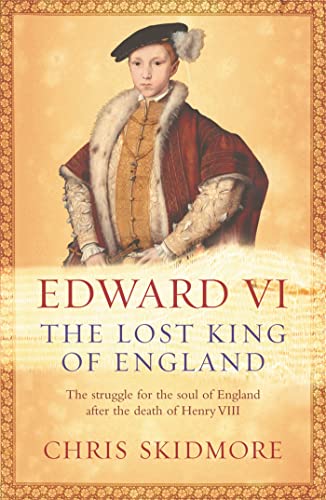

Edward VI: The Lost King of England - Softcover

In his desperate quest for an heir, King Henry VIII divorced one wife and beheaded another. The birth of Prince Edward on October 12, 1537, ended his father's twenty-seven-year wait. Nine years later, Edward was on the throne, a boy-king of a nation in religious limbo and in a court where manipulation, treachery, and plotting were rife.

Chris Skidmore describes how, in the six years of Edward's reign, court intrigue, deceit, and treason very nearly plunged the country into civil war while the stability that the Tudors had sought to achieve came close to being torn apart. Even today, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I are considered the two dominant figures of the Tudor period. But Edward's reign is equally important. It was one of dramatic change and tumult whose impact is still felt today―certainly in terms of his religious reformation, which not only exceeded Henry's ambitions but has endured for over four centuries since Edward's death in 1553.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Chris Skidmore was born in Bristol, England, in 1981. He is a prize-winning honors graduate of Oxford University and is adviser to the British Shadow Secretary for Education.

Henry VIII never underestimated the importance of a male heir. It was a lesson he had learnt at an early age. The turn of Fortune's wheel could be cruel, as it had been when he was just ten years old. Then the sudden death of his elder brother Arthur in April 1502 propelled him into the limelight as heir to the throne; overnight, Henry's life changed drastically. He was never meant to be king, nor had he even been prepared for such a task. For the sensitive and mild-mannered young child, a career in the Church had possibly beckoned; now, as Prince of Wales and sole male heir of the Tudor dynasty, he was kept so closely guarded that a Spanish envoy remarked how he might have been a girl, locked away in his chamber and only allowed to speak when answering his father.

Arthur's death was a devastating blow for his father, Henry VII. His victory against Richard III at the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 had seemed unequivocal, ending over half a century of civil war between the rival houses of Lancaster and York, later better known as the Wars of the Roses. Yet new claimants to the throne had sprung up, challenging his legitimacy to rule. For the next fifteen years, Henry battled for his new dynasty to be recognized by the ruling empires of Europe, marrying his eldest son Arthur off to Katherine of Aragon, the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, the rulers of Spain. Nevertheless, Henry had always struggled to fit in amongst his own subjects and in particular his nobility--the ruling families, around fifty in number, upon whose support the monarch was largely dependent. Raised in Brittany and France, Henry was an outsider who brought with him a new style of government from overseas, scrutinizing every payment issued from his chamber with his own hand. For all it was worth, Henry's penny-pinching ways earned him little respect and fewer friends.

With only one male heir to fall back on--and a child at that--Henry knew that the Tudor name was seriously under threat. Yet worse still was to come the following year, when his wife Queen Elizabeth died in childbirth, attempting to deliver him another precious son. The Tudor dynasty hung dangerously by the thread of his son's life: with no other male heirs, extinction of the royal line loomed close.

The effects of all this upon the forming mind of the young Henry VIII cannot possibly be overestimated, for when he came to the throne six years later, aged almost eighteen, he was determined not to make his father's mistakes. In the years leading up to his death, Henry VII had placed his nobility under heavy financial penalties and bonds for the slightest misdemeanour, much to their chagrin. Now, in an inspired move designed to bolster his own reputation, Henry agreed to have his father's chief ministers, Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley, made scapegoats, ordering that they be thrown into the Tower and executed upon dubious charges of treason. Henry came as an immediate breath of fresh air; he soon ingratiated himself with the ruling elite, sharing their passions for hawking and hunting, and recklessly joining them in dangerous jousting competitions--the sight of which would have had his father turning in his grave. But he realized that for his reign to be fully secure and his mind set at rest, a male heir was vital. Fortunately for Henry, his brother's death had resulted in him gaining a wife--Arthur's widow, Katherine of Aragon. As to her womanly duties of providing the realm's heir, she did not disappoint. On New Year's Day 1511, Queen Katherine was delivered of a boy. As the style of his newborn son and heir, also named Henry, was proclaimed, the news was welcomed with bells, bonfires and the endless salute of guns shot from the Tower.

Henry celebrated with a pilgrimage to Walsingham, before returning to Westminster for a tournament and pageant. It was the most splendid of his reign. There he was mobbed by the crowd, who for souvenirs ripped off the golden 'Hs' and 'Ks' sewn on to his doublet. In his joy, Henry did not care. Yet the celebrations proved premature: seven weeks later, the baby was dead.

In February 1516, Katherine was again delivered of a healthy child. This time the baby lived--the only problem being that the child was a girl, Mary. Though naturally disappointed, Henry remained optimistic. 'We are both young,' he told the Venetian ambassador. 'If it was a daughter this time, by the grace of God the sons will follow.' Yet they did not, and his subjects' anxiety over the succession began to reflect Henry's own: 'I pray God heartily to send us a Prince,' one courtier wrote, 'for the surety of this realm.' But it was not to be, for Katherine was destined to fail in her duties. After three miscarriages (two of them male) and two infants who had died within weeks of the birth (one male), by the end of the 1520s Henry had to face up to the inevitable. Katherine was now approaching her forties and surely reaching an age when conception was an unlikely and dangerous possibility--she would have to go. For Henry had a new lover--Katherine's maid-of-honour, Anne Boleyn--who would accept nothing less than to take her mistress's place as queen. Allure had turned to infatuation as Anne promised to provide Henry with the one thing Katherine had not: a son. But once she had replaced Katherine in Henry's affections--though not in his subjects'--she fared little better as queen, and the birth of their daughter Elizabeth, together with two miscarriages, convinced Henry that 'God did not wish to give him male children'.1

Besides, Anne made as many enemies as she had friends. She made the mistake of crossing Thomas Cromwell, Henry's first minister--a mistake for which she would pay heavily. As loyalties divided, splintering the court, with factions competing for the king's favour, it soon became clear to Cromwell that Anne was a more dangerous prospect than he had feared. At first, she had been the reason behind his meteoric rise at court; her thinly veiled hatred of Henry's former favourite, Cardinal Wolsey, allowing Cromwell to take Wolsey's place once he fell from grace. But Cromwell knew if he was to save his own head from eventually reaching the block, he had to seek Anne's first. After her third miscarriage, he engineered a plot to bring down the queen, accusing her of adultery with her musician, Mark Smeaton. Henry believed every charge levelled against Anne: whether there was any truth behind them, Henry probably did not care; he wanted her gone. Eleven days after Anne's execution, he had married once again.

His choice of the plain Jane Seymour as bride was in stark contrast to Anne. 'She is of middle height, and nobody thinks she is of much beauty,' the Imperial ambassador confided.2 Quiet and obedient, she came as a refreshing change: 'She is as gentle a lady as ever I knew,' one courtier wrote. 'The King hath come out of hell into heaven.'3

Jane's motto, 'Bound to obey and serve', reflected her own understanding of what needed to be done. She would be Henry's dutiful wife and subject, yet she aimed not just to be Henry's loyal queen, but to give him exactly what he wanted: a son. It was through her, she intended, that the Tudor dynasty would be reborn. Although in no doubt as to what needed to be achieved, however, Jane struggled to conceive. Henry soon grew restless. His eyes began to wander once more; meeting two young ladies, he admitted with a sigh he was 'sorry that he had not seen them before they were married'.4

Yet in early spring 1537 Jane knew she was pregnant. Shortly afterwards, she travelled with a no doubt overjoyed Henry, making a pilgrimage at Canterbury. Here they gave thanks to God and laid their offerings at the shrine of the English saint Thomas Becket. It was the last time Henry would make such a gesture. As the dissolution of the monasteries continued apace, such devotions were ordered to be abandoned. Within a year Becket's memory would be denounced, his shrine broken up and his bones scattered.

By April Jane's pregnancy was considered advanced enough for the news to be announced at a meeting of the Privy Council, where the need was felt to record their congratulations in the minutes. Soon the good news had spread across the country; in late May it was announced that the child had 'quickened'--kicked--sparking off further cause for celebration. Mass was celebrated in St Paul's with a thanksgiving, and the Te Deum was ordered to be sung in churches across the country. 'God send her good deliverance of a prince,' wrote one courtier expectantly, 'to the joy of all faithful subjects.'5

Henry marked his own expectation of fathering an heir by commissioning the court painter Hans Holbein the Younger to prepare a fresco for the walls of the Privy Chamber, depicting himself, Jane, his father Henry VII and his mother Elizabeth of York. The symbolism was telling, for Henry stands dominant in heroic pose, towering in front of his age-weary father. Beside them a monumental inscription set into a plinth proudly read:

If you rejoice to see the likeness of glorious heroes, look on these, for no painting ever boasted greater. How difficult the debate, the issue, the question whether the father or son be the superior. Each of them has triumphed. The first got the better of his enemies, bore up his so-often ruined land and gave lasting peace to his people. The son, born to still greater things, turned away from the altars of that unworthy man and brings in men of integrity. The presumptuousness of popes has yielded to unerring virtue, and with Henry VIII bearing the sceptre in his hand, religion has been restored, and with him on the throne the truths of God have begun to be held in due reverence.6

On the other side of the monument, it was easy not to notice Jane, both diminutive and submissive. This was hardly surprising, for Henry expected his queen and soon-to-be mother to his heir to act the obedient subject. Jane played the role to perfection. She was, Henry wrote in September 1537, 'of that loving inclination and reverend conformity'. He could not leave her side since Jane, 'being a woman', might take fright in his absence, risking miscarriage.7

With her pregnancy in its final stage, Jane took to her chamber on 16 September. Her confinement lasted three weeks, culminating in a difficult and painful labour lasting over thirty hours.8 Meanwhile the plague had been raging around Hampton Court, and Henry was forced to move to Esher for four days. Everybody waited anxiously 'We look daily for a Prince,' one courtier wrote to another. 'God send what shall please him.' On Thursday 11 October a solemn procession took place at St Paul's to pray for Jane.9

At two o'clock in the morning of St Edward's Day, Friday 12 October, Jane gave birth to a healthy child. By eight o'clock the news had leaked out of the court. It was a son. The church bells of London began a fanatical peal that lasted throughout the day, whilst in celebration the Te Deum was again sung in every parish church. At St Paul's there was a solemn procession. Bonfires were lit in streets; garlands were hung from balconies, whilst fruit and wine were handed out as presents by city merchants. Eager to impress, German merchants at the Steel Yard distributed a hogshead of wine and two barrels of beer to the poor.10 The celebrations continued well into the night as the Lord Mayor rode through the crowds, thanking the people for their rejoicing and calling on them to give thanks to God. To finish, the guards at the Tower of London fired off over two thousand rounds into the night sky.

Messengers were dispatched across the country with letters from the queen proudly announcing the news.11 Jane urged her subjects to give thanks to God, 'but also continually pray for the long continuance and preservation of the same here in this life...and tranquillity of this whole realm'. Indeed, it could be said that the baby's life and the future prospects of the kingdom were one and the same.

Letters were soon shuttling across Europe, their contents running along a similar vein. 'Here be no news,' Thomas Cromwell wrote, 'but very good news...I have received this morning...it hath pleased Almighty God of his goodness, to send unto the Queen's Grace deliverance of a goodly Prince.' The announcement of the birth, another letter read, 'hath more rejoiced this realm and all true hearts...more than anything hath done this 40 years'.12

Henry was at his hunting lodge in Esher when he heard. After the long wait of twenty-seven years, he finally had his heir. No record survives of the moment he first found out the news, though one suspects that musing upon the sacrifices he had made--divorce, Reformation, execution--a sense of vindication pulsed through him. Overcome with joy, he sped back to Hampton Court to choose the baby's name: Edward, after his distant royal ancestor, Edward the Confessor, whose memory happened to be celebrated that day--his saint's day.

Like an over-protective father, Henry took immediate control of the situation, commanding that every room and hall in the nursery recently built for the prince be swept and soaped down, ready for its royal occupant. The baby was then taken from Jane's arms and placed in the care of a wet nurse and other nursemaids; Jane did not make a fuss about suckling her child--for now she took her rest after an exhausting labour.

On Monday 15 October, Edward was christened in the royal chapel at Hampton Court. Preparations had begun almost immediately after the baby was born, but now Henry began to grow nervous for the child's safety. The plague had been rife in areas outside London for the past few months, centred about Croydon. Now a proclamation was hastily dispatched forbidding anyone residing in affected areas to come to court at all. This would mean that the king's own niece, Gertrude Courtenay, the Marchioness of Exeter, who had been appointed to carry the prince himself, would have been barred from the ceremony, had it not been for her own pleading.

Writing to Henry the day before, she waxed on unashamedly: Edward's birth was 'the most joyful news, and glad tidings, that came to England these many years; for which we, all your Grace's poor subjects are most bounden to give thanks to Almighty God that it hath pleased him of his great mercy so to remember Your Grace with a Prince, and us all, your poor subjects, to the great comfort, universal weal, and quietness of this your whole realm; beseeching Almighty God to send His Grace life and long...' And so it continues, Gertrude giving her thanks to Henry, 'as my poor heart can think', for granting her the honour of carrying Edward during the ceremony, she being 'so poor a woman to so high a room': 'Which service...I should have been as glad to have done as any poor woman living. And much it grieveth me, that my fortune is so evil, by reason of sickness here, in Croydon, to be banished.'13

As Gertrude well knew, with Henry flattery got you everywhere; needless to say, she got her way. Henry had made a rare exception, but the nobility scattered across the country on their estates had already taken to their saddles to arrive at the most eagerly expected event of the decade, to glimpse a sight of the new heir to the throne. Their retinues were ordered to be scaled down to reduce the risk of infection: dukes, usually accustomed to travelling with their entourage numbering into hundreds, were allowed no more than six gentlemen, marquesses no more than five. Nevertheless, the audience that gathered in the state rooms that led from the bedchamber to the Royal Chapel was still expected to number around four hundred.

The ceremonies for the christening followed the carefully planned ordinances set down by Henry's grandmother, Lady Margar...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPhoenix

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0753823519

- ISBN 13 9780753823514

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Edward VI (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. The sole surviving male heir of Henry VIII, Edward VI was only nine years old when he came to the throne in 1547. Reigning for just six years, Edward was surrounded by the manipulation and plotting rife in the Tudor court even before his father's death.Power struggles between his uncles were just one indication of the turbulent and treacherous climate surrounding him. But changes wrought in Edward's short reign make him a central figure in the Tudor age.His own journals and letters offer a compelling picture not only of Edward's personal and political life - a life of great promise, tragically cut short - but of the fascinating court in which he lived. The struggle for the soul of England after the death of Henry VIII Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9780753823514

Edward VI

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Language: ENG. Seller Inventory # 9780753823514

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Paperback / softback. Condition: New. New copy - Usually dispatched within 4 working days. The struggle for the soul of England after the death of Henry VIII. Seller Inventory # B9780753823514

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 915a3d9bf69823f2741c1f8bf9067fd4

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. BRAND NEW ** SUPER FAST SHIPPING FROM UK WAREHOUSE ** 30 DAY MONEY BACK GUARANTEE. Seller Inventory # 9780753823514-GDR

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 368 pages. 7.76x5.12x1.06 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # __0753823519

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Condition: New. 2008. Paperback. The struggle for the soul of England after the death of Henry VIII Num Pages: 368 pages, Illustrations (some col.), maps. BIC Classification: 1DBKE; 3JB; BGR; HBJD1; HBLH. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 196 x 131 x 28. Weight in Grams: 302. . . . . . Seller Inventory # V9780753823514

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Condition: New. In. Seller Inventory # ria9780753823514_new

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Condition: New. 2008. Paperback. The struggle for the soul of England after the death of Henry VIII Num Pages: 368 pages, Illustrations (some col.), maps. BIC Classification: 1DBKE; 3JB; BGR; HBJD1; HBLH. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 196 x 131 x 28. Weight in Grams: 302. . . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Seller Inventory # V9780753823514

Edward VI: The Lost King of England

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 6666-GRD-9780753823514