pulpit or lyceum chair, or to friends in his hospitable parlor, or tête-à-tête in his study, or in his favorite walks in the woods with chosen companions, or at the festive gatherings of scholars, or in the conventions of philanthropists, or in the popular assemblies of patriots in times and on occasions that try men’s souls, always and everywhere it was his conscious purpose to utter a “Thus saith the Lord.”19

In 1837 Emerson delivered “The American Scholar” before the Phi Beta Kappa Society in Cambridge. It was an attack on our dependence on the past and a call to arms for a new generation of self-trusting scholars:

Young men of the fairest promise, who begin life upon our shores, inflated by the mountain winds, shined upon by all the stars of God, find the earth below not in unison with these,—but are hindered from action by the disgust which the principles on which business is managed inspire, and turn drudges, or die of disgust. . . . They did not yet see, and thousands of young men as hopeful now crowding to the barriers for the career, do not yet see, that, if the single man plant himself indomitably on his instincts, and there abide, the huge world will come round to him. Patience,—patience;—with the shades of all the good and great for company; and for solace, the perspective of your own infinite life; and for work, the study and the communication of principles, the making those instincts prevalent, the conversion of the world. Is it not the chief disgrace in the world . . . not to yield that peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear? . . . We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds.20

Oliver Wendell Holmes, who was in attendance for this “grand Oration,” called it “our intellectual Declaration of Independence” and witnessed young men leaving the hall as if a prophet had spoken to them.21

Emerson was a writer and lecturer of note, an orator who could inspire and change opinions, but he could also instigate controversy, in particular with his “An Address to the Senior Class in Divinity College, Cambridge,” the following year. Created from his decade-long interest in the German higher criticism that treated the Bible as a group of literary texts deserving critical study of their origins and analysis of their literary history rather than as revealed or inspired texts deserving blind faith, as well as from Emerson’s strong belief in the divinity within, his address should have surprised no one. Nonetheless, it was branded as “the latest form of infidelity”22 by one of the leading Unitarians, Andrews Norton, and Emerson would not be invited back to speak at Harvard for nearly three decades.

Whether a prophet or an infidel, Emerson was in demand as a lecturer, and his lecture tours supplemented the monies he received from his first wife’s estate. In early 1834, while preaching in Plymouth, Emerson met Lydia Jackson, who would be called Lidian, and sometimes Queenie or Asia, by her future husband. They married the following year, lived at Bush, Emerson’s new home in Concord, and raised four children—two sons, two daughters—although their first, Waldo, died from scarlatina at the age of five. Theirs was a love of “sober joy,”23 which contrasted deeply with the youthful and passionate love Emerson had had for Ellen, whose memory lived on with them indelibly at Bush when their first daughter was named for her.

• • •

Just as Thoreau remarked that he lived in “two worlds—the post-office & Nature,”24 and that it was the juxtaposition of these two worlds that created the sphere in which he lived, Emerson was aware that it was the pull of two worlds and the struggle of balancing them both—“angelic insight alternating with bestial activity: sage and tiger”25—that made a whole. It lay him open to charges of inconsistency or insincerity with which he wrestled but ultimately accepted.

I am nominally a believer: yet I hold on to property: I eat my bread with unbelief. I approve every wild action of the experimenters. I say what they say concerning celibacy or money or community of goods and my only apology for not doing their work is preoccupation of mind. I have a work of my own which I know I can do with some success. It would leave that undone if I should undertake with them and I do not see in myself any vigour equal to such an enterprise. My Genius loudly calls me to stay where I am, even with the degradation of owning bank-stock and seeing poor men suffer whilst the Universal Genius apprises me of this disgrace & beckons me to the martyr’s and redeemer’s office.26

As both society and nature made a complete universe, and not one against the other but one in conjunction with the other, so, too, Emerson was aware that there were different plains for the intellect to travel, but that it was the “binding old and new to some purpose”27 that created something unlimited and enduring.

• • •

In 1836 a group of original thinkers was drawn together by the affinity of their ideas. Their meetings were nicknamed the Transcendental Club by their critics. They thought of themselves simply as like-minded.

Transcendentalism was a literary and reform movement that was not a movement, a religion that was not a religion, a circle that had no center and no circumference. It is due to this lack of consensus as to what it is that makes it both difficult and simple to define. Although Emerson said that the “field cannot be well seen from within the field,”28 it still may be the best perspective from which to look at what Transcendentalism was. On December 23, 1841, Emerson read a lecture on it, “The Transcendentalist,” at the Masonic Temple in Boston. It began:

The first thing we have to say respecting what are called new views here in New England, at the present time, is, that they are not new, but the very oldest of thoughts cast into the mold of these new times. . . . What is popularly called Transcendentalism among us, is Idealism; Idealism as it appears in 1842. As thinkers, mankind have ever divided into two sects, Materialists and Idealists; the first class founding on experience, the second on consciousness; the first class beginning to think from the data of the s...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherViking Adult

- Publication date1946

- ISBN 10 0670010251

- ISBN 13 9780670010257

- BindingPaperback

- EditorVan Doren Mark

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Portable Emerson

Book Description Condition: Good. SHIPS FROM USA. Used books have different signs of use and do not include supplemental materials such as CDs, Dvds, Access Codes, charts or any other extra material. All used books might have various degrees of writing, highliting and wear and tear and possibly be an ex-library with the usual stickers and stamps. Dust Jackets are not guaranteed and when still present, they will have various degrees of tear and damage. All images are Stock Photos, not of the actual item. book. Seller Inventory # 9-0670010251-G

Emerson

Book Description Condition: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 10429166-6